| Home | About ARMA | Where to Start | What's New | Forum | Spotlight | Articles & Essays | Research & Reading | RMA Web Documentary | Index |

|---|

|

|

|

ARMA

Director John Clements answers email on swords and swordsmanship:

|

|

|

|

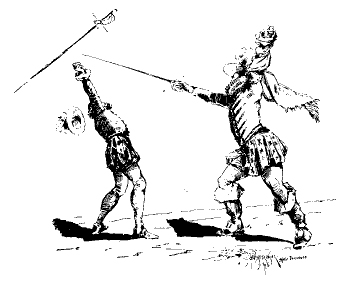

What would happen if you made cutting strikes with a rapier?

The

results of a rapier cut would be dependent upon many factors:

the mass and the edge configuration of the blade (a factor of

its cross-sectional shape and thickness), the angle of the cut,

the force behind the blow, the portion of the weapon that impacted

(closer to or farther from the point), and the location of the

strike on a person (against a softer or harder area). The Renaissance teachers

of the rapier frequently instructed to use cuts as secondary attacks

only when the adversary’s point was not directly threatening,

or they advised not to use them at all.

Given what has already been described above regarding the nature of rapier blades and their use in cutting, it can be surmised that the results of any cut might be that no harm would be done (because the edge turned and did not hit correctly, the blow was not hard enough, or the target area was too tough). Or the results might be a painful stinging injury to the face, arm, or leg, that causes a severe welt or a surface scratch and perhaps then annoys, infuriates, or intimidates the opponent. Or the results might be a lacerating wound to the musculature of the arm, leg, shoulder, or torso that inhibits to some degree the opponent’s freedom of action. It’s also conceivable (with a flatter, sharper edge) that the throat might even be slashed, the eyes blinded, and fingers or perhaps even a hand severed. From the historical accounts however, what we can believe the results surely would not be is immediate debilitation, incapacitation, or outright death.

From

my personal experience over the years using a wide variety of

sharp blades, including some antique rapiers, in test cutting

on numerous materials I have little doubt about how strikes with

the edge of rapiers would be employed. Depending upon the kind

of blade and portion of the arm used to strike with (shoulder,

elbow, wrist) our tests on fresh, raw meat produced nothing greater

than shallow surface cuts or tearing rips. Typically they made

little more than welts that did not even break tissue. If the

blade was flatter and wider, a hard blow with a quick, immediate

follow-on “drawing” pull caused a significant slicing wound. These

cutting results however were very poor compared to those possible

with wider kinds of heavier cutting blades, which can cleave and

shear to a considerable depth even through bone. Interestingly

though, slashes using the very tip of the rapier, even particularly

narrow ones, invariably would quite easily cause short ripping

tears in the meat. When we cut against soft cloth, the results

were even weaker. In all cases, the rapier cuts did not seem to

be sufficient to either disable the limbs of an aggressive man

or kill him on the spot.

From

my personal experience over the years using a wide variety of

sharp blades, including some antique rapiers, in test cutting

on numerous materials I have little doubt about how strikes with

the edge of rapiers would be employed. Depending upon the kind

of blade and portion of the arm used to strike with (shoulder,

elbow, wrist) our tests on fresh, raw meat produced nothing greater

than shallow surface cuts or tearing rips. Typically they made

little more than welts that did not even break tissue. If the

blade was flatter and wider, a hard blow with a quick, immediate

follow-on “drawing” pull caused a significant slicing wound. These

cutting results however were very poor compared to those possible

with wider kinds of heavier cutting blades, which can cleave and

shear to a considerable depth even through bone. Interestingly

though, slashes using the very tip of the rapier, even particularly

narrow ones, invariably would quite easily cause short ripping

tears in the meat. When we cut against soft cloth, the results

were even weaker. In all cases, the rapier cuts did not seem to

be sufficient to either disable the limbs of an aggressive man

or kill him on the spot.

Why is there controversy over cutting with a rapier?

A

“cut” is any blow with the edge of a sword, regardless of the

actual sharpness of such an edge or the capacity for that sword

to make an incise wound. So, just as a particularly curved sword

can still thrust, though not nearly as well as a straight one,

even a slender sword can “cut”, but not nearly as well as a wider

one. After all, even a car-antenna or a slender cane rod could

“cut” if you slashed someone with enough force and hit them on

the right spot.

A

“cut” is any blow with the edge of a sword, regardless of the

actual sharpness of such an edge or the capacity for that sword

to make an incise wound. So, just as a particularly curved sword

can still thrust, though not nearly as well as a straight one,

even a slender sword can “cut”, but not nearly as well as a wider

one. After all, even a car-antenna or a slender cane rod could

“cut” if you slashed someone with enough force and hit them on

the right spot.

If we think of edge blows with a light, slender, rigid blade not in terms of being shearing blows intended to incapacitate, but rather as distracting and harassing actions designed to open the opponent up to a more lethal thrust, then “cutting” with a rapier can make sense. These cuts will hurt, they can bruise, they will likely break skin and more, but they won’t stop an attacking man intent on killing.

Misunderstanding over cutting with a rapier frequently comes about when people with rapiers try the things they see in movies and TV shows (cutting through ropes and belts and clothing, etc.). Or else they rapier fence with super light and thin sport epees or foils and try to chop and hack like they are using a wider arming sword. Or worse, they fence very sloppy with flexible practice rapiers and when recovering back from missing a thrust, in the process brush the blade against their opponent and then yell, "I cut you! You're disabled!" To justify all this they quote and misquote the source texts, ignore historical and physical evidence, and misrepresent the actual handling and performance characteristics of the real weapons. The solution, as we see it, is educating enthusiasts as to the actual effects of applying the actual techniques using real weapons. It’s a process that will take time, since we are all still exploring.

Noticeably, today’s’ enthusiasts of the “rapiers cut everything” view consistently misrepresent the teachings of historical rapier masters so that they utterly fail to distinguish the substantial differences between edge blows by wider cleaving and shearing blades that kill and disable, and those by lighter, narrower, thrusting blades that simple harass, distract, provoke, and injure. They completely ignore the criticism of the rapier’s lack of significant cutting capacity as stated by historical writers such as Silver and Smythe. They provide no examples of historical combats in which rapier cuts alone actually kill anyone and they ignore modern experiments that objectively demonstrate the poor cutting ability of slender rapier blades. They instead try to purposely obscure the differences between military cut-and-thrust swords (or “early” rapiers) from later civilian duelling weapons (or “true” rapiers). The apparent motive for this is a personal need to maintain a pre-conceived conception of sword combat for “play” within their own pretetious make believe duelling games.

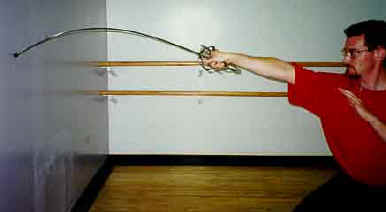

Could bare hands be used to grab or parry a rapier blade?

Rapiers

were quick and agile, but they could still be quickly seized and

held tightly by even a bare hand. There would be little chance

of the hand being injured in doing this. Indeed, as the historical

texts instruct, even wider cutting swords can be held by the blade

or grabbed safely if done correctly. Several rapier treatises

depict the empty hand being used to slap away or deflect rapier

thrusts. This was a common technique and because a man might

easily close to grapple in this way, it was another reason to

employ a dagger or other weapon in the second hand. If a special

grasping glove covered in maile or heavy leather was worn then

grabbing or swatting away a sword was even safer.

Rapiers

were quick and agile, but they could still be quickly seized and

held tightly by even a bare hand. There would be little chance

of the hand being injured in doing this. Indeed, as the historical

texts instruct, even wider cutting swords can be held by the blade

or grabbed safely if done correctly. Several rapier treatises

depict the empty hand being used to slap away or deflect rapier

thrusts. This was a common technique and because a man might

easily close to grapple in this way, it was another reason to

employ a dagger or other weapon in the second hand. If a special

grasping glove covered in maile or heavy leather was worn then

grabbing or swatting away a sword was even safer.

How were rapiers gripped or held?

Rapiers

were both balanced and gripped in a manner that facilitated point

control for accurate thrusting rather than edge control for strong

cutting. Their handle shapes were devised with this in mind and

permitted them to more effectively jab by extending the arm. The

primary grip was actually one which permitted them to be easily

drawn from the thigh by pulling the arm straight up above the

head. This typically involved the thumb being placed on the flat

of the guard at the core or écusson. Other grips consisted

of “fingering” or wrapping the index finger around the cross and

ricasso. Two fingers might also be used like this with the thumb

put on the edge of the ricasso. A strong hand might even grip

the weapon only by the pommel in order to gain extra reach. The

grip used was whichever suited the technique or the swordsman.

Why is there controversy over how the rapier was used?

The

Renaissance fighting styles changed so much over time that they

died out and now no one alive knows for sure how it was done back

then. Different swords often require different methods of using

them and this leads to different styles of fighting. These change

over time and there is no one alive today who really knows the

forgotten styles. The old teachings have been lost from disuse

and the old styles went extinct due to their obsolescence. Any

modern enthusiast or student of swords must therefore interpret

the old texts and rediscover how to handle the old weapons. Yet

few individuals now possess the knowledge or experience with real

weapons and genuine Renaissance fighting techniques to demonstrate

them correctly. There is also a lot of misinformation on the

Internet from those who base their understanding of the rapier

more upon modern sport fencing rather than the actual weapons

and historical source works. So, in the process, misconceptions

develop from assumptions that are made and from the misrepresentations

that exist in the pretend sword fighting of games and entertainment.

The examples of swordplay we see today portrayed in movies, TV,

sport fencing, as well as many Renaissance fairs and reenactment

societies, do not offer the most accurate picture.

The

Renaissance fighting styles changed so much over time that they

died out and now no one alive knows for sure how it was done back

then. Different swords often require different methods of using

them and this leads to different styles of fighting. These change

over time and there is no one alive today who really knows the

forgotten styles. The old teachings have been lost from disuse

and the old styles went extinct due to their obsolescence. Any

modern enthusiast or student of swords must therefore interpret

the old texts and rediscover how to handle the old weapons. Yet

few individuals now possess the knowledge or experience with real

weapons and genuine Renaissance fighting techniques to demonstrate

them correctly. There is also a lot of misinformation on the

Internet from those who base their understanding of the rapier

more upon modern sport fencing rather than the actual weapons

and historical source works. So, in the process, misconceptions

develop from assumptions that are made and from the misrepresentations

that exist in the pretend sword fighting of games and entertainment.

The examples of swordplay we see today portrayed in movies, TV,

sport fencing, as well as many Renaissance fairs and reenactment

societies, do not offer the most accurate picture.

Did rapiers ever face broader or heavier style Medieval swords?

By

time the rapier came about, older styles of traditional military

swords and Medieval weapons (used primarily for facing armors)

were generally obsolete on the battlefield and were no longer

carried for general self-defense on the street either. While they

still had application and were studied to a degree in traditional

schools of fencing during the 1500s, the new rapier was not designed

or intended to defeat them. From time to time it was possible

to still encounter the older weapons in single combat and there

is evidence the rapier then proved a difficult challenge. But

it must be considered that unlike the new civilian rapier, due

to changing military conditions, these broader and heavier weapons

were largely past their prime and thus were not being practiced

as intently as they once had been. So, as a weapon of street-fighting

and single-combat duelling, it is not a matter of the rapier having

somehow "defeated" or "overcome" Medieval

swords.

By

time the rapier came about, older styles of traditional military

swords and Medieval weapons (used primarily for facing armors)

were generally obsolete on the battlefield and were no longer

carried for general self-defense on the street either. While they

still had application and were studied to a degree in traditional

schools of fencing during the 1500s, the new rapier was not designed

or intended to defeat them. From time to time it was possible

to still encounter the older weapons in single combat and there

is evidence the rapier then proved a difficult challenge. But

it must be considered that unlike the new civilian rapier, due

to changing military conditions, these broader and heavier weapons

were largely past their prime and thus were not being practiced

as intently as they once had been. So, as a weapon of street-fighting

and single-combat duelling, it is not a matter of the rapier having

somehow "defeated" or "overcome" Medieval

swords.

Were rapiers ever taken into battle during wars?

There are some accounts of rapiers being carried into battle, particularly by mounted officers (the least likely to engage in close combat), but not of any rapier being effectively used in actual fighting. Many military writers during the rapier age advocated the use of tucks (short stiff thrusting swords) and later authors sometimes mistook these swords as being “rapiers.” Several authors of the time complained specifically of the rapier not being suited to the battlefield while others said it was fine.

Were rapiers ever used against armor?

Rapiers

were not designed nor intended to be employed against armored

opponents. Yet, encountering armor was a common occurrence for

any fighting man of the time. Rapiers were capable of piercing

soft armors but historical evidence shows that fine maile (chain-link

armor) was a sufficient defense and was often worn under clothing

for this very reason. If an opponent were wearing any portion

of plate armor, which was still possible on the battlefields and

within urban militias of the 1500s and 1600s, attacks would naturally

be directed to other more vulnerable areas. At times, for

aesthetic reasons today museums will often display suits of 16th

century plate armor holding or wearing rapiers, even though these

were not used together in war, tournaments, or private self defense.

Who carried or wore the rapier?

Though

associated with late Renaissance gentlemen, the rapier at various

times was carried and used by all classes and the earliest references

to the weapon’s use from the 1540s to 1560s, in fact, concern

common urban self-defense, not aristocratic private duels. While

the rapier is often associated with cavaliers and courtiers of

the aristocracy, it in fact originated as a weapon of street fighting

among commoners, merchants, and shopkeepers. Though swords worn

with civilian dress (as opposed to battle dress) may have begun

with the nobility at court, the need for a self-defense weapon

was also felt by ordinary citizens. As the foyning method developed,

however, it came to be employed more and more by that class which

most engaged in private duels of honor, the nobility. Within a

generation it became a popular martial skill to study for most

sophisticated Renaissance gentlemen. In some places it was

a fad to study in private the “secrets” of an exotic style under

a foreign master. As with later smallswords (the duelling blade

of 18th century gentlemen) some rapiers were also carried

by unskilled men simply as symbols of rank and authority.

Did the rapier require special training to learn?

Every

sword requires specialized training in order to use it to its

fullest capacity and the rapier was no different. However, it

has been said that slashing or chopping with a cutting blow is

much more instinctive than delivering a straight thrust. Unlike

earlier traditions of martial arts in Renaissance Europe which

focused on battlefield use and general self-defense skills, the

thin and light rapier required a change in the stance as well

as the footwork in order to gain maximum reach while avoiding

being stabbed or cut in return. So, over a generation or two a

new method of training was specifically developed as preparation

for the unique nature of fighting a duel with a rapier against

another rapier.

Every

sword requires specialized training in order to use it to its

fullest capacity and the rapier was no different. However, it

has been said that slashing or chopping with a cutting blow is

much more instinctive than delivering a straight thrust. Unlike

earlier traditions of martial arts in Renaissance Europe which

focused on battlefield use and general self-defense skills, the

thin and light rapier required a change in the stance as well

as the footwork in order to gain maximum reach while avoiding

being stabbed or cut in return. So, over a generation or two a

new method of training was specifically developed as preparation

for the unique nature of fighting a duel with a rapier against

another rapier.

Rapiers could in their time reasonably expect to face a range of cutlasses, sabres, broadswords, two-hand swords, and daggers, as well as bucklers and pole-weapons while still encountering buff coats, chest plates, and maile armor (sometimes worn under clothing). So a man would need to learn in general how to “fight”, not simply “fence” with rapier against rapier.

Rapier fencing was taught by gentlemen and nobles, true, but this had always been the case with virtually all earlier forms of swords and weapons. Most every form of fighting was practiced by the aristocracy in Western Europe during the Middle Ages and Renaissance and taught in private or at court. The rapier was no exception to this. Yet, as with earlier weapons, it was also taught by professional instructors who were common tradesmen and soldiers.

Did fighting with the rapier involve any grappling or wrestling?

With

few exceptions, until sometime in the 1700s all sword combat invariably

involved grappling and wrestling as an important component. A

skilled fighter could always close in with his opponent to disarm

or throw him or otherwise trap him in some way. He also had to

be able to defend against his opponent doing the same. A weapon

certainly helps you to fight, to protect yourself from blows,

and to deliver lethal ones of your own. But it does not entirely

eliminate the possibility of an enemy getting at you and grabbing

hold.

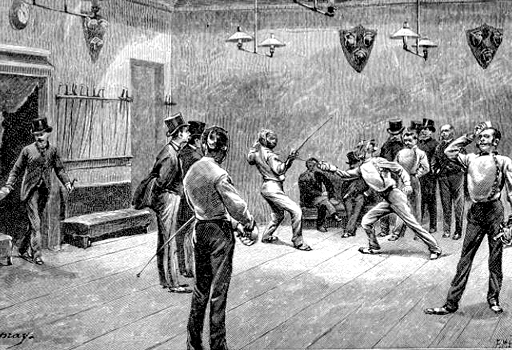

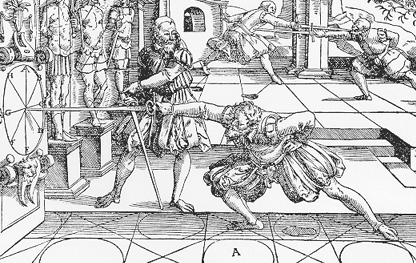

How did a swordsman learn and practice rapier fencing?

In the age of the rapier men had to train carefully even though they were learning how to fight for real. If a man were injured by a practice partner he might easily be blinded or maimed for life and thus, be unable to work or earn a living. He might also seek revenge for the accident by assassination or murder.

To

learn effectively how to fence together men therefore had to be

cautious but trusting. Blunted and unpointed weapons, originally

called “foyled” blades, were typically used that would not hurt

if they hit too hard. Additionally, agreements to abide by certain

safety rules for practicing were made, such as not aiming blows

at the face. Men would exchange as drills certain pre-arranged

attack and defence actions and, eventually, conduct open bouts

of mock combat. But even then, they were careful not to thrust

too high or too hard. Without the fencing masks developed in the

1700s, they simply had to be wary and alert. Yet this approach

evidently proved effective enough and surely must have developed

alert and precise fighters.

The physics of thrusting swordplay, unlike the dynamic clashing of broader blades, can be worked out and learned slowly, provided care is taken. Though developing the quick vigorous skills for actual combat still required considerable exercise. As with any method of fighting, rapiers were taught through a series of drills and exercises that conveyed the weapon’s techniques along with core principles of fighting (that is, timing, distance, technique, etc.). However, just what the lessons were and how they were passed along is something we no longer have any record of and can only speculate on in our reconstructions. The key or foundational elements of the weapon are clear enough from the surviving historical study guides. Still more has been learned from literature of the period and modern experiments. But just how rapier fencers actually practiced their craft is something still being explored at the present.

Men

learning to fight with a rapier would have been taught fundamental

warding postures or fighting stances, basic attacks, how to step

and move, and how to deal with attacks by putting them aside,

evading them, or closing in against them. They would have been

taught awareness of the different divisions of the blade, where

it was stronger or weaker when pressed or pressing. They would

have been instructed in using their free hand or dagger to parry,

trap, or strike and they would have learned when to hit with their

hilt and when to grapple and wrestle as needed.

Men

learning to fight with a rapier would have been taught fundamental

warding postures or fighting stances, basic attacks, how to step

and move, and how to deal with attacks by putting them aside,

evading them, or closing in against them. They would have been

taught awareness of the different divisions of the blade, where

it was stronger or weaker when pressed or pressing. They would

have been instructed in using their free hand or dagger to parry,

trap, or strike and they would have learned when to hit with their

hilt and when to grapple and wrestle as needed.

There were schools and masters of Renaissance martial arts all over Europe teaching swordplay in the 1500s and 1600s. According to some teachers of the age the rapier’s manner of fight was actually very easy to acquire. It was still highly methodical, often presented with a wrapping of geometry and involved jargon, and frequently viewed as more refined and scientific than the traditional “military” fencing that it largely replaced off the battlefield. One master in 1617 even claimed a boy of fifteen could learn to defend himself against any man in very few lessons. Other teachers wrote the rapier’s basis could even be learned without a teacher.

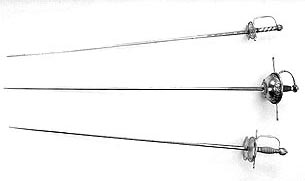

How were rapiers made?

Because

they did not require especially hard edges, nor great flexibility,

a rapier was actually not that difficult to produce. As with any

sword it had to be both strong and resilient. It had to be able

to withstand blows without breaking but it also had to be able

to hold an edge or point without staying bent or dulling instantly

after an impact. As swordsmiths now will point out, there is an

almost infinite variety of ways to produce such a slender sword

with one geometric shape or another that adds rigidity and lightness.

(Despite the many different rapier blade shapes I have not seen

a modern replica yet today that unfortunately doesn't rely on

the same simple flat-diamond shape, even though this represents

only one small form of earlier rapier blade styles).

There

are several modern myths about how swords are made. Select iron

ore had to be first processed by heating and working it into steel

before it could be shaped. Swords were never made by pouring

molten metal into molds (this would only produce a brittle and

weak cast-iron shape). Swords were also not created by pounding

red hot metal into shape on an anvil. Rather, after heating, the

material had the consistency of soft clay and needed to be carefully

and gradually hand-shaped by a skilled craftsman slowly and softly

working it. Blades were also not made by merely quenching (dunking)

them into water or some other liquid while red hot. This merely

was a finishing step in hardening the outside after a final careful

reheating. Before this a complex process of slow tempering (heat-treating)

was conducted to ensure the blade had the right stiffness and

resilience. This part was a major aspect of a swordsmith’s art.

Most

every kind of sword blade involves combining a softer inner core

of iron with a harder outer surrounding of steel. Getting this

“sandwich” combination right for the kind of job a particular

blade was being called upon to perform was not easy. Most blades

were produced by a folding process (something not exclusive to

Japanese swords) which mixed the required attributes of hard and

soft metal. Finally, their end shape would be produced by hand

grinding and polishing. To test rapiers, they would be thrust

and flexed against a resistant target. This was not to make sure

they could repeatedly flex, for that was not what they were intended

for, but rather to test whether they were well tempered and durable.

If made too stiff they would snap, if too soft they would not

recover from the bend. They might also be thrust against a softer

material to see how easily they pierced it.

While the basic geometry of a rapier blade was probably produced in the forging process, the final shape and the beveled facets of the edge would likely have been created by grinding (perhaps even after the blade had been heat treated). Compared to those on a broad cutting sword, the tapers and cross-sectional changes on a narrow stabbing blade would also be minimal. Additionally, a thin blade would be less likely to distort or warp during the hardening by heat (tempering) process.

Are

practice rapiers and modern replicas different than the real ones?

Real rapiers were quite stiff. They needed to be very rigid in order to easily thrust into human bodies when trying to harm an enemy. If not, they would be unable to successfully puncture through material such as cloth, leather, flesh, and even bone. They also had to be able to deliver techniques as well as deflect and beat other blades without wobbling or whipping. To ensure this, rapiers were made with cross-sections that added rigidity and strength without being too thick or heavy. They were also tempered in such a way to give them additional stiffness while retaining the necessary resilience. Today, instead of being properly rigid most all reproduction rapiers are made much too flexible and sometimes even wobbly.

This

is perhaps due to the desire by many rapier fencing aficionados

to have a safe practice weapon while sparring that will easily

bend to a considerable degree without breaking or accidentally

penetrating. But this degree of flexibility, appropriate for sport

weapons, affects the way such blades perform and distorts the

true techniques of real rapier fencing. There is also so far no

actual evidence of any flexible practice rapiers having ever been

used in the Renaissance. Bendable practice weapons for foyning

fence do not seem to appear prior to the use of the smallsword

in the late 1600s. Surviving specimens of “practice” rapiers from

the Renaissance are themselves quite stiff and not overly flexible.

However, there are many examples in both artwork and literature

from the age of practice rapiers with large ball tips for safe

training. These were used from at least the 1560s.

This

is perhaps due to the desire by many rapier fencing aficionados

to have a safe practice weapon while sparring that will easily

bend to a considerable degree without breaking or accidentally

penetrating. But this degree of flexibility, appropriate for sport

weapons, affects the way such blades perform and distorts the

true techniques of real rapier fencing. There is also so far no

actual evidence of any flexible practice rapiers having ever been

used in the Renaissance. Bendable practice weapons for foyning

fence do not seem to appear prior to the use of the smallsword

in the late 1600s. Surviving specimens of “practice” rapiers from

the Renaissance are themselves quite stiff and not overly flexible.

However, there are many examples in both artwork and literature

from the age of practice rapiers with large ball tips for safe

training. These were used from at least the 1560s.

|

By the mid-1600s, as fashion, firearms, and necessity altered the need for personal self-defense weapons, the long bladed, large-hilted rapier fell out of general use. Much lighter, shorter versions developed which in time came to be known as smallswords (sometimes also called court-swords, town-swords, or walking swords). The distinction between the conditions under which civilian rapiers and gentlemanly smallswords were each used greatly influenced their development and design. The lighter, shorter, quicker smallsword was not an inherent innovation over the earlier rapier and did not “outfight” it. Rather than the smallsword design being in itself any great virtue over the longer rapier, it was instead developed for more specific and narrow circumstances. The smallsword was a more poised, somewhat formalized, dueling weapon whose teachings involved as much deportment and composure as it did technique. In contrast to the longer rapier, the smallsword fencing style, using a much shorter and lighter blade, made a separate parry and riposte (counter-attack) as two distinct movements. |

|

|

The

smallsword’s method of both parrying and counter-attacking as

two separate actions (in “double time”) was not an intrinsic “improvement”

over earlier methods of fighting—which employed simultaneous actions

of offense and defense by counter-blow—but an adaptation. When

an exceptionally light thrusting sword came about, purposely developed

for civilian duelling with another similar weapon, it naturally

could affect two separate motions out of the action of parrying

a thrust and returning another. This was no great advancement

in fencing theory as much as common sense fighting by using a

weapon’s intrinsic speed to its logical technical advantage.

The

smallsword’s method of both parrying and counter-attacking as

two separate actions (in “double time”) was not an intrinsic “improvement”

over earlier methods of fighting—which employed simultaneous actions

of offense and defense by counter-blow—but an adaptation. When

an exceptionally light thrusting sword came about, purposely developed

for civilian duelling with another similar weapon, it naturally

could affect two separate motions out of the action of parrying

a thrust and returning another. This was no great advancement

in fencing theory as much as common sense fighting by using a

weapon’s intrinsic speed to its logical technical advantage.

Many elements native to the rapier were naturally carried over with the fighting style of the smallsword. But with each generation of fencers, as instances for self-defence with a sword became less and less frequent while duelling became more and more ritualized and sporting play increasingly replaced earnest fighting, fewer aspects of the older rapier were maintained. In time, it took on a character all its own-one which owed far more to baroque sensibilities of deportment than practical Renaissance street-combat.

How does rapier fencing of the Renaissance compare to modern fencing styles?

Modern s

sport fencing developed in the late 1800s from styles of fencing

created in the 1700s at a time when fewer kinds of swords were

being used by fewer men under less varied conditions. It is the

smallsword, and not the earlier rapier, from which modern sport

fencing styles are directly derived. It has far more in common

with this humble weapon than it does with rapiers or any earlier

Renaissance swords. Modern fencing’s “weapons” were in fact

never real swords. They were designed specifically for simulation

in a safe duelling game. They are much lighter, softer, and faster

than their historical counter-parts. Their specialized rules of

play observe artificial constraints that have very little to do

with any elements of Renaissance swordsmanship. Despite what

many people commonly try, real rapiers, being heavier, stiffer,

sturdier, and with larger hilts than today’s relatively flimsy

sporting weapons, cannot be used in the same flippy manner as

modern fencing does (and vice versa).

Modern s

sport fencing developed in the late 1800s from styles of fencing

created in the 1700s at a time when fewer kinds of swords were

being used by fewer men under less varied conditions. It is the

smallsword, and not the earlier rapier, from which modern sport

fencing styles are directly derived. It has far more in common

with this humble weapon than it does with rapiers or any earlier

Renaissance swords. Modern fencing’s “weapons” were in fact

never real swords. They were designed specifically for simulation

in a safe duelling game. They are much lighter, softer, and faster

than their historical counter-parts. Their specialized rules of

play observe artificial constraints that have very little to do

with any elements of Renaissance swordsmanship. Despite what

many people commonly try, real rapiers, being heavier, stiffer,

sturdier, and with larger hilts than today’s relatively flimsy

sporting weapons, cannot be used in the same flippy manner as

modern fencing does (and vice versa).

By the mid-19th century it was already being recognized that fencing was changing further. Things that could be safely done in the fencing classroom with blunt flexible weapons and protective masks would never be attempted in real fights with sharp blades. This process of transition from martial art to martial sport accelerated with each decade. Techniques possible with feather weight tools designed for a game of scoring points would be suicidal in a real duel. But increasingly these actions alone were the only ones permitted in friendly competitive bouting, and thus, were the only ones being taught any longer.

Though

rapiers and later smallswords, foils, and epees all utilize similar

core movements (since they are all forms of foyning fence) on

the whole there are considerable differences between them. Many

elements of rapier fighting described in accounts of combats and

duels or taught within texts from the period are simply illegal

in the modern sport. There is no use of either secondary weapons

or the free hand, for example, and combatants are not permitted

to use too much force against their adversary’s blade. This alone

in itself alters the nature of the fight and the techniques used

significantly. There is no blade grabbing or manual disarms allowed,

nor can the fighter grab his own blade with both hands in any

manner. There are also no cutting strikes at all used with later

foyning weapons, even if just to aggravate and harass the opponent

and sometimes no blows are delivered below the waist. There is

no body contact permitted at all in modern fencing, and certainly

no grappling allowed to hold or trip or throw the opponent. This

alone fundamentally changes the approach and attitude brought

to such a fight.

Though

rapiers and later smallswords, foils, and epees all utilize similar

core movements (since they are all forms of foyning fence) on

the whole there are considerable differences between them. Many

elements of rapier fighting described in accounts of combats and

duels or taught within texts from the period are simply illegal

in the modern sport. There is no use of either secondary weapons

or the free hand, for example, and combatants are not permitted

to use too much force against their adversary’s blade. This alone

in itself alters the nature of the fight and the techniques used

significantly. There is no blade grabbing or manual disarms allowed,

nor can the fighter grab his own blade with both hands in any

manner. There are also no cutting strikes at all used with later

foyning weapons, even if just to aggravate and harass the opponent

and sometimes no blows are delivered below the waist. There is

no body contact permitted at all in modern fencing, and certainly

no grappling allowed to hold or trip or throw the opponent. This

alone fundamentally changes the approach and attitude brought

to such a fight.

Why

did rapiers fade away?

Why

did rapiers fade away?

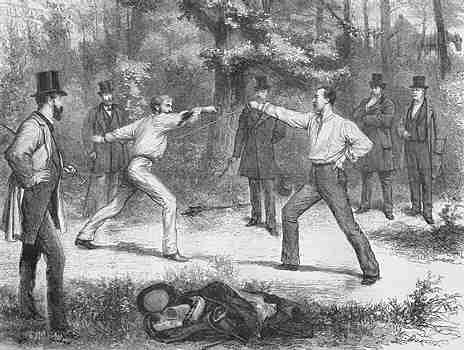

The rapier era was active for some 150 years, just long enough for several varieties of the weapon and several fighting theories for using them to have evolved before firearms made them truly obsolete for personal self-defense. The rapier stayed in wide use as the premier personal weapon for urban self-defence and duel of honor in Western Europe until the mid-to-late 1600s, but was largely outmoded by the early 1700s. Their long blades and elaborate hilts were largely impractical in the changing social environment, where they were an encumbrance while walking through crowds, dancing at balls, sitting in formal rooms, getting in and out of carriages, etc. As the daily wearing of swords about town and at court declined there was no longer the opportunity for sudden challenges and assaults as there once was. Similarly, there was no longer the same urgent necessity to employ a dagger or suddenly parry a thrust with the bare hand. Thus, rapiers fell out of use. It took time however before the tens of thousands of excellent rapiers then in existence were slowly modified or abandoned by men seeking more fashionable, shorter swords.

What makes the rapier special?

As

a personal weapon of urban self-defense, the vicious and elegant

rapier became the dueling tool par excellence. In

my opinion (speaking also as avid admirer of both longswords and

sword & buckler fencing), for single unarmored duels with

a sword, in skilled hands the slender rapier is a vicious and

formidable weapon for single combat not to be underestimated (especially

by those unfamiliar with its unique style of fight). Its method

is quick, deceptive, subtle, and represents one of the most innovative

and original aspects of our Western martial heritage.

As

a personal weapon of urban self-defense, the vicious and elegant

rapier became the dueling tool par excellence. In

my opinion (speaking also as avid admirer of both longswords and

sword & buckler fencing), for single unarmored duels with

a sword, in skilled hands the slender rapier is a vicious and

formidable weapon for single combat not to be underestimated (especially

by those unfamiliar with its unique style of fight). Its method

is quick, deceptive, subtle, and represents one of the most innovative

and original aspects of our Western martial heritage.

The rapier was distinct in Western European sword history in that it represented a specialization of design—that is, a weapon optimized for unarmored single-combat rather than fighting most anywhere, anytime, or under any conditions. It was strictly a personal weapon, never used or intended for war or battlefield. However, what a rapier arguably did best was fight another rapier. As a slender, civilian thrusting sword the rapier was a sophisticated and highly effective form of personal combat, vicious and elegant in its lethality.

How come so many different looking sword blades seem to have been called “rapier” over such a short span of time?

This is not a hard concept to grasp. Regardless of the names continually evolving for different types of swords in the period, there were tapered single-hand swords and then there were rapiers (hence, the new methods of civilian fencing that developed in the 16th century). The weapons are not identical and do not perform or handle identically. This is self-evident in handling original specimens and in test-cutting with modern reproductions of each type. Military and civilian blades of radically different cross-sectional profiles are simply not synonymous. They cannot all be employed as some foil/saber hybrid. Arguing that they do is an astounding display of idiocy and ignorance. The whole idea is simply that there was a new slenderer, tapered, single-hand sword blade becoming popular that was not intended or suited for military use and which emphasized thrusts. These weapons eventually grew so slender that they lost all cutting capacity as they developed a particular method of counter-thrusting use. Oddly, despite the sometimes view that all slender Renaissance swords and rapiers are essentially the same, it is not generally claimed that rapiers and later smallswords are identical even though many smallswords were merely rapier blades shortened and given different hilts. It makes even less sense then to argue that blades of radically different cross-sectional profiles are somehow synonymous.

How can someone start studying the rapier now?

If

you want to begin exploring the rapier without spending hundreds

of dollars on equipment, you can purchase an inexpensive wooden

rapier waster, try working with some of the material in my ’97

Renaissance Swordsmanship book as a basis for study (in

which many of the elements raised here are addressed), and read

through the many rapier articles and manuals online here at the

ARMA website. Practice thrusting against a target, moving by

stepping quickly forward and back and diagonally while thrusting,

and practice lunging and thrusting while using the left hand to

parry and trap. It’s really not a difficult weapon to practice

(as one master even said) once you have grasped the simple foundation

of its method. It just takes time and sufficient effort. The

seemingly complicated exchanges of rapid thrust and counter thrust

of foyning fence can appear highly technical and indecipherable

to the uninitiated beginner, but there really are only a few movements

at work.

If

you want to begin exploring the rapier without spending hundreds

of dollars on equipment, you can purchase an inexpensive wooden

rapier waster, try working with some of the material in my ’97

Renaissance Swordsmanship book as a basis for study (in

which many of the elements raised here are addressed), and read

through the many rapier articles and manuals online here at the

ARMA website. Practice thrusting against a target, moving by

stepping quickly forward and back and diagonally while thrusting,

and practice lunging and thrusting while using the left hand to

parry and trap. It’s really not a difficult weapon to practice

(as one master even said) once you have grasped the simple foundation

of its method. It just takes time and sufficient effort. The

seemingly complicated exchanges of rapid thrust and counter thrust

of foyning fence can appear highly technical and indecipherable

to the uninitiated beginner, but there really are only a few movements

at work.

If

you have never practiced any form of swordplay, it can be very

useful to learn modern styles of foyning fence with foil and epee,

as it is a descendant of the rapier. But be aware at all times

that these are very stylized forms of duelling sport far removed

from Renaissance martial arts. They are taught and practiced with

a number of artificial rules, limitations, and restrictions that

have nothing whatsoever to do with the combat effectiveness or

history of how earlier swords were actually used. The polite ritual

swordplay of late 19th century duelling was a far cry

from the savage ferocity of Medieval and Renaissance hand-to-hand

combat. While there are core movements common between them (and

between most all forms of swordplay), the differences in the weapons

and the conditions they were used under are important.

If

you have never practiced any form of swordplay, it can be very

useful to learn modern styles of foyning fence with foil and epee,

as it is a descendant of the rapier. But be aware at all times

that these are very stylized forms of duelling sport far removed

from Renaissance martial arts. They are taught and practiced with

a number of artificial rules, limitations, and restrictions that

have nothing whatsoever to do with the combat effectiveness or

history of how earlier swords were actually used. The polite ritual

swordplay of late 19th century duelling was a far cry

from the savage ferocity of Medieval and Renaissance hand-to-hand

combat. While there are core movements common between them (and

between most all forms of swordplay), the differences in the weapons

and the conditions they were used under are important.

Where can someone learn more about real rapiers and rapier fencing?

There

are unfortunately still very few reliable sources for learning

about real rapiers and real Renaissance fencing. My advice is

to follow along with the articles on the ARMA website and read

the books on our reading list and, of course, consider becoming

a member. Also, pay attention to everything you can and collect

your own study notes. But, be always wary of its accuracy. When

it comes to rapiers (and other swords), popular conceptions in

general are considerably different than both the historical and

the physical reality. In my experience, it’s

often difficult for some people (whose knowledge of swords and

swordsmanship primarily comes from movies, TV, video games, and

comic books) to put aside their preconceptions and instead, consider

the reality of the historical record when forming their opinions.

What

is worse, however, is that some modern fencing teachers will intentionally

put forth known falsehoods concerning the rapier as a way of camouflaging

their ignorance of fighting arts from the Renaissance era and

their own virtual irrelevance to its study. So, read a lot, study

hard, but be cautious about what information you accept as correct.

As with many things, when learning either history or fencing,

skepticism is healthy.

There

are unfortunately still very few reliable sources for learning

about real rapiers and real Renaissance fencing. My advice is

to follow along with the articles on the ARMA website and read

the books on our reading list and, of course, consider becoming

a member. Also, pay attention to everything you can and collect

your own study notes. But, be always wary of its accuracy. When

it comes to rapiers (and other swords), popular conceptions in

general are considerably different than both the historical and

the physical reality. In my experience, it’s

often difficult for some people (whose knowledge of swords and

swordsmanship primarily comes from movies, TV, video games, and

comic books) to put aside their preconceptions and instead, consider

the reality of the historical record when forming their opinions.

What

is worse, however, is that some modern fencing teachers will intentionally

put forth known falsehoods concerning the rapier as a way of camouflaging

their ignorance of fighting arts from the Renaissance era and

their own virtual irrelevance to its study. So, read a lot, study

hard, but be cautious about what information you accept as correct.

As with many things, when learning either history or fencing,

skepticism is healthy.

Rapier fencing is neither difficult nor complex. It existed not on its own but within a larger context of Renaissance arms and armor and fighting skills. Only the later Baroque smallsword and modern fencing made foyning fence into something elaborate. Beware of modern teachers of the rapier who, as neither high-caliber fighters with long training in Renaissance combatives nor highly skilled martial artists, go out of their way to promote the mystique of the rapier rather than its practical simplicity.

Why does historical accuracy matter when studying the rapier?

Because

the rapier was a real weapon invented by real people to really

fight one another, we owe it to their legacy and our heritage

to respect the history involved. History is about what actually

took place, not some imaginary or pretend things. It presents

for us the record of the ideas, the events, and the people that

formed our world. It is not merely a starting point of inspiration

for fantasy entertainment and role-playing amusement. History

really happened.

Because

the rapier was a real weapon invented by real people to really

fight one another, we owe it to their legacy and our heritage

to respect the history involved. History is about what actually

took place, not some imaginary or pretend things. It presents

for us the record of the ideas, the events, and the people that

formed our world. It is not merely a starting point of inspiration

for fantasy entertainment and role-playing amusement. History

really happened.

There is nothing imaginary that can compare to

the reality of the millions of our ancestors having over centuries

lived out their lives, working, playing, loving, creating, thinking,

fighting, and dying. Their efforts and ingenuity, their sweat

and blood, their continuous life and death trial and error testing

are our sole best source for what truly worked in personal combat.

They learned from earnest experience. They knew what worked and

what didn’t because their lives depended on it. It was real.

Rather than just make things up now or mix things together today

we owe it to both our forebears and our descendants to appreciate

their world and the struggles that created it. To best understand

the present and prepare for the future, we must consider the past.

Because to know where you’re going, you have to know where you’re

from. Whatever the motive for your interest in swords and swordplay,

it must begin with a firm appreciation of the history behind when

and where and why they existed.

The preceding has been excerpted from a forthcoming book on Renaissance swords. Please note this article is protected by copyright. To use, quote, copy, or reproduce any part of it for a school project or website you must contact us for permission first.

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||