ARMA

Director John Clements answers Youth email on swords and swordsmanship:

Question: Why are there so many different kinds of sword, which one is better?

Question: Why are there so many different kinds of sword, which one is better?

To answer this question it must first be

understood that offense and defense are qualities that are in

competition in a sword. Historically speaking, a sword was a product of

the given technology and skill of the maker who created it. Some swords

might be stronger or sharper than others, and some better made than

others. Any design would be one that a fighting man needed to meet the

kind of challenges he expected to face in combat. These conditions

varied around the world at different times. This resulted in different

sword designs. But every type of sword was crafted as a solution to

similar problems of self-defense. Every sword had two essential

functions: to guard (or parry) and to strike (by cut, thrust, or both).

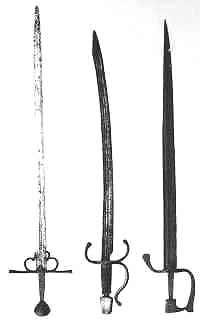

Since ancient times both cutting and thrusting

swords were known to be effective in single-combat as well as the

battlefield of war. Any sword would be expected to face other weapons

as well as armors. Armor could be of either hard or soft material, each

with differing degrees of resistance and maneuverability. All manner of

swords intended for cutting or for thrusting or for both were

constantly developed and tested to meet these challenges. Their blades

might be wide or narrow, thick or thin, straight or curved, single or

double-edged, tapered or un-tapered, sharply edged or not, and for one

or two hands.

But

any sword design is a compromise between certain contradictory traits:

a sword has to be hard to hold a sharp edge or sharp point but

resilient so as not to bend or break under stress. It must guard or

ward against other weapons as well as successfully damage targets

(armored or unarmored). No one sword achieves all the best effects of

every other kind. Some might be better used on foot than on horseback,

some better at fighting with a shield or second weapon, some better for

single combat or for the battlefield, and some superior at penetrating

soft armors or hard armor or even at fighting entirely unarmored.

That’s why in various cultures throughout history specialized varieties

of swords came to exist through generations of trial and error

experiment.

But

any sword design is a compromise between certain contradictory traits:

a sword has to be hard to hold a sharp edge or sharp point but

resilient so as not to bend or break under stress. It must guard or

ward against other weapons as well as successfully damage targets

(armored or unarmored). No one sword achieves all the best effects of

every other kind. Some might be better used on foot than on horseback,

some better at fighting with a shield or second weapon, some better for

single combat or for the battlefield, and some superior at penetrating

soft armors or hard armor or even at fighting entirely unarmored.

That’s why in various cultures throughout history specialized varieties

of swords came to exist through generations of trial and error

experiment.

Over time

different swordmakers experimenting and working in different places

came up with many different ways of making swords with assorted

characteristics that achieved the fighting needs of swordsmen in one

way or another. This is why sword blades will have different cross-sectional

shapes and edge-geometries that make them either stiffer or more

resilient and thus better at cutting or at thrusting.

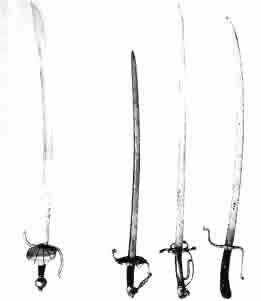

Not all sword types perform in the same manner. Sword designs

are actually specialized tools. Depending upon their cross-sectional

geometry, dimensions of length and width, and edge and point

configurations, some types will do one thing very well but not another.

The historical challenges of different battlefield and self-defense

needs resulted in a wide range of long bladed weapon designs (and

methods for effectively employing them). Some may have been intended

more for cutting or slashing at either hard or soft targets, thrusting

only at hard or soft targets, or a compromise somewhere in between. The

characteristic qualities that permit one action will hinder the other.

This gives different sword types different strengths and weaknesses

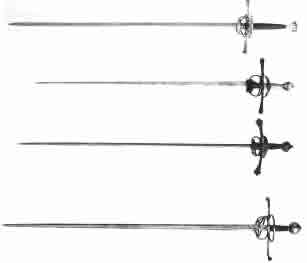

depending upon how and why they were expected to be used. What is important to understand is how with the eventual development

in Europe of slender single-handed thrusting swords, idea for unarmored civilian

dueling, is that they were not simply new “thinner” versions of earlier

wider swords suited to battlefield fighting. Rather, differences in blade geometry—in thickness as

well as width along its length—is an attribute of all types of sword.

This variation is precisely how various sword types are stiffer or more

resilient than another, may feel heavier or lighter in their hilt or

blade, and can be more adept at either thrusting or cutting at

different materials.

Each

sword design differs as to what it can do best within whatever kind of

fighting conditions it was created to perform under. Each has its

specialization, even if it is generalized.

The effectiveness of any sword strike depends on the kind of target

area hit in regard to the form or shape of the blade and severity of

the blow. Both cutting and thrusting techniques can each be more

effective or less effective depending upon the tactical context.

Writing on thrusting in his fighting treatise of the 1480s, the Italian

fencing master Filippo Vadi for example noted how, “Against one man the

thrust is good, but against many it does not work,” adding that both

books and actions confirmed this.

Each

sword design differs as to what it can do best within whatever kind of

fighting conditions it was created to perform under. Each has its

specialization, even if it is generalized.

The effectiveness of any sword strike depends on the kind of target

area hit in regard to the form or shape of the blade and severity of

the blow. Both cutting and thrusting techniques can each be more

effective or less effective depending upon the tactical context.

Writing on thrusting in his fighting treatise of the 1480s, the Italian

fencing master Filippo Vadi for example noted how, “Against one man the

thrust is good, but against many it does not work,” adding that both

books and actions confirmed this.

The variety of swords in history is immense. Different

sword types were rarely identified by their own distinct labels so

modern arms historians have classified or categorized them into

families of assorted kinds. Cutting and thrusting types could each be

decisive in sword combat but combined together they could be even more

so. Thus, the study of sword types and their characteristics, or spathology,

is an ongoing process that recognizes no one sword as absolutely

superior to any other. All of this is why there is no such thing as the

“perfect sword.”

Kids, Got Questions?

Send in your questions about swords or historical fencing to us.

We’ll do our best to answer any polite well-written question about Medieval and Renaissance close-combat

or provide you with references to learn more.