Editorial

The Contextual Dilemma of Learning Self-Defense The Contextual Dilemma of Learning Self-Defense

By

John Clements

ARMA Director

I came across an article where a philosophy professor and martial artist

was complaining about two professional martial arts instructors conversing

over street violence and self-defense in a podcast. In their talk, they

discussed how virtually anybody you’re going to come across today has

some sort of martial sport training, and that rather than fighting it

out when threatened with physical assault, running away is often the first

best option. The author thought that the other two were doing a tremendous

disservice to potential students and their listeners. More or less, by

stressing the function of martial arts originating as war skills —or as

we know it, the Arts of Mars— the author argued that self-defense students

must learn to confidently deal with the inherent fear of violent confrontation,

and that conveying this crucial lesson first and foremost is the primary

role of a good martial arts instructor. He more or less contended that

teaching students to just run away is telling them to give in to fearfulness.

Making the student afraid over how dangerous everything out there is only

serves to make them frightened, timid, and therefore weak and possibly

more vulnerable —the very antithesis of what competent martial arts instruction

is supposed to provide.

If you have no fighting skills, then you have no option but to try to

flee. By contrast, having those skills does not just give you the option

of fighting effectively, they give you the chance of winning when fleeing

is not an option. Yes, you should learn to be aware of your environment

and surroundings and appraise possible threats, but that doesn’t mean

instantly attempting to flee in fear over every perceived danger (not

to mention that displaying weakness in response to aggression never deters

it).

I do understand where he’s coming from, because when you try to convey

to students the reality of violence, whether historical or modern, it

can often be quite disturbing and overwhelming for a certain portion of

them. It can be quite discouraging to some when they begin to be cognitive

of just how vulnerable they really are and how much effort is required

to viably defend themselves in most all life-threatening encounters. This

is especially true for female students, younger students, elderly students,

and physically less capable students. The necessity of developing a certain

martial spirit is therefore crucial. And this was expressed eloquently

by Master Fiore, who at the dawn of the 15th century first warned that

if you do not have audacity, do not study the Art of Defence. Decades

earlier, Master Doebringer specifically warned to never fight either in

fear or out of anger. And there are many other Renaissance fight masters

who addressed the critical factor of emotional control in having the proper

attitude to effectively employ fighting skills (as well as the ethical

component involved).

The development of this kind of mindset, this kind of martial character,

or Kampfgeist as it was then known, is the most challenging, time-consuming

and, indeed, intimate aspect of the teacher-student relationship. Many

students will bring some of this with them when they start training, particularly

if they are younger athletic males culturally wired toward things martial.

But many students do not have this discipline whatsoever. They come to

the craft with a larping attitude, sport-play mentality, or just some

abstract recreational conception oblivious to the nature of real violence.

In my experience, this truth is even more dramatically obvious in our

training precisely because we work directly with formidable weapons whose

power and ferocity are so self-evident. And yet, in lessons we typical

struggle at educating students to overcome a century of pop-culture nonsense

polluting their views of how these weapons actually function in earnest

violence—and how human beings will genuinely respond to it. This is why

in my courses I have always stressed the universal core principles at

work, and how a weapons-based system is inherently about equalizing vantages.

The lethal immediacy of weaponry, whether it be a simple baton or knife

or a historical sword for war or duel, follows underlying rules that apply

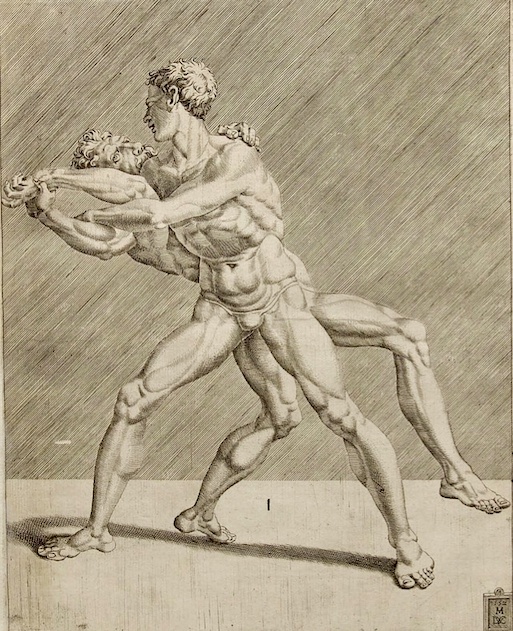

across the board (there is a reason after all why we find the same fundamentals

appearing in ancient Greek artworks, 15th century fight books, and modern

military combative programs). This is also why I put so much emphasis

on the unarmed techniques involved and never teach the craft in a vacuum

of merely “fencing” weapon against weapon.

So the author’s essential criticisms are correct in my opinion. The whole

point of the Art, taught Master Liechtenauer in 1389, is to overcome a

stronger opponent —or as Master Vadi put it in the 1480s, cunning defeats

any strength. However, Liechtenauer himself also expressed there is

no shame in running away from four or five opponents —or retreating by

“Cobb’s traverse” from an adversary too dangerous to engage without incurring

injury, as Master George Silver put it in 1598. Avoiding unnecessary danger

(as well as provocation) is itself a tremendous part of martial knowledge.

But, the author is also right that so much of today’s popular martial

arts and sports styles do not prepare the student for sudden personal

assault under either civilian or military conditions. One cannot use these

methods, especially the grapple-centric ones, in most street situations

(and certainly not against multiple assailants or hand weapons).

So, as he criticized the two professional instructors for suggesting

that most of the time in self defense it’s just best to run away, I concurred.

It takes shrewd judgment to discern when the optimal move is to withdraw,

and that decision should not be made out of fear—in the same way the decision

to fight should not be made from bravado. Liechtenauer taught that when

you understand that no one just defends except out of fear, then you understand

how to prevent attacks, adding that for those who just look and wait and

do nothing but defend it is disastrous. He added that of the defense he

would not speak, for there was nothing to be said other than if your opponent

attacks you attack, because a defensive attitude means you are already

beaten. Master Altoni observed in 1550 that defense is comprised of offense,

while the soldier-duelist Ghisliero in 1587 instructed that there is no

defense except that we offend and no offense except that we defend. The

entire concept at work was best expressed in 1610 by the Master Capo Ferro

as “offense is defense.” In this regard, just running away is ultimately

self-defeating because you can always be chased down, as George Silver

pointed out about rapier fencers invariably retreating if you kept pressing

in on them.

Yet,

a fundamental truth of self defense that the two professionals were reasonably

expressing is that to be able to act offensively, one must first also

have the tools—physical as well as mental. And there is no question that

this very often is simply not possible for most students that a fight

instructor commonly comes across today. At the same time, I think that

the element being overlooked by all these gentlemen is that martial

arts are contextual and situational. There is no universal fool-proof

system or tactical solution for all combatants on all occasions. Not every

self defense solution is optimal for everyone every time. Not every method

is fit for the aptitude of every particular type of student, just as not

every method (or weapon) is ideal for every particular encounter. The

same is true for whatever manner by which any instruction is being provided.

Each lesson will not always match the mindset of every type of practitioner.

Pragmatic as any fighting system must be, in responding to the chaos of

close combat it nonetheless is as Master Nicoletto Giganti observed in

1606, “a speculative science.” The only constant at work in any of

this is human nature itself. Yet,

a fundamental truth of self defense that the two professionals were reasonably

expressing is that to be able to act offensively, one must first also

have the tools—physical as well as mental. And there is no question that

this very often is simply not possible for most students that a fight

instructor commonly comes across today. At the same time, I think that

the element being overlooked by all these gentlemen is that martial

arts are contextual and situational. There is no universal fool-proof

system or tactical solution for all combatants on all occasions. Not every

self defense solution is optimal for everyone every time. Not every method

is fit for the aptitude of every particular type of student, just as not

every method (or weapon) is ideal for every particular encounter. The

same is true for whatever manner by which any instruction is being provided.

Each lesson will not always match the mindset of every type of practitioner.

Pragmatic as any fighting system must be, in responding to the chaos of

close combat it nonetheless is as Master Nicoletto Giganti observed in

1606, “a speculative science.” The only constant at work in any of

this is human nature itself.

Master Meyer wrote in 1570 that everyone is built differently, therefore

everyone fights differently, and everyone thinks differently, therefore

everyone fights differently, but all must attest that all fighting skill

derives from the same common principles. This truth is exactly why there

are so many different styles and theories, and indeed, diverse weapons,

throughout history around the globe. As a student you must learn which

method and approach is appropriate for you—for your physical and mental

dispositions. And as a teacher, you must help the student find it. Or

as the master François Dancie expressed in 1623, a good teacher must strive

to match the Art to the individual student’s needs and nature.

All of this presents a certain dilemma and is exactly why the wisdom

of the Renaissance Masters of Defence preserved in volumes of their remarkably

well-developed fighting systems is still so extraordinarily valuable.

Devoid of the civilianization, theatricalization, commercialization, and

hyperbolization which plagues so many self defense styles now (modern

and traditional), their teachings on the Noble Science hold tremendous

value for us in how they speak to us now. As I’ve expressed many times:

Everything in martial arts is about defence, except for defence, which

is about offence.

2-2022

|