The

Centrality of the Longsword

The

Centrality of the Longsword

in the Study of Renaissance Martial Arts

“there is only one Art of the sword” it is “the basis and a core of all the arts of fighting.”

- Master Johannes Liechtenauer, 1389

By John Clements

Why the longsword?

– This is a question I have often asked myself and one which many

students of this craft has also asked of me over the years. Personally, I have

always favored the double-hand sword. The symmetry of a long, straight,

two-edged blade with cross-guard has a formidable elegance all its own. Though

I grew up playing "sword and shield" then got into modern "foyning" fence and,

as most adolescents do, for a time became fascinated with the katana, the later

discovery that there was a systematic historical method to using the European

longsword became the real revelation.

Even as I readily adore training with all manner of Medieval and

Renaissance weaponry, and particularly the rapier as well as sword &

dagger, for me the longsword has held a special place. I have long felt this was the case

historically as well. Recently, the centrality

of the longsword to the Renaissance arts of fighting

has become even more apparent.

No other historical hand-weapon was arguably as resourceful

as the longsword. It possesses a versatility suited to battlefield,

single-combat, or common-defense against the widest array of arms and armor.

The longsword could be manipulated as spear and war-hammer as well as

short-sword. Whether as warsword, bastard-sword, spadone,

estoc, Schlachterschwerter, or greatsword, I have come to see the double-handed straight sword as containing

within its practice nearly everything that is found in other weapons. Its core

basis is identical to that for using so many others, be it dagger, spear,

polaxe, or short side-sword. Extensive study of this weapon has convinced me

that practice in it provides the greatest foundation for understanding the diverse

teachings of Renaissance martial arts, from unarmed grappling to sword &

buckler and even the rapier.

No other historical hand-weapon was arguably as resourceful

as the longsword. It possesses a versatility suited to battlefield,

single-combat, or common-defense against the widest array of arms and armor.

The longsword could be manipulated as spear and war-hammer as well as

short-sword. Whether as warsword, bastard-sword, spadone,

estoc, Schlachterschwerter, or greatsword, I have come to see the double-handed straight sword as containing

within its practice nearly everything that is found in other weapons. Its core

basis is identical to that for using so many others, be it dagger, spear,

polaxe, or short side-sword. Extensive study of this weapon has convinced me

that practice in it provides the greatest foundation for understanding the diverse

teachings of Renaissance martial arts, from unarmed grappling to sword &

buckler and even the rapier.

Background & Context

There is no question that the largest pool of surviving

instructional literature on pre-Baroque European fencing concerns the use of

different forms of late-Medieval double-handed sword. The longsword dominated

the literature on unarmored and armored foot combat for more than 200 years.

From the mid-1300s (and into the early-1600s) the weapon was the focus of

considerable exploration until the ascendance of the rapier in the face of new

military technology and changing civilian self-defense conditions during the

mid-1500s.

Instructional material on the longsword makes up an

extensive component of Renaissance martial arts teachings. We need only consider the foundational

writings on Johannes Liechtenauer's method beginning in 1389, the important

work of Fiore Dei Liberi from 1410, through the voluminous contributions of

many 15th century Fechtmiesters that followed, up to Fillipo Vadi in

the 1480s, and Pietro Monte by 1500, to a host of anonymous works and rewritten

teachings into the mid-16th century. One of the final expressions of

its teachings culminated in the published treatise of Joachim Meyer in 1570.

Instructional material on the longsword makes up an

extensive component of Renaissance martial arts teachings. We need only consider the foundational

writings on Johannes Liechtenauer's method beginning in 1389, the important

work of Fiore Dei Liberi from 1410, through the voluminous contributions of

many 15th century Fechtmiesters that followed, up to Fillipo Vadi in

the 1480s, and Pietro Monte by 1500, to a host of anonymous works and rewritten

teachings into the mid-16th century. One of the final expressions of

its teachings culminated in the published treatise of Joachim Meyer in 1570.

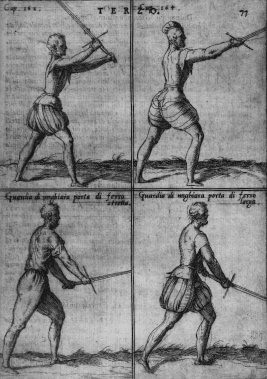

When we think of swordplay in the Renaissance the slender

thrusting sword, or rapier, almost immediately comes to mind as the

representative weapon of the Age. It is the basic techniques of the single-hand

rapier that survives today in its post-Baroque descendants of modern sport

fencing. Yet, when considered separately from its earlier cut-and-thrust cousin

(the military side-sword of the early 16th century) the true rapier

had a narrower and more specialized self-defense role. Even during its highest

period of popularity in the early 17th century, it remained one of

many swords types contemporary with more traditional military cutting blades and

common polearms. The martial conditions of which these slender thursting swords were employed and

the challenges they were called upon to face had also both changed considerably over

that which earlier had once necessitated the development of the earlier longsword. When we deliberate on the true rapier,

its origin as a civilian weapon of street-fighting and its later incarnation as

the dueling weapon par excellence among the aristocracy, its place within Reniassance combatives was not a

central one considering the totality of fighting arts in the era.

Indeed, for the fighting method of this slender thrusting

sword, the true rapier is found in less

than a dozen instructional texts from the middle of the 1500s to the middle of

the 1600s (e.g., Lovino, Ghisliero, Heredia, Narvaez, Saviolo, Fabris, Swetnam,

Hale, Giganti, Capo Ferro, Alfieri, etc.)

Even then, the authors of several of these important works often still

included material on older short swords or back-swords as well as polearms or

even the two-handed greatsword.

Indeed, for the fighting method of this slender thrusting

sword, the true rapier is found in less

than a dozen instructional texts from the middle of the 1500s to the middle of

the 1600s (e.g., Lovino, Ghisliero, Heredia, Narvaez, Saviolo, Fabris, Swetnam,

Hale, Giganti, Capo Ferro, Alfieri, etc.)

Even then, the authors of several of these important works often still

included material on older short swords or back-swords as well as polearms or

even the two-handed greatsword.

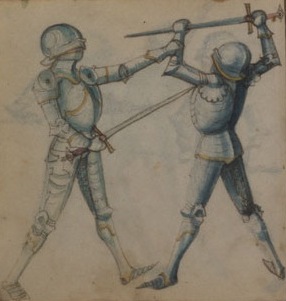

More so than any other single weapon the fearsome longsword,

with its utility, versatility, and inherent use of half-gripping the blade and

close-in body-to-body action, embodies the knightly Art of Combat. By contrast, the later rapier, though it developed

from earlier tapering single-hand swords, was specialized more to unarmored private

duelling. It was really only when military conditions began to change and

armored faded in the face of firearms, that the longsword became impractical

for civilian security and "cavalier" affairs of honor, as well as unnecessary

for general war.

What Role in the Art of Defence?

What Role in the Art of Defence?

What was it then about the use of longer double-handed

blades that earlier attracted so much focus from fighting men and fencing

masters? What was it about this

weapon that they considered it with such apparent regard? What was it that compelled them to give

it so much attention over (presumably) more common single-hand swords which

were their contemporaries as well as predated them? Why was so much instructional material devoted to the long

double-handed sword rather than to single-handed versions or pole-arms? The

answer to the question of the longsword primacy is its popularity was no matter

of some mere knightly symbolism but a direct factor of its pragmatic utility.

Of the longsword, the grandmaster Johannes Liechtenauer in

the late 14th

century taught, "there is only one Art of the sword"

and it is the "basis and a core of all the arts of fighting." In

his

later fighting treatise of 1570, the master Joachim Meyer wrote how the

weapon, "is celebrated among other weapons for artfulness and

manliness, and because of

it I have what's needed for good understanding from which to make

progress, and

thus quickly see with clarity how with wise handling all this can be

applied in

other arts and disciplines." Of his tapered double-edged spada a doy mane

or “two-hand sword,” the

master Fiore dei Liberi in 1410 declared it “mortal against any weapon”

adding that it: "fights near or far, closes in for disarms and

wrestling, can break and bind, cover and injure, and is a royal weapon,

the maintainer of justice used to increase goodness and destroy

malice."

[Getty 25r].

Of the longsword, the grandmaster Johannes Liechtenauer in

the late 14th

century taught, "there is only one Art of the sword"

and it is the "basis and a core of all the arts of fighting." In

his

later fighting treatise of 1570, the master Joachim Meyer wrote how the

weapon, "is celebrated among other weapons for artfulness and

manliness, and because of

it I have what's needed for good understanding from which to make

progress, and

thus quickly see with clarity how with wise handling all this can be

applied in

other arts and disciplines." Of his tapered double-edged spada a doy mane

or “two-hand sword,” the

master Fiore dei Liberi in 1410 declared it “mortal against any weapon”

adding that it: "fights near or far, closes in for disarms and

wrestling, can break and bind, cover and injure, and is a royal weapon,

the maintainer of justice used to increase goodness and destroy

malice."

[Getty 25r].

The weapon may have been less numerous in warfare than

simple (and cheaper) polearms wielded by common infantry, but there is no

mistaking that by the 1300s all social classes employed swords, including the

double-handed version.

The ease by

which the longsword transitions from one-handed to two-hand techniques, between

cuts and thrusts and slices, and shifts between half-swording and

full-gripping, gives it an unprecedented versatility. Simply put, there are

blows and cutting strikes performed in a certain way with a two-handed weapon

that are not performed with a single-hand one.

There are things you do with a cutting and

thrusting blade---whether armored or unarmored on foot or

mounted---that you do not do with a trusting-only sword in one hand

(nor even with a

shafted pole-arm held in two). The left hand is also free to do things

that

cannot be done with a shield or another weapon held in the second hand,

while

half-swording provides flexible options that are not as available to

shorter

weapons. Whether for war, duel, or common self-protection the weapon

proved

itself in diverse conditions. It is no wonder it served as such a sound

basis

for learning how to fight.

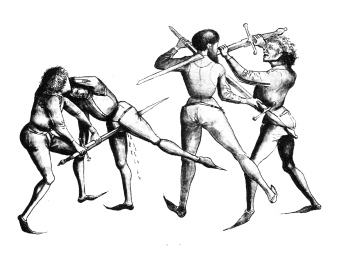

The nature of armed close-combat is such that fighting with

the longsword cannot be properly practiced without learning the basics of

timing, range, blade pressure and body leverage. These key elements cannot be

skipped in order to move onto "other aspects" of the Art. They are its core

essence and until a student acquires these fundamentals, the nature of the real

Art will continue to elude them. Wielding this weapon properly is about so much

more than holding stances and making assorted strikes or parries. Beyond cutting, slicing,

or thrusting, a good deal of this skill involved closing-in to bind and seize

the opponent—knocking, disarming, or throwing them. When training with a

longsword is approached correctly these elements are encountered at once and

acquired very quickly by the student. While at the same time, it also becomes

clear that the weapon is not about simplistic parrying and riposting while just

warding and stepping in and out of timing and range.

The nature of armed close-combat is such that fighting with

the longsword cannot be properly practiced without learning the basics of

timing, range, blade pressure and body leverage. These key elements cannot be

skipped in order to move onto "other aspects" of the Art. They are its core

essence and until a student acquires these fundamentals, the nature of the real

Art will continue to elude them. Wielding this weapon properly is about so much

more than holding stances and making assorted strikes or parries. Beyond cutting, slicing,

or thrusting, a good deal of this skill involved closing-in to bind and seize

the opponent—knocking, disarming, or throwing them. When training with a

longsword is approached correctly these elements are encountered at once and

acquired very quickly by the student. While at the same time, it also becomes

clear that the weapon is not about simplistic parrying and riposting while just

warding and stepping in and out of timing and range.

Beyond Both Cutting or Thrusting

There is a self-evident urgency to training with weapons.

They contain an immediacy of threat over that found in grappling or wrestling.

Weapons have been called the great equalizers, for it is their lethality that

gives them precedent over unarmed combat. In the historical training of

warriors there is a simple truth: arms inherently require unarmed skills, but

unarmed skills do not inherently require armed training. No historical warrior could be

effective in battle or duel if he had just studied in unarmed skills alone.

Armed and unarmed skills were not separated; they were integrated within the

martial arts of Renaissance Europe.

While the basis of all fighting arts can be reduced down to

the same essential principles as found in unarmed combat (leverage, timing,

range, etc.), and the source masters even tell us all fencing is based on

wrestling, it has always been armed

combat that has historically taken precedence. Fencing is not simply "armed

wrestling." It is fencing.

While the basis of all fighting arts can be reduced down to

the same essential principles as found in unarmed combat (leverage, timing,

range, etc.), and the source masters even tell us all fencing is based on

wrestling, it has always been armed

combat that has historically taken precedence. Fencing is not simply "armed

wrestling." It is fencing.

Though their actions have a common basis, the techniques that

can be used in the context of a sword fight are not identical to those of

unarmed combat. This is surely why the historical source teachings make

such a distinction between close-in actions of seizing and disarming ("or

wrestling at the sword"), and grappling and ground fighting as a subset.

Something that cannot be overlooked here is that if a

fighter has trained in grappling and wrestling then takes up the longsword,

this does not mean at all that they will be able to suddenly apply their

unarmed training to effectively wield the weapon against a skilled swordsman.

You have to learn how to integrate the tool into what is possible in a fight.

Weapons take precedent. I have

seen this repeatedly over the years.

Many senior members in the ARMA can attest to the difficulty they had

when they started out trying to use even the most basic of their unarmed skills

against a well-trained swordsman.

In

my own experience, because I never trained in any

wrestling or grappling, don't feel tactically comfortable there and

don't

consciously go to those techniques, I came (as a natural result) to

specialize more in my practice upon these earlier actions

occurring just before that range

(the disarms and trapping). But,

curiously, I acquired my unarmed close-in skills specifically through

training in the longsword. The longsword

taught me tremendously about feeling leverage and sensing pressure during any

portion or range of the fight, not just when blades are crossed. I learned to

apply my second hand and my whole body as needed even as I remained focused on

wielding my weapon. I didn't gain

any of this crucial aspect through any experience in rapier, sword &

dagger, or staff weapons.

In

my own experience, because I never trained in any

wrestling or grappling, don't feel tactically comfortable there and

don't

consciously go to those techniques, I came (as a natural result) to

specialize more in my practice upon these earlier actions

occurring just before that range

(the disarms and trapping). But,

curiously, I acquired my unarmed close-in skills specifically through

training in the longsword. The longsword

taught me tremendously about feeling leverage and sensing pressure during any

portion or range of the fight, not just when blades are crossed. I learned to

apply my second hand and my whole body as needed even as I remained focused on

wielding my weapon. I didn't gain

any of this crucial aspect through any experience in rapier, sword &

dagger, or staff weapons.

I

have no doubts that learning unarmed skills did not give me

corresponding knowledge of fighting with a weapon. In other words,

while I had previously learned how to kick and punch, and so was

comfortable fighting at close ranges, it was however through studying

the longsword that I was able to incorporate such actions when wielding

a weapon. [It must be further noted, that, at such close ranges, modern

fencing styles not only fail to instruct in basic defense against body

contact and free-hand actions, but under those conditions also coaches

to habitually perform suicidal techniques.]

Making the Longsword Central Again

Historically, schools and masters of fence from the Middle

Ages to the Renaissance did teach a variety of weapons together with

wrestling/grappling skills. Yet,

for some time they focused on the longsword (or sometimes the polaxe for

armored single-combat, and later the rapier instead of the longsword for

unarmored duel). They had to do this because their lives depended on competent

ability. Ours now do not. In our modern study we have to therefore engineer a

certain restructuring of the craft for modern practice (without reformulating a new systemization in the process!).

If you train

long-term in the longsword vigorously you will also come to an understanding of

unarmed throws and holds. The same clear connection cannot be said nearly as

much for training in unarmed skills alone. From

my experience studying and teaching this craft, I am

fully convinced that if you practice the longsword I guarantee you

learn some

wrestling moves and unarmed striking---but the reverse is not true. If

you

learn the longsword you can instantly adapt it to the single-hand sword

alone

(from which all double-hand techniques originate) as well as apply it

to using a buckler or even a larger shield. If you train in longsword

you learn elements instantly transferable

to the dagger or to the staff. But for the reverse, not nearly as much

transfers from any of those weapons alone over to techniques applicable

for

striking strongly and warding carefully with the longsword.

It is perhaps the lost

of central training in the importance of longsword that helps explain

why the

martial arts of the Renaissance faded and vanished. I suggest the very

reason

that this Art of Fighting was not already reconstructed by enthusiasts

over the last century is not because of any lack of source

material for its study,

but because of the overall loss of longsword training within modern

fencing culture itself.

It is perhaps the lost

of central training in the importance of longsword that helps explain

why the

martial arts of the Renaissance faded and vanished. I suggest the very

reason

that this Art of Fighting was not already reconstructed by enthusiasts

over the last century is not because of any lack of source

material for its study,

but because of the overall loss of longsword training within modern

fencing culture itself.

It cannot be overstated how profound a missing skill set

there is within modern fencing styles with their total lack of any

double-handed weapon, let alone any grappling component or use of the

second-hand. The disconnect between these styles and the old systems of

knightly combat was too great to be bridged through a mere similarity with the

rapier of centuries past. They were (and still are) simply unable to rely on their methods to

rediscover the forgotten Art.

It requires practice of the

longsword.

You cannot fully understand or

reconstruct this style of fencing via training in epee or saber or knife or

quarterstaff or cane. You

certainly can't understand it just by mixing wrestling and boxing with foil

fencing. None of these things provide what the longsword does in terms of a

well-rounded understanding of the core elements of close combat as a true

martial art.

|

Focus on Fencing with the Longsword

No one questions the value for the student today of practice

in multiple weapons or of the eventual specialization in a preferred weapon or

skill set. Nor is the uniqueness and deadliness of the rapier in doubt,

either. Yet, I am quite confident

it can now been established that the larger Art of historical European combatives we explore is best (and

most easily) unlocked through dedicated

training in the longsword.

Though we would not suspect it from the simplistic way the

weapon is typically mis-portrayed in popular culture, the inferior way it is

notoriously handled by stunt fencers and many other enthusiasts, the longsword

is undeniably versatile and sophisticated. Within its middle size length with

symmetrical grip it contains a larger pool of core elements integral to the

discipline of close combat skill. This is surely why it was so emphasized

historically by Masters of Defence.

Within the study of this craft we

can with confidence make certain educated generalizations about the value of

particular skills. There is no doubt of the element of grappling and wrestling

within Renaissance martial arts being integral to all weapons, and there is no

questioning the common necessity of dagger skill, nor the utility of the simple

staff as the fundamental polearm. The ability to wield a single-hand sword

alone or in conjunction with another weapon was also fundamental. But for

generations the longsword provided the central basis of study. Only when the

innovation of the rapier emerged later in a transformed self-defense

environment did this change.

For too long the true handling of this powerful tool has

gone under-appreciated and misrepresented.

As we approach a full understanding of the longsword and the Renaissance Art

of Defence, we can now better appreciate

centrality the weapon held and focus on it once again. Just as its emergence in the 14th century arguably

caused a "renaissance" in close-combat skills beyond what was being

done with spear,

axe, and short-sword and shield (buckler), so too has the longsword

today over

any other weapon spurred similar insight.

Thus, while our interest in this craft today may range from 14th

and 15th century knightly combat skills to the private fighting

methods of 16th century cavaliers, they all represent linked aspects

of the martial arts of Renaissance Europe---an Art unlocked by the longswordThe longsword is arguably the central weapon for studying RMA --- the key word here being central weapon of study.

Both Master Liechtenauer and Master Fiore do tell us unarmed skills are

the origin of fighting, yes. No one denies that. Yet, master

Liechtenauer himself states that there is only one Art of the sword and

that it is the basis of all the arts of fighting --- the longsword, not

the dagger, not the staff, not the messer, not the later rapier, and

not unarmed fighting. Other sources declare the messer to be the origin

of all swordplay --- meaning that its moves are simply the same as any

short sword (which obviously predates the double-hand sword).

But, the sword was the self-defense weapon of choice in the era and its

utility and popularity was precisely why so much source material is

devoted to it over anything else. What the unarmed component is about

as a natural foundation of martial arts is that when you reduce

fighting to its most essential essence, it is about two combatants

closing to make contact and seek leverage advantage in order to deliver

techniques. You cannot be ignorant of unarmed techniques or exclude

them out of fencing. That's all it means. But you don't learn fencing by grappling and wrestling. The clearest

confirmation that unarmed skills do not teach fencing techniques is the

self-evident fact that today expert grapplers and wrestlers by virtue

of their craft do not inherently know how to fight with weapons. A

simple of understanding of balance and leverage is achieved in

learning a small repertoire of unarmed holds, throws, and takedowns all

of which are used in fencing. When lethal weapons are involved,

however, the

martial application of such action is far from the ad hoc sporting play

of wrestling. But, the sword was the self-defense weapon of choice in the era and its

utility and popularity was precisely why so much source material is

devoted to it over anything else. What the unarmed component is about

as a natural foundation of martial arts is that when you reduce

fighting to its most essential essence, it is about two combatants

closing to make contact and seek leverage advantage in order to deliver

techniques. You cannot be ignorant of unarmed techniques or exclude

them out of fencing. That's all it means. But you don't learn fencing by grappling and wrestling. The clearest

confirmation that unarmed skills do not teach fencing techniques is the

self-evident fact that today expert grapplers and wrestlers by virtue

of their craft do not inherently know how to fight with weapons. A

simple of understanding of balance and leverage is achieved in

learning a small repertoire of unarmed holds, throws, and takedowns all

of which are used in fencing. When lethal weapons are involved,

however, the

martial application of such action is far from the ad hoc sporting play

of wrestling.

But learn to fence properly with the longsword or short-sword and

buckler and you will indeed learn about unarmed actions. Learn only

gentlemanly dueling ala the Baroque style, however, and you will end up

as the Victorians did: viewing Renaissance fighting systems as

"artless" collections of techniques using "wrestling tricks" while

lacking the "parry proper."

|

The longsword is arguably the central weapon for studying RMA --- the key word here being central weapon of study.

Both Master Liechtenauer and Master Fiore do tell us unarmed skills are

the origin of fighting, yes. No one denies that. Yet, master

Liechtenauer himself states that there is only one Art of the sword and

that it is the basis of all the arts of fighting --- the longsword, not

the dagger, not the staff, not the messer, not the later rapier, and

not unarmed fighting. Other sources declare the messer to be the origin

of all swordplay --- meaning that its moves are simply the same as any

short sword (which obviously predates the double-hand sword).

But,

the sword was the self-defense weapon of choice in the era and its

utility and popularity was precisely why so much source material is

devoted to it over anything else. What the unarmed component is about

as a natural foundation of martial arts is that when you reduce

fighting to its most essential essence, it is about two combatants

closing to make contact and seek leverage advantage in order to deliver

techniques. You cannot be ignorant of unarmed techniques or exclude

them out of fencing. That's all it means.

But you don't learn

fencing by grappling and wrestling. The clearest confirmation that

unarmed skills do not teach fencing techniques is the self-evident fact

that today expert grapplers and wrestlers by virtue of their craft do

not inherently know how to fight with weapons. A simple of

understanding of balance and leverage is achieved in

learning a small repertoire of unarmed holds, throws, and takedowns all

of which are used in fencing. When lethal weapons are involved,

however, the

martial application of such action is far from the ad hoc sporting play

of wrestling.

It was surely the immediacy of the lethality produced by weapons that

was the starkest reminder for the historical fighting man of which

skill set necessarily took precedent for self-defense. Whereas a

single blow of a weapon might very expectedly shear flesh, cleave the

skull, pierces the torso or face, and otherwise dismember, this is not

the case with an unarmed punch, kick, or throw. In contrast to the

grapples and holds of a friendly wrestling match, the instantaneous

nature of violent death in ones’ hands causes the Art of fencing to

produce a different mindset in the combatant, even during mock

combat. It is this fact that today’s student of Renaissance

martial arts, safely exploring techniques through practice bouts and

drills, should remain ever conscious of. |