|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Anonymous late 16th Century German Fighting Guide - Codex Guelf 83. (c.1591) ARMA

Exclusive By Prof. Dr. B. Panconcelli-Calzia. Specialized German literature has some valuable manuscripts and books which provide an insight into the past of the German fencing arts since the 14th century. Recently, out of the vast amounts of text, a practical example came to me from the 16th century. It…shows beautiful hand-painted works and the great diversity of the subject. …I was able to wrest this gem from its sanctuary and release some of the enclosed paintings, resplendent in their original colors, for the first time. Let us…put ourselves on a 16th century fencing grounds. The manuscript will be our historical guide.

|

|

|

|

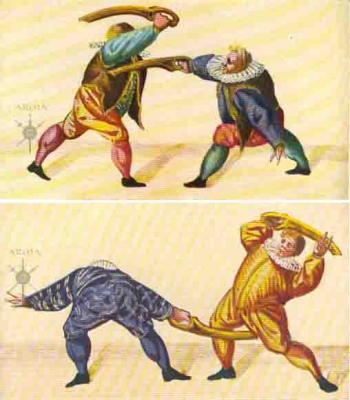

Let

us turn now to that part of the fencing-grounds where it is going notably

quiet and still. Aren't those boys each holding a dagger? Yes, and they

want to fence with them. There is no position taken, no greeting exchanged

- such formalities were completely unheard of until the middle of the

17th century - there are no overly lively or unnecessary movements made.

Each boy stalks and keenly observes his opponent every moment; it depends

on whether the man goes "high or low" at the other … "If

he goes high / you are allowed to get yourself nothing / and want the

parts / so you have in mind / freely take / But if he goes low / so have

yours in good wariness" ... says Master [Fabian von] Auerswald. A

movement from one of the fencers, to hit the opponent from above! Quickly,

he grabs the antagonist's right wrist, twists his arm around, so he loses

his senses, and stabs him in the thigh. Should the one fencer lose his

dagger or is surprised by an enemy while unarmed, he is then exclusively

dependent on the tricks of grappling. The second pair of dagger-fighters

have just shown a magnificent moment of this seemingly unfair fight; the

unarmed fighter grabbed the weapon-arm of his opponent with his right

hand, instantly bent it and through lifting his opponent's right leg to

the side, caused him to fall. Let

us turn now to that part of the fencing-grounds where it is going notably

quiet and still. Aren't those boys each holding a dagger? Yes, and they

want to fence with them. There is no position taken, no greeting exchanged

- such formalities were completely unheard of until the middle of the

17th century - there are no overly lively or unnecessary movements made.

Each boy stalks and keenly observes his opponent every moment; it depends

on whether the man goes "high or low" at the other … "If

he goes high / you are allowed to get yourself nothing / and want the

parts / so you have in mind / freely take / But if he goes low / so have

yours in good wariness" ... says Master [Fabian von] Auerswald. A

movement from one of the fencers, to hit the opponent from above! Quickly,

he grabs the antagonist's right wrist, twists his arm around, so he loses

his senses, and stabs him in the thigh. Should the one fencer lose his

dagger or is surprised by an enemy while unarmed, he is then exclusively

dependent on the tricks of grappling. The second pair of dagger-fighters

have just shown a magnificent moment of this seemingly unfair fight; the

unarmed fighter grabbed the weapon-arm of his opponent with his right

hand, instantly bent it and through lifting his opponent's right leg to

the side, caused him to fall. |

|

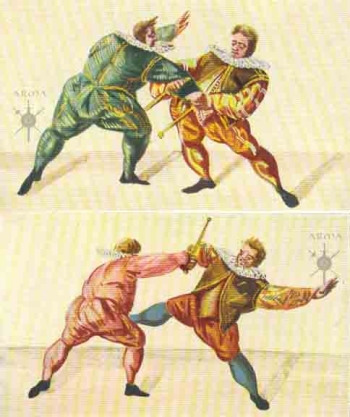

But

what kind of noisy activity is in the neighboring yard next to the fencing

grounds? There is also fencing going on here. These young men can only

practice outside, because their weapons are much too long. The long staves,

with which our lads in the yard fence, are the practice weapons for learning

the use of the long lance. In war, the men-at-arms also used shorter weapons

and they prepared themselves for these through the so-called half-staff.

Next to the boys with the half-staves stand others with halberds, which

because of their axe-blades - with which the enemy can be hooked - and

their points, were to be feared more in close-quarters combat than the

excessively long lance. But

what kind of noisy activity is in the neighboring yard next to the fencing

grounds? There is also fencing going on here. These young men can only

practice outside, because their weapons are much too long. The long staves,

with which our lads in the yard fence, are the practice weapons for learning

the use of the long lance. In war, the men-at-arms also used shorter weapons

and they prepared themselves for these through the so-called half-staff.

Next to the boys with the half-staves stand others with halberds, which

because of their axe-blades - with which the enemy can be hooked - and

their points, were to be feared more in close-quarters combat than the

excessively long lance.

It would be joyously welcomed, when next to the new [sport] weapons also the use of the old would be snatched from the past and again cultivated. Systematic attempts to revive the earlier German fencing arts were already started in 1924 by the author of these lines. The demonstrations, which always supplement the scientific lectures, were acclaimed by the audience, regardless if they were fencers or amateurs. If the fencing of the earlier Germans were to again gain respect and these fencing techniques properly cultivated, then could someone, for whom the modern sport-weapons show no promise, perhaps use two-handers, especially if he is stocky and strong, another, who is lighter and more agile, would probably decide on the dusack, etc. This should stay isolated not only for reasons relating to sports, but also for cultural history, for the cultivation and revival of old practices requires becoming acquainted with past cultural assets and so contributes to a deeper appreciation of the history of a people.

ARMA will feature more on this unique manuscript soon!

From Velhagen und Klasings Monatshefte, Jg. Berlin, 1926. Translation Copyrighted 2003 by Eli Combs. All righst reserved. |

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||