Martial

Arts Heritage is as Global as it is Personal Martial

Arts Heritage is as Global as it is Personal

By John Clements

ARMA Director

This is the most difficult piece I've ever written

about the subject of martial arts. Probably no matter what I express

here it's going to be misread by someone somewhere. But no less, here

it goes: Every January, I receive a wave of New Year applications

for ARMA memberships and inquiries for introductory sessions at my

Iron Door School of Arms. Invariably, there's always at least one

person who feels the need to express in the section on why they are

interested that it's because they want to pursue "white martial arts".

...Ugggh. Needless to say, I delete such applications and emails.

Now, one could certainly make a case that it's simply

poor wording choice on the part of the individual and what they really

meant is that they are interested in the authentic Western fighting

methods of their own European ancestors. Fair enough. It's a reasonable

interest for anyone to want to know about a past they feel some connection

toward. But, the phrase "white martial arts" is loaded with certain

implicit insinuations and subtexts I'd just prefer to avoid. My first

instinct is to respond, "Riiiggghttt... I'm not gonna touch that."

As with any other historical styles, these are fighting

arts self-evidently from a specific geographic, cultural, and temporal

region. It’s certainly “occidental.” Why assign any other label? Personally,

I'm not going there. I see it as unnecessarily divisive. It's neither

welcoming nor inclusive and I refuse to dignify it (I even had a falling

out with a close colleague over just such an attitude). Similarly,

those individuals whose inquiries express a certain resentment or

grievance towards the popularity of more established and widely known

martial arts traditions of other cultures strike me as characters

with whom I wouldn't get along or care to be associated. To me, it's

as ignorant as insulting different cuisines or different music. And

I write this as someone who when a teen on several occasions was told

to my face with veiled derision how "you in the West had no martial

arts."

I

have heard the phrase "martial arts of the orient" (as opposed to

Occident) but I never heard of anything being referred to as "yellow

martial arts" or "brown martial arts" or, for that matter, by any

other color or racial grouping, nor do I wish to see it start. Yes,

most fighting arts are designated as being from particular nations,

lands, or regions that historically were both ethnically and culturally

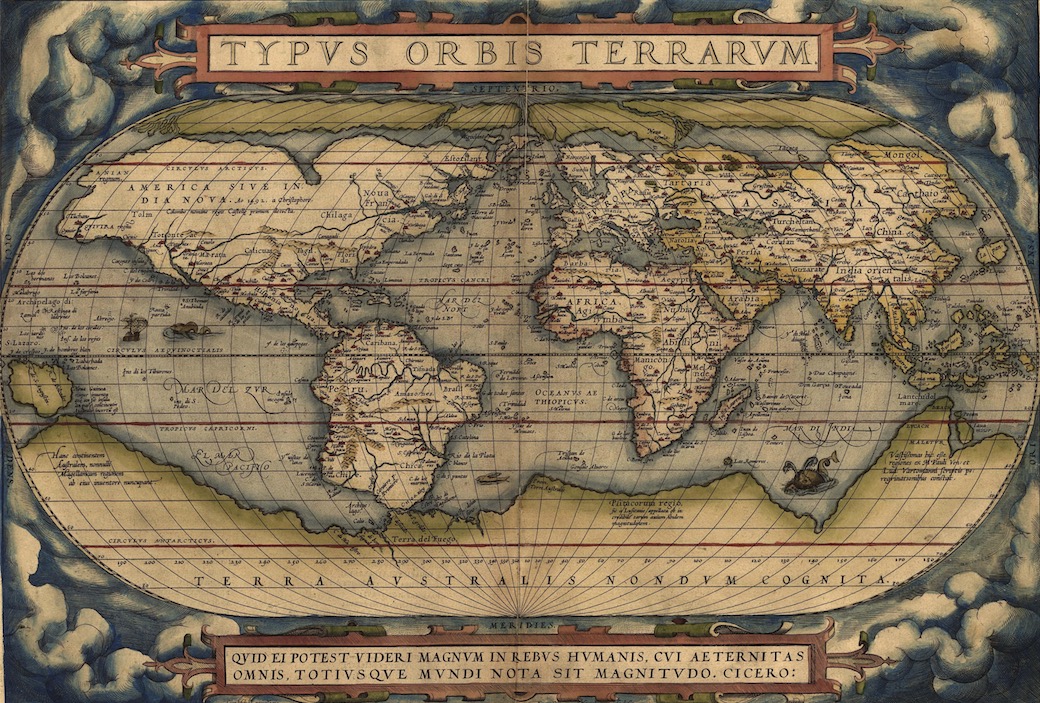

homogeneous. But again, so what? I perfectly understand the excitement

someone feels when they learn that their ancestors actually documented

sophisticated martial art systems that can be practiced once again.

I entirely relate to the sense of pride in realizing that martial

arts weren't something limited to a few places on one part of the

planet. But, I also equally understand the sense of wonder and curiosity

felt by anyone from anywhere wanting to explore and gain prowess in

"exotic foreign" teachings out of a warrior past. I have tens of students

around the world, from Korea to Israel to Russia, and it's no different

for them to learn 14th century Kunst des Fechten or La Destreza

of the Spanish court than it is for my Lebanese neighbor to be interested

in kenjutsu or kung fu. (Though to be honest, I do tend to roll my

eyes at modern Westerners so infatuated with being samurai or ninja

that it becomes their entire self-identity.) I

have heard the phrase "martial arts of the orient" (as opposed to

Occident) but I never heard of anything being referred to as "yellow

martial arts" or "brown martial arts" or, for that matter, by any

other color or racial grouping, nor do I wish to see it start. Yes,

most fighting arts are designated as being from particular nations,

lands, or regions that historically were both ethnically and culturally

homogeneous. But again, so what? I perfectly understand the excitement

someone feels when they learn that their ancestors actually documented

sophisticated martial art systems that can be practiced once again.

I entirely relate to the sense of pride in realizing that martial

arts weren't something limited to a few places on one part of the

planet. But, I also equally understand the sense of wonder and curiosity

felt by anyone from anywhere wanting to explore and gain prowess in

"exotic foreign" teachings out of a warrior past. I have tens of students

around the world, from Korea to Israel to Russia, and it's no different

for them to learn 14th century Kunst des Fechten or La Destreza

of the Spanish court than it is for my Lebanese neighbor to be interested

in kenjutsu or kung fu. (Though to be honest, I do tend to roll my

eyes at modern Westerners so infatuated with being samurai or ninja

that it becomes their entire self-identity.)

I

suppose that as a modern American, whose ancestry is Italian, Sicilian,

German, and English, I don't readily identify with any one ethnic

or national affiliation when it comes to what Renaissance martial

art sources I enjoy studying. Yes, my ancestry is entirely European,

but so what? My style of study is the systematic fighting arts of

Western civilization during a specific time known as the Medieval

and Renaissance eras. It is the "noble art and science of defence"

--and among the most sophisticated and effective ever devised. They

are unequivocally the martial arts of Western civilization

(just as its Asian counterparts are those of Eastern civilizations).

Not only that, but I do not know of a single historical source of

Renaissance martial arts teachings that could not essentially be described

as being "Latin," or connected directly to Judaeo-Christian ideas

of chivalry (itself undeniably connected to per-Christian Germanic,

Nordic, and Celtic concepts). But even then, it owes a tremendous

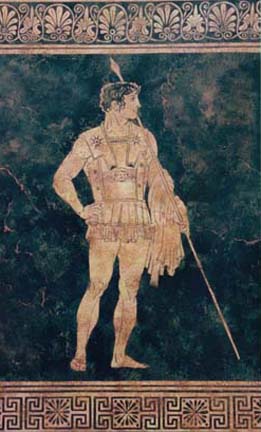

debt to the Greek within the "Greco-Roman" and we cannot for

an instant ignore Slavic martial contributions, either. I

suppose that as a modern American, whose ancestry is Italian, Sicilian,

German, and English, I don't readily identify with any one ethnic

or national affiliation when it comes to what Renaissance martial

art sources I enjoy studying. Yes, my ancestry is entirely European,

but so what? My style of study is the systematic fighting arts of

Western civilization during a specific time known as the Medieval

and Renaissance eras. It is the "noble art and science of defence"

--and among the most sophisticated and effective ever devised. They

are unequivocally the martial arts of Western civilization

(just as its Asian counterparts are those of Eastern civilizations).

Not only that, but I do not know of a single historical source of

Renaissance martial arts teachings that could not essentially be described

as being "Latin," or connected directly to Judaeo-Christian ideas

of chivalry (itself undeniably connected to per-Christian Germanic,

Nordic, and Celtic concepts). But even then, it owes a tremendous

debt to the Greek within the "Greco-Roman" and we cannot for

an instant ignore Slavic martial contributions, either.

But

what of that loaded phrase "white martial arts"? Why should I find

it troublesome? I'll leave it to the reader to explore that on their

own, but I will say with regard to the martial arts of Renaissance

Europe, we certainly are talking about a body of literature reflecting

fighting methods and self-defense systems produced by people who were

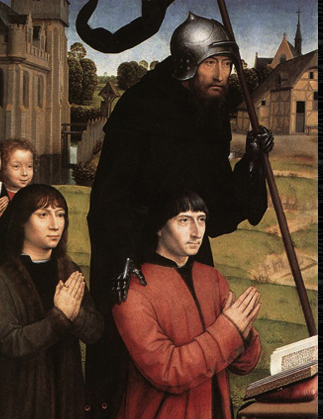

undeniably Caucasian, sure. But so what? Should anyone today really

care one way or the other? (What exactly, I wonder, would the applicants

I reject make of the fact that there are black Africans prominently

featured training in our 15th and 16th century sources? or the frequency

of brown-skinned icons of Saint Maurice in knightly armor? or the

contribution made by Jews?) It's funny, but when I was a child and

would see martial arts films or historical epics I had no problem

either identifying with or not identifying with the warriors and duelists

on screen, because as a child I was more or less oblivious to it.

Ethnic identity, racial affiliation, et cetera, was irrelevant to

the fact that I was seeing heroic fighting men overcoming injustice

with skill and courage. I think I never outgrew that even as I came

to discover and promote the very subject I do. But

what of that loaded phrase "white martial arts"? Why should I find

it troublesome? I'll leave it to the reader to explore that on their

own, but I will say with regard to the martial arts of Renaissance

Europe, we certainly are talking about a body of literature reflecting

fighting methods and self-defense systems produced by people who were

undeniably Caucasian, sure. But so what? Should anyone today really

care one way or the other? (What exactly, I wonder, would the applicants

I reject make of the fact that there are black Africans prominently

featured training in our 15th and 16th century sources? or the frequency

of brown-skinned icons of Saint Maurice in knightly armor? or the

contribution made by Jews?) It's funny, but when I was a child and

would see martial arts films or historical epics I had no problem

either identifying with or not identifying with the warriors and duelists

on screen, because as a child I was more or less oblivious to it.

Ethnic identity, racial affiliation, et cetera, was irrelevant to

the fact that I was seeing heroic fighting men overcoming injustice

with skill and courage. I think I never outgrew that even as I came

to discover and promote the very subject I do.

Amusingly,

ascribing a racial component to our craft is as irrelevant as it is

incongruous. One does not have to go back many centuries or generations

to find extreme prejudice and hatred between the very groups that

make up what the minuscule number of applicants whom I reject would

like to call "white martial arts." There was enmity between Celts

and Latins, Scots and English, English and Irish, between almost anyone

within the Italian states, and among nearly endless other peoples

from Spain to the Baltic and Belgium to the Balkans. I'm quite sure

a 16th century Venetian, for instance, would have plenty of rude and

crude insults to give any number of Lombards, Flems, Burgundians,

Basques, Bohemians, Britons and what have you. Plus, nearly all of

them at one time or another were going to war with Turks and Saracens

(who were busy fighting themselves). None of which matters the slightest

today to our work in recovering and reviving forgotten martial skills.

Incidentally, the Latin word for greater groups of humans such as

tribes, nations, or what we call peoples, was gentes. It's

worth nothing that they had an understanding of these things and yet

did not obsess over them. Amusingly,

ascribing a racial component to our craft is as irrelevant as it is

incongruous. One does not have to go back many centuries or generations

to find extreme prejudice and hatred between the very groups that

make up what the minuscule number of applicants whom I reject would

like to call "white martial arts." There was enmity between Celts

and Latins, Scots and English, English and Irish, between almost anyone

within the Italian states, and among nearly endless other peoples

from Spain to the Baltic and Belgium to the Balkans. I'm quite sure

a 16th century Venetian, for instance, would have plenty of rude and

crude insults to give any number of Lombards, Flems, Burgundians,

Basques, Bohemians, Britons and what have you. Plus, nearly all of

them at one time or another were going to war with Turks and Saracens

(who were busy fighting themselves). None of which matters the slightest

today to our work in recovering and reviving forgotten martial skills.

Incidentally, the Latin word for greater groups of humans such as

tribes, nations, or what we call peoples, was gentes. It's

worth nothing that they had an understanding of these things and yet

did not obsess over them.

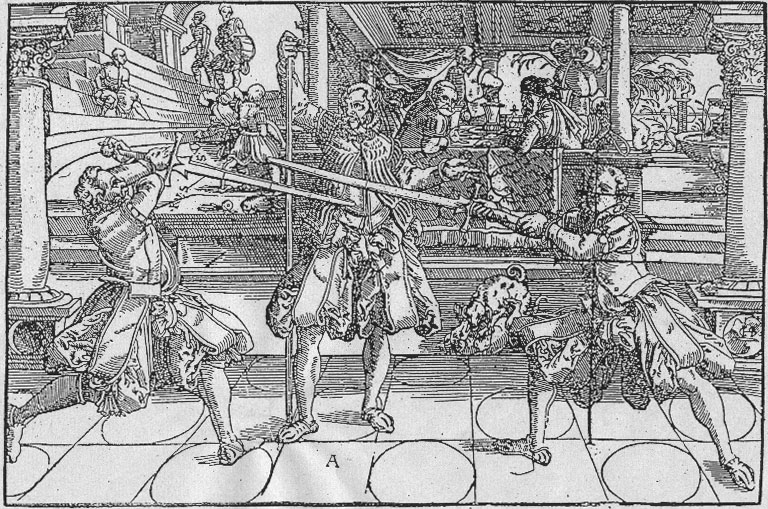

In

an age when they had Scottish masters presenting French fencing, or

Florentine masters teaching in Scandinavia, Flemish masters teaching

Spanish fencing at the Court of France, and Spanish masters teaching

in Italy, not to mention knights from most anywhere traveling across

the continent to engage in tournament contests, labeling things now

with modern nationalistic identities is all but meaningless. Arguably,

a case can be made that it's actually difficult to refer to "Italian"

martial arts excepting in regard to those authors originating among

the Italian city states. The same can be said for those sources originating

among Germanic states or kingdoms, or rather, those that were under

Germanic political control at the time their teachings were recorded. In

an age when they had Scottish masters presenting French fencing, or

Florentine masters teaching in Scandinavia, Flemish masters teaching

Spanish fencing at the Court of France, and Spanish masters teaching

in Italy, not to mention knights from most anywhere traveling across

the continent to engage in tournament contests, labeling things now

with modern nationalistic identities is all but meaningless. Arguably,

a case can be made that it's actually difficult to refer to "Italian"

martial arts excepting in regard to those authors originating among

the Italian city states. The same can be said for those sources originating

among Germanic states or kingdoms, or rather, those that were under

Germanic political control at the time their teachings were recorded.

So

again, as a modern American, from a country that did not have a 'Middle

Ages" or experience "the Renaissance," I'm fascinated with European

history from those times. (And I don't really relate to my European

colleagues who seem insistent upon limiting themselves to focus on

source works produced within their own country —what they see as their

"ancestors.") Though, I will confess that more than once I have put

it to some American obsessed with being a modern Western samurai,

"So... you really revere this discipline from a social and religious

structure that essentially said, 'honor your ancestors' ...hmm...

wonder what your instructor thinks of your doing that?" The

point being, no culture is immune from its particular history of prejudices

and bigotry and we shouldn't pretend otherwise. Besides, the martial

arts of Asia are much more than just those of the "Orient" but includes

ones from the larger Pacific rim, the Indian subcontinent, Persia,

and elsewhere. So

again, as a modern American, from a country that did not have a 'Middle

Ages" or experience "the Renaissance," I'm fascinated with European

history from those times. (And I don't really relate to my European

colleagues who seem insistent upon limiting themselves to focus on

source works produced within their own country —what they see as their

"ancestors.") Though, I will confess that more than once I have put

it to some American obsessed with being a modern Western samurai,

"So... you really revere this discipline from a social and religious

structure that essentially said, 'honor your ancestors' ...hmm...

wonder what your instructor thinks of your doing that?" The

point being, no culture is immune from its particular history of prejudices

and bigotry and we shouldn't pretend otherwise. Besides, the martial

arts of Asia are much more than just those of the "Orient" but includes

ones from the larger Pacific rim, the Indian subcontinent, Persia,

and elsewhere.

Now,

it's absolutely understandable if someone says that because of their

family background, or even lineage, they feel a direct cultural connection

for the personal combat disciplines of their own nation or distant

relations. Hence, someone in Japan would naturally be more inclined

to study traditional Japanese styles, or someone in the Philippines

would be regularly exposed to Filipino arts, and so on. But here's

where I will make an observation: you don't have to be Russian to

dance well in a Tchaikovsky ballet, or be English to perform admirably

in a production of Shakespeare's Hamlet, or be Italian to make great

pizza. You don't have to be a native of India to enjoy an excellent

curry, be Swiss to build a fine watch, or descended from samurai to

practice jujitsu superbly. You might be able to better read directions

for performing a samba if you know Portuguese like your grandparents,

but that doesn't mean you can dance it better. None of this kind of

information is held genetically, none of this kind of knowledge and

wisdom is dependent upon our family tree and indeed, none of these

activities favors a particular genotype. Further, most often little

to none of the skills and talents involved is cultural, let alone

any longer exclusive to one community, clan, neighborhood, household,

or whatever. While there is no disputing that the origin of certain

fighting styles could favor indigenous physiques and temperaments,

benefit from its original milieu, or be aided by the footwear and

garments once worn by those inhabitants who developed it, this is

much less true today. Bottom line is, neither race nor national identity

plays a part in how we learn and what we achieve in any combat discipline.

What matters is individual effort and attitude. Now,

it's absolutely understandable if someone says that because of their

family background, or even lineage, they feel a direct cultural connection

for the personal combat disciplines of their own nation or distant

relations. Hence, someone in Japan would naturally be more inclined

to study traditional Japanese styles, or someone in the Philippines

would be regularly exposed to Filipino arts, and so on. But here's

where I will make an observation: you don't have to be Russian to

dance well in a Tchaikovsky ballet, or be English to perform admirably

in a production of Shakespeare's Hamlet, or be Italian to make great

pizza. You don't have to be a native of India to enjoy an excellent

curry, be Swiss to build a fine watch, or descended from samurai to

practice jujitsu superbly. You might be able to better read directions

for performing a samba if you know Portuguese like your grandparents,

but that doesn't mean you can dance it better. None of this kind of

information is held genetically, none of this kind of knowledge and

wisdom is dependent upon our family tree and indeed, none of these

activities favors a particular genotype. Further, most often little

to none of the skills and talents involved is cultural, let alone

any longer exclusive to one community, clan, neighborhood, household,

or whatever. While there is no disputing that the origin of certain

fighting styles could favor indigenous physiques and temperaments,

benefit from its original milieu, or be aided by the footwear and

garments once worn by those inhabitants who developed it, this is

much less true today. Bottom line is, neither race nor national identity

plays a part in how we learn and what we achieve in any combat discipline.

What matters is individual effort and attitude.

In many cultures, the primal idea of a connection

between ethnicity and virtue was expressed by the term "blood" —as

in, bad blood, impure blood, mixed blood, half blood, family blood,

etc. Today, this is anachronistic, to put it mildly. We've replaced

it with debates over nature and nurture. While it's perfectly true

to point out that a particular fighting style may contain techniques

or elements better fitting the overall physical build of its native

fighting population, the diversity of human physical form is such

that one can find matching body types among different peoples around

the globe. That some methods of fighting or some arms and armor developed

more in isolation than did others, also renders any indigenous advantage

assertion irrelevant today. Not to mention that our global culture,

combined with the ease of international travel, allows people to readily

share in even the most obscure and secretive fighting methods from

antiquity with ease.

This

is why I love the Master Joachim Meyer's statement in 1570 on the

necessity of knowing how every man fights, because even though we

all move differently and all think differently, everyone must attest

that all fighting comes from a common basis. So true. Yet, I will

confess that I get a tremendous enjoyment out of crushing people's

misconceptions about Medieval and Renaissance combat skills. I immensely

enjoy educating people out of their ignorance about the craft that

is my life's work, especially when they have thought themselves wise

about all matters "martial art." Too long the definition of the term

has been entirely synonymous with meaning popular Asian fighting styles,

and I am more than happy to have played a large part in changing that.

But when I do inform people, I do it out of the love of history and

heritage I hold as a scholar and practitioner. This

is why I love the Master Joachim Meyer's statement in 1570 on the

necessity of knowing how every man fights, because even though we

all move differently and all think differently, everyone must attest

that all fighting comes from a common basis. So true. Yet, I will

confess that I get a tremendous enjoyment out of crushing people's

misconceptions about Medieval and Renaissance combat skills. I immensely

enjoy educating people out of their ignorance about the craft that

is my life's work, especially when they have thought themselves wise

about all matters "martial art." Too long the definition of the term

has been entirely synonymous with meaning popular Asian fighting styles,

and I am more than happy to have played a large part in changing that.

But when I do inform people, I do it out of the love of history and

heritage I hold as a scholar and practitioner.

I will share an anecdote: I once had a conversation

over breakfast with a respected modern Japanese samurai. His being

both a well-traveled veteran martial artist of a noted tradition as

well as a senior citizen, I was curious to put a question to him.

I premised my question with the statement that: given how —in terms

of arms and armor and military methods— the samurai of the year 1250

were not identical to the samurai of the year 1450, who were certainly

not the same as the samurai of 1650, let alone those of 1850 or 2015,

what exactly then, I asked, was the 'fighting tradition' he was practicing

and preserving? The response I received through his interpreter was

remarkably reassuring. He told me that it was "none of them and all

of them." His answer was exactly the response I had wanted but hardly

expected to hear, for I have long held the very same view towards

the pursuit of my Art. I also believe in the modern world this is

true for study of all of the world's martial arts "traditions."

To use an analogy: My wife is proud to share her grandmother's

delicious recipe for Cajun chicken stew knowing full well that those

who attempt it will never match the delightful subtlety of flavors

that she grew up with. This doesn't stop her from offering others

the opportunity to at least attempt to enjoy some version reminiscent

of what she so fondly remembers from her youth. That with every occasion

she makes the dish, she herself knows that although her own version

is not exactly identical, it is less important than using the same

ingredients and following the right steps to produce and share something

both comforting and delicious. Traditional martial arts study is much

the same. We are not those who once developed and employed these methods

out of necessity. In most cases we are far removed from them and the

environments in which they existed. Like the samurai master above,

we are all modernists even as we try to hold connection with the past;

whether or not it is our direct ancestry isn't the point.

If

we refer to German martial arts or English martial arts, or to Swiss

or Spanish, to Norse or Hungarian, there's no issue involved any more

than there is to point out that Japanese martial arts were conceived

and practiced by natives of Japan. It's no more relevant than to note

that Thai food was originally created and eaten by Thais or French

cuisine by the French. Were there times when particular Asian martial

arts traditions were not taught to "outsiders" from other lands? Absolutely.

There hasn't been a culture on Earth that hasn't been guilty of its

own form of ethnocentrism at one time or another. But I don't see

anybody holding a grudge about it. As Bruce Lee himself showed, if

you value a tradition or part of a heritage as worthwhile, then share

it proudly with whoever will learn. Does it matter anymore if you

are "1/16th" this or zero-percent "that"? If

we refer to German martial arts or English martial arts, or to Swiss

or Spanish, to Norse or Hungarian, there's no issue involved any more

than there is to point out that Japanese martial arts were conceived

and practiced by natives of Japan. It's no more relevant than to note

that Thai food was originally created and eaten by Thais or French

cuisine by the French. Were there times when particular Asian martial

arts traditions were not taught to "outsiders" from other lands? Absolutely.

There hasn't been a culture on Earth that hasn't been guilty of its

own form of ethnocentrism at one time or another. But I don't see

anybody holding a grudge about it. As Bruce Lee himself showed, if

you value a tradition or part of a heritage as worthwhile, then share

it proudly with whoever will learn. Does it matter anymore if you

are "1/16th" this or zero-percent "that"?

I've

had some experience in this matter myself in my dealings with the

World Martial Arts Union (WoMAU) as the official representative for

Renaissance martial arts —albeit seated as the delegate from Poland.

How did I as an American citizen with minimal Slavic ancestry come

to represent the country of Poland as being singled out for a diverse

international craft that at the time was pan-European and even now

is still being reconstructed in efforts around the globe? The answer

has to do with the fact that the organization is associated with the

United Nations as an official body of UNESCO and every and all activities

therein are by default seen through the prism of the modern nation

state. Since there are such things as Chinese martial arts, Korean

martial arts, Malaysian martial arts, Indonesian, etc., etc., then

any other fighting style must also be directly associated with a nation

state and its national ethnic body. Obviously this is not the case,

especially with a revived and reconstructed art from centuries past

with zero surviving pedagogic lineage. This assumption wrongly ignores

centuries of demographic, cultural, social, and political change,

not to mention other assorted upheavals and the evolution of military

technology. I've

had some experience in this matter myself in my dealings with the

World Martial Arts Union (WoMAU) as the official representative for

Renaissance martial arts —albeit seated as the delegate from Poland.

How did I as an American citizen with minimal Slavic ancestry come

to represent the country of Poland as being singled out for a diverse

international craft that at the time was pan-European and even now

is still being reconstructed in efforts around the globe? The answer

has to do with the fact that the organization is associated with the

United Nations as an official body of UNESCO and every and all activities

therein are by default seen through the prism of the modern nation

state. Since there are such things as Chinese martial arts, Korean

martial arts, Malaysian martial arts, Indonesian, etc., etc., then

any other fighting style must also be directly associated with a nation

state and its national ethnic body. Obviously this is not the case,

especially with a revived and reconstructed art from centuries past

with zero surviving pedagogic lineage. This assumption wrongly ignores

centuries of demographic, cultural, social, and political change,

not to mention other assorted upheavals and the evolution of military

technology.

The

WoMAU wanted to recognize the legitimacy of Renaissance martial arts

study and include it, but their organizational structure required

every representative to be affiliated with a nation state. Poland

was not yet represented in the Union, and, as it was, I had study

groups in there. That Poland was not a major participant in the historic

changes occurring during the Renaissance era is arguable, but what

is not deniable is its connection with and great contributions to

combat skills from the Middle Ages and continuing well into the 17th

century. (Besides, it's not like the Union could select people from

every EU nation from out dozens of fledgling HEMA groups to represent

every major historical source style now being studied. Better to get

an individual already experienced in teaching internationally who

can represent the subject both physically and scholastically at a

high level while also possessing deep knowledgeable of other martial

traditions.) The

WoMAU wanted to recognize the legitimacy of Renaissance martial arts

study and include it, but their organizational structure required

every representative to be affiliated with a nation state. Poland

was not yet represented in the Union, and, as it was, I had study

groups in there. That Poland was not a major participant in the historic

changes occurring during the Renaissance era is arguable, but what

is not deniable is its connection with and great contributions to

combat skills from the Middle Ages and continuing well into the 17th

century. (Besides, it's not like the Union could select people from

every EU nation from out dozens of fledgling HEMA groups to represent

every major historical source style now being studied. Better to get

an individual already experienced in teaching internationally who

can represent the subject both physically and scholastically at a

high level while also possessing deep knowledgeable of other martial

traditions.)

But

the point is that there was a real prejudice in the misguided (though

well-intentioned) assumption by the Union's founders that every martial

art tradition comes to exist only within individual nation states

or is limited to one ethnic grouping. It's taken considerable effort

on my part to communicate to my fellow delegates the fact that historically,

the martial arts of Renaissance Europe, though regional, were largely

transnational. It's current study and recovery transcends any one

country, nation, ethnic body, or organization. But

the point is that there was a real prejudice in the misguided (though

well-intentioned) assumption by the Union's founders that every martial

art tradition comes to exist only within individual nation states

or is limited to one ethnic grouping. It's taken considerable effort

on my part to communicate to my fellow delegates the fact that historically,

the martial arts of Renaissance Europe, though regional, were largely

transnational. It's current study and recovery transcends any one

country, nation, ethnic body, or organization.

The

pleasant irony to all this is of course that the supposedly traditional

Asian martial arts are themselves the beneficiaries of the spread

of a global culture that has given them such international recognition

and popularity over the past six decades or so. It was only modern

international trade, travel, and communication that brought about

such an exchange. Even more so, there are many delegates in the WoMAU

from European and Middle Eastern countries who represent specific

Asian martial art styles that were only introduced to their countries

in the mid 20th century. In that regard, they can hardly be called

the "traditional" fighting art of those nations, let alone be considered

in any way indigenous (though they do reflect modern aspects of their

parent styles). By contrast, unlike Renaissance martial arts study,

the various member styles of the WoMAU also enjoy official state sanction

and government subsidy on behalf of their country of origin. Their

fighting styles are considered to embody intangible cultural heritage

of their nations —regardless of what minority portion in their society

actually studied them in the past. The

pleasant irony to all this is of course that the supposedly traditional

Asian martial arts are themselves the beneficiaries of the spread

of a global culture that has given them such international recognition

and popularity over the past six decades or so. It was only modern

international trade, travel, and communication that brought about

such an exchange. Even more so, there are many delegates in the WoMAU

from European and Middle Eastern countries who represent specific

Asian martial art styles that were only introduced to their countries

in the mid 20th century. In that regard, they can hardly be called

the "traditional" fighting art of those nations, let alone be considered

in any way indigenous (though they do reflect modern aspects of their

parent styles). By contrast, unlike Renaissance martial arts study,

the various member styles of the WoMAU also enjoy official state sanction

and government subsidy on behalf of their country of origin. Their

fighting styles are considered to embody intangible cultural heritage

of their nations —regardless of what minority portion in their society

actually studied them in the past.

Regardless

of all this, what the Union delegates of different styles and nations

share in common is a sincere love and respect for martial arts in

all its diversity, and the goal of educating how it is an important

part of the humanities. We all come together in celebrating both the

distinctions and similarities among the world's martial cultures and

the mutual challenge faced by preserving traditions in the modern

world. I never heard anyone ever express that their martial art was

black or brown or yellow or “non-white”. Same goes for anyone ever

saying their fighting style was Taoist or Islamic or Buddhist or Christian

(indeed, it would be inappropriate). Though the delegates have their

own private and public curricula, and in many cases their individual

style is hardly the only art from the country they represent, they

nonetheless stand in for all of them. Regardless

of all this, what the Union delegates of different styles and nations

share in common is a sincere love and respect for martial arts in

all its diversity, and the goal of educating how it is an important

part of the humanities. We all come together in celebrating both the

distinctions and similarities among the world's martial cultures and

the mutual challenge faced by preserving traditions in the modern

world. I never heard anyone ever express that their martial art was

black or brown or yellow or “non-white”. Same goes for anyone ever

saying their fighting style was Taoist or Islamic or Buddhist or Christian

(indeed, it would be inappropriate). Though the delegates have their

own private and public curricula, and in many cases their individual

style is hardly the only art from the country they represent, they

nonetheless stand in for all of them.

In this regard, one has to admire a South Korean program

that offers free scholarships to youths from around the world to come

study Korean martial arts without promotion of any ethnic, ideological,

or cultural agenda other than the benefits of fitness and discipline.

They are sharing their martial culture with pride, charity, and good

will.

It's actually a curious phenomenon: that the rise

of global pop culture, mixed martial art sports, and eclectic fighting

styles has caused traditionalists to band together and share what

was once exclusive and private, all in the understanding that representation

is stronger when done as a group. In doing so, in celebrating and

promoting, we've come to see things as less about specific "ancestry"

than it is about our general forebears of different cultures being

members of a human species. (Interestingly enough, this is something

I've always taken as tacit acknowledgment that true diversity is only

intellectual and cultural). Our "forebears are literally those who

came before us and by that regard we share a common human heritage."

Ultimately,

recognition of the universal elements of martial arts practice among

peoples around the world teaches an appreciation for both our differences

and commonalities that serves to remind us of our shared humanity.

It's absolutely right to feel a certain sense of pride when you feel

some type of cultural or ancestral connection to some positive achievement

and accomplishment that contributed to human civilization. But those

feelings should not arise merely because you see some familial or

ethnic lines at work, but only because you personally share the very

values and virtues of those contributions. The difficulty in this

comes when doing so requires us to weigh the historical context for

admiration against our own modern perspectives of what we consider

values. Ultimately,

recognition of the universal elements of martial arts practice among

peoples around the world teaches an appreciation for both our differences

and commonalities that serves to remind us of our shared humanity.

It's absolutely right to feel a certain sense of pride when you feel

some type of cultural or ancestral connection to some positive achievement

and accomplishment that contributed to human civilization. But those

feelings should not arise merely because you see some familial or

ethnic lines at work, but only because you personally share the very

values and virtues of those contributions. The difficulty in this

comes when doing so requires us to weigh the historical context for

admiration against our own modern perspectives of what we consider

values.

One

of my students in Asia once said they were asked by someone in their

country why they were studying a Western martial art rather than a

native one and he told me that without a moment's hesitation he replied,

"Why not? They study ours." He added that no one should try to make

him feel he had to defend his preference any more than he had to defend

that he was interested in Western movies, music, novels, or food.

He's absolutely right. There is an absurd assertion sometimes pushed

by radicals that anytime you celebrate or enjoy aspects of another

ethnic culture you're somehow doing so without "permission" when what

you are really doing is recognizing and sharing in it as something

of value for everyone. One

of my students in Asia once said they were asked by someone in their

country why they were studying a Western martial art rather than a

native one and he told me that without a moment's hesitation he replied,

"Why not? They study ours." He added that no one should try to make

him feel he had to defend his preference any more than he had to defend

that he was interested in Western movies, music, novels, or food.

He's absolutely right. There is an absurd assertion sometimes pushed

by radicals that anytime you celebrate or enjoy aspects of another

ethnic culture you're somehow doing so without "permission" when what

you are really doing is recognizing and sharing in it as something

of value for everyone.

Renaissance

masters and schools of defence did discriminate in who they taught

fighting skills to —and rightly so. But they did it based upon whether

a person was of poor character, questionable virtue, or criminal inclination

—which is something every reputable combat art does. As a historian

and a teacher I don't see it as my job to do anything other than present

the original martial material accurately as much as is possible, and

do so with regard to its original physical and mental context. In

this case, I believe that means without regard to anything except

for its principles, concepts, and ethics of self-defense. The sources

for Renaissance martial arts teachings do not refer to themselves

and their Art "racially" and thus neither will I. Those who have a

need to do differently are not going to find a sympathetic place in

our fellowship.

It's said that heritage is a matter of descent, really.

We're all every one of us descended from some people from somewhere. Go back far enough and we're all interrelated. Go back

only a short while and it hardly matters. I sympathize with the sentiment

that there is a certain "unspoken rule that only non-Occidentals be allowed to

express any 'civilizational consciousness'." At some point this is going to have to be acknowledged, one way or another. But it is shared values and the virtues of shared ideas that binds us beyond kin.

I have long been proud that our club,

the ARMA, was the first, and still one of the few, to affirm for its

members a specific Credo of Renaissance martial arts studies: Respect

for History and Heritage,  Sincerity

of Effort, Integrity of Scholarship, Appreciation of Martial Spirit,

and Cultivation of Self-Discipline. Note that first phrase includes

the word "heritage" —which is about the thing that we as moderns inherited

from the past. It is not referring to something that was kept within

a family, a tribe, a clan, nation, state, or a "race." It is about

educating ourselves in the inheritance of history, of lessons about

who and what came before us regardless of who we ourselves are or

where we came from. Ancestry is not necessarily your heritage, and

your heritage need not be ancestral. Sincerity

of Effort, Integrity of Scholarship, Appreciation of Martial Spirit,

and Cultivation of Self-Discipline. Note that first phrase includes

the word "heritage" —which is about the thing that we as moderns inherited

from the past. It is not referring to something that was kept within

a family, a tribe, a clan, nation, state, or a "race." It is about

educating ourselves in the inheritance of history, of lessons about

who and what came before us regardless of who we ourselves are or

where we came from. Ancestry is not necessarily your heritage, and

your heritage need not be ancestral.

All the world’s martial arts represent parts of our shared global

history. So, celebrate and respect your heritage whenever and wherever

you find virtue in it, but let others do the same with it as well.

Heritage is as global as it is personal.

|