Five Questions...

Several times a year the ARMA asks a set of Five

Questions on the subject of Renaissance Martial Arts and Historical Fencing to a range of

practitioner-researchers from different backgrounds and experience levels.

1.

To what would you attribute your interest in

historical swords? What has been the primary inspiration or source for your own individual

study of historical swordplay?

2.

Is there a favorite type of sword or a preferred

style of historical fencing that you focus on? What

specifically makes these so appealing for you?

3.

In defending against an opponent in any type of

sword combat, what would you say is, in general, a good method to employ? In other words,

what basic overall defensive principle of fencing would you recommend?

4.

Do you have any particular training advice from

among your own experiences to offer fellow sword enthusiasts for their individual sword

practice?

5.

What major developments do you see coming in the

near future that will affect the current revival of historical fencing? Which do you think will be among the most

important?

Mark

Rector - Chicago Swordplay Guild.

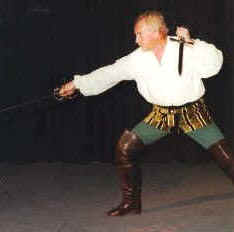

Mark is a thespian, stage-combatant, fight-director,

historical fencer, instructor, and translator of “Medieval

Combat” (Greenhill Books) a recent edition of Talhoffer’s

15th century fighting manual and editor of the

new Highland Swordsmanship from Chivalry Bookshelf.

markrector@hotmail.com Mark

Rector - Chicago Swordplay Guild.

Mark is a thespian, stage-combatant, fight-director,

historical fencer, instructor, and translator of “Medieval

Combat” (Greenhill Books) a recent edition of Talhoffer’s

15th century fighting manual and editor of the

new Highland Swordsmanship from Chivalry Bookshelf.

markrector@hotmail.com

1. To what would you attribute

your interest in historical swords? What has been the primary inspiration or source for

your own individual study of historical swordplay?

I came to fencing via the theatre. Since my early days as an actor, I have sought out

fighting roles, and have enjoyed playing some of the great fighters in Shakespeare. I have

been fortunate to work with some extremely talented and innovative fight-directors along

the way. In particular, Terry Doughman has had a huge impact on the way I think about

fencing and swordsmanship. A formidable martial artist in his own right, for years Terry

had been doing research into how the weapons he was using for the stage were actually used

in real life –not only by reading the historical texts, but by picking up the weapons

themselves and fighting with them. His theatrical fights are always based on the

fundamental reality of the weapon. He is able to infuse the insights gained from his

practical experience and historical research into his stage combat, making all his fights

unique in their brutal reality and dazzling originality. Through Terry, I had my first

glimpse of the historical manuals and the long tradition of European swordsmanship. In my

own work in the theatre and in the salle, I have continued to focus on the real nature of

the weapons I use, based on historical documentation, practical experience and a

relentless concern for the question, “what if they were sharp?”

2. Is there a favorite type of

sword or a preferred style of historical fencing that you focus on? What specifically makes these so appealing for

you?

All edged weapons from all

periods intrigue me. The Chicago Swordplay Guild concentrates on the long-sword and the

rapier. The Long-sword is a beautiful, challenging and unforgiving weapon whose use

instructs and informs every other type of personal combat. The rapier is an elegant weapon

that is just so much fun to use, and is currently one of the only historical weapons that

can be fenced safely and with intent, with minimal protection.

3. In defending against an

opponent in any type of sword combat, what would you say is, in general, a good method to

employ? In other words, what basic overall defensive principle of fencing would you

recommend?

Be where his sword is not. Maintain a good guard. Worry

more about what you’re going to do to him than what he’s going to do to you

(good tactical advice from Robert E. Lee). Above all, have patience.

4. Do you have any particular

training advice from among your own experiences to offer fellow sword enthusiasts for

their individual sword practice?

Read the historical texts. Seek out expert instruction.

Question everything. Keep it simple. Do everything in your power to protect yourself and

your fencing partners from injury.

5. What major developments do

you see coming in the near future that will affect the current revival of historical

fencing? Which do you think will be among the

most important?

Two things are happening right now that are going to have

a profound effect on historical fencing in the future. The first is that more and more

historical fencing manuscripts are being translated into English and other languages,

making them accessible to historical fencers worldwide. As more and more historical

fencers become familiar with these texts, the discourse will naturally deepen and our

understanding of the historical teachings will become more complete. The second important

development is that more and more serious teachers with an informed understanding of

fencing, swordsmanship and personal combat are emerging to guide the growing number of

martial artists who are pursuing these skills. These teachers will help shepherd an

entirely new generation of historical fencers and will insure that this martial art and

its heritage will endure.

Hank Reinhardt – Mr.

Reinhardt is a sword expert, knife expert, arms and armor expert, author, sword collector,

and founder of the original HACA. He has over 45 years of arms study behind him, was

president and founder of Museum Replicas Limited, and a consultant to CAS Iberia

sword-makers. He has written several articles on swords and combat and is the author of a

forthcoming book on swords and swordplay, was featured on the Discovery Channel’s Deadly

Duels program, and can be seen in his two new videos from Paladin Press, Viking

Swordplay and Myths of the Sword. Hank Reinhardt – Mr.

Reinhardt is a sword expert, knife expert, arms and armor expert, author, sword collector,

and founder of the original HACA. He has over 45 years of arms study behind him, was

president and founder of Museum Replicas Limited, and a consultant to CAS Iberia

sword-makers. He has written several articles on swords and combat and is the author of a

forthcoming book on swords and swordplay, was featured on the Discovery Channel’s Deadly

Duels program, and can be seen in his two new videos from Paladin Press, Viking

Swordplay and Myths of the Sword.

1. To what would you attribute

your interest in historical swords? What has been the primary inspiration or source for

your own individual study of historical swordplay?

I don’t think I can answer this question. I cannot remember a time when I wasn’t

interested in knights, arms and armor. I had learned to read before I started first grade,

and I remember reading about King Arthur, laboriously, and the Sunday comic section

featured Prince Valiant and Flash Gordon, and I devoured them every Sunday. My memory of this time is spotty, but my sisters

have told me that I was playing with a toy sword at 4-5 years old. This has stayed with me

my whole life. I have told about my brother-in-law bringing me two Japanese bayonets. He

was in the Marines in the South Pacific, and when he came home, in 1946, (I was 12) he

brought these as a present, knowing that I was into knives and swords. This led to me

fencing with a neighboring kid, and ruining the two blades. I was upset, because this

isn’t what happened in the movies, and the quest got started.

2. Is there a favorite type of

sword or a preferred style of historical fencing that you focus on? What specifically makes these so appealing for

you?

If I were forced to say which I prefer, it would be sword and shield, and my particular

preference would be a round shield, what many call a “Viking” type, and a

slightly tapering one hand sword, either Viking or Knightly cruciform. Next would be

rapier and dagger. I’ve played with just about everything, spears, axes, two hand

swords and pole arms. One style that I really liked was using small Eastern style round

shields and curved swords. This is really fun, but alas, age and smoking have torn up my

lungs, and at 67 it is just too aerobic for me now. But it is a very fast and tricky type

of sword play. I’m rather competitive, and I like the one on one competition. But I

also like using both hands. I throw my axe with either hand, and shoot a bow right or left

handed (not very well with either hand, I just love to shoot) so I much prefer using both

hands. This is why I never cared much for sport fencing, as I felt that it did not allow

you to utilize your body fully.

3. In defending against an

opponent in any type of sword combat, what would you say is, in general, a good method to

employ? In other words, what basic overall defensive principle of fencing would you

recommend?

Rather than talk about ‘defensive’ measures, consider fighting and combat in

general. Musashi’s book can be broken down into one sound statement. Your object is

to cut your enemy. In short, your objective is to win. One can be attacking even as one is

retreating or parrying or looking very confused and harmless. Indeed, if there is one

thing of paramount importance, it is deception! If you can make your opponent believe you

are attacking in one direction, and he defends in that place, he will leave another area

open. This is sound for warfare, and it is also sound for personal contest. Consider this.

Man is not a very big animal, he does not have huge powerful muscles, no massive fangs or

claws, does not spew venom, (well, some people do when one disagrees with them) or have a

built in sting. In short, he is not an impressive predator when you look at him. But he is

the greatest predator this planet has ever seen. If Tyrannosaurus were alive, his head

would grace a lot of trophy rooms! Why is Man this way? He has a brain, and he uses it

very well when it comes to killing. As long as you have a reasonable amount of physical

abilities, and you use your head, you can become very good at whatever weapon you chose.

There will be a lot of people trying, but very few that will use their brains.

4. Do you have any particular

training advice from among your own experiences to offer fellow sword enthusiasts for

their individual sword practice?

If there is any advice that anyone would care to take from an old man, it would be to not

limit yourself to one weapon, or one style, but rather to embrace all of them. Eventually

you will find that which really suits your taste and feelings, and in that you can excel.

But you will also have a good working knowledge of the many other weapons and styles out

there. You will find that you can adapt a form used for one weapon to that or another. You

will also learn to look at a weapon, and realize its potential, and how it can be used in

ways that it was not originally intended. I would give you an excellent example, but

I’m saving it for my book.

5. What major developments do

you see coming in the near future that will affect the current revival of historical

fencing? Which do you think will be among the

most important?

I think the most important developments will

be in sparring equipment that will allow people to spar much more realistically, and yet

much safer. I do not think there will ever be a development that will allow accurate,

full-speed sparring that would won’t be dangerous, but I do think that there are

improvements on the way, and I know of one or two. I think the interest will continue to

grow, and would not be surprised to see several organizations sponsoring tournaments on a

nationwide basis. I think the types of tournaments, or sparring will probably be rapier

and dagger, and sword and shield, and probably small sword. Rules for these can be easily

developed. Jousting on horseback is quite likely to develop from an act to a full-fledged

contest. But fighting on foot with a weapon in full plate will always be judged as a

sport, simply because there is no practical way to judge it as a martial art.

Marco Rubboli – Associazione Sala

d’Arme Achille Marozzo, Italy. Marco is a historical-fencing

researcher-practitioner and translator of a new modern Italian version of Fillipo

Vadi’s 15th century text soon to be published in English. Marco Rubboli – Associazione Sala

d’Arme Achille Marozzo, Italy. Marco is a historical-fencing

researcher-practitioner and translator of a new modern Italian version of Fillipo

Vadi’s 15th century text soon to be published in English.

1. To what would you attribute

your interest in historical swords? What has been the primary inspiration or source for

your own individual study of historical swordplay?

It is not easy to trace back the origin of my interest in swordfighting and knightly

feats. The first readings of my childhood

were Salgari's novels, full of duels and fighting, and easy translations of Homer's epic

poems. Later on I read Malory, Chretien de Troyes, etc., as well as many fantasy

novels. In the meanwhile I practised archery and bow-hunting, trekking, skiing and many

different sports, as I was unaware that there was a possibility of reconstructing old

western fencing. Then I began making shows about medieval sword fighting (stage combat),

and practising fencing: foil for a few months, then sabre. But I think that the art to

which I really wanted to dedicate myself, during all my life, was historical fencing. The first source I had in my hands was the

treatise of Fiore dei Liberi, then after a few months I found Filippo Vadi, Achille

Marozzo and Antonio Manciolino. There is a clear relationship among all those works,

showing an evolution going from Fiore dei Liberi to Vadi, to the Bolognese School

represented by Marozzo and Manciolino, even if we could identify some important

differences between the medieval authors and the Renaissance Bolognese school. At first I

was very attracted by the martial instructions of the medieval authors (which I still find

very interesting) only then I began to appreciate the more refined fighting style of the

Italian schools of the beginning of the XVI century.

2. Is there a favorite type of

sword or a preferred style of historical fencing that you focus on? What specifically makes these so appealing for

you?

Very soon I decided to concentrate my efforts on the “spada da lato”, i.e. the

cut and thrust sword of the beginning of the XVI century, used by authors like Marozzo,

Manciolino, and later in the same century by Dalle Agocchie or Viggiani. It is a kind of sword suitable for a military and

a civil use, for duels as well as for street fighting, and it can be used with a big

variety of shields, the dagger, the cloak, but also alone.

It has a light and quick blade, but with still much cutting power, and

indeed its use, as it appears from manuals, is 50% thrusting and 50% cutting. But there is also another reason, apart from the

very good characteristics of the weapon itself: if in the works of the medieval authors

there can be many doubts on interpretation, the Bolognese school treatises are a good deal

more clear, if one can compare some of them keeping in mind the eternal fencing principles

like parry ans risposte, etc. Moreover, as

for the play of the single sword (the first one that I examined) I could count on some

years of sport sabre lessons, that proved to be very useful. The doubts that one can still have reading the

first authors like Marozzo and Manciolino generally can be easily cleared if one refers to

Dalle Agocchie (sistematic analysis of all the offensive and defensive actions) and

Viggiani (on general principles of fencing).

3. In defending against an

opponent in any type of sword combat, what would you say is, in general, a good method to

employ? In other words, what basic overall defensive principle of fencing would you

recommend?

It is not easy to give such a general advice, valid for any kind of sword combat. But I

think I'd refer to the principles of my favourite cut and thrust play of the Bolognese

school, because I'm convinced that they may be generalized and adapted to include more or

less any kind of sword. The guards (always changing) should be more “open”

(invitation) if the weapon is heavy, more straight on the line of attack if the sword is a

light one, but they always should give the fencer an idea of which is the angle from where

the opponent can attack and which is the angle that he can't use because it is already

defended by your sword, i.e. the guards always have to make an invitation to the opponent,

discovering some target and covering some other one. One can see it in medieval treatises,

in Renaissance texts, and even in the guards used in modern fencing. As for the kind of actions to be used, generally

speaking an action that can be executed well with almost any kind of sword is a “

mezzo tempo” cut (or thrust if we're speaking of a sword that can only thrust, but

with a cut the action is more easily executed) to the raised hand or arm of the opponent,

followed by an evading motion. A “mezzo

tempo” blow followed by a parry, on the other hand, requires a light weapon and an

expert fencer. Another old but always valid

option is a classic parry and risposte, paying attention that if the weapon of the

opponent is heavy and his blow is strong and clear you should counter-cut more to sustain

the impact, while if the weapon is light and quick and the blow could still be a feint you

should make a more stable parry. In any case

you should not let your weapon go far from your body while parrying, like Master Filippo

Vadi recommends giving instructions for the use of the medieval 2-hands sword (!). If one has a secondary weapon another very good

kind of action is a “tempo insieme” counterattack, i.e. while you parry with

your secondary weapon you attack with your sword, at the very same time. Usually this action is executed with a side-step,

that on one hand is an evading motion that helps the parry, on the other hand it helps the

attack executed with the sword because it permits to the fencer to attack from the side of

the opponent, from an unusual angle.

4. Do you have any particular

training advice from among your own experiences to offer fellow sword enthusiasts for

their individual sword practice?

One thing that beginners certainly has to avoid is to train alone, without a qualified

instructor: bad habits are very difficult to dismiss.

Also, practising alone, without a sparring partner, is usually of limited

value, although it can help to memorize techniques and increase precision. On the

contrary, it is very important to practise techniques with the instructor, that can signal

and emend mistakes. It is also important to

try the techniques during full speed combat, both with beginners or with people unaware of

the techniques used, and with experts that those techniques them well and know how to

react. Free combat (that should be practised

very often) should always be seen as a change to train in techniques and good fencing

principles, not much as hard competition. Then

there are some individual exercises intended to develop individual skills, for example to

practise parrying the “wall” exercise is very good (you stand with a wall behind

you, without the possibility to go back, and you can only parry the multiple attacks

delivered by your sparring partner, without trying to hit him). For developing a good parry and risposte a good

exercise is to wait for the opponent attack, and practise parry and risposte without any

step, or even seated. Anyhow, the Bolognese

school's techniques, besides being valid techniques in a fight, are all very good

exercises to develop any skill required to a fencer.

5. What major developments do

you see coming in the near future that will affect the current revival of historical

fencing? Which do you think will be among the

most important?

A very important thing is the increasing connection among interested groups and

individuals, that leads to the sharing of information and texts, and to make comparison

between ideas, methods etc. A good deal of

that is due to the Internet, without any doubt. Another

important effect of the Internet is the possibility to “publish” articles and

original texts, making them available to all practitioners. Now if an average University student (for

example) looks for historical fencing he can find a lot of groups and material on the

Internet, while only ten years ago he couldn't find anything, searching in his hometown. All those changes are making clear that the

Western world has a huge and valid martial heritage (with important links to our cultural

identity and our old and high ethic values). There

is still a big deal of work to be done, to bring this heritage back to the people of the

Western world, but I think that there are many valid people working at it. I think that we could be near to the point where

the general public comes to know that we exist, and this is already a big victory. What will come next, it is difficult to say.

John Waller – As leader

in the field, Mr. Waller is Director of Living-Interpretation at the Royal Armouries, in

Leeds, UK. He is a historical weapons expert, martial artist, jouster, fight-arranger, 30+

year veteran of historical fencing and stage combat, is founder of the new European Historical Combat Guild, and co-author of

a new book on historical combat for performance fighting. He was featured in the video

program Masters of Defence and in the History Channel’s Arms in Action

series. He was a theatrical fight instructor at leading London drama schools and is known

for the fights he arranged for the cult-film Hawk the Slayer. John Waller – As leader

in the field, Mr. Waller is Director of Living-Interpretation at the Royal Armouries, in

Leeds, UK. He is a historical weapons expert, martial artist, jouster, fight-arranger, 30+

year veteran of historical fencing and stage combat, is founder of the new European Historical Combat Guild, and co-author of

a new book on historical combat for performance fighting. He was featured in the video

program Masters of Defence and in the History Channel’s Arms in Action

series. He was a theatrical fight instructor at leading London drama schools and is known

for the fights he arranged for the cult-film Hawk the Slayer.

1. To what would you attribute your interest in historical swords? What has been the

primary inspiration or source for your own individual study of historical swordplay?

I have been interested in history for so long now that it must be a mixture of so many

things. Films, arms and armour, books of course and the images contained in them, also a

love of all things connected with “medieval life.” I have been an archer since

boyhood, I am also a falconer and a horseman.

2. Is there a favorite type of

sword or a preferred style of historical fencing that you focus on? What specifically makes these so appealing for

you?

I do not have a favorite type of sword or a preferred style of historical swordfighting,

my interest ranges from the ancient world through to the modern combat techniques used by

the special forces of today. What makes the whole process so interesting is that I believe

that nothing is new and in reality the same principles have been used by the best masters

in all cultures and at all times.

3. In defending against an

opponent in any type of sword combat, what would you say is, in general, a good method to

employ? In other words, what basic overall defensive principle of fencing would you

recommend?

The best method of defence is not to be there. Always keep your weapons between you and

your opponent, he has to go past them to get at you. Next let your opponent attack and

when you see an opening get it over as quick as possible, or attack if you can continually

from the outset and do not give him a chance to attack you. The longer any encounter goes

on the more chance there is that you will suffer some injury, even if you win.

4. Do you have any particular

training advice from among your own experiences to offer fellow sword enthusiasts for

their individual sword practice?

I think the best way to answer this is to quote from the European Historical Combat

Guild’s principles: Eye Contact, Balance, Intention, Control, Economy of Effort. These are what anyone should master in any sword

combat whether in reality or in practice

5. What major developments do

you see coming in the near future that will affect the current revival of historical

fencing? Which do you think will be among the

most important?

I believe that collaboration between such organisations as the HACA and our own new EHCG

(European Historical Combat Guild) will bring together those who wish to learn about

European historical combat in such a way that creates a beneficial atmosphere. There are many individuals and groups that have

lots to say, the more they get the chance, the more we should learn. There is now a close relationship between the

Royal Armouries and the Higgins, as there is between HACA and EHCG so we are on our way. |