|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

ARMA Editorial - Sept. 2010 The Intangible Cultural

Heritage of Martial Traditions The Intangible Cultural

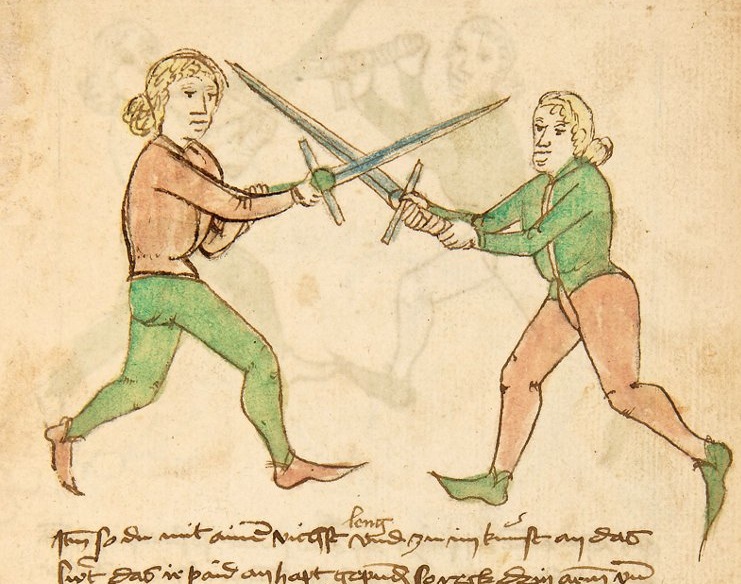

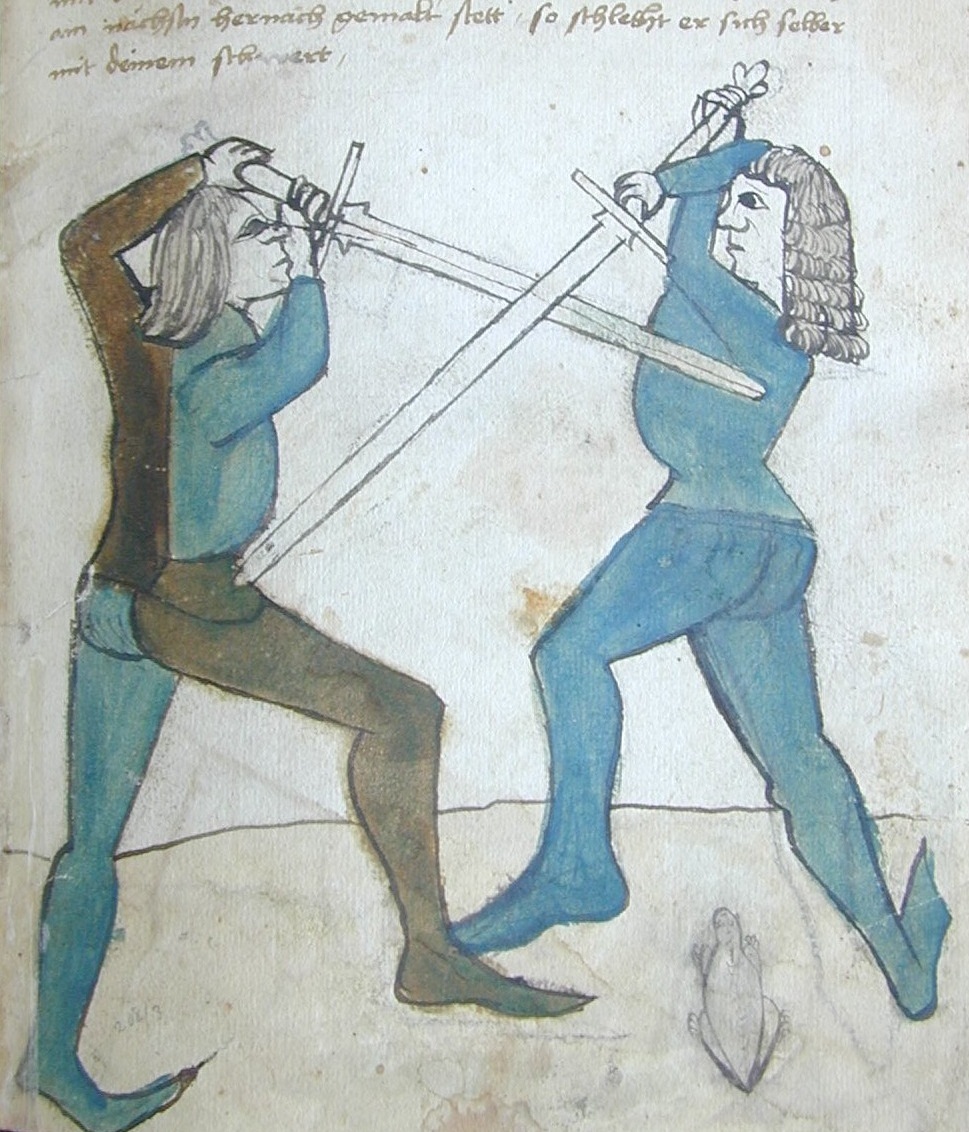

Heritage of Martial TraditionsBy John Clements Something interesting occurs to me when I consider the larger picture of reclaiming and recovering our Renaissance martial heritage. The martial arts of Renaissance Europe (which we might conveniently abbreviate as “MARE”) are a subject that has to be reconstituted and restored by holistic study of its surviving teachings. Experts from the 14th to 17th centuries left behind for us unmatched historical documentation for their personal combat methods covering the reality of self-defense in battle, duel, and street encounter. This vast technical literature represents time-capsules of authenticity for us, in that they are undiluted and unpolluted by the civilianizing de-martialization that later occurs as generation after generation no longer has need to practice such integrated combat skills. A heritage is something that’s inherited. That is, it is knowledge preserved from the past for the future. Our source material on MARE is undeniably something that was very much retained in written and illustrated form. This instructional literature, surviving among voluminous treatises and collected works, is therefore something that as a community of students we have very much inherited. Despite being extinct and little known, this material is unequaled in its technical and iconographic detail. It arguably represents the most well documented martial arts teachings in history—even more so than any extant Asian equivalent. In this regard, it is certainly a powerful (albeit broken) “tradition”—far more so than something recently invented out of a known Asian-style restructured and reformatted for para-military or competitive application. While it’s recorded teachings were not saved as any pedagogic tradition (certainly not among modern or classical fencing instructors who focused only on gentlemanly dueling and sport), its study reveals an indigenous science of defense—self-defense systems and fighting methodologies based on established principles of close combat. The means by which these skills were once acquired may be what is now missing to us, but the methods themselves were preserved. As we uncover, recover, and reproduce these forgotten combative disciplines, we are not reinventing today, but rather, preserving them once again.  While

we may never know with full confidence how our craft was

authentically

performed or practiced by the historical Masters of

Defence, our source

teachings don’t suffer from being commercialized,

sportified,

idealized, or mythologized. Thus, we have come to

know -- with

great depth -- their theories, principles, concepts,

techniques, and

philosophy of self-defense. To be able at this point to

say these were

highly sophisticated and systematic close-combat methods

almost sounds

like a cliché, since virtually every fighting

discipline on the planet regularly assumes such a label

now. While

we may never know with full confidence how our craft was

authentically

performed or practiced by the historical Masters of

Defence, our source

teachings don’t suffer from being commercialized,

sportified,

idealized, or mythologized. Thus, we have come to

know -- with

great depth -- their theories, principles, concepts,

techniques, and

philosophy of self-defense. To be able at this point to

say these were

highly sophisticated and systematic close-combat methods

almost sounds

like a cliché, since virtually every fighting

discipline on the planet regularly assumes such a label

now.  It’s

no secret to observe that not all martial art traditions

can be equally

substantiated. But in past decades I witnessed

first hand

attempts to practice Medieval and Renaissance fencing

skills that were

little more than regurgitated stage combat

cliché’s mixed with sport

fencing and Asian swordplay. So, having rediscovered so

much genuine material perhaps I find myself more

sensitive

to assertions of "historical" fighting styles that seem

to me less

representative of a martial cultural than an eclectic

mix of exposure

to popular contemporary styles. If I compare the depth

of our authentic instructional material to some

“vernacular”

fighting styles that were ostensibly "preserved" --

despite their

having long ago lost the necessity of being utilized in

lethal

situations or taught with formalized curricula -- the

result leaves me

feeling personally quite confident about the

re-development of our

craft. My own skill set convinces me the rest of the

way. It’s

no secret to observe that not all martial art traditions

can be equally

substantiated. But in past decades I witnessed

first hand

attempts to practice Medieval and Renaissance fencing

skills that were

little more than regurgitated stage combat

cliché’s mixed with sport

fencing and Asian swordplay. So, having rediscovered so

much genuine material perhaps I find myself more

sensitive

to assertions of "historical" fighting styles that seem

to me less

representative of a martial cultural than an eclectic

mix of exposure

to popular contemporary styles. If I compare the depth

of our authentic instructional material to some

“vernacular”

fighting styles that were ostensibly "preserved" --

despite their

having long ago lost the necessity of being utilized in

lethal

situations or taught with formalized curricula -- the

result leaves me

feeling personally quite confident about the

re-development of our

craft. My own skill set convinces me the rest of the

way.  When

you think about it, while

a traditional established or extant martial art may

proclaim

that what they do is something extant or "living" --

having been

"passed down" or transmitted person to person in an

ostensibly unbroken

process -- that in no way insures it has been immune to

change or

subject to inaccuracies over time. Like the old

children’s game

of "telephone," both external forces and internal

subjectivity can have

influence on the supposed immutability of any

“unchanging” tradition. When

you think about it, while

a traditional established or extant martial art may

proclaim

that what they do is something extant or "living" --

having been

"passed down" or transmitted person to person in an

ostensibly unbroken

process -- that in no way insures it has been immune to

change or

subject to inaccuracies over time. Like the old

children’s game

of "telephone," both external forces and internal

subjectivity can have

influence on the supposed immutability of any

“unchanging” tradition.  By

contrast, our lost martial “tradition” is being revived

and

reconstituted from the very technical instructions of

the actual

fighting masters of the age as presented in the

unrivaled collective

material of their own words and images. We have at our

disposal

documented sources covering a host of authentic

teachings from over

four centuries of sophisticated combatives. What we

study is also a

largely repertoire of specific techniques from specific

sources, along

with underlying principles and concepts formulated into

systems or

methods -- what we might, dare I say, call styles. We

also understand

the cultural and social context in which this Noble

Science was

practiced and employed, with its associated chivalric

and humanist

values. All of this means, in my opinion, our

craft is arguably

more documented and verifiable in its authenticity

because it has been

subject to far less distortion and contamination over

time. By

contrast, our lost martial “tradition” is being revived

and

reconstituted from the very technical instructions of

the actual

fighting masters of the age as presented in the

unrivaled collective

material of their own words and images. We have at our

disposal

documented sources covering a host of authentic

teachings from over

four centuries of sophisticated combatives. What we

study is also a

largely repertoire of specific techniques from specific

sources, along

with underlying principles and concepts formulated into

systems or

methods -- what we might, dare I say, call styles. We

also understand

the cultural and social context in which this Noble

Science was

practiced and employed, with its associated chivalric

and humanist

values. All of this means, in my opinion, our

craft is arguably

more documented and verifiable in its authenticity

because it has been

subject to far less distortion and contamination over

time.  Yes,

we do have a continual task of research and ongoing

analysis

facing us -- even as we gain increasing confidence in

understanding the

totality of their teachings -- but such interpretation

and subsequent

experimental application is a necessary aspect of its

revival. After

all, the real richness of any martial tradition is in its

physical

movement and lessons on applying core principles, the things

learned in

person from those who know. The work involved

certainly produces a sense of investigation and

exploration that makes our

discipline dynamic and once again living. They are

not fixed and

"completed" arts that go are unquestioned and unexamined

as to their

efficacy and viability by virtue of an authority

claiming ownership of

a pedagogical lineage. The real difficulty for us

in seeking

accurate approximation of extinct fighting methods today

is far less in

mis-interpretation or avoiding orthodoxy. The danger we

face instead

lies in avoiding the role-playing reenactment and

costumed escapism

mentality that still plagues so much interest in

historical combat and

which, at the least, invariably leads to sportification

and the underperformance of mediocrity. Yes,

we do have a continual task of research and ongoing

analysis

facing us -- even as we gain increasing confidence in

understanding the

totality of their teachings -- but such interpretation

and subsequent

experimental application is a necessary aspect of its

revival. After

all, the real richness of any martial tradition is in its

physical

movement and lessons on applying core principles, the things

learned in

person from those who know. The work involved

certainly produces a sense of investigation and

exploration that makes our

discipline dynamic and once again living. They are

not fixed and

"completed" arts that go are unquestioned and unexamined

as to their

efficacy and viability by virtue of an authority

claiming ownership of

a pedagogical lineage. The real difficulty for us

in seeking

accurate approximation of extinct fighting methods today

is far less in

mis-interpretation or avoiding orthodoxy. The danger we

face instead

lies in avoiding the role-playing reenactment and

costumed escapism

mentality that still plagues so much interest in

historical combat and

which, at the least, invariably leads to sportification

and the underperformance of mediocrity. So,

when I hear about, say, traditional Eskimo martial

arts, it’s

proponents may contend some justifiable restoration from

a vernacular

source to then set up a modern program with its own

unique name.

Maybe it’s genuine; maybe not. I can't help but

think that

nearly everyone in every ethnic group, geographic

region, and society

today has seen enough martial arts books and movies that

they can adapt

some techniques, invent some routines, put on some

indigenous garb, and

use some arcane terminology until -- poof! – they’ve

authoritatively

reconstituted an "art" and a "tradition" (one that

"somebody’s family in

the old country kept secret until now"). But, a

mere 50 or 100

years ago (coincidentally before pop culture exported

Bruce Lee and

related material to the world) no one documented it as

having sustained and preserved a fighting art

-- if it ever existed as a methodology. Go figure.

Meanwhile, I'm waiting for sophisticated

"Cro-Magnon martial arts" to soon be

"re-discovered." So,

when I hear about, say, traditional Eskimo martial

arts, it’s

proponents may contend some justifiable restoration from

a vernacular

source to then set up a modern program with its own

unique name.

Maybe it’s genuine; maybe not. I can't help but

think that

nearly everyone in every ethnic group, geographic

region, and society

today has seen enough martial arts books and movies that

they can adapt

some techniques, invent some routines, put on some

indigenous garb, and

use some arcane terminology until -- poof! – they’ve

authoritatively

reconstituted an "art" and a "tradition" (one that

"somebody’s family in

the old country kept secret until now"). But, a

mere 50 or 100

years ago (coincidentally before pop culture exported

Bruce Lee and

related material to the world) no one documented it as

having sustained and preserved a fighting art

-- if it ever existed as a methodology. Go figure.

Meanwhile, I'm waiting for sophisticated

"Cro-Magnon martial arts" to soon be

"re-discovered." |

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||