|

The

Weighty Issue of Two-Handed Greatswords The

Weighty Issue of Two-Handed Greatswords

By J. Clements

"never

overlay thy selfe with a heavy weapon, for nimblenesse of bodie,

and

nimblenesse of weapon are two chief helpes for thy advantage"

- Joseph Swetnam, 1617

The Schoole of the Noble and Worthy Science of Defence

Popular media, fantasy games, and uninformed historians frequently

give the impression that these immense weapons were awkward, unwieldy

and ponderously heavy. The facts confirm an entirely different

understanding.

Identification - Definition of the Two-Handed Great Sword

To understand what we are discussing it is important to first have

a working definition. The respected work, Swords and Hilt Weapons,

offers this description of the weapon:

"The

two-handed sword was a specialized and effective infantry weapon,

and was recognized as such in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Although large, measuring 60-70 in/150-175 cm overall, it was not

as hefty as it looked, weighing something of the order of 5-8 lbs/2.3-3.6

kg. In the hands of the Swiss and German infantrymen it was lethal,

and its use was considered as special skill, often meriting extra

pay. Fifteenth-century examples usually have an expanded cruciform

hilt, sometimes with side rings on one or both sides of the quillon

block. This was the form which remained dominant in Italy during the

sixteenth century, but in Germany a more flamboyant form developed.

Two-handed swords typically have a generous ricasso to allow the blade

to be safely gripped below the quillons and thus wielded more effectively

at close quarters. Triangular or pointed projections, known as flukes,

were added at the base of the ricasso to defend the hand." (Coe et

al, p. 48) "The

two-handed sword was a specialized and effective infantry weapon,

and was recognized as such in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

Although large, measuring 60-70 in/150-175 cm overall, it was not

as hefty as it looked, weighing something of the order of 5-8 lbs/2.3-3.6

kg. In the hands of the Swiss and German infantrymen it was lethal,

and its use was considered as special skill, often meriting extra

pay. Fifteenth-century examples usually have an expanded cruciform

hilt, sometimes with side rings on one or both sides of the quillon

block. This was the form which remained dominant in Italy during the

sixteenth century, but in Germany a more flamboyant form developed.

Two-handed swords typically have a generous ricasso to allow the blade

to be safely gripped below the quillons and thus wielded more effectively

at close quarters. Triangular or pointed projections, known as flukes,

were added at the base of the ricasso to defend the hand." (Coe et

al, p. 48)

In

contrast to longswords, technically, true two-handed swords (epee's

a deux main) or "two-handers" were actually Renaissance, not

Medieval weapons. They are really those specialized forms of the later

1500-1600s, such as the Swiss/German Dopplehänder ("double-hander")

or Bidenhänder ("both-hander"). The popular names Zweihander

/ Zweyhander are actually relatively modern not historical

terms. English ones were sometimes referred to as "slaughter-swords"

after the German, Schlachterschwerter ("battle swords").

While used similarly to longswords, and even employed in some duels,

they were not identical in handling or performance. No major historical

teachings detailing fencing with these specific weapons are known.

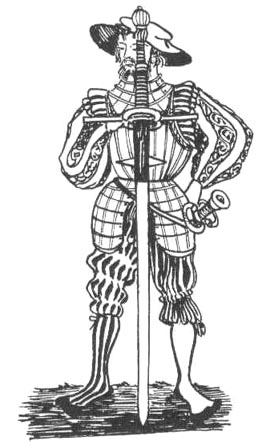

These weapons were used primarily for fighting among pike-squares

where they would hack paths through knocking aside poles, possibly

even lobbing the ends off opposing halberds and pikes then slashing

and stabbing among the ranks. Wielded by the largest and most impressive

soldiers (Doppelsoldners, who received double pay), they

were also used to guard banners and castle walls. The Italian humanist

historian Paulus Jovius writing in the early 1500s also described

the two-hand great sword as being used by Swiss soldiers to chop the

shafts of pikes at the battle of Fornovo in 1495. In

contrast to longswords, technically, true two-handed swords (epee's

a deux main) or "two-handers" were actually Renaissance, not

Medieval weapons. They are really those specialized forms of the later

1500-1600s, such as the Swiss/German Dopplehänder ("double-hander")

or Bidenhänder ("both-hander"). The popular names Zweihander

/ Zweyhander are actually relatively modern not historical

terms. English ones were sometimes referred to as "slaughter-swords"

after the German, Schlachterschwerter ("battle swords").

While used similarly to longswords, and even employed in some duels,

they were not identical in handling or performance. No major historical

teachings detailing fencing with these specific weapons are known.

These weapons were used primarily for fighting among pike-squares

where they would hack paths through knocking aside poles, possibly

even lobbing the ends off opposing halberds and pikes then slashing

and stabbing among the ranks. Wielded by the largest and most impressive

soldiers (Doppelsoldners, who received double pay), they

were also used to guard banners and castle walls. The Italian humanist

historian Paulus Jovius writing in the early 1500s also described

the two-hand great sword as being used by Swiss soldiers to chop the

shafts of pikes at the battle of Fornovo in 1495.

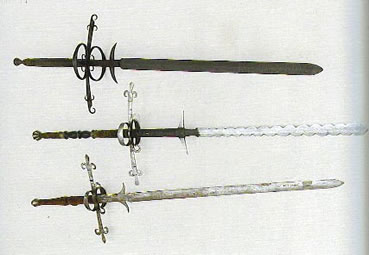

Many

of these weapons have compound-hilts with side-rings and enlarged

cross-guards of up to 12 inches. Most have small, pointed lugs or

flanges protruding from their blades 4-8 inches below their guard.

These parrierhaken or "parrying hooks" act almost as a secondary

guard for the ricasso to catch and bind other weapons or prevent them

from sliding down into the hands. They make up for the weapon's slowness

on the defence and can allow another blade to be momentarily trapped

or bound up. They can also be used to strike with. Certain wave or

flame-bladed two-handed swords have come to be known by collectors

as flamberges, although they are more appropriately known as flammards

or flambards (the German, Flammenschwert). The wave-blade

form is visually striking but really no more effective in its cutting

than a straight one. There were also huge two-handed blades known

as "bearing-swords" or "parade-swords" (Paratschwert), weighing

up to 10 or even 15 pounds and which were intended only for carrying

in ceremonial processions and parades. Many

of these weapons have compound-hilts with side-rings and enlarged

cross-guards of up to 12 inches. Most have small, pointed lugs or

flanges protruding from their blades 4-8 inches below their guard.

These parrierhaken or "parrying hooks" act almost as a secondary

guard for the ricasso to catch and bind other weapons or prevent them

from sliding down into the hands. They make up for the weapon's slowness

on the defence and can allow another blade to be momentarily trapped

or bound up. They can also be used to strike with. Certain wave or

flame-bladed two-handed swords have come to be known by collectors

as flamberges, although they are more appropriately known as flammards

or flambards (the German, Flammenschwert). The wave-blade

form is visually striking but really no more effective in its cutting

than a straight one. There were also huge two-handed blades known

as "bearing-swords" or "parade-swords" (Paratschwert), weighing

up to 10 or even 15 pounds and which were intended only for carrying

in ceremonial processions and parades.

Dr.

Hans-Peter Hils in his 1985 dissertation on the work of the great

14th century master Johannes Liechtenauer noted that since the 19th

century many arms museum collections typically feature immense parade

or bearing greatswords as if they were actual combat weapons ignoring

the fact they are not only blunt edged, but of impractical size and

weight as well as poorly balanced for effective use. (Hils, p. 269-286).

Though never intended for actual fighting, examples of such ponderous

specimens are still occasionally cited incorrectly as having been

actual combat weapons. Dr.

Hans-Peter Hils in his 1985 dissertation on the work of the great

14th century master Johannes Liechtenauer noted that since the 19th

century many arms museum collections typically feature immense parade

or bearing greatswords as if they were actual combat weapons ignoring

the fact they are not only blunt edged, but of impractical size and

weight as well as poorly balanced for effective use. (Hils, p. 269-286).

Though never intended for actual fighting, examples of such ponderous

specimens are still occasionally cited incorrectly as having been

actual combat weapons.

One source tells us that among 16th century armies the adoption of

the two-handers was very limited and in comparison with the pike or

the halberd did not play a meaningful role. “In the infantry

unit, the German and Swiss Landsknechts positioned the Doppelsöldner

(Soldiers who received double pay for wielding the two-handers) in

the front ranks for a long time to strike down the opposing pikes

and to hack out breaches into which one's own soldiers could penetrate.

However it would become unusable, as soon as the opposing forces collided

with one another, and there would be increased pressure from the back

ranks onto the front ranks, which created a thick melee.”

Thus, “sometime around the middle of the 16th century it (the

two-hander) disappeared from war and mutated into a form of guard

and ceremonial weapon with a symbolic character.” (Kamniker

and Krenn, p. 130).

As

one writer says of the weapon, "Among the smaller countries where

mercenary bands were likely to develop---the Low Countries, the Italian

city states, and the free cities and states of the German lands---the

Swiss became premier two-handed swordsmen for hire from the 14th century

until well into the 16th century. The two-handed sword and the multipurpose

polearm, called the halberd, were familiar Swiss trademarks. The Swiss

and Germans made their own two-handed swords. The Italians made a

basic two-hander that they exported throughout Europe. Two-handed

swordsmen were perimeter shock troops, trained to lay into approaching

knights or infantry and break their stride. By the end of the 15th

century, however, the Swiss had turned almost exclusively to the 17-

to 18-foot pike as their weapon of choice, becoming the premier pikemen

of Europe. The two-handed sword was considered incompatible with the

pike and was actually outlawed as a frontline weapon by many confederation

members--though the Swiss kept making them. The two-hander remained

a popular weapon among many other European mercenaries, in Italy and

particularly in Germany." (William J. McPeak. "For a Swordsmen with

Muscle as Well as Skill, Two Hands Could be Better Than One."

Military History, Oct 2001, Vol. 18. Issue 4, p 24). As

one writer says of the weapon, "Among the smaller countries where

mercenary bands were likely to develop---the Low Countries, the Italian

city states, and the free cities and states of the German lands---the

Swiss became premier two-handed swordsmen for hire from the 14th century

until well into the 16th century. The two-handed sword and the multipurpose

polearm, called the halberd, were familiar Swiss trademarks. The Swiss

and Germans made their own two-handed swords. The Italians made a

basic two-hander that they exported throughout Europe. Two-handed

swordsmen were perimeter shock troops, trained to lay into approaching

knights or infantry and break their stride. By the end of the 15th

century, however, the Swiss had turned almost exclusively to the 17-

to 18-foot pike as their weapon of choice, becoming the premier pikemen

of Europe. The two-handed sword was considered incompatible with the

pike and was actually outlawed as a frontline weapon by many confederation

members--though the Swiss kept making them. The two-hander remained

a popular weapon among many other European mercenaries, in Italy and

particularly in Germany." (William J. McPeak. "For a Swordsmen with

Muscle as Well as Skill, Two Hands Could be Better Than One."

Military History, Oct 2001, Vol. 18. Issue 4, p 24).

|

|

Answering the Weight Question - how much did the actual historic

weapons really weigh?

Nothing

answers the question of genuine weight better than sample evidence

of actual historical specimens. Sword collector and author Dr. Lee

Jones possesses a very fine specimen of a 16th century German two-handed

great sword, that this author had the privilege of exercising outdoors

with, had length in excess of five feet and a weight of 7.9 pounds

(3490g), but handled easily with superb balance. Curator of arms for

the Hungarian Military History Museum in Budapest, László Töl, describes

a very fine specimen of another 16th century German two-handed great

sword of 53.4 inches length, which this author also had the privilege

of examining, as weighing only a little over 8 pounds. Again,

the piece's size and weight betrayed a functional and well-balanced

weapon. László Töl adds: "The full length of the sword is 1808 mm,

the full length of the blade is 1355 mm, the edge of the blade is

936 mm long, the length of the hilt is 306 mm, and the diameter of

the cross-guard is 502 mm. The width of the blade is 46 mm, and its

thickness is 7.5 mm. The 'neck' of the blade is 8.6 mm thick and 32

mm wide. The centre of gravity is 616 mm from the pommel. The sword

weighs 3650g. The blade's cross-section is rhomboid in shape." Nothing

answers the question of genuine weight better than sample evidence

of actual historical specimens. Sword collector and author Dr. Lee

Jones possesses a very fine specimen of a 16th century German two-handed

great sword, that this author had the privilege of exercising outdoors

with, had length in excess of five feet and a weight of 7.9 pounds

(3490g), but handled easily with superb balance. Curator of arms for

the Hungarian Military History Museum in Budapest, László Töl, describes

a very fine specimen of another 16th century German two-handed great

sword of 53.4 inches length, which this author also had the privilege

of examining, as weighing only a little over 8 pounds. Again,

the piece's size and weight betrayed a functional and well-balanced

weapon. László Töl adds: "The full length of the sword is 1808 mm,

the full length of the blade is 1355 mm, the edge of the blade is

936 mm long, the length of the hilt is 306 mm, and the diameter of

the cross-guard is 502 mm. The width of the blade is 46 mm, and its

thickness is 7.5 mm. The 'neck' of the blade is 8.6 mm thick and 32

mm wide. The centre of gravity is 616 mm from the pommel. The sword

weighs 3650g. The blade's cross-section is rhomboid in shape."

A

15th century two-handed Federschwert (practice sword) of

51.5 inches in length now at the Swiss National Landesmuseum weighs

in at only 3.12lbs (1.415kg). Another warsword there of 48 inches

in length weighs 4.63lbs (2.10kg), and an acutely tapered one of a

length of 46.7 inches weighs in at only 3.018lbs (1.369kg). By comparison,

a single-hand sword of 38-inches in the same collection weighed 3.28lbs

(1.495kg). A

15th century two-handed Federschwert (practice sword) of

51.5 inches in length now at the Swiss National Landesmuseum weighs

in at only 3.12lbs (1.415kg). Another warsword there of 48 inches

in length weighs 4.63lbs (2.10kg), and an acutely tapered one of a

length of 46.7 inches weighs in at only 3.018lbs (1.369kg). By comparison,

a single-hand sword of 38-inches in the same collection weighed 3.28lbs

(1.495kg).

The author has handled two-handed greatswords at the British Royal

Armouries in Leeds that were distinctly identifiable as fighting weapons.

The current curator of European edged weapons, Robert C. Woosnam-Savage,

at the Royal Armouries writes:

"The fighting two-handed sword, weighed (on average)

between 5-7 lbs. I give the following three examples, randomly chosen

from our own collections, which I hope are adequate to make the

point:

Two-handed sword, German, c.1550 (IX.926). Weight:

7 lb 6oz.

Two-handed sword, German, dated 1529 (IX.991). Weight:

5 lb 1oz.

Two-handed sword, Scottish, mid 16th century, (IX.926).

Weight: 5 lb 10oz.

|

A

40-Pound Sword?

By

C. Jarko

One

of the most outrageous (and wildly incorrect) statements made

about Medieval swords is that they were heavy and weighed

as much as 40 pounds. While the fact that this statement

even came once from a respected scholar and expert on Medieval

warfare is surprising, it's not at all an uncommon claim.

Let's take a look at just how large a sword would have to

be to weigh that much or anywhere close to it.

Simple

Science (with a little algebra thrown in): How do

we know Medieval swords weren't 40 pounds (or for that matter,

even 15 or 20 pounds)? The answer is density.

Density is a way of expressing how much an object (of

a certain size and of a given material) weighs.

The size of the object is expressed in terms of its volume.

Volume is the size of an object as measured by its length,

width and thickness (or height) and is expressed in cubic

inches. Written as a mathematical equation,

it looks like this:

V

= L x W x H.

One

cubic inch is one inch long by one inch wide by one inch thick.

For

the purpose of this discussion, we can use a simple three-dimensional

rectangle to represent our sword. Let's pick a typical

longsword with an overall length of 48 inches and a general

width of 2 inches (the widest part of the blade). We'll

get to the height later.

Swords

were made of carbon steel, which has a known density of roughly

0.284 pounds per cubic inch (lbs/per cubic inch). If

we know how much weight we have (in this case "40" pounds),

we can figure out how many cubic inches the object would have:

40

pounds divided by 0.284 (the density of steel) = 140.85 cubic

inches (the volume or "V" of a 40 pound sword).

Our

sword is 48 inches long, 2 inches wide and "H" inches thick,

thus: V = 48 x 2 x H. Using our volume of 140.85, we

can solve for H for which we get:

140.85

= 48 x 2 x H

140.85

= 96 x H

H=

1.47 inches (140.85 divided by 96)

This

means our steel sword is 48 inches long, 2 inches wide and

1.47 inches thick along its entire length.

This would definitely be a blunt object and not a sharp cutting

instrument like a sword.

Just

for fun, let's see what we get when we say a sword (again

48 inches long and 2 inches wide) weighs 15 pounds or 10 pounds:

15

pounds divided by 0.284 (the density of steel) = 52.82 cubic

inches (the volume "V" of a 15 pound sword).

Using

our volume of 52.82, we can solve for H:

52.82

= 48 x 2 x H

52.82

= 96 x H

H

= 0.55 inches (52.82 divided by 96)

That's

over half an inch thick, still a blunt object. Let's

try one more time for 10 pounds.

10

pounds divided by 0.284 (the density of steel) = 35.21 cubic

inches (the volume "V" of a 15 pound sword).

Again,

we can solve for H:

35.21

= 48 x 2 x H

35.21

= 96 x H

H

= 0.37 inches

That's

almost three eighths of an inch thick. If you look at

three eighths of an inch on a ruler, you'll see we are now

starting to get "sword-like" but we're still not there.

If

we do the math using the thickness of a real sword (say

an average 1/8th inch thick across a roughly 48" by 2" rectangle)

it turns out such it weighs a reasonable 3.408 pounds. Which,

when you take into account things like differential cross-section,

distal taper, edge bevel and overall taper of the blade geometry,

as well as the weight of the pommel and cross, then an average

weight of 2.5 - 3.5 pounds works out just about right. So,

the next time

When

someone says "a longsword weighs 15 pounds", you can reply,

"Oh, like this?" as you hand them 15 pounds of a half-inch

thick steel slab four feet long and two inches wide. There's

nothing like holding the truth in your hands. If there were

really battle swords that actually weighed 40 pounds, or even

just 15 or 20 pounds, then where are they? Why don't

we have a single historical example as proof? It would

be such an easy thing to prove. So, if you have a modern

made sword which you bought and it weighs far more than the

real life working versions of history, no matter what the

manufacture claims, that sword is just not made correctly.

When

we use the mathematical proof, we need to understand that

there are variables which we aren't taking into account here,

but this line of argument works well enough to debunk the

more outrageous claims about sword weight. The next

time you're arguing with someone who refuses to budge off

their claim that swords were very heavy and unwieldy, you

can tell them: "Hey, you do the math!"

An

ordinary exercise bar (available at most large sporting goods

stores) is an excellent way to demonstrate how real swords

were not "heavy." These 50" poles come in 9, 12, and

14 pound versions and comparing the heft of such weight to

a sword blade makes it very clear how absurd a weapon of such

mass would be.

|

Arms authority, David Edge, former head curator and current conservator

of the famed Wallace Collection museum in London, similarly states

for us:

"I very recently had occasion to handle a couple of similar-sized

hand-and-a-half 16th-century 'heading' swords in the [Wallace] Collection…one

undoubtedly genuine (#A721) and one now thought to be a Victorian

fake (A723), albeit not described as such in the 1962 [Wallace Collection]

catalogue. The two swords handled completely and

dramatically differently…on checking their weights the genuine

one weighed 3 lbs. 12 oz., and felt like it could take a head off

with ease, while the fake weighed in at an unwieldy 5lbs 3 oz. and

to wield felt more like an iron bar intended to bludgeon the unfortunate

prisoner to death! Clearly making replica swords too heavy

is not the sole prerogative of modern manufacturers…Victorian

copyists appear sometimes to have fallen into the same trap!

It is interesting to compare these weights with that of a double-handed

fighting sword of similar date…for example, our Landsknecht

double-hander #A470, the one with a wavy blade. This (a much

larger sword all round) still only weighs a mere 7 lbs. 4 oz."

"Original

weapons are indeed far lighter than most people realize …3

lbs for an 'average' late-medieval cross-hilt sword, say, and 7-8

lbs for a Landsknecht two-handed sword, to give just a couple of

examples from weapons in this collection. Processional two-handed

swords are usually heavier, true, but rarely more than 10 lbs.

The heaviest and most enormous sword in our entire Armoury only

weighs 14 lbs and was probably ceremonial." "Original

weapons are indeed far lighter than most people realize …3

lbs for an 'average' late-medieval cross-hilt sword, say, and 7-8

lbs for a Landsknecht two-handed sword, to give just a couple of

examples from weapons in this collection. Processional two-handed

swords are usually heavier, true, but rarely more than 10 lbs.

The heaviest and most enormous sword in our entire Armoury only

weighs 14 lbs and was probably ceremonial."

ARMA consultant Henrik Andersson of the Livrustkammaren,

Swedish Royal Armoury of Stockholm, provides a table with the following

measurements on two-handed and greatswords in the collection there.

The author and his colleagues have handled several of these pieces:

Two-handed sword. No: LRK 13639.

Swedish, c1658

Length: 1010 mm (39.7 inches)

Blade: 862 mm (33.9 inches)

Weight: 1735 g (3.47 pounds) |

Ceremonial Two-handed sword.

No: LRK 5666.

Swedish, c1658.

Length: 1025 mm (40.3 inches)

Blade: 933 mm (36.7 inches)

Weight: 1590 g (3.18 pounds) |

Two-handed sword. No: LRK 12959.

Solingen, Early 17th century.

Length: 1350 mm (56.2 inches)

Blade: 961 mm (37.8 inches)

Weight: 3010 g (6.2 pounds) |

Two-handed sword. No: LRK 16660.

German, 17th century.

Length: 1428 mm ( inches)

Blade: 1048 mm ( inches)

Weight: 2730 g (5.46 pounds) |

Two-handed sword. No: LRK 16662.

German, Late 16th century.

Length: 1790 mm (70.4 inches)

Blade: 1250 mm (49.2 inches)

Weight: 4630 g (9.26 pounds) |

One-and -a-half-handed sword.

No: LRK 10972.

Southern German, c1550.

Length: 1252 mm ( inches)

Blade: 1019 mm ( inches)

Weight: 1500 g (3 pounds) |

Two-handed sword. No: LRK 12947.

German, 16th century.

Length: 1185 mm (46.6 inches)

Blade: 954 mm (37.5 inches)

Weight: 1240 g (2.48 pounds) |

Two-handed sword. No: LRK 12667.

German, 16th century.

Length: 1225 mm (48.2 inches)

Blade: 904 mm (35.5 inches)

Weight: 1310 g (2.62 pounds) |

One-and -a-half-handed sword.

No: LRK 12913.

Probably German, c. 1350

Length: 1170 mm (46 inches)

Blade: 829 mm (32.6 inches)

Weight: 1280 g (2.56 pounds) |

Two-handed sword. No: LRK 12716.

German, c1500.

Length: 1340 mm (52.7 inches)

Blade: 955 mm (37.6 inches)

Weight: 1390 gr\ (3 lbs) |

One-and -a-half-handed sword.

No: LRK 12711.

German, c1475-1525.

Length: 1153 mm (45.3 inches)

Blade: 932 mm (36.6 inches)

Weight: 1320 g (2.9 lbs) |

Ceremonial Two-handed sword.

No: LRK 6362.

German (probably Passau) c1600.

Length: 1275 mm (50.1 inches)

Blade: 1000 mm (39.37inches)

Weight: 2330 g (5.1 lbs) |

Ceremonial Two-handed sword.

No: LRK 16370.

German. Late 16th century.

Length: 1422 mm (55.9 inches)

Blade 1029 mm (40.5 inches)

Weight: 2700 g (5.9 lbs) |

Ceremonial Two-handed sword.

No: LRK 6956.

Brunswick type. German. Late 16th century.

Length: 1893 mm (74.5 inches)

Blade: 1313 mm (51.7 inches)

Weight: 4830 gr (10.6 lbs) |

Ceremonial Two-handed sword.

No: LRK 6941.

Brunswick type. German. Late 16th century.

Length: 1817 mm (71.5 inches)

Blade: 1240 mm (48.8 inches)

Weight: 3970 g (8.75 lbs) |

Ceremonial Two-handed sword.

No: LRK 16371.

Brunswick type. Munich, c1550-1575.

Length: 1643 mm (64.7 inches)

Blade: 964 mm (37.9 inches)

Weight: 3500 g (7.7 lbs) |

Two-handed sword. No: LRK 12706.

German. Late 15th century.

Length: 1473 mm (58 inches)

Blade: 1066 mm (41.9 inches)

Weight: 2720 g (5.9 lbs) |

Two-handed sword. No: LRK 12715.

German, c1475-1525.

Length: 1382 mm (54.4 inches)

Blade: 1055 mm (41.5 inches)

Weight: 1550 g (3.4 lbs) |

Two-handed sword. No: LRK 5480.

Germany, 15th century.

Length: 1375 mm (54.2 inches)

Blade: 920 mm (36.2 inches)

Weight: 1600 g (3.5 lbs) |

|

Note that unlike ceremonial specimens, none of the fighting weapons

exceeded 4 pounds and the heaviest ceremonial was less than 11. The

catlog of the famous arsenal in Graz, Austria, contains similar weights

for its two-handed great sword specimens.

Historical

fencing researcher and author, Grzegorz Zabinski, observes, "It can

be assumed that the two-handed infantry swords were a culminating

point of one of the directions of the evolution of swords, that aimed

to increase their efficiency against plate by means of increasing

their dimensions and weight, and, quite naturally, their impact."

Zabinski offers sample data for a range of two-handed infantry swords

from the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th centuries at

the excellent collection of such weapons housed in the State Art Collection

at the Royal Castle of Wawel, Krakow, Poland: Historical

fencing researcher and author, Grzegorz Zabinski, observes, "It can

be assumed that the two-handed infantry swords were a culminating

point of one of the directions of the evolution of swords, that aimed

to increase their efficiency against plate by means of increasing

their dimensions and weight, and, quite naturally, their impact."

Zabinski offers sample data for a range of two-handed infantry swords

from the end of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th centuries at

the excellent collection of such weapons housed in the State Art Collection

at the Royal Castle of Wawel, Krakow, Poland:

Two-Handed Infantry Sword with parrying-hooks. No.

4434. Late 15th - early 16th century. Total length 167 cm (65.7

inches), total weight 3 kg (6 pounds), blade length 117 cm, hilt

length 50 cm, crosspiece length 34 cm. Blade's width at the shoulder

43 mm, at the parrying-hooks 36 mm, behind the parrying-hooks 50

mm, at the point 33 mm. Blade's thickness at the shoulder 11 mm.

Two-Handed Infantry Sword with parrying-hooks. No.

4435. Early 16th century. Total length 158 cm (62 inches), total

weight 3.10 kg (6.2 pounds), blade length 114.5 cm, hilt length

44 cm, crosspiece length 41.5 cm. Blade's width at the shoulder

33 mm, width at the point 58 mm. Blade's thickness at the shoulder

9 mm.

Two-Handed Infantry Sword with side-rings. No. 4437.Early

16th century. Total length 163 cm (64 inches), total weight 3.25

kg (6.5 pounds), blade length 125 cm, hilt length 38 cm, crosspiece

length 38 cm. Blade's width at the shoulder 53mm, at the point 30

mm. Blade's thickness at the shoulder 8 mm, at the point 2 mm.

Two-Handed Infantry Swordwith parrying-hooks. No.

4440. Late 15th - early 16th century. Total length 167 cm (65.7

inches), total weight 3 kg(6 pounds), blade length 122.2 cm (48

inches), hilt length 44.5 cm, crosspiece length 39 cm. Blade's width

at the shoulder 47 mm, at the point 26 mm. Blade's thickness at

the shoulder 7 mm, at the point 2 mm. The parrying-hooks: total

length 13.7 cm, pointed, width at the shoulder 1.5 cm.

Two-Handed Infantry Sword.National Museum Wroclaw.

No. IX-780. Late 15th - early 16th century. Total length 148 cm

(58 inches), total weight 2 kg (4 pounds), blade length 107.5 cm,

hilt length 39.8 cm, crosspiece length 31.3 cm. Blade's width at

the shoulder 38 mm, at the point 33 mm. Blade's thickness at the

shoulder 10 mm, at the point 4 mm.

Two-Handed Infantry Sword with parrying-hooks. National

Museum Wroclaw, No. IX-784. Early 16th century. Total length 164

cm (64 inches), total weight 2 kg (4 pounds), blade length 146.8

cm, hilt length 45.8 cm, crosspiece length 39.4 cm. Blade's width

at the shoulder 35 mm. Blade's thickness 10 mm at the shoulder,

2.5 mm at the point. The pommel's height (base included) 5.4 cm,

base's height 5 mm, pommel's diameter 5.4 cm.

Note

that of the samples here the heaviest is less than 7 and a half

pounds and one particularly large weapon of 58 inches weighs no

more than 4 pounds.

A practical explanation for the futility of especially

heavy weapons is that they are slow. In physics terms, doubling the

mass of a weapon can provide twice the strike energy, but doubling

the velocity of a strike provides four times the energy.

Below is a table of measurements from 69 two-handed great swords

from the 16th century in the famed Austrian arsenal of Graz (K. Kamniker

and P. Krenn, p. 139-152). Note that the average weight is less than

8 pounds at an average length of 67 inches. The weapons in the collection

range up to 5 pounds difference in their weight. The lightest weapon,

a slender blade, is just over than 3.3 pounds (at roughly 57 inches

long) while the heaviest, a large and elaborately hilted piece, is

no more than 13 pounds (at about 78 inches a long):

| Sword

Number |

Length

in cm |

Weight

in kg |

Length

in inches |

Weight

in pounds |

| 1 |

169 |

3.76 |

66.5 |

8.2 |

| 2 |

168 |

3.44 |

66.1 |

7.5 |

| 3 |

156 |

3.08 |

61.4 |

6.7 |

| 4 |

169 |

3.13 |

66.5 |

6.9 |

| 5 |

172 |

3.5 |

67.7 |

7.7 |

| 6 |

180.5 |

4.35 |

71.0 |

9.5 |

| 7 |

184 |

3.66 |

72.4 |

8.0 |

| 8 |

170.5 |

3.6 |

67.1 |

7.9 |

| 9 |

195.5 |

5.92 |

76.9 |

13.0 |

| 10 |

197 |

5.4 |

77.5 |

11.9 |

| 11 |

186.5 |

4.33 |

73.4 |

9.5 |

| 12 |

180.5 |

4.28 |

71.0 |

9.4 |

| 13 |

178 |

3.51 |

70.0 |

7.7 |

| 14 |

182 |

3.75 |

71.6 |

8.2 |

| 15 |

186 |

3.93 |

73.2 |

8.6 |

| 16 |

199 |

5.42 |

78.3 |

11.9 |

| 17 |

187.5 |

4.7 |

73.8 |

10.3 |

| 18 |

175.5 |

3.64 |

69.0 |

8.0 |

| 19 |

162 |

3.28 |

63.7 |

7.2 |

| 20 |

168.5 |

2.45 |

66.3 |

5.4 |

| 21 |

170.5 |

3.37 |

67.1 |

7.4 |

| 22 |

158.5 |

2.88 |

62.4 |

6.3 |

| 23 |

170.5 |

3.67 |

67.1 |

8.0 |

| 24 |

164.5 |

3.8 |

64.7 |

8.3 |

| 25 |

158 |

3.11 |

62.2 |

6.8 |

| 26 |

168.5 |

3.39 |

66.3 |

7.41 |

| 27 |

173.5 |

3.73 |

68.3 |

8.2 |

| 28 |

170.5 |

3.51 |

67.1 |

7.7 |

| 29 |

176.5 |

3.63 |

69.4 |

8.0 |

| 30 |

176 |

3.77 |

69.2 |

8.3 |

| 31 |

174.5 |

3.78 |

68.7 |

8.3 |

| 32 |

170 |

3.17 |

66.9 |

6.9 |

| 33 |

176 |

4.3 |

69.2 |

9.4 |

| 34 |

169 |

4.2 |

66.5 |

9.2 |

| 35 |

169 |

2.95 |

66.5 |

6.5 |

| 36 |

190 |

5.04 |

74.8 |

11.1 |

| 37 |

183 |

4.73 |

72.0 |

10.4 |

| 38 |

173 |

3.46 |

68.1 |

7.6 |

| 39 |

167 |

3.83 |

65.7 |

8.4 |

| 40 |

187 |

4.73 |

73.6 |

10.4 |

| 41 |

180.5 |

3.79 |

71.0 |

8.3 |

| 42 |

180.5 |

4.64 |

71.0 |

10.2 |

| 43 |

150 |

2.93 |

59.0 |

6.4 |

| 44 |

164.5 |

3.67 |

64.7 |

8.0 |

| 45 |

171 |

3.39 |

67.3 |

7.4 |

| 46 |

171.5 |

3.55 |

67.5 |

7.8 |

| 47 |

167.5 |

3.45 |

65.9 |

7.6 |

| 48 |

175.5 |

3.85 |

69.0 |

8.4 |

| 49 |

171 |

3.51 |

67.3 |

7.7 |

| 50 |

175.5 |

3.57 |

69.0 |

7.8 |

| 51 |

160 |

2.96 |

62.9 |

6.5 |

| 52 |

168.5 |

3.2 |

66.3 |

7.0 |

| 53 |

168.5 |

3.52 |

66.3 |

7.7 |

| 54 |

159.5 |

3.32 |

62.7 |

7.3 |

| 55 |

151 |

2.96 |

59.4 |

6.5 |

| 56 |

149 |

2.89 |

58.6 |

6.3 |

| 57 |

150.5 |

3.1 |

59.2 |

6.8 |

| 58 |

174.5 |

3.55 |

68.7 |

7.8 |

| 59 |

155.5 |

3.06 |

61.2 |

6.7 |

| 60 |

155.5 |

3.21 |

61.2 |

7.0 |

| 61 |

161 |

3.07 |

63.3 |

6.7 |

| 62 |

157 |

3.18 |

61.8 |

7.0 |

| 63 |

144.5 |

3.18 |

56.8 |

7.0 |

| 64 |

159.5 |

3.14 |

62.7 |

6.9 |

| 65 |

177 |

2.7 |

69.6 |

5.9 |

| 66 |

185 |

1.72 |

72.8 |

3.8 |

| 67 |

160 |

1.71 |

62.9 |

3.7 |

| 68 |

159 |

1.52 |

62.5 |

3.3 |

| 69 |

158.5 |

1.56 |

62.4 |

3.4 |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| Stats |

Length

in cm |

Weight

in kg |

Length

in inches |

Weight

in pounds |

| Min. |

144.5 |

1.52 |

56.9 |

3.3 |

| Max. |

199 |

5.92 |

78.3 |

13.0 |

| Average |

170.6 |

3.5 |

67.1 |

7.8 |

| Mode |

169 |

3.51 |

66.5 |

7.7 |

|

|

Conclusion

A

sword's weight cannot be judged just from its size or blade width.

Hilt style and blade cross-section are determining factors in a weapon's

mass. Just because a blade is thinner does not mean it is necessarily

lighter. For example, an Italian side-sword from circa 1550-1560 of

43.5 inches length weighs in at only 2 pounds 6 ounces, while a typical

rapier that is much more slender bladed from the same era but just

a few inches longer, weighs 2 pounds 9 ounces and still another only

5 inches longer at 3 pounds 3 ounces.From the late 1400s, a large

double-handed Kriegsmesser (or "war knife") of 49.5 inches

length is listed as weighing only 3.8 pounds (see the Metropolitan's

1982, Art of Chivalry, p. 90 & 93-94 for samples). A

sword's weight cannot be judged just from its size or blade width.

Hilt style and blade cross-section are determining factors in a weapon's

mass. Just because a blade is thinner does not mean it is necessarily

lighter. For example, an Italian side-sword from circa 1550-1560 of

43.5 inches length weighs in at only 2 pounds 6 ounces, while a typical

rapier that is much more slender bladed from the same era but just

a few inches longer, weighs 2 pounds 9 ounces and still another only

5 inches longer at 3 pounds 3 ounces.From the late 1400s, a large

double-handed Kriegsmesser (or "war knife") of 49.5 inches

length is listed as weighing only 3.8 pounds (see the Metropolitan's

1982, Art of Chivalry, p. 90 & 93-94 for samples).

One historian states, "The true two-handers really did require two

hands, though their overall weight averaged only about 8 to 10 pounds.

With blades of up to 45 inches or more, the hilts had to be at least

9 inches to counterbalance such a long blade. The crossguard's length

also helped in distributing weight." (William J. McPeak. "For a Swordsmen

with Muscle as Well as Skill, Two Hands Could be Better Than One".

Military History, Oct 2001, Vol. 18. Issue 4, p 24).

Despite

the facts above, many are convinced today that these large swords

simply are, or even have to be, exceptionally heavy. The view is not

one limited to modern times. For example, Thomas Page's otherwise

unremarkable 1746 military fencing booklet, The Use of the Broad

Sword, exclaimed nonsense about earlier swords that became largely

accepted as fact in the 19th (and 20th) century. Revealing something

of how much things in that period had changed from earlier skills

and knowledge of martial fencing, declared how their: "Form was rude,

and their use without Method. They were the Instruments of Strength,

not the Weapons of Art. The Sword was enormous length and breadth,

heavy and unwieldy, design'd only for right down chopping by the Force

of a strong Arm." (Page, p. A3). Page's views were not uncommon among

fencers then used to featherweight smallswords and the occasional

saber and short cutlass. Despite

the facts above, many are convinced today that these large swords

simply are, or even have to be, exceptionally heavy. The view is not

one limited to modern times. For example, Thomas Page's otherwise

unremarkable 1746 military fencing booklet, The Use of the Broad

Sword, exclaimed nonsense about earlier swords that became largely

accepted as fact in the 19th (and 20th) century. Revealing something

of how much things in that period had changed from earlier skills

and knowledge of martial fencing, declared how their: "Form was rude,

and their use without Method. They were the Instruments of Strength,

not the Weapons of Art. The Sword was enormous length and breadth,

heavy and unwieldy, design'd only for right down chopping by the Force

of a strong Arm." (Page, p. A3). Page's views were not uncommon among

fencers then used to featherweight smallswords and the occasional

saber and short cutlass.

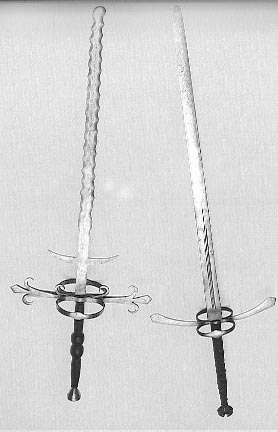

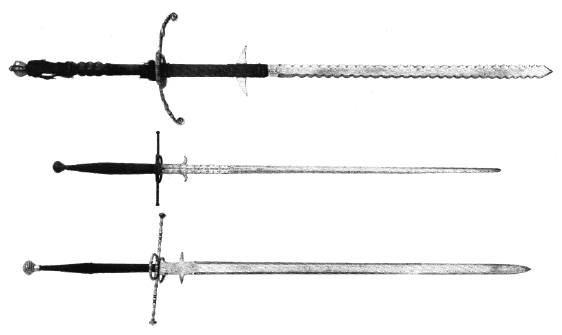

European

sword making technologies throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance

were quite capable of producing high-quality, lightweight, and flexible

steel blades for cutting swords that could hold keen edges. These

weapons were not intended to defeat heavy plate armor with powerful

cuts but did evolve from those longswords that were developed for

use against armors by thrusting rather than cutting. Handling

real specimens of some of these enormous but beautiful weapons [such

as seen in the three images to the right] is enlightening, for their

size betrays their exceptional balance. It very quickly becomes clear

they were intended for large fighting men to deliver not only powerful

slashing blows but great stabbing attacks as well as pole-weapon-like

techniques. Large as they were, they were not ridiculously heavy. European

sword making technologies throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance

were quite capable of producing high-quality, lightweight, and flexible

steel blades for cutting swords that could hold keen edges. These

weapons were not intended to defeat heavy plate armor with powerful

cuts but did evolve from those longswords that were developed for

use against armors by thrusting rather than cutting. Handling

real specimens of some of these enormous but beautiful weapons [such

as seen in the three images to the right] is enlightening, for their

size betrays their exceptional balance. It very quickly becomes clear

they were intended for large fighting men to deliver not only powerful

slashing blows but great stabbing attacks as well as pole-weapon-like

techniques. Large as they were, they were not ridiculously heavy.

For

more than a century two-handed greatswords were used less for fighting

against armors and more for open battlefield where pike and halberd

formations were combined with firearms. Accordingly, just as with

its shorter single-hand cousins, the late 15th and early 16th century

two-handed greatsword was not a crude excessively heavy bludgeoning

weapon but a fairly agile and balanced weapon designed for close-combat

in war and occasional duel. For

more than a century two-handed greatswords were used less for fighting

against armors and more for open battlefield where pike and halberd

formations were combined with firearms. Accordingly, just as with

its shorter single-hand cousins, the late 15th and early 16th century

two-handed greatsword was not a crude excessively heavy bludgeoning

weapon but a fairly agile and balanced weapon designed for close-combat

in war and occasional duel.

Appreciation to Grzegorz Zabinski for sharing

additional data and Stewart Feil for editing assistance. All

quotes here are provided by permission of the sources.

See also: What

Did Medieval Swords Weigh?

October 2004

|