|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

By J. Clements |

|

|

I still freqeuntly

encounter practitioners who claim that in the historical source manuals

on longsword edges were used in parrying.

“Where are the flat parries described?”, they ask

(…the real question is, “Where are the edge parries

described?” But

we’ll come back to that). I now think there has been a tremendous misconception in asking about evidence for flat parries, and in wondering why they are seemingly not explained more carefully as blocking positions in the source manuals. I now believe people have more or less been looking for the equivalent of an 18th & 19th century conception of parries as used in sport saber fencing, which clearly aren’t there in the longsword material.

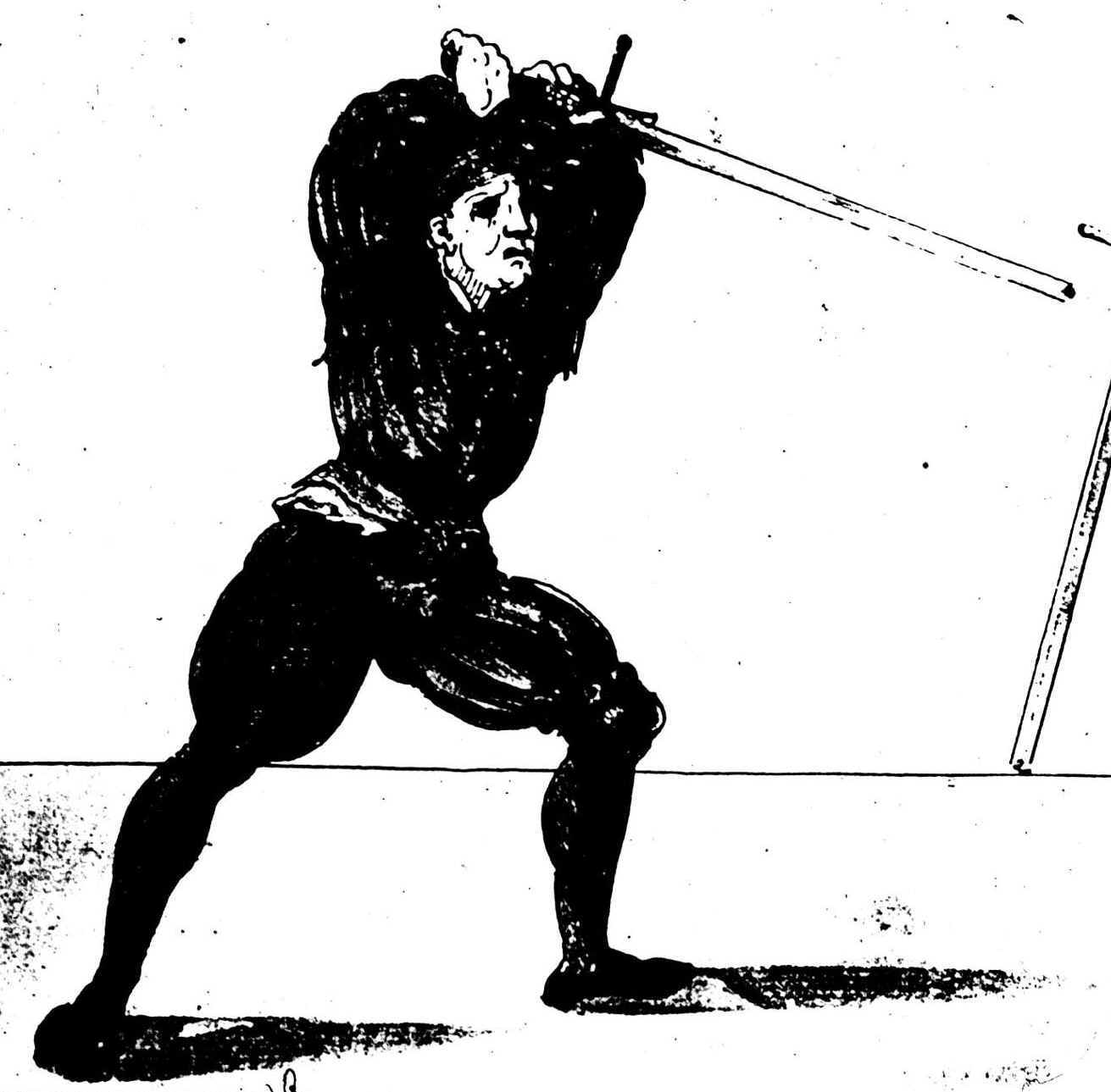

To explain, we must realize that source texts such as those by Mair and Meyer include two specific instructions for displacing “mit der flech” –with the flat. These are from the middle position of the plow and from the hanging technique (Pflug and Hangentorte). In both cases they say to receive the attacking blow on the flat so that it slips off or away. Doing each of these parries with the flat as instructed by the masters not only permits the flexible portion of the blade to take the impact, but keeps your edge aligned to make an immediate counter slice or cut. The Pflug and Hangentorte cover it all. They are the only two “direct parrying positions” really needed. The biomechanics of this are simplicity. Think about it: They protect from thigh to shoulder, and from head to elbow (lower attacks are defended by either slipping the leg away, striking the blow down, or even closing against it; plus both the high outside Ochs and the low Alber and Schrankhut positions can also be used as parries). Even the technique of the Schrankhut (the "crossed" or "barrier" ward), wherein leading with the left leg, the blade is held before the body on the right side, point down with the arms uncrossed, can itself be used to receive blows on the flat of the strong (as seen in Joerg Wilhalm's work of c.1523, for example). There's no need or value in doing it edge on. When performed correctly, this position, equivalent to a low Hengen, again leaves your edge poised to cut or to allow you to swiftly close in. Further, the four Hengen ("hangings") as first described by the master Liechtenauer, consisting of the Ochs and Pflug in Winden ("winding" on either side), can be interpreted as actually corresponding to all the possible positions achievable when engaging against the opponents blade while still maintaining your sword point aimed at them. Each position rises and lowers its hilt or point as necessary to maintain the contact, but still essentially holds an upper or lower Ochs or Pflug stance in guarding. This is one of the reasons why there is a close relationship between the Ochs position and the later Hangentorte ("hanging point") technique, as the upper Hengen are simply variations of Ochs performed in Winden. What is also interesting is that while simultaneously looking continually for openings, these positions also ward 360-degrees around the fighter, typically by keeping their flat oriented toward the opponent's blade. Thus, the reason there are not any other flat parries or numbered parrying positions described is because these two “passive” defenses can cover and protect against most any cut from any angle. This is not done statically as two separate actions of parry and riposte as in later saber fencing, but as one fluid motion of setting aside. Of this we are now fully convinced. As I’ve often advised, think about this well and give it a try for a lengthy time.

As to where instructions on edge parries are described in the Medieval and Renaissance manuals teaching on cutting swords…we are still waiting for evidence. We can’t find them anywhere –excepting when they say not to use them. |

|

|

|

| See Also: The Myth of Edge Parrying and Edges of Knowledge | |

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||