| In Memoriam: Professor Sydney Anglo  It is with considerable lament that I regretfully write of the passing of Sydney Anglo. He was 93 and his passing on October 14th of old age was quiet in his home in Brighton, East Sussex. He is survived by a nephew and niece. Sydney was a tremendous force in the revival of forgotten European martial art studies and was instrumental in making them a serious academic subject. There is no one who made a greater impact in bringing our subject to the forefront as a legitimate and respectable field of research. There’s no denying his work has proven the most significant for our subject since the 19th century. Through his discoveries and writings, Sydney was an early guide in the revival of European martial arts studies and instrumental in establishing them as an important area of historical research as well as placing them among the humanities. We were fortunate to be to have long had him as the ARMA’s academic advisor. No one studying  our craft today can deny the monumental importance of his work. His seminal achievement was 2000’s, The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe,

the virtual Bible of our subject that remains mandatory reading (and

re-reading). It was the first major study of its kind in over 100 years

and introduced an entire generation, if not the world, to an entirely

new understanding of martial art traditions and fencing history. Its

depth and breadth of material combined with a loving respect for its

topic set the path for every student of Medieval and Renaissance

close-combat studies to follow. His uncovering of major martial texts

and masters such as, Le Jeu de la Hache,

Frederico Ghisliero, Don Pedro de Heredia, as well as bringing new

perspective to works such as Heemserck, Lovino, Cavendish, and

Wallhausen among others, along with his research into the

under-appreciated R.L. Scott collection, forever changed our craft. our craft today can deny the monumental importance of his work. His seminal achievement was 2000’s, The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe,

the virtual Bible of our subject that remains mandatory reading (and

re-reading). It was the first major study of its kind in over 100 years

and introduced an entire generation, if not the world, to an entirely

new understanding of martial art traditions and fencing history. Its

depth and breadth of material combined with a loving respect for its

topic set the path for every student of Medieval and Renaissance

close-combat studies to follow. His uncovering of major martial texts

and masters such as, Le Jeu de la Hache,

Frederico Ghisliero, Don Pedro de Heredia, as well as bringing new

perspective to works such as Heemserck, Lovino, Cavendish, and

Wallhausen among others, along with his research into the

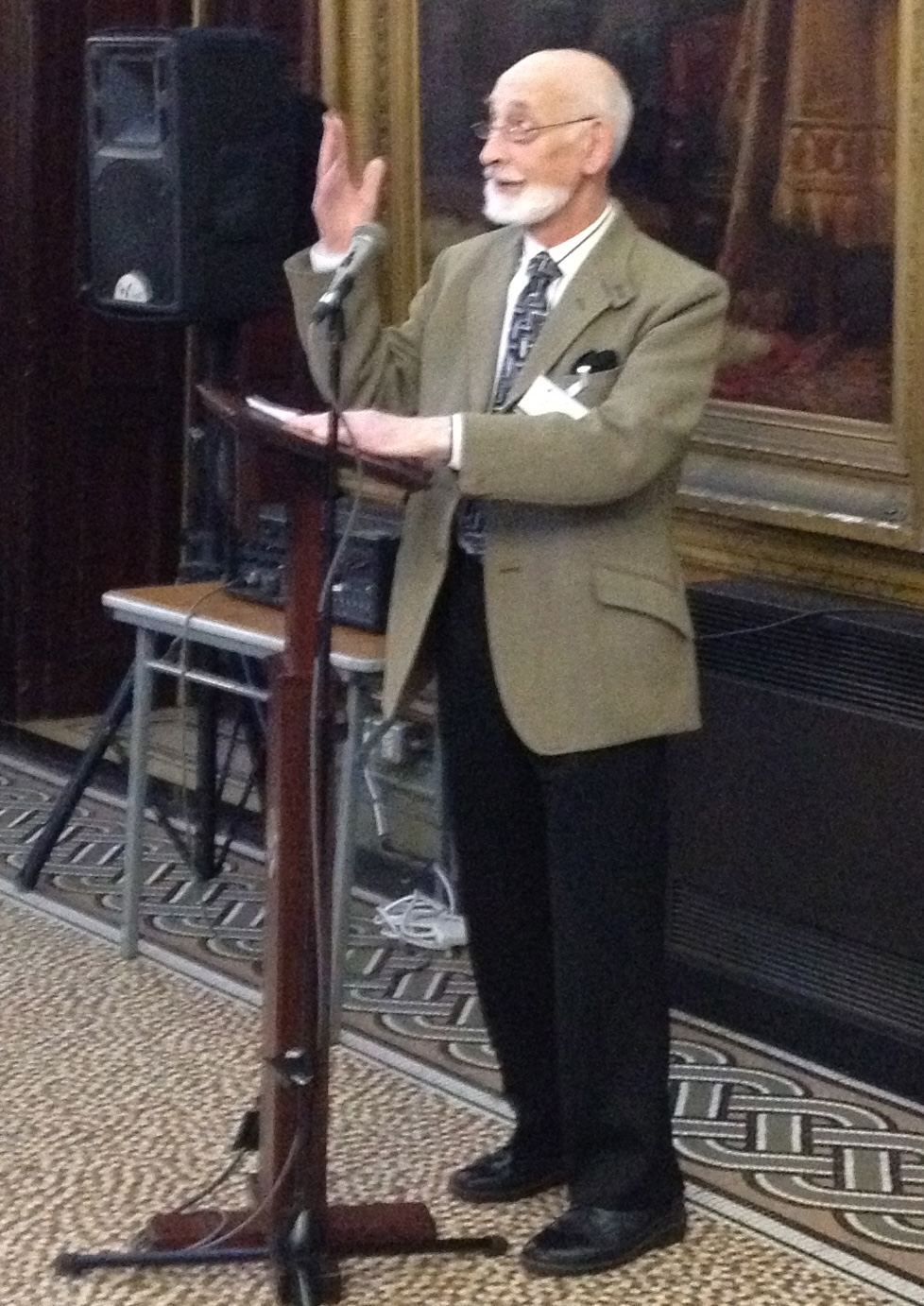

under-appreciated R.L. Scott collection, forever changed our craft. Although the field of “martial studies” is said to have been founded in the early 2000s, the case can be made that its godfather was undoubtedly Professor Sydney Anglo. Truly no single person can be credited with a greater impact on study of the fight books in the 21st century (certainly not those who merely passed along a handful of crude photocopies in the 1990s or dwelled on choreographed stunt-fights). Sydney grew up in Middlesex the youngest of six siblings from a half-Jewish family. He started his studies in 1954 at the prestigious Warburg Institute, one of the world’s leading centers for the study of art and culture. He then went on to a long teaching career at Swansea University in Wales and in 1957 married Margaret McGowan, who herself became a renowned scholar and historical author. Checking in on him every few months had become habit for me in the last few years, especially following the recent passing of his dear wife. I had last corresponded with him some weeks earlier where he had expressed that he felt he did not have much longer. But “Slasher Syd” as he so often signed off, retained his humor and acuity to the end. In the time before his passing, he had been slowly working towards completion of a book on pianists after the editing of his late wife's well-received recent work on Renaissance festivals —which itself contained a number of interesting observations regarding tournament displays and fight demonstrations. Sydney expressed that he found an immediate connection to the goals of the ARMA and our approach to studying the sources, complementing us on emphasizing prowess married with scholarship while deliberately avoiding the pitfalls of choreography, sport, and escapism. His influence behind the scenes was largely quiet and proceeded without interest in attribution or recognition —despite how often I would have proudly preferred to feature it (uncredited tips from him abound in many of my articles and editorials). It was a source of continual honor that he considered our efforts in the ARMA unique and praiseworthy. We even owe the very acronym we preferably use here for the craft —Marē— to the title of his pivotal book. Sydney’s writing was always engaging and never shied away either from ironic observation or understanding of brutality, even as he wrote in a style that demanded a thesaurus nearby. In fact, he complained at times about the plague of dull, lifeless, and all-but unreadable academic writing on martial history that even now plagues fight book scholarship —an observation we wholeheartedly shared. Yet, he also expressed personal pride in the wave of excellent new scholarship that has followed in his wake. He had expressed more than once some genuine surprise, and yet, a quiet satisfaction, at the significance his work on Renaissance martial arts has had worldwide, at first having only considered it an underrepresented area of historical study. As someone focused deeply on practical self-defence and the reality of fighting skills, what most fascinated me was his intuitive understanding of the underlying elements of personal violence that inescapably comprises Renaissance martial culture. He had none of the usual academic’s dry, detached, professorial disinterest in the bloody reality of close combat. Rather, he understood that was its very nature and key to approaching any study of the fight books. He only hinted that some of this came from personal experiences in his own youth. But even being the non-practitioner he was, I surprisingly found a kindred spirit in him and the respect and affection I felt only grew over the years. Sydney sponsored me in obtaining a coveted card to access the British National Library, where I was able to sit with the original of George Silver's Paradoxes among other works. And on one occasion I had the honor of enjoying cognac and cigars as a guest at his members-only London club for distinguished gentlemen. Being able to also include Sydney in the documentary film, Reclaiming the Blade, seemed to me absolutely essential.  Though

he had ended his research into Renaissance fighting disciplines shortly

after his book’s publication and in later years had stepped away from

the subject, he still retained a keen curiosity about it. He welcomed

the developments of which I would occasionally keep him informed through

correspondence and conversation. I last saw him in 2012 when we spent

time contemplating the influence of his writings and the direction our

subject had taken as a result. Yet, it was his sense of humor that I

found to be his most endearing quality (he had in fact done some comedy

radio shows in the 1950s, I recently learned). He never ceased to get a

chuckle from me one way or another, no matter the topic. His dual persona

of prim and proper British academic in public and casual jovial

antiquarian in private was endearing. I would sometimes jokingly refer

to him as the Gandalf of historical fencing studies, a title he

graciously dismissed. Though

he had ended his research into Renaissance fighting disciplines shortly

after his book’s publication and in later years had stepped away from

the subject, he still retained a keen curiosity about it. He welcomed

the developments of which I would occasionally keep him informed through

correspondence and conversation. I last saw him in 2012 when we spent

time contemplating the influence of his writings and the direction our

subject had taken as a result. Yet, it was his sense of humor that I

found to be his most endearing quality (he had in fact done some comedy

radio shows in the 1950s, I recently learned). He never ceased to get a

chuckle from me one way or another, no matter the topic. His dual persona

of prim and proper British academic in public and casual jovial

antiquarian in private was endearing. I would sometimes jokingly refer

to him as the Gandalf of historical fencing studies, a title he

graciously dismissed. On a personal note, I can say with honesty that the single greatest compliment I feel I have ever earned as a martial artist came not from a fellow fighter or one of my students, but from a professor of Renaissance studies. I had just completed at a museum conference a rather dynamic presentation on motus in fight book illustrations and combat artwork which concluded with a brief energetic demonstration of foot positions and stepping transitions. I retook my seat next to him and we awaited the next presenter. Sydney leaned over and whispered in my ear: “As splendid a display of sprezzatura as I think I have ever seen. Bravo.” I could not help but beam with pride —suspecting how less than a dozen attendees in the room likely even knew the significance of the term. I am proud to have known him and been enriched by his counsel over some 27 years of correspondence and conversation. His guidance was professionally and personally invaluable in my journey as a swordsman. His wisdom and counsel had a profound effect. He shall be missed, but his impact on all those he has educated and touched will not be forgotten. John Clements ARMA Director October 29, 2025 |