|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

by Jeffrey Hull

It is possible that

Talhoffer’s longsword plates (tafeln)

are showing us both kinds of fighting.

Unfortunately he does not tell us one way or the other. His unarmoured longsword fighters are

ostensibly practicing unarmoured fighting – yet demonstrably, they are

practicing both unarmoured fighting and armoured fighting. This is realised if we consider how the

portrayed moves relate to the variety of combat techniques as dependant upon

whether a Medieval combatant fought either unarmoured or armoured. If so, then we find the longsword plates

dealt and grouped ordinally and equally into thirty-six for unarmoured and

thirty-six for armoured. It seems that there are

seventy-two plates (#01-#67 & #74-#78) delineated for longsword (Langes Schwert) from the fight-book of

1467 AD by Hans Talhoffer which consist of half (#01-#36) meant for

unarmoured fighting (bloßfechten) and half (#37-#67 & #74-#78)

meant for armoured fighting (harnischfechten). This sequence of longsword plates is

interposed by six plates (#68-#73) dealing with a grudge-match between two

knights in full plate-armour (rüstung) who also wield longswords.

Incidentally, all men portrayed in the range of plates from #01-#78

are fighting afoot. Firstly, we should consider

the weaponry shown in the plates delineated for longsword. The fighters seem to wield Oakeshott-type

XVa, XVIa or XVIIIa longswords. Such

were a basic selection of differing yet coeval types for middle to late 15th

CentAD throughout Germany and Austria, or for that matter, much of the rest

of coeval Europe. Secondly, we should

consider the garments shown in the plates delineated for longsword. The fighters are outfitted in some sort of

close-fitting fight-clothing, tailored for the whole body and paneled,

gusseted or padded. If these were

undergarments for rüstung, then

such would have served to absorb shock beneath the custom-fit tempered steel

plating which covered a knight’s whole body – in other words,

arming-clothes. However it be, this

clothing must have served as sweat-suits, for we can plainly see the fighters

practicing thusly garbed. Such male

costume was common enough throughout much of Europe at that time and consists

of doublet, shirt, trews, cod and shoes.

This fight-clothing could have been made of any variety of textile

and/or tanned materials, such as linen, wool, hemp, silk or leather, with

perhaps a certain part of metal.

Perhaps it has been too generally and readily assumed in modern times

that fighters bedecked in this manner were always portraying primarily

unarmoured fighting. Thirdly, we should consider

the relevant techniques portrayed and described by the master. As shall be explained, some are fit for

doing certain things better than others.

Hence, some tend to be used more for unarmoured and some more for

armoured. These techniques are as

follows: Hewing –

this is cleaving with the edge. Talhoffer calls various techniques done by this method: schlachen; schlag; haw;

how; hout; krump; gayszlen

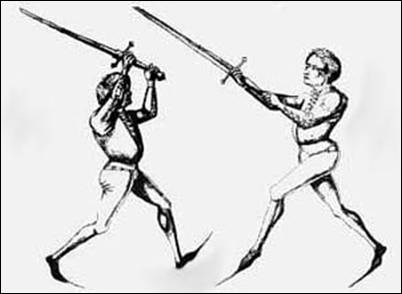

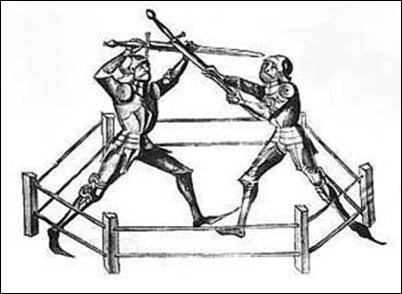

Hewing – from plate #01. Oberhow.

– Vnderhow. Overhew.

– Underhew. Thrusting – this is piercing

with the point or ramming with the pommel. Talhoffer calls various techniques done by this method: ortt; stich; hefften; stos; stossen [different

from hinweg stossen or shoving]

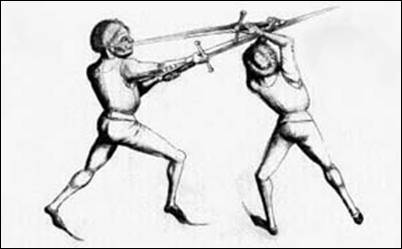

Thrusting – from plate

#04. Das

lang Zorn ortt. – Darfür ist das geschrenckt ortt. The

long wrath-point. – Therefor is the set-point. Slashing – this is raking with

the edge. Talhoffer calls various techniques done by this method: schnit; fahen [!]

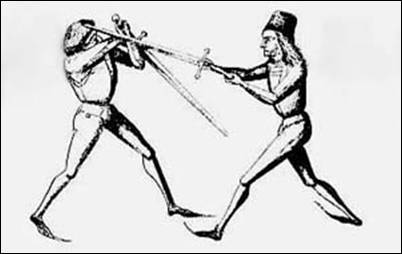

Slashing – from plate #21. Der

gryfft nach der vnderen blosz. – Der schnit von oben daryn. He

attacks at the lower openings. – He slashes from above therein. Half-swording – This is when one

hand grips the hilt and the other hand grips the blade. Talhoffer calls various techniques done by this method: brentshiren; gewauppet ort Morte-striking – This is when both

hands grip the blade to smite with the pommel or crossguard. Talhoffer calls various techniques done by this method: mortschlag; mordstreich; tunrschlag

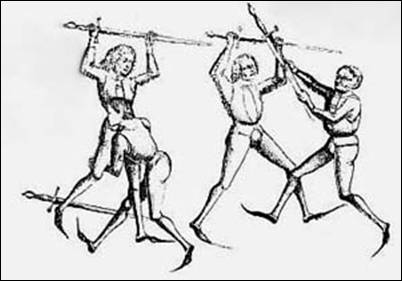

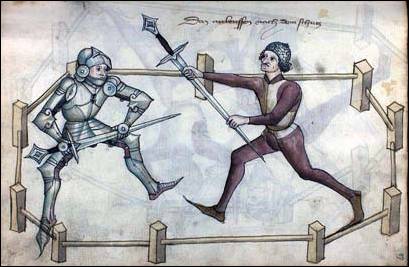

Half-swording against

Morte-striking – from plate #37 (2nd pair). Vsz

dem Tunrschlag Ain werffen. – Vsz dem Tunrschlag ain Ryszen. Out

of the thunder-strike throwing. – Out of the thunderstrike wrenching. Lastly, we should consider the

differences between unarmoured and armoured fighting of that time. However, it is acknowledged that much

similarity unavoidably exists as we are talking about the same weapon – the

European longsword of 15th CentAD.

Yet the distinctions are clear and should be of general agreement

among those who practice historically realistic European swordfighting which

is based upon the German fight-books (fechtbücher) or upon the Italian manuals. What follows is substantiated by perusing

such fight-books as Liechtenauer (1389 via Doebringer and 1440 via Ringeck),

Liberi (1410), Gladiatoria

(1430-1444), Lignitzer (1452 via Danzig), Hundfeld (1452 via Danzig &

1491 via Speyer), Talhoffer (1467), Wallerstein

(1470), Vadi (1482), Lew (1491 via Speyer), Goliath (1510), Czynner (1538) and Mair (1550): * Hewing and slashing are most wieldy for unarmoured* The blade of a longsword wielded by hew or

slash is effective against the unarmoured foe, or by hew for breaching the

leather or maille-armoured foe – yet neither does well against the

plate-armoured foe. Against such the

hew may batter yet probably shall not breach.

And the slash is next to worthless.

Against plate-armour such strikes shall most likely simply bounce,

glance or slide. Hewing must have

proven frighteningly destructive against the unarmoured foe, or for that

matter, the maille-armoured foe – as everything from battlefield archaeology

to modern test-cutting on deer carcass shows – yet it just was not the thing

for hurting the plate-armoured foe. * Half-swording and morte-striking are best for armoured* An unarmoured fighter can do both as needed,

either against an unarmoured foe or especially against a plate-armoured

foe. A longsword wielded by

half-swording lets the fighter strongly set aside a foe’s strike and allows

accuracy and power for thrusting, especially for seeking the gaps of

plate-armour. If wielded to

morte-strike, it makes for a fearsome attack against a foe whether unarmoured

or armoured. With the pommel it allows

battering of plate-armour; and with the crossguard, it allows piercing of its

gaps or perhaps the armour itself, and hooking and wrenching of both his

armour and the foe himself. The

equally plate-armoured fighter and foe would surely do both half-swording and

morte-striking against each other. * Thrusting is ubiquitous to

both armoured and unarmoured* The point of a longsword wielded this way has overall efficacy, utilised

to smite the unarmoured foe almost anywhere and to smite the armoured foe by

breaching the gaps of his plate-armour.

Thrusts can be driven with hands upon hilt or by half-swording. * Arms crossed or apart works for unarmoured * yet * Arms apart works for armoured * When warding or attacking with

the longsword, a man in fight-clothing can work easily with techniques that

either make his arms cross or keep them apart – however, the man in

plate-armour really must tend to keep his arms apart when warding or

attacking, for his steely shell hinders or prevents such with arms crossed (geschrenckt). One may note that the knights in rüstung keep their arms apart in their

fight. Now, with all this in mind,

a simple analysis of Talhoffer’s captions and pictures finds marked

difference between what prove to be two distinct halves of Talhoffer’s

longsword plates:

So the distinction seems

rather clear. The first half has lots

of hewing and a bit of slashing, whereas the second half has neither

thereof. The first half has little of

half-swording and morte-strikes, whereas the second half has lots of each

comparatively. Each half has decent if

differing amounts of thrusting. The

first half portrays a noticeable amount of arms-crossed yet mostly

arms-apart, whereas the second half only portrays arms-apart. Hence Talhoffer’s fight-clothing-bedecked

longswordsmen portray a definite unarmoured first half and a definite

armoured second half for their totality of longsword fighting

techniques. None of this should be any

surprise if we simply realise that it would be utilitarian, efficient, and

couth for the students of a fight-school to practice differing sets of

contextually dependant moves for a given weapon just as they would practice

differing weaponry. Furthermore, besides the foregoing technical and statistical evidence,

it seems there is also numerological evidence. Talhoffer’s #73 rüstung plate portrays the exact same

struggle of weaponed-point (gewauppet ort) against morte-strike (Mordtschlag), as found in the second pair within his #37 langes schwert plate of weaponed-point

(unnamed) against thunder-stroke (Tunrschlag)

– but with differing outcomes. In the rüstung, weaponed-point-man forsets (versetzen or versatzung) morte-man’s attack and finishes by shoving him away (hinweg stossen) – whereas in the langes schwert, thunder-man wrenches (Ryszen) weaponed-point-man’s attack

and finishes with thrust of pommel (stos)

to face. Thus the rüstung plates end with similar struggle as the beginning of the harnisch half of the langes schwert plates. If this was done wittingly by the arcanity

of Medieval numerology, then perhaps it is indicated by how switching the

digits of “37” makes “73” and vice-versa.

Such thinking may explain the odd placement of the six rüstung plates within the seventy-two langes schwert plates between #67

& #74 rather than between #36 & #37 – that is, between the end of the

bloß and the beginning of the harnisch. Indeed, the knights struggle within a

battle-yard (schranken) which is

fenced hexagonally, thus reinforcing the idea of the factor of “6”, which if

squared arrives at “36” – a familiar number as already witnessed.

The same Half-swording

versus Morte-striking – from plate #73. Usz

der versatzung hinweg stossen. – Der haut den straich volbracht. Out

of forsetting shoving away. – He has fully brought the strike. Lastly,

Talhoffer’s 1459 version contains a plate (87 recto) portraying a combatant in full plate-armour versus one

in fight-clothing. This plate is set

in the fight-book such that it bridges its own sections of rüstung and langes schwert – that is, betwixt fighters portraying harnisch and bloß. Indeed, these

combatants are portrayed within a battle-yard doing half-swording versus

morte-strike. The similarity is

interesting to consider vis-à-vis

Talhoffer’s last edition.

Guess what happens here –

from 87 recto of the 1459. Das anlouffen nach dem

schutz. The ready-stance after the

spear-hurling. One final

thought: Since Talhoffer’s readership

were likely the knights and soldiers of his lord, Herr Leutold von Königsegg,

it makes sense that such men would have need to know the variance

distinguishing bloß from harnisch – thus the emphasis of

technique befitting different combat. Conclusion: The longsword plates found in Hans

Talhoffer’s fight-book of 1467 AD are dealt into two equal halves which show

the typical and marked differences between armoured fighting and unarmoured

fighting of 15th CentAD European swordsmanship. ***** Primary Sources: Cod.icon. 394a Handschrift; Hans Talhoffer (auth); Schwaben; 1467; Bayerische

Staatsbibliothek; München Fechtbuch

aus dem Jahre 1467;

Hans Talhoffer (auth); 1467; Michael Rasmusson (transcr & transl); 2004;

Schielhau Web-Site; <http://www.schielhau.org/tal.html> Medieval Combat; Mark Rector

(transl & interp); Hans

Talhoffer (auth); Bayern; 1467; Greenhill Books; London; 2000 Meister Hans Thalhofer: Alte Armatur und Ringkunst; Hans Talhoffer

(auth); Thott 290 2º; Bayern; 1459;

;

<www.kb.dk/kb/dept/nbo/ha/index-en.htm> Talhoffers Fechtbuch aus dem

Jahre 1467; Hans Talhoffer (auth);

Schwaben; 1467; Gustav Hergsell (transcr & transl); Prague; 1887; Forschungs und Landesbibliothek Gotha Buch 4° 113/2 Talhoffers Fechtbuch aus dem

Jahre 1467; Hans Talhoffer

(auth); 1467; Mark Rector (transcr & transl); 1999; ARMA Web-Site;

<http://www.thearma.org/Manuals/talhoffer.htm> Secondary Sources: Altenn Fechter anfengliche Kunst; Christian Egenolph (auth); Alexander

Kiermaier (transcr); Franckfurt am Meyn; 1529; Die Freifechter Webseite; 2001; <www.freifechter.org> Armour from the Battle of Wisby; Bengt Thordeman (auth); Brian Price (intro);

Chivalry Bookshelf; Highland Village; 2001 Blood Red Roses: The Archaeology of a Mass Grave

from the Battle of Towton AD 1461;

Veronica Fiorato (edit), Anthea Boylston (edit), Christopher Knüsel (edit);

Oxbow Books; Oxford & Oakville; 2000 Brief Introduction to Armoured Longsword Combat; Matt Anderson (auth); Shane Smith (auth); ARMA

Web-Site; 2004; <www.thearma.org/essays/armoredlongsword.html> Codex

Wallerstein; Gregorz

Zabinski (transcr & transl); Bartlomiej Walczak (transl & interp);

Paladin Press; Boulder; 2002 (from 1470) Flos

Duellatorum; Fiore dei

Liberi (auth); Hermes

Michelini (transl); Italy; 1410; Knights of the Wild Rose; Calgary; 2001;

<www.varmouries.com/wildrose/fiore/fiore.html> Gotha Buch

4° 113/2 Handschrift; Hans Talhoffer (auth);

1467; Forschungs und Landesbibliothek

Gotha History

of Art; HW Janson;

Prentice-Hall & Abrams; New York; 1981 (2nd edit) Kurzen Schwert; Martin Hundfeld

(auth); from Codex Speyer (Handschrift M

I 29 or Fechtbuch);

Hans von Speyer (edit & comp); Beatrix Koll (transcr); (transcript

thereof & formerly also facsimile); Almania; 1491; Universitätsbibliothek Salzburg;

2002; <www.ubs.sbg.ac.at/sosa/webseite/fechtbuch.htm> Kurzes Schwert; Andre Lignitzer (auth); Kurzes Schwert; Martein Hundtfeltz

(auth); both from Danzig Fechtbuch; Peter von Danzig (auth & edit); Monika Maziarz (transcr); Preuszen; 1452; ARMA-Poland Web-Site; 2004; <www.arma.lh.pl/index.html> Liber

Chronicarum; Schedel; Wolgemut; Pleyenwurff; Alt;

Koberger; Füssel; Nürnberg; 1493; bound uncoluored Latin edition; Wilson

Collection; Multnomah County Library Liber de Arte Gladiatoria

Dimicandi ; Filipo Vadi (auth); Urbino; 1482; Luca

Porzio (transl); ARMA Web-Site; 2002; <http://www.thearma.org/Manuals/Vadi.htm> Medieval Meat Cutters; James Knowles (prod-direct); ARMA-Ogden Web-Site;

Quicktime-video; Utah; 2004;

<http://www.arma-ogden.org/content/view/11/2/> Records of the Medieval Sword; Ewart Oakeshott (auth & illus); Boydell Press;

Woodbridge; 2002 (rev-ed) Ritterlich Kunst; Sigmund Ringeck (auth); Johannes Liechtenauer (auth); Stefan Dieke (transcr); Mscr. Drsd. C 487; Bayern; 1389

& 1440; Sächsische

Landesbibliothek-Dresden; Die

Freifechter Webseite; 2001;

<www.freifechter.org> Sigmund

Ringeck’s Knightly Art of the Longsword; David Lindholm (transl & interp); Peter Svärd (illus); Johnsson & Strid (contr); Sigmund

Ringeck (auth); Johannes Liechtenauer (auth); Paladin Press; Boulder; 2003

(from 1389 & 1440) The

Tailoring of the Grande Assiette; Tasha Kelly McGann (auth); La Cotte Simple Web-Site; 2004;

<www.cottesimple.com/blois_and_sleeves/grande_assiette/grande_assiette_overview.htm> The Wars of the Roses; Terrence Wise (auth); Gerry Embleton (illus); Osprey;

Oxford; 2000 ***** Acknowledgements:

My thanks to Matt Anderson, Casper Bradak, Donald Lepping, Randall

Pleasant, Shane Smith, and Bartholomew Walczak. About the

Author: Jeffrey Hull has been training

in European fighting arts the ARMA way for about five years now. Previously he trained in Asian martial

arts. He holds a BA in Humanities. Copyright 2005 of

Jeffrey Hull |

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||