|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

A

Short Introduction to

|

|

|

|

|

Renaissance

Adaptations

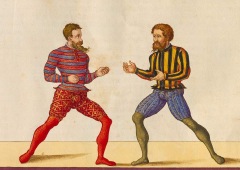

Renaissance

Masters systematized and innovated the study of Western fighting skills

into sophisticated, versatile, and highly effective martial arts eventually

culminating in the development of the penultimate weapon of street-fighting

and dueling, the quick and vicious rapier. Through

experiment and observation they discerned that the thrust traveled

in a shorter line than the arc of a cut and against an unarmored foe

would strike sooner and reach farther. The

rapier was developed along these principles. Thrusting was already

well known in Medieval combat and the new style of foyning fence was

thus not any “evolution”, but rather an adaptation to

a changed environment. Rather

than for war or battlefield, the slender, deceptive rapier was a personal

weapon for civilian-wear and private quarrels.

It was first designed for the needs of back-alley encounters

and public ambush. Indeed,

it was the first truly civilian weapon for urban self-defence developed

in any society. It rose from practical tool, to popular “gentleman's

art”. Elegant in its lethality, it represents one of

the most innovative and original aspects of Western martial culture

and one with no parallel in other cultures. While never eclipsing

cutting swords entirely, as a specialized weapon for personal single-combat,

it was unequaled for almost 200 years until the widespread adoption

of effective and reliable handguns.

Renaissance

Masters systematized and innovated the study of Western fighting skills

into sophisticated, versatile, and highly effective martial arts eventually

culminating in the development of the penultimate weapon of street-fighting

and dueling, the quick and vicious rapier. Through

experiment and observation they discerned that the thrust traveled

in a shorter line than the arc of a cut and against an unarmored foe

would strike sooner and reach farther. The

rapier was developed along these principles. Thrusting was already

well known in Medieval combat and the new style of foyning fence was

thus not any “evolution”, but rather an adaptation to

a changed environment. Rather

than for war or battlefield, the slender, deceptive rapier was a personal

weapon for civilian-wear and private quarrels.

It was first designed for the needs of back-alley encounters

and public ambush. Indeed,

it was the first truly civilian weapon for urban self-defence developed

in any society. It rose from practical tool, to popular “gentleman's

art”. Elegant in its lethality, it represents one of

the most innovative and original aspects of Western martial culture

and one with no parallel in other cultures. While never eclipsing

cutting swords entirely, as a specialized weapon for personal single-combat,

it was unequaled for almost 200 years until the widespread adoption

of effective and reliable handguns.

|

|

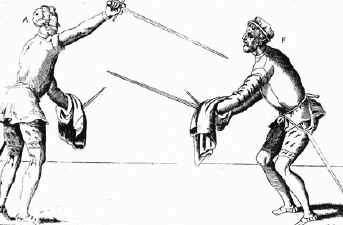

Like

much of progress in Renaissance learning and science, advances in

self-defense were based on what had already been commonly established

for centuries. They were not able to achieve

their progress in a vacuum. There is an obvious direct and discernible

link between the brutal, practical fighting methods of the Middle

Ages and the more sophisticated, elegant Renaissance fencing systems.

No tradition of fighting or methodology of combat exists

by itself. It comes into being due to

environmental pressure as only a processing or refinement of what

existed previously. So it was with the

fencing arts of the Renaissance. They

followed a more than 2,000-year-old military tradition within Western

civilization of close-combat proficiency.

Like

much of progress in Renaissance learning and science, advances in

self-defense were based on what had already been commonly established

for centuries. They were not able to achieve

their progress in a vacuum. There is an obvious direct and discernible

link between the brutal, practical fighting methods of the Middle

Ages and the more sophisticated, elegant Renaissance fencing systems.

No tradition of fighting or methodology of combat exists

by itself. It comes into being due to

environmental pressure as only a processing or refinement of what

existed previously. So it was with the

fencing arts of the Renaissance. They

followed a more than 2,000-year-old military tradition within Western

civilization of close-combat proficiency.

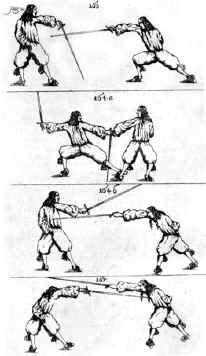

The

techniques developed and taught by the Masters of Defence were not

“tricks” nor merely based only on brute strength.

They were moves they knew worked in combat, that they had discerned,

had named, and had taught to others. But,

to fencers in much later centuries, (bounded by rules of deportment

and the etiquette of convention) these earlier fighting styles (designed

to face a range of arms and armors) would naturally seem less “scientific”.

With the disconnection that occurred between older traditions and

the precise sporting swordplay of later gentlemen duelists, it is

reasonable that the earlier, more dynamic, flexible, and inclusive

methods would incorrectly seem to only be a mix of chaotic gimmicks

unconnected by any larger “theory”.

The

techniques developed and taught by the Masters of Defence were not

“tricks” nor merely based only on brute strength.

They were moves they knew worked in combat, that they had discerned,

had named, and had taught to others. But,

to fencers in much later centuries, (bounded by rules of deportment

and the etiquette of convention) these earlier fighting styles (designed

to face a range of arms and armors) would naturally seem less “scientific”.

With the disconnection that occurred between older traditions and

the precise sporting swordplay of later gentlemen duelists, it is

reasonable that the earlier, more dynamic, flexible, and inclusive

methods would incorrectly seem to only be a mix of chaotic gimmicks

unconnected by any larger “theory”.

Eventually, due to changing historical and social forces, the traditional martial skills and teachings of European Masters of Defence fell out of common use. Little to nothing of their methods actually survive in modern fencing sports today which, based on conceptions of 18th century small-sword combat, are far removed from their martial origins in the Renaissance. Later centuries in Europe saw only limited and narrow application of swords and traditional arms, only some of which survived for a time to become martial sports.

|

|

|

Modern

Research & Practice

In

a sense, our European martial culture is itself something still very

much with us today. But it now bares little resemblance to its Renaissance

heritage. The technological revolution

in Western military science which swept the 18th century left behind

the old ideas of an individual, armored warrior trained in personal

hand-to-hand combat. It was replaced with the new “Western Way

of war” utilizing ballistics and associated organizational concepts.

This very approach itself, emphasizing more and more a technical,

mechanical, and industrial method of armed combat, is

the Western martial “tradition” now. Indeed, it is this

very martial way that is now the model for all modern armed forces

the world over. In a sense, to see a modern

aircraft carrier, fighter squadron, or armored battalion is very much

the embodiment of a continuing and ever evolving European martial

tradition.

In

a sense, our European martial culture is itself something still very

much with us today. But it now bares little resemblance to its Renaissance

heritage. The technological revolution

in Western military science which swept the 18th century left behind

the old ideas of an individual, armored warrior trained in personal

hand-to-hand combat. It was replaced with the new “Western Way

of war” utilizing ballistics and associated organizational concepts.

This very approach itself, emphasizing more and more a technical,

mechanical, and industrial method of armed combat, is

the Western martial “tradition” now. Indeed, it is this

very martial way that is now the model for all modern armed forces

the world over. In a sense, to see a modern

aircraft carrier, fighter squadron, or armored battalion is very much

the embodiment of a continuing and ever evolving European martial

tradition.

From

the time of the ancient Greeks onward Western Civilization has always

been a source of uniquely resourceful ideas and specialized innovation.

For better or worse, the same technical ingenuity that was

applied to classical arts and sciences was directed equally towards

the weapons of war and skills of battle. In

short, the Western world's contributions to martial arts are far-ranging

and far-reaching. Modern boxing, wrestling,

and sport fencing are the very blunt and shallow tip of a deep history

which, when explored and developed properly, provides a link to traditions

which are as rich and complex as any to emerge from Asia.

Today, as more and more students of the martial

arts of Renaissance Europe ("MARE") earnestly study the subject they

are recovering this heritage and reclaiming it from myth, misconception,

and fantasy. This is not about

costumed role-play or theatrical stunt shows, but scholarly research

combined with genuine martial arts training.

As a result a more realistic

appreciation of our Western martial culture is now emerging full force.

From

the time of the ancient Greeks onward Western Civilization has always

been a source of uniquely resourceful ideas and specialized innovation.

For better or worse, the same technical ingenuity that was

applied to classical arts and sciences was directed equally towards

the weapons of war and skills of battle. In

short, the Western world's contributions to martial arts are far-ranging

and far-reaching. Modern boxing, wrestling,

and sport fencing are the very blunt and shallow tip of a deep history

which, when explored and developed properly, provides a link to traditions

which are as rich and complex as any to emerge from Asia.

Today, as more and more students of the martial

arts of Renaissance Europe ("MARE") earnestly study the subject they

are recovering this heritage and reclaiming it from myth, misconception,

and fantasy. This is not about

costumed role-play or theatrical stunt shows, but scholarly research

combined with genuine martial arts training.

As a result a more realistic

appreciation of our Western martial culture is now emerging full force.

See

also

Introduction to Renaissance Martial Arts Literature

and

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||