Liber

de Arte Gladitoria Dimicandi

Text and Images from Fillipo Vadi's

"Book on the Art of Fighting with Swords" - c. 1482 - 1487

In

its continuing effort to bring to light the history and truth of Medieval

fighting arts and promote accurate research into European martial

culture, ARMA is proud to present this material from the rare 15th

century Italian fencing manual of Filipo Vadi. Vadi, along with Fiore

Dei Liberi, is one of two major Medieval Italian Masters of Arms.

While produced two generations after Dei Liberi's work, Vadi's work

shows unmistakeable connection to earlier methods, yet reveals changes

that reflect his own style as well as improved armor. Vadi listed

the same number of blows as Dei Liberi (six cuts and one thrust) and

gave a similar, if not identical, series of twelve guards with only

a few name additions. Although it is rapidly changing, little work

so far has been done on Vadi's material, but it is an important addition

to the curriculum of today's student of historical European martial

arts. The material presents substantial insight into fighting with

the long-sword, poleaxe, spear, and dagger. Many students also feel

study of Vadi offers insights into Fiore's method. Vadi refers to

the craft as an art or science and relates it to geometry. Written

in rhyme, it reads rather cryptic today to those less familiar with

the craft, but his advice is sound and several gems are buried within

it. In

its continuing effort to bring to light the history and truth of Medieval

fighting arts and promote accurate research into European martial

culture, ARMA is proud to present this material from the rare 15th

century Italian fencing manual of Filipo Vadi. Vadi, along with Fiore

Dei Liberi, is one of two major Medieval Italian Masters of Arms.

While produced two generations after Dei Liberi's work, Vadi's work

shows unmistakeable connection to earlier methods, yet reveals changes

that reflect his own style as well as improved armor. Vadi listed

the same number of blows as Dei Liberi (six cuts and one thrust) and

gave a similar, if not identical, series of twelve guards with only

a few name additions. Although it is rapidly changing, little work

so far has been done on Vadi's material, but it is an important addition

to the curriculum of today's student of historical European martial

arts. The material presents substantial insight into fighting with

the long-sword, poleaxe, spear, and dagger. Many students also feel

study of Vadi offers insights into Fiore's method. Vadi refers to

the craft as an art or science and relates it to geometry. Written

in rhyme, it reads rather cryptic today to those less familiar with

the craft, but his advice is sound and several gems are buried within

it.

Two new English of Vadi's work will be available from Luca Porzio

(Chivalry Bookshelf) and Marco Rubboli (Paladin Press). A Modern Italian

edition by Marco Rubboli & Luca Ceasri is now available from Gli

Archi press, as is one from Nova Scrimia. Below we present a rough

draft translation of Vadi's introduction and 16 chapters by Luca Porzio,

along with sharp images of the complete illustrations courtesy of

Marco Rubboli's recent Italian translation edition by permission.

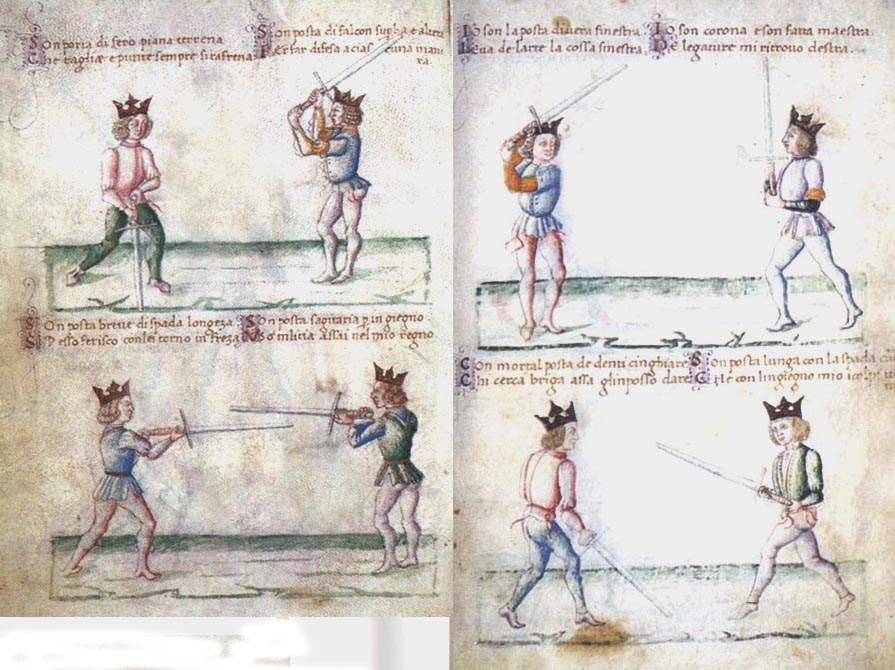

The original manuscript is in color as can be seen to the side here.

|

| |

Recto 15 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Verso 15 |

Recto 16 |

Verso 16 |

Recto 17 |

|

|

|

|

| 17 & 18 |

Verso 18 |

Recto 19 |

Verso 19 |

|

|

|

|

| Recto 20 |

Verso 20 |

21 & 22 |

22 & 23 |

|

|

|

|

| 23 & 24 |

Verso 25 |

Recto 25 |

26 & 26 |

|

|

|

|

| Recto 27 |

Verso 27 |

28 & 28 |

29 & 29 |

|

|

|

|

| 30 & 30 |

Recto 31 |

Verso 31 |

32 & 32 |

|

|

|

|

| 33 & 33 |

34 & 34 |

35 & 35 |

36 & 36 |

|

|

|

|

| Recto 37 |

Verso 37 |

38 & 38 |

39 & 39 |

|

|

|

|

| 40 & 40 |

Recto 41 |

Verso 41 |

42 & 42 |

Liber de Arte Gladiatoria

Dimicandi

("Book on the Art of Fighting With Swords")

Filipo Vadi c. 1482-1487

Draft translation by Luca Porzio from the Bascetti Edition.

Editing and commentary by John Clements.

Notes on the Work:

What we know of the late 15th century Italian Master of Arms and

teacher of swordplay, Philippo Vadi, is little more than a name. Vadi

was one of a number of fencing teachers of his days travelling from

court to court instructing in the noble sicence and Art of defence.

Vadi tells us he was born in Pisa, lived in the second half of the

fifteenth century, and had learned his fencing skills “from the

practical experience and doctrine of many masters of arms of different

countries, well versed in their Art”. The work begins with some

Latin verses dedicating it to Guido da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino,

followed by Vadi’s introduction. Although Vadi dedicated his

verses to Guidobaldo, it is unknown if he ever was ever supported

by the Duke or ws ever a member of the court of Urbino, where in the

days of Federico (another Duke of Urbino) fencing teachers

were regularly employed.

His verses describe a range of techniques and principles for various

knightly weapons. Besides Fiore Dei Liberi manual of 1410, Vadi represents

the only other Italian master of Medieval weapons and fencing that

we now have. Like his Spanish contemporary, Pietro Monte (who studied

and taught in Italy), Vadi also presents material generations later

than Fiore Dei Liberi, Sigmund Ringeck, or Hans Talhoffer. Despite

this, his work is strongly reminiscent of Dei Liberi’s and may

be influence directly by him. Its resemblance is strong yet Master

Vadi clearly wrote of his own understanding and method. The manual

covers the standard knightly weapons of the time: spada (sword –in

this case long sword), daga (dagger), lanza (spear), and azza (polaxe).

His work also includes material on unarmed combat or wrestling and

defense against a dagger while unarmed. The text is also well illustrated

with dozens of deceptions of stances, techniques, and movements. Thus

while providing an additional study source and a comparison to other

Medieval styles, Vadi is a valuable primary reference for today’s

student of Medieval swordsmanship.

Illustrated with panels of simple figures in side profiles, the work

is presented as a kind of study guide. Each illustration depicts a

posture or attack or counter-attack along with a short caption describing

the concept or action.

In translating and transcribing Medieval verses in to modern English

certain captions had to be separated or combined in order to render

them more easily understandable. To retain the rhythm of master Vadi’s

original wording this was done only when necessary and in a manner

that preserved the idea behind the verse.

By time he produced his text, Vadi would have been in his maturity

and perhaps beyond his physical prime but could call on many years

of experience acquired during the 1460s and 1470s.

The Book on the Art of Fighting With Swords is dedicated to

Guido, Duke of Urbino(where, in earlier days fencing teachers were

regularly employed). The dates 1482-1487 are the range in which scholars

place the writing, while 1482 is the year in which Guido, Duke of

Urbino, succeeded to his father, and 1487 is the year of the first

inventory in which Vadi’s book was recorded. In his introduction,

Vadi describes his lifetime pursuit of fencing, and how he put his

learning in his book, and how the Art of fencing is valorous craft

which should not be revealed to “uncouth men”, and he relates

fencing with a noble spirit. He then says that all which he wrote

in the book has been personally tested by himself, and that other

dubious things were not included. After this he speaks of the superiority

of intelligence over strength, which he declares makes possible for

a man to defeat more than one foe, or for the weak to defeat the strong.

Finally, he says that anyone well versed in fencing is free to modify

his work. It is interesting to note he states he studied from the

experience and practical doctrines of masters of multiple countries.

Vadi also clearly mentions that his method is designed for battlefield,

fights, and “other warlike events”, indicating no real distinction

for fighting in war or personal combat. This is the same view held

by his contemporary Pietro Monte.

It is worth pointing out that Vadi is one of few to describe that

a pommel should be “round in order to fit in the fist” and

that the handle should be square-shaped. He also suggests the size

of a hilt should be square-shaped and the length of the handle plus

the pommel, plus that unusually it should even be “pointed to

wound and cut”. For a sword against heavy armor (“in arme”)

Vadi is saying it should only be sharp about 3.5 inches (“four

fingers from the tip”). This is highly significant for declaring

that some swords specifically intended for use against plate armor

and the requisite half-sword techniques (“mezza spada” or

“Halb-Schwert” in German”) that would be used were

indeed only partially sharpened. This implies that such techniques

were in fact employed with blades that were not fully sharp their

entire length.

The text was originally written in verse form and so is sometimes

obscure in portions sounds overly complex as a result. Some chapters

are only very short sections. Vadi also occasionally uses metaphor

whose meaning may no longer be clear. The translation here however

is presented without interpretation. Because Vadi wrote in verse the

text often lacks details where it needs them while at other times

contains statements meant only for rhyme. Translating this into Modern

English therefore poses some problems. It is suggested to not to try

to read too much into passages where it appears obscure or even obtuse.

In the future more precise wording will become available. A few end

notes are provided for some of the more difficult passages.

Vadi refers to several types of the spada (“sword”)

including large swords, small swords, and spada da doi mane

(“two handed swords”), all of which appear as forms of long-sword

or great-sword.

Introduction by Philippo Vadi of Pisa

In the first and thriving years of my life I was spurred by natural

attitude, produced by my sincere heart without cowardice, towards

warlike acts and things so that, while growing as time wanted in strength

and knowledge, I strove to learn more about the Art and cleverness

of the said warlike acts and things: as is the use of sword, spear,

dagger and polaxe.

Of these things, thanks to the help of God, I acquired good knowledge,

from the practical experience and doctrine of many masters of arms

of different countries, well versed in their Art. And not to lessen,

but instead to augment this doctrine so that it will not perish for

my negligence, for it is a source of no small help in battle, war,

fights and other warlike events (but instead it gives to men versed

in this knowledge a very useful aid ), I decided to write a book on

things that later will be better described: including pictures and

various examples, usable by anybody knowing this subject for attack,

defence, and many clever considerations.

This way he, with a generous heart, who sees my work should love

it as a jewel and treasure and keep it in his heart, so that never,

by means, should this Art and doctrine fall into the hands of unrefined

and low born men. Because Heaven did not generate these men, unrefined

and without wit or skill, and without any agility, but they were rather

generated as unreasonable animals, only able to bear burdens and to

do vile and unrefined works. For this reason I rightly tell you that

they are in every way alien to this science, while the opposite is

true, in my opinion, for anybody of perspicacious talent and lovely

limbs, as are courtesans, scholars, barons, princes, dukes and kings,

who should be called to learn this science, following the principle

of Instituta, which says: the imperial majesty has not only

to be honored with arms, but also with sacred laws.

And do not think that in this book can be anything false or enveloped

in error, because cutting and taking away dubious things, I only have

written those things I saw and experienced personally, beginning to

express our intention with the aid and grace of the almighty God whose

name be blessed forever.

And because some irrational animals do naturally their actions, without

any human science, by nature they lack science as man lacks weapons,

so that nature gives man hands, intelligence and thought to make up

for the lack of natural weapons, so that he doesn’t need other

things; and so man has no weapon or Artifice, to better learn to use

all weapons and Artifices. So man needs, among all animals, intelligence

and reason, in which flourish Art and science, and in these and other

things he surpasses all animals.

But every learned and clever man surpasses other men bigger and stronger,

as was correctly said: intelligence surpasses strength, and what is

more and nearly incredible, the sage dominates the stars. From the

said talent and other subtle thoughts is born an Art of winning and

conquering anyone wanting to fight and contrast; and it not only happens

that one man conquers the other, but it is also possible that one

man conquers many others, and it is thus shown not only the way to

assault the enemy and to repair and defend from him, but also it is

taught how to disarm him.

And with these documents often it happens that a man weak and of

small stature submits, brings to the ground and conquers one large,

strong and valiant, and the same way the humble conquers the haughty

and the unarmed conquers the armed; and many times he who is on foot

conquers a horseman. Since it would be very unbecoming that such a

noble doctrine should perish and fail by carelessness, I Philippo

of Vadi from Pisa, having practiced this Art from the years of my

youth, having searched and traveled many different countries and lands,

castles and cities to learn from many masters perfect in the Art,

and having, by the Grace of God, acquired a good part of learning,

decided to compose this booklet, in which it will be exposed and shown

at least the fighting with four weapons, that are spear, sword, dagger

and polaxe.

And in this book will be described rules, ways and acts of this Art,

showing examples with various pictures, so that everybody not experienced

in the Art may be able to understand and know the way of attacking,

and by which tricks and cunnings he might defend himself from the

enemy’s tricks and strikes; and putting in this book only that

doctrine, good and true, which I learned trough hard work, big worries

and nights without sleep, from the better masters, and also putting

in it things I devised and tried in action. Remembering to anybody

not to undertake with temerity the study of this Art and science,

if he is not magnanimous and full of valor; for any man slow-witted,

fearful and vile shall be driven out and not admitted to such a high

noble and courteous enterprise. For to this doctrine should be invited

only soldiers, man at arms, scholars, barons, lords, dukes, princes

and kings of lands, some of which are up to rule the republic, and

some others to defend orphans and widows: and both are divine and

pious deeds.

And should this booklet of mine fall into the hands of someone learned

in the Art, and should it seem to him that there is any superfluous

or lacking thing, he might cut, lessen or augment what he deems necessary,

as from now I put myself under his correction and censure.

Begin the First Chapter.

If someone would like to know and understand

If fencing is an Art or else a science

I say that you should note my opinion

Consider well my sentence

It is a true science not an Art

As I will show you briefly

Geometry divides and separates

With infinite numbers and measures

And fills with science his papers

The sword to her care is subject

It is good to measure blows and steps

To find your trust in science

Fencing is born from geometry

To her it is subject

And both of them are endless

And if you learn my doctrines

You will be able to answer with reason

And take away the rose from the thorns

To make your opinion clearer

And to sharpen your intellect

So you may able to answer to anyone:

As music adorns and combines

The Art of sound and lyrics

And with science makes it perfect

So geometry and music combine

Their scientific virtues in the sword

To adorn the bright star of mars

Now if you like what I say

And the reasons I write

Keep them in your mind and do not lose them

So tell the truth as I say

That in fencing there is no end

As every reverse finds his right

Contrary by contrary without an end

Chapter 2

Measures of the Spada da doi Mane (Two Handed Sword).

The sword should be of the correct measure

With the pommel just under the arm (pit),

As here is written

To avoid any hindrance:

The pommel should be round to fit the closed hand

Do this and you will not be in troubles

And know for sure

That the handle should be a span long

Who has not this measures will be confused

To prevent your mind from being deceived

The hilt should be as long as handle and

pommel ensemble, and you will not be endangered

The hilt is squared and strong as needed

With iron broad and pointed

His duty being to wound and cut

Be sure to note the following:

If using the sword in arme’ (“in plate armor”)

It must be sharp four fingers from the tip

The grip as said above

The pointed hilt, and note this writing

Chapter 3

Doctrine of the Sword

Brandish manfully the sword, for it is a cross and a royal weapon,

and with it match a gallant heart.

If you are clever, you must consider how to climb these stairs.

The Art of the sword consists only in crossing,

putting both strikes and thrusts in their right place,

to make war against he who wants to fight you.

From one side there are defending right strikes (colpi diritti)

going to one side (the right) , reverses (riversi) make offence

from the other side (the left).

The true edge should strike with the right blow,

and be aware of what I say,

riverso and falso (false edge) go together.

And you should do as the saying tells you: set

yourself in posta (guard) brandishing the sword, and

advancing or going back, always retain a side stance.

To make not your play in vain enter from the side

your face looks toward, and this should not seem weird to you

Set your sword pointing towards your enemy’s face, and quickly

strike.

You must be very shrewd, the eye towards the weapons

which can strike you, seizing measure and timing,

and with a proper posture.

Match your spirit while defending, and arms and feet

with good measure, if you want to gain any honor.

Be well aware and understand what I write, if your

compagno (“comrade” or “partner”) strikes

with his sword, with

yours try to cross blades.

Be sure you never go out of the way, go with

coverta (covering) and with the point towards the

face, your strikes to the head shall go.

Cross play and you will not be conquered.

If your foe crosses wide, push, for you do not want

to be divided from him.

When his (sword) comes to mezzo spada (half sword)

close towards him, as reason demands, leave

gioco largo (long play) and assail him.

Often it happens that a man feels to not have enough

fortitude, in this case facts are needed, and not words.

Go swiftly out of the way, make coverta with the

good manreverso, and follow quickly with mandritto.

If you have not lost your wit, leave gioco largo and

stay within gioco stretto (close play), you will make

fortitude change its side.

And note this saying: when you cross blades, cross

them resolutely, to lessen the sword’s shortcoming.

Know that cleverness wins against strength,

do your coverta and quickly strike, at close and wide you

will take down strength.

And if you want to make him feel your point, go out

of the way with a sidestep, make him feel your point

in his chest.

With point high and pommel low, the arms extended,

with good coverta pass on your left side with a good step,

and if the point finds its way open, even from the

outer side, do not fear: you will give him your offering.

Then close and grab his handle, and if this you

cannot do, then beat his sword and do your duty.

Be always matched with your enemy while moving,

attacking or defending, and what I say never forget:

as soon as you see his sword begin to move, or if he

moves, or even if he attacks, go back or let him find you near.

He who wants to have honor in arms should have

knowledge, fortitude and courage; if these he lacks,

he’d better renounce.

And you need a valiant heart, and if a larger man

seems strong to you, be clever and you will gain the

advantage.

Be sure, as death is, that your play comes not from

courtesy, against he who wants to shame you.

And note this sentence: you know your heart, not

your enemy’s, never use such fantasy.

Be very clever, if you want to last long in this Art,

you will have good fruits from that.

Note also that: he who wants to fight too much, in

one thousand at least once will soil his luck,

so losing honor from one error only; he thinks high

things which are low, and often clashes;

often he causes grumblings, often he quarrels:

in these things it is seen who in the Art is learned.

If tongue could cut for any reason, and as the sword

could do, the dead would be infinite.

Be sure that your mind will not fall, that with reason

it undertakes your defence, and that with justice goes justly.

He who wants to attack others without reason will

surely damn his body and soul, and shame his teacher.

Also you must always remember to pay respect to

your teacher, for money does not pay what he gives you.

He who wants to be able and learned in

swordsmanship should learn to do and teach, and not

make mistakes.

Loving loyalty you will be able to speak to King and

Princes, so that they will be able to use the Art.

For their duty is to govern, to maintain justice, and

to care for widows, orphans and other problems.

So from this Art comes all sorts of good, with arms

cities are subdued and all the crowds restrained;

and in itself has such dignity, that often it brings joy

to the heart, and always drives out cowardice. You

should acquire treasure and honor and, above any

other care, always maintain yourself in your lord’s grace.

If you will be renowned in the Art, you will never be

poor, in any place. This virtue is so glorious that,

if even once poverty would show you his cards, then

wealth will embrace you thanks to your Art.

Sometimes you will be as an extinguished light: do

not doubt, you will soon be back.

To gain the Art, not the old but the new, no effort

was too great and very happy I am of having found it.

I keep it secret, but as I let it go, I swear, it gives me

riches and so it happens to those having this virtue.

*Note: “Coverta” or covering, means literally blanket

and refers to controlling the enemy’s sword with your own or

sometimes with your hand. It consists of maintaining blade contact

while entering.

Chapter 4

This Art is so gentle and noble,

she teaches man how to go,

and makes the eye quick, valiant and gentleman-like.

This Art teaches you how to turn,

and how to defend and remain steady,

and how to parry cuts and thrusts.

How many persons died,

because they did not like the Art,

and so they closed their doors of life.

No treasure is greater than life,

and to defend it everyone does its best,

he strives to keep it as well as possible.

Leave things and every worthy item,

defend your person with this Art,

and you will have honour and glorious insignia.

Oh, how a good and praise-deserving thing it is

to learn this Art that asks so little

and one thousand times gifts you with life.

Oh, in how many ways it can be useful

(troubles are found without looking for them,

happy is he who can put out another’s fire)

My Art, new and made with reason,

I speak not of the old one, which I leave

to our ancestors, along with their opinion.

If you don’t want to be of honor deprived,

measure your time and that of the partner:

this is the Art’s foundation, and its step.

Open your ears to the great document

and be sure to understand the beautiful reasons,

and so do not cause your teacher’s complaint.

(NOTE: another possible interpretation is: so you won’t be

deluded from your teacher)

Make sure that swords are sisters,

when you have to fence against someone,

and then choose the one you want.

Do not give anyone the sword’s advantage,

or you would risk being shamed;

this should be followed by everyone.

Good eye, knowledge, dexterity are needed,

and if you have both heart and strenght,

you will be a problem for anyone.

Understand well my sentence:

the larger man uses a long sword,

the small man uses a shorter one.

A man of great strenght breaks the guards,

but natural cleverness restrains that,

and gives courage to the small man.

He who knows many strokes brings poison with him,

he who knows little encounters many troubles,

and in the end is conquered.

And if you understand well what I am saying,

and grasp the reason of this Art,

then she will keep you out of troubles.

Be well aware of what the speech puts here :

Do not show the secrets of the Art,

or you will be hurt for this reason.

Also note well this other part:

the longer sword is deadly,

you cannot face it without being in danger;

Be sure that it is equal to the measure,

as I said in the first chapter

of our book, looking back.

I esteem only the two handed sword,

and only it I use when I’m in need,

as I write in rhyme in my book.

And if you are not looking for shame,

do not tackle with several foes:

you will not make a good sound.

(NOTE: the original translation is difficult, and reads something

like “you will play a sound other than a bagpipe’s”)

If you are obliged to have something to do

with more than one, keep in your mind

to take a sword that you can well use.

You will take a light weapon and not a heavy one,

to easily control all of it,

to avoid being hindered by heavy weight.

Then you have to take a different way,

you should leave thrusts

and use other strokes to come back here,

as you will hear in my sentence.

Chapter 5

Of Thrusts and Cuts

Let the sword be a point with two edges,

but note and understand this writing,

to prevent your memory from failing:

one be the false, the other the true one,

and reasons commands and wants you

to keep this well in your mind:

deritto with true edge goes,*

riverso with the false edge stays,

except for fendente, which wants the true edge.**

Understand well my writing:

the sword stikes in seven ways,

that means six cuts and a thrust.

So that you find this way,

two up, two down and two in the middle.

The thrust in the middle with deceit and sorrow,

often clears our sky.***

*“deritto” is equivalent to “dritto”,

a right to left cut, Vadi uses both as well as “diritto”.

**Note: Vadi does not distinguish between different angles of cut;

all descending cuts are fendenti.

***Note: with this expression Vadi means that the thrust can often

get you out of trouble.

Chapter 6

The Seven Strokes of the sword

We are fendenti and we do question,

of often cleaving and cutting with sorrow

head and teeth in a straight way,

and every low guard

with our talent often we break ,

easily passing the one and the other.

(Note: meaning “all of them”)

Our strokes leave bloody marks,

and if we mix with rota

of all the Art we’ll our support.

Fendente, we bring the fear of wounds,

we come back in guard from passage to passage,

note that we are not slow to wound.

I am the rota and I have in me such strength,

if I mix with other strokes:

that I’ll often notch the arrow.

(Note: meaning to be dangerous).

I can not use loyalty and courtesy,

rotating I pass trough straight fendente

without hesitation I ruin arms and hands.

People gives me the name rota,

I look for the sword’s falsità,*

I sharpen the mind of he who uses me.

We are volanti and we always go crosswise,

from knee upwards we wound,

we are often banished by fendente and punte.

Across us without failing goes

the upwards striking rota,

and with fendente warms our cheeks.

*Note: the Italian word is “falsità”, and is

interpreted as referring to the false edge, according to the diagram,

but this word may also mean falsehood, and perhaps this is to be preferred,

considering the previous phrase. Also, while Chapter 6 is titled the

“Seven Cuts” , Vadi only lists three (fendente, volanti,

and rota), but as each of these can be employed either left or right,

along with punte (the thrust) they make for seven attacks.

Chapter 7

Of the Punta (thrust)

I am she who question all the strokes,

and I'm called the punta:

I am venomous as the scorpion;

and I feel strong, daring and ready,

I often cause the changing of stances

when somebody uses me in combat

and when I arrive my touch means harm.

Chapter 8

Of Cuts and Thrusts

It is said to use the rota with fendente and volante

against the ponte (thrusts) and so it is shown that these are

not so dangerous. And when they come at our presence, all blows make

them lose their way, losing also the chance to strike. The sword’s

stroke does not change direction, and so the punta has little

value against he who turns, but the blows open their way as they go.

If you have not a weak memory, remember that if the punta does

not hit, it loses its burst, and then all other blows are good to

defend. Against one foe the thrust finds good use, and against many

no more does its duty.*

*Note: it is unclear if he is referring to the number of enemies

or of blows, also the last part seems to be there only for rhyme.

If punta turns into rota do not fear: if it takes not at once

a good fendente, it remains without fruit, in my opinion. Keep

here your mind for awhile: if punta enters and does not exit

quickly, your enemy will sorely strike back. If with a cutting blow

your sword’s point loses its way, your sword is dead, unless

croce di sotto helps you.* A straight fendente I will

strike with my sword, and I will pull you out of your stance, so that

you go in a poor direction. Do not lose an hour to learn the long

times with the serene hand, it puts you over the others and honors

you.

Break every low stance. Low stances resist only weak loads, and so

the heavier break them easily. A heavy weapon does not pass quickly

in the opening, a light one comes and goes as an arrow with the bow.

*Note: a stance of Chapter 9.

Chapter 9

Of the Cross

I am the cross with the name of Jesus, in front and back I go,

to find many more defenses.

If I meet another weapon I do not lose my way, so strong am I;

and this often happens, as I search for it.

And when a long weapon finds me, he who with reason uses my defense,

will have the honor of every enterprise.

Chapter 10

Of the Mezza Spada

Being willing to follow this good writing,

it is necessary to declare part by part

all the strokes of the Art.

To properly understand and use,

reason wants that firstly I reveal to you the rotare* ,

principle of the sword.

Go with outstretched arms,

bringing the edge in the middle of your partner.

And if you want to seem great in the Art,

you then can go from guard to guard,

with serene and slow hand,

with steps niether long nor short.

If you do any stramazzone,*

do this with little turn before the face.

Do not do a move too wide

as a long time is lost.

Help yourself with the reverso,

moving out of the way with the left foot,

pulling the right also,

with the eye always to the good parare.***

When you will want to close in mezza-spada,

as your enemy pulls back his sword,

then do not hesitate the time you take you will pay for dearly.

Be in guardia de cenghiaro (boar’s stance)

when you thrust at the face,

do not remain too far, soon turning to the roverso fendente

and the deritto being sure to remember.

To be sure you can understand my goal

with clear reason, I hope to show you the way:

I do not want all this to be pure riverso

nor fendente, but between the one and the other

lies the common one striking the head from every side.

And I advise you, when you are close in,

set your legs paired,

you will surely be lord,

able to close and strike valiantly.

And when you strike with the reverso fendente,

bend your left knee and, noting this writing,

extend the right foot

without then changing sides.

Then, if under attack

now at the left foot or the head,

because they are closer

than the right, which remains sideways,

then you are sure from each side

and if you want to strike with a diritto fendente,

you should take

the right knee and well extend the left one.

The head will be attacked also

with the right foot that is nearer to it:

this is a better footwork

than the stepping of our elders.

Nobody should contrast or speak,

as you are stronger and more confident,

and hard while defending,

and quicker to make war,

nor they can bring you to the ground.

* Note: The word rota (“turning”) comes from the

verb “rotare”, which means “to turn”.

** Note: A problem here is that while “stramazzone”

is a technical term, i.e. it has no other meaning besides the stroke

described, words like “rota”, “volta”,

“molinello” have their own meaning beside the technical

application (such as “turn” “rotate” “whirl”),

so we cannot always identify a specific word with a specific technique.

*** Note: Vadi advises to parry with the fendente (downward cut),

definitely not a static block.

Chapter 11

Reason of Sword Play

Once you have closed to mezza spada,

with diritto or roverso,

understand the sense

of what I tell you about this point:

if you are there, keep ready your eye

make a swift feint with coverta

and hold your sword upright,

the arms playing over your head.

I cannot say this with few words,

because the effects are of mezza spada.

For your pleasure,

when you prefer, parare with fendente,

carefully push your sword a little away

from you, pressing down that of your compagno.

You will also get a good deal

by parrying well all the strokes.

When you parare the riverso, move forward

you right foot and parry as said,

when parrying the diritto

then you will move forward the left foot.

And you need to have the mind

ready when you strike the riverso fendente,

and a careful eye, to prevent

the mandritto coming from below.

And if your compagno should strike, you should

parry suddenly and make a move at his head

with the fil falso (“false edge”) and, with cunning,

as he rises, strike with the good reverso upwards,

quickly doubling with the deritto.

And note this also:

do not contradict the Art’s reason

if you strike with diritto; then beware

from being hit from his manreverso.

Make sure that your sword is

parrying with fendente, so that he hits you not,

and if you want

to close from below and grasp his handle

then do your duty

hammering with pommel his mustache,

being careful not to get into troubles.

Chapter 12

Reason (principles) of Sword Feints

Again I advise you to have care to what I say,

that when you have closed at mezza spada

you can act well from each side,

following the Art with good viste (“feints”).

The viste mean confusion,

which confuses the other in defense,

so he cannot understand

from which side you will act.

I can not show you this very well

with my words, as I could do with a sword;

so use your mind

to study the Art in my words,

and you will acquire courage through reason.

As I advise and teach you,

To follow what I write in these many verses,

to find the deep and the shore of this Art.

Chapter 13

Reason (principles) of Mezza Spada (play)

Having closed to half-sword,

you can well hammer more and more times,

hitting from one side only

(your feints should go on the other side),

and as he loses, parrying, his way,

you should hammer on the other side;

then you should evaluate

which blow to use for winning.

And if you want to strike blows,

let go the fendente roverso,

turning through

and false edge with the point at the face.

Do not get divided from him,

with riverso or dritto again,

work with the one you like,

provided that knees bend on each side,

as I have shown you above.

I add this also:

always enter with the point,

rising upwards to the face,

and use your blows when the time is right.

Chapter 14

Reason (principles) of sword Half Time

I can not, in writing, show you,

the principle of half time, and the way,

because in the knot* remains

the shortness of the time and of its use.

The half time is only a turn

of the knot, a quick and immediate strike.

It can seldom fail

when it is done with good measure;

and if you note my writing,

he who lacks practice divides not well:

often the blow

breaks with good edge the other’s brain.

Of all the Art this is the jewel,

because at once it strikes and parries.

Oh, it is so precious a thing,

to practice it with good reason,

as it lets you bear the Art’s banner.

*Note: The translation is literal. Bascetta suspected it related

to the hand position, citing Manciolino; or else, he thinks it can

be the crossing point of the swords.

Chapter 15

Principles of the sword against the Rota

There are many who base themselves

in rotating strongly from each side;

but be sure to be warned

as he rotates his sword,

rotate your own, and you will win the tests.

Match yourself with him in striking,

and be sure to go

with your sword after his.

To make this clearer to your mind,

you can go in boar's tooth,

and if he rotates,

you also rise from low to high.

Hear and understand my principles, you

who are new to the art or expert too,

I want you to be sure

that this is the true Art and Science.

Consider that, for a scale’s line

the compagno will be in porta di ferro (“Iron

Door”),

this I put in your heart,

be in posta sagitaria (“Archer’s guard”).

Be sure that your point does not sway,

that of the compagno covering the sword,

go slightly out of the way

straightening up sword and hand with the point.

When your sword has come at the cross,

then do the thirteenth closing technique,

as you see it well

painted in our book with seven papers.

You can also use in this art

strokes and close techniques that you find simpler;

leave the more complex,

take those favoring your side

and often you will have honour in the Art.

Chapter 16

Sword Teachings

Your sword should be like

a shield which covers you all.

Now take this fruit,

which I give you for your mastery.

Be sure that your sword never be,

striking or guarding, far from you.

Oh, how a good thing it is

to have your sword doing a short run.

Your point should be directed in the face

of the compagno, in guards or while striking;

you will take away his courage,

seeing always the point in front of him.

And you will do your play always in front,

with your sword and with small turning,

with serene and agile hand,

often breaking the compagno’s time,

you will weave a web well different from a spider’s.

Vadi’s Guards:

Mezana porta di ferro - “I am the strong middle iron

door, to give death with cuts and thrusts.”

Posta di donna - “I am the woman’s stance and I

am not useless, because the sword’s length often deceives."

Porta di ferro - “I am the low iron door, that always

hinders cuts and thrusts”

Posta di falcon - Falcon

Posta di vera finestra - "I am the stance of true window...

of the Art left tight.”

Posta corona - “I am the crown and I am master, in bindings

I am skilled.”

Vadi's Blows:

These are the blows of the two handed sword.

There is not the half time: it remains in the knot.

I am the rota and I often go turning

I am looking for the sword’s false.

We are volanti ever going crosswise

from the knees up we go wounding.

We are fendenti and we do question

of cutting teeths with straight reason.

I am ponta dangerous and quick

of all the blows I am the highest master.

|