Martialists and the "Arts of Mars" Martialists and the "Arts of Mars"

Historical origins of a familiar term

By John Clements

ARMA Director

As a student of martial history and professional instructor, I have often posed a simple question: What is the origin of the familiar term “martial arts”? The answer is little known and seldom appreciated.

"Now, that I am able to prove it,

let but any martialists read this discourse,

and lay aside all prejudicary of opinion

--A Warre-like Treatise of the Pike

Donald Lipton, 1642

Naming the Noble Art and Science of Defence

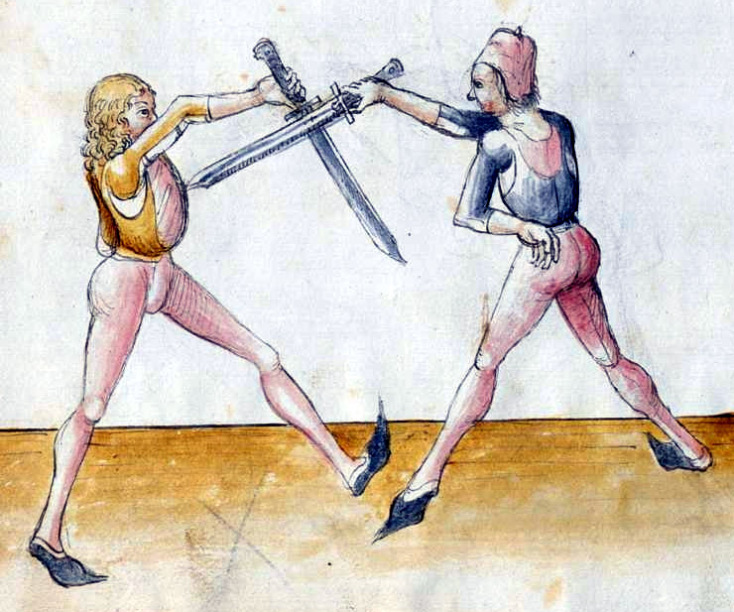

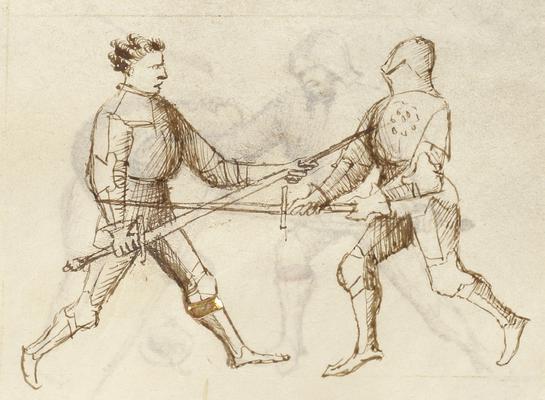

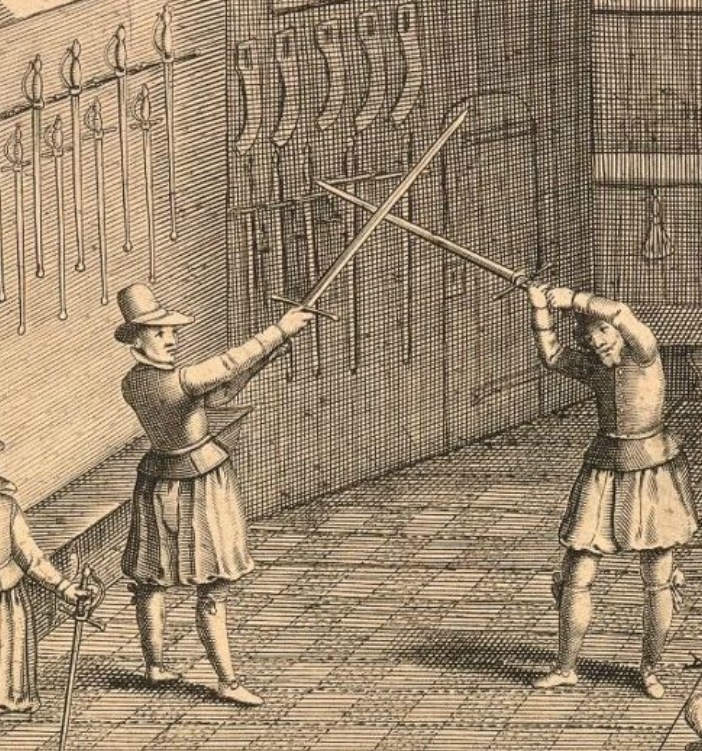

The systematic fighting disciplines of Renaissance Europe

as documented in well over a hundred fight books from the late 14th

through mid-17th centuries employed a wide assortment of names among

European languages to identify their combat disciplines, self-defense

systems, and “warlike exercises”.

These names included: the Disciplina Armorum, the Doctrina Armorum, Arte Gladiatoria, Art Battaglia, the Art Dimicatorie, arte del combattere, La Destreza de la armas, La noble science, the Noble and Worthy Science of Defence, and the Art of Defence. Most all of the major 14th through 16th century Germanic martial arts sources simply called it Kunst der Fechterey or Kunst des Fechten.

This diversity of names was reflective of how knowledge in the

Renaissance was being explored and systemized. Earlier, the knightly

classes of the early Middle Ages had christened their fighting methods

the “chivalric art” and the “art of chivalry” (or even la scienza cavalleresca).

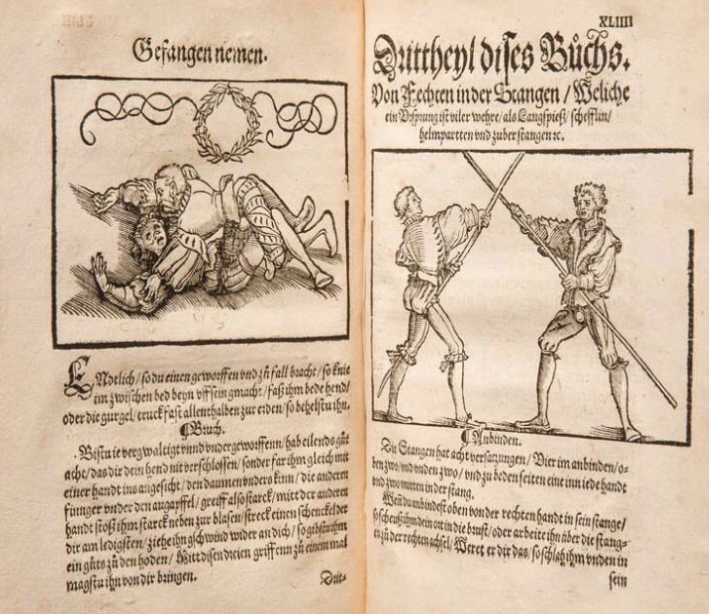

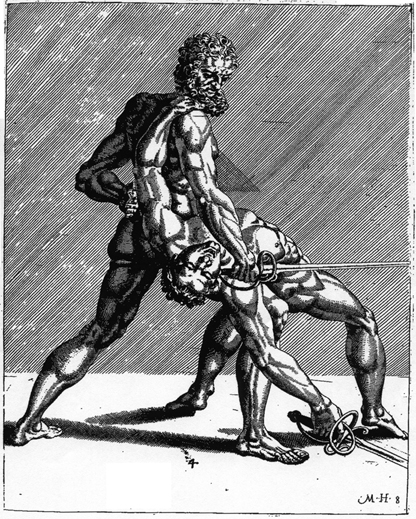

Virtually every Italian fencing master writing during the

15th and 17th centuries had a different regional term for his craft of

“fence”. The master Fiore die Liberi referred in his fight treatise of

circa 1409 to any fighting system variously as L’arte D’armizare, or “the art of bearing arms”, though his unarmed method he described as abrizzare. The master Filippo Vadi, in his treatise from circa 1482, called the craft, De arte gladiatoria dimicandi. Although, the noted knight, Pietro Monte, referred to his 1509 assemblage of teachings as the artis militaris

specifically because it consisted of the primary skills a knight needed

for war. In his 1536 work, maestro Achille Marozzo named it as Arte de le Armi, while Maestro Giacomo Di Grassi named the craft of fighting as l’arte di adoprar l’arme

in his work of 1570 (labeled “this true and honorable Art or Science” in the 1594 English version). The Disciplina gladiatorial was defined by Nicholas Udall in his 1533 work, Flowers of Latine Speaking, as “the precepts and way of trainying men in the weapons, and the

schooles that maysters of fence keeps.” Along with many others, maestro Niccolo Giganti in his 1606 treatise called it l'arte di Scherma. Later, the master Capo Ferro in 1610 labeled it Arte della scherma, reflective of the shift from broader military skills to a focus on dueling. Virtually every Italian fencing master writing during the

15th and 17th centuries had a different regional term for his craft of

“fence”. The master Fiore die Liberi referred in his fight treatise of

circa 1409 to any fighting system variously as L’arte D’armizare, or “the art of bearing arms”, though his unarmed method he described as abrizzare. The master Filippo Vadi, in his treatise from circa 1482, called the craft, De arte gladiatoria dimicandi. Although, the noted knight, Pietro Monte, referred to his 1509 assemblage of teachings as the artis militaris

specifically because it consisted of the primary skills a knight needed

for war. In his 1536 work, maestro Achille Marozzo named it as Arte de le Armi, while Maestro Giacomo Di Grassi named the craft of fighting as l’arte di adoprar l’arme

in his work of 1570 (labeled “this true and honorable Art or Science” in the 1594 English version). The Disciplina gladiatorial was defined by Nicholas Udall in his 1533 work, Flowers of Latine Speaking, as “the precepts and way of trainying men in the weapons, and the

schooles that maysters of fence keeps.” Along with many others, maestro Niccolo Giganti in his 1606 treatise called it l'arte di Scherma. Later, the master Capo Ferro in 1610 labeled it Arte della scherma, reflective of the shift from broader military skills to a focus on dueling.

Naming of self-defence methods or fighting disciplines

actually has a long history in Western civilization. In an 1871

translation of Plato’s Dialogues, the conversation between

Theodorus and the Stranger discussing a “Sophist”, we find: “There was a

subdivision of the combative or fighting art...” (Jowett, p.485) Thus,

there was an assortment of terms used for combatives among European

languages, and for early English, most notably: the chivalric art, the

art of fence, and the noble science. Given that there were such diverse

ways to identify regional and national fighting methods, no reason

emerged to call the subject by a common universal term. But the key

question is, were any of them ever called a “martial art”? Naming of self-defence methods or fighting disciplines

actually has a long history in Western civilization. In an 1871

translation of Plato’s Dialogues, the conversation between

Theodorus and the Stranger discussing a “Sophist”, we find: “There was a

subdivision of the combative or fighting art...” (Jowett, p.485) Thus,

there was an assortment of terms used for combatives among European

languages, and for early English, most notably: the chivalric art, the

art of fence, and the noble science. Given that there were such diverse

ways to identify regional and national fighting methods, no reason

emerged to call the subject by a common universal term. But the key

question is, were any of them ever called a “martial art”?

Presenting the Evidence

Although self-evident, it is surprising how little known

the fact is that the now common English term “martial arts” is actually

from the Latin, artes martiales (or even ars Martialis), as in the “Arts of Mars”, the Roman god of war (Martius). The word Ars can mean skillfulness or proficiency and artes

refers to skills or ability. They denoted a craft, technique, or

systematic body of knowledge acquired through practice and study in

contrast with that from innate talent or aesthetic creation. Thus, we

properly read martial art as “craft” and “skill”, more so than

“artistry” (a notable distinction to how the term has come to be

applied).

As we still lack direct evidence for Roman use of the term artes martiales,

it may well be that the English phrase “martiale arte” was formed in

the late 15th century and then became more common in the early 16th

century by a natural and logical conjoining of the two words. The Early English Text Society edition (1926) of The Book of the Ordre of Chyvalry —transcribing

the original 1489 William Caxton English text from the British Library

copy— reads: “For the noble and merveillous science and arte marcialle,

the whiche a knyght ought to have in knowleche and in usage.” (Although

Caxton was translating a 15th century French version of Ramon Llull’s

earlier 13th century Catalan work, none of the earlier versions included

forms of the term.)

In a work published in the year 1521, Henry Bradshaw

composed the following verses on the life of Saint Werburge: “In all

artes Marcyall, ever havynge the vyctorye, With herte, mynde, and

harneys, redy day and nyght, Theyr enemyes to subdue, by power mayne

& myght.” (Bradshaw, Line 229, p.16)

Yet, the earliest direct use of the term martial art in

English may in fact be in a 1557 poem by Henry Howard, the Earl of

Surrey: “In war, that should set princely hearts on fire, Did yield

vanquisht for want of marcyall arte.” (Howard, p.64)

As well, the Portuguese lyrical poet Luis De Camões, in his Lusiads of 1572 referred to seeing “the civill Arts, and Martiall.” (Bullough, p.245) The

term further appeared in regard to general military training as early

as 1579 in one English treatise on the subject (Gates, p. 35-36). Sir

William Drury’s 1570 Rode Into Scotland, also states, “to foster and norishe this crue of men in the marſhall arte and rules of warre.” (Churchyard, p.101)

In referring to the armed citizen of the “trained bands of

London” during the early 1500s, John Strype’s updated 1698 version of

John Stow’s original 1598 survey of the city during the time of Henry

VIII, we read how civic authorities “hath her members carefully

disciplined in Martial Arts, and Feats of War, for that Purpose.”

(Strype, p.566) Curiously, Stow, had also described ‘the art gladiatorie

or science of defence”, when referring to “professors” of the “noble

science”, adding “or masters of fence, as we commonly call them.”

A 1581 sonnet by the noted Flemish author and military officer, Alexandre van den Busche, opens with the line: Puis que l’art martial & force militaire...”

(Busche, p.67) Though its use undoubtedly alludes to craft of warfare

rather than self-defence skills, the two were still seen as blended at

this time and l’art martial appears in other works. We find it

again in the 1590 poem, “Conquista de la Betica”, by Juan de la Cueva,

as: “la guerrera A quien enseña Amor la marcial arte” —“the warrior to

whom love teaches the martial art”. (Cueva, p.177) A 1581 sonnet by the noted Flemish author and military officer, Alexandre van den Busche, opens with the line: Puis que l’art martial & force militaire...”

(Busche, p.67) Though its use undoubtedly alludes to craft of warfare

rather than self-defence skills, the two were still seen as blended at

this time and l’art martial appears in other works. We find it

again in the 1590 poem, “Conquista de la Betica”, by Juan de la Cueva,

as: “la guerrera A quien enseña Amor la marcial arte” —“the warrior to

whom love teaches the martial art”. (Cueva, p.177)

A manuscript treatise on military affairs by Sir Henry Lee

from circa 1603 employed a dialogue between two fictitious characters

named Ricado and Allounso that featured the following line: “of this

Martial Arte, to command all others to the quiet and disquiet”. (Jordan,

p.106). John of Ney’s 1607 Warres Testament expressed: “Bequeath my goods, and all that I possesse, And teach all these that Martiall Art professe.” The 1614, Lucan’s Pharsalia,

of Nicholas Okes, describes: “By martiall art and valour showne; They

would not then have headlong prest, To fight a Battaile for their rest.”

Walter Quin’s 1619, The Memorie of the Most Worthie and Renowned Bernard Stuart,

noted: “to act his part, done by acts of Martiall art and went about to

win, did so much excell therein, the valiant’st Knights renown'd.”

Sir John Oglander told of a company of youths “practicing

martial arts” (likely pike and musket drill) on the Isle of Wight in

1627, and again in 1634. (Grafton & Blair, p. 220). And in the 1631,

The Legend of Captaine Jones, David Lloyd wrote: “This know, in

thy old age thou shalt impart, Unto thy Countries youth thy martiall

art, Teach them to manage armes, and how they must make bright their

swords, which peace hath wrapt in rust.”

Examples like this fill 16th and 17th century English

poetry as the term was used with regularity in verse when referring to

martial prowess, martial deeds, martial feats, and martial skill. As

first described by this author in a 1998 published work, the term

“martial art” appears notably with specific regard to fencing in a

laudatory from the anonymous 1639 English swordplay treatise, Pallas Armata, Or the Gentleman’s Armory:

Thou herein to the reader do impart

In a plain way that famous martial art

Of fencing, which by charge and toil some pain

Thou have attain’d, and strive to make us gain

Instances such as these go on and on and can be found

throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly in the era’s poetic

works and military treatises when describing either a self-defence

method or skills for the battlefield. Within a 1598 English translation

of the 1564 work, Diana Enamorada, by Gaspar Gil Polo, we

discover the lines: “Bruted with living praise in every part: Whom I may

well for golden verse compare, To Phebe, to Mars in armes and martiall

art”. William Stirling’s 1614 poem, Domes-Day, expressed:

“some states did strive how to be great, By morall vertues, and by

martial arts, Till colder climats did control that heat, Both showing

stronger hands, and stouter hearts…” The 1651 heroic poem, Gondibert, by

Sir William D'Avenant also contains the verse: “the martial art of

constraining is the best, which assaults the weaker part…”. Instances such as these go on and on and can be found

throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly in the era’s poetic

works and military treatises when describing either a self-defence

method or skills for the battlefield. Within a 1598 English translation

of the 1564 work, Diana Enamorada, by Gaspar Gil Polo, we

discover the lines: “Bruted with living praise in every part: Whom I may

well for golden verse compare, To Phebe, to Mars in armes and martiall

art”. William Stirling’s 1614 poem, Domes-Day, expressed:

“some states did strive how to be great, By morall vertues, and by

martial arts, Till colder climats did control that heat, Both showing

stronger hands, and stouter hearts…” The 1651 heroic poem, Gondibert, by

Sir William D'Avenant also contains the verse: “the martial art of

constraining is the best, which assaults the weaker part…”.

From Samuel Butler’s satirical fantasy poem, Hudibras,

(c.1660-1680) we amusingly read: “For those that fly may fight again,

Which he can never do that’s slain. Hence timely running’s no mean part,

Of conduct in the martial art” (lines 243-246). And: “Then, like a

warrior right expert, And skilful in the martial art, The subtle Knight

straight made a halt, And judg’d it best to stay th’ assault” (lines

709-712).

In his 1672 edition of the great 1st century Latin poem, Punica,

by Sirius Italicus, Thomas Ross translated the section about Varro as:

“To plead, so was he weak in Martial Arts, And neither fam’d for

Courage, nor for Parts.” (Italicus, p.222). George Granville’s, Poems upon Several Occasions,

dated between 1685 and 1688, addressed James II with the opening lines:

“Tho’ train’d in Arms, and learn’d in Martial Arts, Thou chusest not to

conquer Men, but Hearts…” In the prologue of Thomas Plunket’s 1689

tract on the character of a battlefield leader we find: “Then,

good Commanders would be priz’d indeed, For they are precious in a time

of need. But, I mean such, as in the Martial Art, Have skill acquired by

the Practick Part, Or long experience in the art of War.” Within the

1689, “Remarques on the Life of the Great Abraham” from Ta kannouku, by Stephen Jay, we find, “Now will he Exercise him in the Martial Art of fighting”. (Jay, p.56)

Translating the tragedies of Seneca in 1702, Sir Edward

Sherborne’s edition included the following line by Pyrrhus:

“of Achilles, who, besides his Martial Arts, was train’d up

by Chiron, in physic and music”. In a similar verse from the poem, Leonidas,

written in 1737 about the Spartans at Marathon, Richard Glover included

the lines, “O’er Asia’s armies, and our courage boast, Our martial art

above the vulgar herd?” As well, a poem on the death of the Duke of

Gloucester published in 1763 by the Lady Chudleigh, included the

eloquent lines: “Sweet was his Temper, generous his Mind, And much

beyond his Years, to Martial Arts inclined”. (Sherburne, p.252) Another

source from 1773 translated an 11th-century Irish author as writing:

“The warlike king of Ulster: the third, A prince for letters and for

martial arts…” (Vallancey, p.183)

The term arte marcial is also used as a synonym for

“art military” in Spanish works on military architecture and geography

by the battle general, Don Sebastian Fernandez De Medrano, that were

first published in 1700. (A 1902 Spanish work was even still applying arte marcial

to general military skills to be taught at a royal academy!). In most

all these later cases they were referring to the traditional military

skills of personal close-combat that were equally used in civilian

self-defense and private duel just as they had in the Medieval and

Renaissance eras, if not well before.

In Deference to Mars

Allusion

and reference to the classical idea of Mars as progenitor of all things

warlike and military fill the civilization of the Renaissance. The

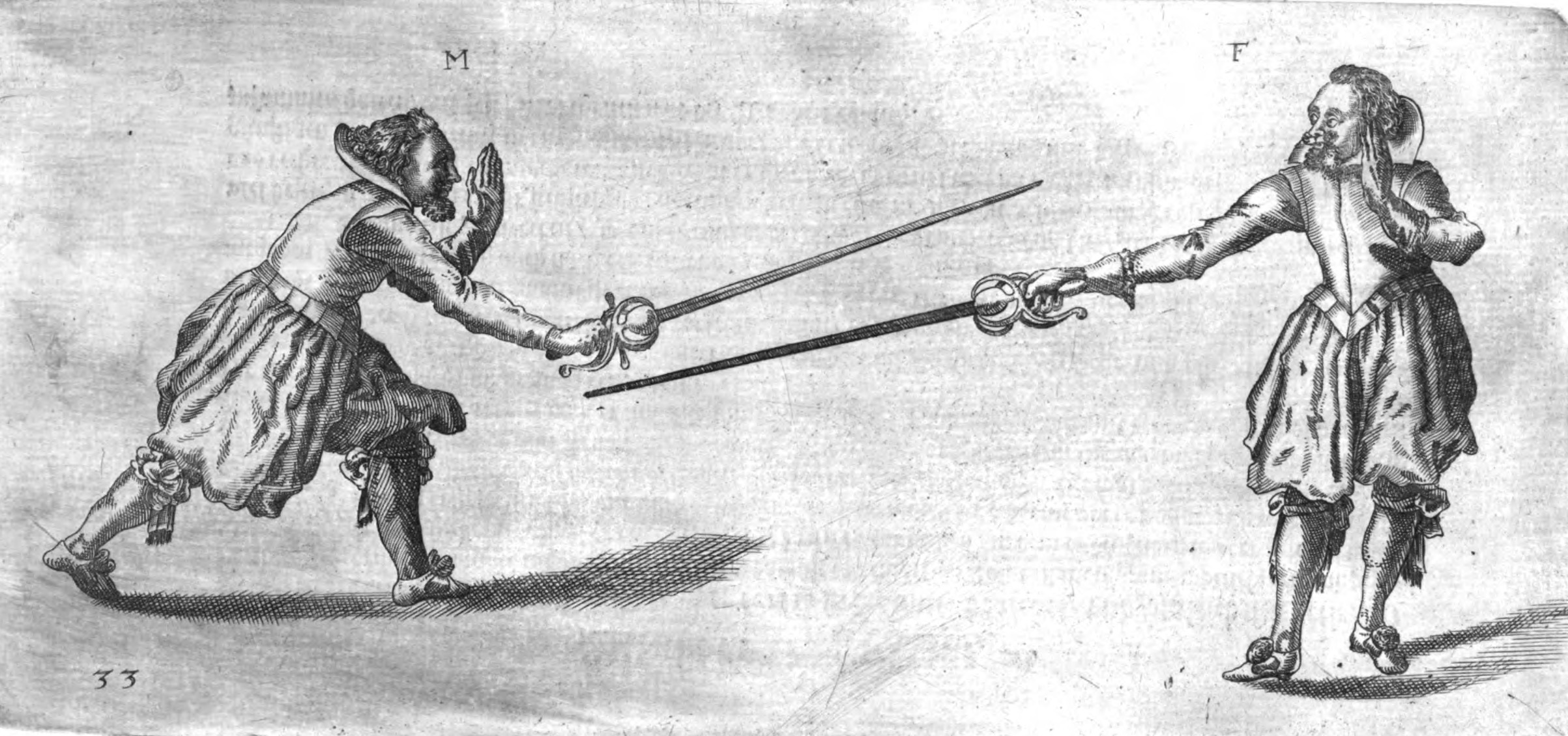

opening page of Henri de Sainct Didier’s 1573 fencing treatise states:

“…the single sword, mother of all weapons…to defend and attack at the

same time from the blows that can be struck, both in attacking and

defending, very useful and profitable for training the nobility, and the

followers of Mars...” Allusion

and reference to the classical idea of Mars as progenitor of all things

warlike and military fill the civilization of the Renaissance. The

opening page of Henri de Sainct Didier’s 1573 fencing treatise states:

“…the single sword, mother of all weapons…to defend and attack at the

same time from the blows that can be struck, both in attacking and

defending, very useful and profitable for training the nobility, and the

followers of Mars...”

Interestingly, the phrase “arts of mars” appeared

frequently in a poetic context starting in the late 15th century and

continuing well into the 19th. In his 1498, The Bowge of Courte,

John Skelton, an English poet known for satirical verse, wrote: “With

the art of Mars he was not all acquaint.” Similarly, in the 1558, Les Regrets, the French poet Joachim Du Bellay used Mars symbolically paired with Athena for wisdom: Les arts de Mars et de Pallas ensemble (“The arts of Mars and Pallas together”). In a 1553 poetic work, Admiranda quaedam poemata, Johann Bockenrode directly employed the expression, experiamur artes Martis or “let us try the arts of Mars”. As well, the 1564 polished Latin text of the humanist Joannes Sambucus’ Emblemata (printed in Antwerp) reads: Mars armipotens, cui nulla ars ignota martialis est... (“Mars, mighty in arms, to whom no martial art is unknown...”).

Torquato Tasso’s epic 1581 Italian poem, Gerusalemme Liberata, also invokes the term when referring to a knight’s fighting prowess, as Canto IX, Stanza 22 reads: L’arte di Marte in lui si vede intera (“The art of Mars in him is seen entire”). Cervantes’ own Don Quixote of 1605 mentions “las artes de Marte” only in early translations or glosses (e.g., 17th-century Latin editions), while the Spanish original uses cosas de guerra (“things of war”). From the frontispiece of Hans Wilhelm Schoeffer von Dietz’s fighting work from 1619, we find the lines: En via strataibiest: submetolerare Magistro Dice Artis & Martis labriosum opus. Thus, he commends us to to “study the Arts of Mars, a laborious process.” The Latin phrase, in artibus Martis (“in the arts of Mars”) also appears in the 1647 work by Andreas Magrius, Controuersiarum iuris volumen quartum.

An obscure Latin poem by Wolfgang Jacobius written in 1593 to

commemorate graduates in liberal arts and philosophy at Ingolstadt

University, beautifully expressed the Renaissance humanist view of the

relationship between war and art: “Clearly, Art calls Mars under its own

laws, Art cultivates Mars, and the beautiful contest of honor, Here

engaged; let it also be the work of Art and Mars… You will perform the

tasks of Mars, by speaking to conquer Mars, By which skillful Art makes

for itself...” (Jocobius, p.10) This sentiment of art providing the

wisdom to control and guide the martial was again expressed poetically

in the 1611, Centuria anagrammatum prima by Petrus Ailberus: “Art

needs Mars; conversely, Mars needs Art. Through Art and Mars comes

glory… Mars is Art’s companion: hence you will be a soldier of both Mars

and Art.” (Ailberus, p.146-147)

Most interestingly, in 1639, the Duke of Newcastle

referred directly to the then “science of defence” when advising in his

writings on rapier fencing that, “all Gentlemen should learn the Arts of

Mars.” Then, in 1662, Lady Cavendish, the Duchess of Newcastle,

produced a book of her plays that included the following statement by

Lady Victoria from Bell in Campo: “take that which fortune shall

profer unto us, let us practise I say, and make these fields as schools

of martial arts and sciences, so shall we become learned in their

disciplines of war.” (Cavendish, p.590) Given that her own husband had

himself written a detailed fencing treatise on the Noble Science in the Spanish style years earlier, there can be no questioning her deliberate use of the term. Most interestingly, in 1639, the Duke of Newcastle

referred directly to the then “science of defence” when advising in his

writings on rapier fencing that, “all Gentlemen should learn the Arts of

Mars.” Then, in 1662, Lady Cavendish, the Duchess of Newcastle,

produced a book of her plays that included the following statement by

Lady Victoria from Bell in Campo: “take that which fortune shall

profer unto us, let us practise I say, and make these fields as schools

of martial arts and sciences, so shall we become learned in their

disciplines of war.” (Cavendish, p.590) Given that her own husband had

himself written a detailed fencing treatise on the Noble Science in the Spanish style years earlier, there can be no questioning her deliberate use of the term.

Amusingly

enough, in a 1651 dedicatory poem to a friend, The Marriage of Armes

and Arts, Robert Whitehall wrote: “So Ars and Mars by an Aphaeresis

become the very same.” (Apheresis is the phenomenon in phonetics and

phonology whereby a sound change is made to a word by dropping the

initial vowel; hence, in this case, removing the “M” from Mars so that

it becomes Ars.)

Martial Science?

So, what have we learned so far? The original use of the

English term “martial arts” and its assorted antecedent “artes Marcyall”

is now somewhat self-evident. The term begins to emerge in the late 15th

century and was indeed employed frequently in discourses throughout the

16th century to denote both knightly prowess in arms and general

military skill of soldiers.

It is readily apparent how often the art of defence was

also labeled the science of defence. In many cases a fight master simply presented

general ideas on fighting (the “science”) supplemented with

elements from their own method and original observations (the “art”).

In a sense then, the science of defense involves general principles, the

governing “rules” or “laws”, underlying the fighting that is performed

as an art of defence.

In this same way, very often

“martial science” was essentially used synonymously with “martial art.”

At the time, the word syence or scientia essentially meant knowledge, whereas Ars meant skillfulness or proficiency and artes

referred to skills or ability. Thus, prowess in a systematic

self-defence method was viewed as being both a science and an art, much

as were other crafts in Western Christendom such as music or medicine.

Why a combat system would be described as both art and science at the

time and seen as blending is easy enough to understand: It is an art

because it involves application of personal skill and talent, but it is a

science because it involves knowledge of guiding principle or rules. In this same way, very often

“martial science” was essentially used synonymously with “martial art.”

At the time, the word syence or scientia essentially meant knowledge, whereas Ars meant skillfulness or proficiency and artes

referred to skills or ability. Thus, prowess in a systematic

self-defence method was viewed as being both a science and an art, much

as were other crafts in Western Christendom such as music or medicine.

Why a combat system would be described as both art and science at the

time and seen as blending is easy enough to understand: It is an art

because it involves application of personal skill and talent, but it is a

science because it involves knowledge of guiding principle or rules.

For example, while by 1480 the master Filippo Vadi declared that, because it was based on geometry, the craft was a true science and not an art, he nonetheless referred to it as both. Geoffroi de Charny’s mid-14th century, Livre de la Chevalerie, also referred to the craft as “science des armes.” Bernhard von Breydenbach’s 1489, Le Saint voiage et pélerinage de la cité sainte de Hierusalem, contains a key phrase, la science et discipline de bien bataillier,

that translates to “the science and discipline of good fighting in

battle.” Regarding Henry VI, we read how “he ordred his battail, like a

man expert in marciall science” (Hall, p.151)

In an anonymous book from 1549, The Complaynt of Scotland, we find the line, “for every man may marvel of his dexterity, virtue, and martial science” (p.5r). The 1549, Dictionnaire François-Latin, by Robert Estienne listed science d'art militaire, while Master Henri de Sainct-Didier’s 1573 fencing treatise described his craft as being about the science du combat. In 1553, Maestro Cammillo Agrippa called it Scientia d’arme,

as several others did earlier. In 1606, rapier fencing is described by

master Giganti as “the science of the sword, or of arms…a speculative

science.” Master Fabris in his 1606 rapier treatise also called it

Sienza e Pratica d'Arme, “science and practice of arms”.

The little known 1635 poem, Pyrgomachia,

described mock bouting at a masque for James I as: “The Castle-Combat.

Performed by James Fencer and William Wrastler.” It then labeled the

exhibition one of “The Martial Science of Defence”. Johann Jacob “von” Wallhausen, who emphasized instruction for military

foot combat in his 1615, L'Art Militaire pour L'Infanterie, stated: “It

is an art or science to wage war well, or if you prefer, in Latin, Ars

militaris est scientia bene bellandi.” (Military art is the science of

good warfare.)

Surprisingly, more so than martial art, the term “martial

science” appears to have been more commonly employed in the Renaissance,

but only in relation to what was later to be called military science.

In fact, starting in the 18th century and increasing through the 19th,

“the martial art” was frequently employed as a synonym for “the military

art”. Well into the early 20th century “the martial art” can still

be found being used as a general way to label effective military

capacity. The abundance of such examples are too

extensive to begin doing them justice, but the pattern continued to

where the term was then often synonymous with “military science” (but

that is another story). Interestingly enough, an 1884 article in the

Daily Ardmorite paper of Oklahoma, called pugilism a “martial science”,

whereas in the previous century it was common to call boxing a “Science

of Self Defence”. [“Science of defense”

even continued to be used well into the 19th century, sometimes as a synonym

for boxing or pugilism, sometimes for fencing, and sometimes even for

military science, but these details are not pertinent here]. Surprisingly, more so than martial art, the term “martial

science” appears to have been more commonly employed in the Renaissance,

but only in relation to what was later to be called military science.

In fact, starting in the 18th century and increasing through the 19th,

“the martial art” was frequently employed as a synonym for “the military

art”. Well into the early 20th century “the martial art” can still

be found being used as a general way to label effective military

capacity. The abundance of such examples are too

extensive to begin doing them justice, but the pattern continued to

where the term was then often synonymous with “military science” (but

that is another story). Interestingly enough, an 1884 article in the

Daily Ardmorite paper of Oklahoma, called pugilism a “martial science”,

whereas in the previous century it was common to call boxing a “Science

of Self Defence”. [“Science of defense”

even continued to be used well into the 19th century, sometimes as a synonym

for boxing or pugilism, sometimes for fencing, and sometimes even for

military science, but these details are not pertinent here].

The earliest use of the Latin word scienta could mean awareness, knowing

and collected knowledge, with “science” in use as such by the 14th

century. The word appears to have first appeared in the writings of

Marco Terentius Varro in early 1st century BC. The Oxford English

Dictionary states that the oldest English sense of the word now is

restricted to theology and philosophy adding that from late 14th century

it (appropriately enough) meant “book-learning” also "a particular

branch of knowledge or of learning, systematized knowledge regarding a

particular group of objects.” But it also was used to describe

“skillfulness, cleverness; craftiness.” From at least circa 1400 as

“experiential knowledge” also “a skill resulting from training,

handicraft; a trade.” Even further, it could mean “assurance of

knowledge, certitude, certainty” and also methodical observations or

propositions, or methods for effecting practical results (tekhnē). All

of this certainly applies to the Renaissance conception of the Arts of

Mars where science is sometimes used for practical applications and art

for applications of skill.

In general, being

both for military battlefield use as well as personal self-defence,

combat skills among the noble classes were sometimes simply called the

knightly craft or the chivalric art (although, virtually the same skills

and equipment were used by common men-at-arms.) An English manuscript

from c.1485, “The Ordinances of Chivalry” (BNL MS Harley 6149), refers

to the need for knights “to learn the art of war and of chivalry” (Folio

12v) and “the art and usage of arms” (Folio 14r). It calls “to use the

craft of a knight in defence of holy church.” The 1486 “Boke of Saint

Albans” refers to the “craft of armorye” itself as meaning the knowledge

of using weapons in battle.

The terms art and science became conflated and even

inverted from their Medieval and Renaissance usage. Science was seen as

that which had rules or laws that can be determined by observation,

experiment and replication. Increasingly, ‘art’ came to mean something

done with instinct, intuition and talent (even genius), not by rote,

reflection, or reasoning. The distinction can be seen as one of

theoretical ideas (abstraction and contemplation) contrasted with practical

application (ability or practice). If “science” is knowing, then “art” is

capacity.

There is a certain recognizable Aristotelian influence at work in how

Renaissance Masters of Defence structured their teachings. According to

Aristotle in his Nicomachean Ethics, there is a distinction between the

theoretical and the practical where “scientific knowledge (episteme) is

judgement about things that are universal and necessary, and the

conclusions of demonstration…” given “…that which can be scientifically

known can be demonstrated, and art and practical wisdom deal with things

that are variable.“ (Book VI, Chapter 6) What does a “science of

defence” aim to do other than reduce experiences down to fundamental or

universal rules? Thus. combat skills were essentially, approached as

scienta, in the meaning of principia in praticum —putting principles

into practice. It is in such implementation where the artistry in “the

art of defence” essentially lies.

What

we can most conclude from all of this is that the

Latin-derived term martial arts did not see wide adoption likely because

a host of pre-existing specific regional and national names for the art

and science

of personal self-defence were readily available. As writing in verse

form was not at all uncommon in the Medieval and Renaissance eras, it is

likely that the term’s frequent appearance in poetry was a reflection

of its popular use. What

we can most conclude from all of this is that the

Latin-derived term martial arts did not see wide adoption likely because

a host of pre-existing specific regional and national names for the art

and science

of personal self-defence were readily available. As writing in verse

form was not at all uncommon in the Medieval and Renaissance eras, it is

likely that the term’s frequent appearance in poetry was a reflection

of its popular use.

Mistakes and Mistranslations

There are a few notable claims oft cited for the term’s historical

usage that are in fact erroneous. From an account in

the Harleian Manuscripts (British Museum, 1312) of 15th century knights

at the English royal court, we intriguingly read: “The squires are accustomed,

afternoons and evenings, to gather in the lord’s chamber. There they

talk of chronicles of kings, pipe, harp, sing, or other martial arts, to

help to occupy the court.” (Peter Speed. Those Who Fought.

Italica Press, 1996, p. 99.) Unfortunately, Speed never gave a citation

for which specific Harleian was his source, and since it was very likely

written in French, his entry is highly questionable and has yet to be

verified. But the phrase, les arts martiaux, which did not apparently enter the modern lexicon until late 19th century at the earliest, is unlikely to have been the case.

Curiously, one oft-cited source from 1823 asserts that Richard

III writing of Eric of Richmond in the year 1485, described him as “a

man of small courage and less experience in martial art, and feats of

war: who never saw army, nor was exercised in martial affairs”. (Turner,

p. 538) However, from the historian and parliamentarian Edward Halle’s Chronicle

of 1548 the phrase actually reads as “marcyall actes and feates of

warr” —not “martial art” (Hall, p.415). The mistaken line was then

repeated in Charles Knight’s 1862, Popular History of England, Volume 2. Additionally, Richard Grafton’s original 1569, Chronicle At Large, also records Richard III as saying Eric was of less experience in “martiall actes”. (Grafton, p.847).

Similarly, Christine de Pisan’s 1410 The Book of Deeds of Arms and of Chivalry

supposedly states: “It is better…that young men should be excused for

not having entirely mastered the martial art than that they should be

reproached in old age for never having known it.” This quote appears

courtesy of the Willard’s translation published by Penn State in 1999

(p.30-33). However, no other earlier translation efforts of Pisan used

the phrase “martial art.” The original line is itself actually a

rephrased statement by the Roman writer Sallust —by way of Vegetius’s

famed 4th century work on the ars militari— and was only in

regard to lamenting how youths were yet too young to go to war while

mature men were too old to ever experience it. Similarly, Christine de Pisan’s 1410 The Book of Deeds of Arms and of Chivalry

supposedly states: “It is better…that young men should be excused for

not having entirely mastered the martial art than that they should be

reproached in old age for never having known it.” This quote appears

courtesy of the Willard’s translation published by Penn State in 1999

(p.30-33). However, no other earlier translation efforts of Pisan used

the phrase “martial art.” The original line is itself actually a

rephrased statement by the Roman writer Sallust —by way of Vegetius’s

famed 4th century work on the ars militari— and was only in

regard to lamenting how youths were yet too young to go to war while

mature men were too old to ever experience it.

Writing in 1845 on Spenser’s, The Fairy Queene, one

literary historian described how Prince Arthur is “delivered to a fairy

knight, who forthwith brought him…to be…instructed in all martial arts

and exercises…” (Knight, p. 163). Spenser’s original words in 1590

actually read: “deliver’d to a Fairy Knight, To be upbrought in gentle

thews and martial might…” (Canto IX). Still, the understanding is

implicit for the term martial arts by this time was referring directly

to knightly close combat skills, and Spenser later even mentions “deeds

of arms and prowess martial.”

Translation of Ancient Greek works done in the 18th and 19th centuries, of The Iliad

in particular, have also quite often misrepresented historical use of

the term, even as the original Greek words typically pertained only in

general to “warlike skills” or “war techniques”. Similar errors can be

found in incorrectly reading historical references to the Roman poet

Martial (or Marshal —itself not to be confused with the law enforcement

title).

More recently, there has been a somewhat tendentious

—though not strictly inaccurate— habit among modern translators of the

large body of Renaissance-era martial arts literature to substitute

various historical phrases into the more easily understood one of

“martial art”. For example, in the 1569, De Arte Gymnastica, the actual Latin term which Hieronymi Mercuriale (Girolamo Mercurialis) used for personal close-combat skills was belli peritiam,

which translates roughly to “war skill” or “military skill”, not

literally martial arts as has been asserted. Mercuriale then made

reference to those “modern teachers“ who offer “exercises for

self-defence” or “what is commonly called fencing”. (Nutton, p. 347).

Also noteworthy is how

within the 1745 edition of, Teutsch-Englisches Lexicon, by Christian Ludwig, the term Kriegkunste

is translated directly as “martial arts”. This is consistent with

Germanic fighting methods from Medieval and Renaissance instructional

literature being themselves frequently described as the Kunst de Fechten,

or the Art of Fighting. However, by this time Ludwig associated it

more with military science rather than the old self-defense skills.

(Ludwig,

p.1087). Similarly, a 1601 English translation by Philemon Holland of

Pliny the Elder’s history of the world has him noting the Phoenicians as

being high reputed for their “martial skill”. But several 19th

editions then incorrectly translated the same phrase as “martial art.”

It

can also be noted that there was no equivalence between how “art of war”

and martial art were employed. There are few English instances starting

in the 16th century to the “art of war” or “arte of warrfare” and

little to none for “arts of war” or “war arts”. The phrase “art of

war” strictly referenced military science, such as Machiavelli’s, Arte Della Guerra, of 1529, or William Garrard’s 1591, The Art of Warre. Beeing the Onely Rare Booke of Myllitarie Profession. Both of which are on military methods not self-defence skills.

Martial, Martial, Martial

By the 15th century, describing something as martial was a

fairly common means to denote an exceptional or noteworthy achievement

displaying combat mastery or expertise in actions of war. Among its

definitions it could also mean a display of skillfulness or valorous

ability as well as a surprising move. In other words, a fighting

technique or fighting prowess. In description of noble fighting men,

martial feats was essentially used synonymous with the terms feats of

arms or deeds of arms —in the sense of specific incidents or occasions

of valorous personal combat. In John Lydgate’s 1425 translation of Troyyes Book,

it appears that “marcialle feates” was the accepted term used to refer

to a person or group having skill in fighting (what was frequently

termed prowess) as in “a goodly feate of armes.” His 1439, Fall of Princes (Bodleian MS 263) refers to “marcial high

prowess”.

An assortment of "martialisms" were commonplace. Without digressing into the morphology of the term (or its

modern hyphenated use —as in “martial-arts”), a range of martial terms

were employed in Renaissance era English texts on military knowledge and

skill in arms. These included: Martiall play, martiall prowess,

martiall-exercise, martial discipline, martyall affayres martial

occupation, martial field, martial force, martial men, martial armes,

and martiality. This is in addition to: martial actes, martial pastimes,

martial knyghthood, martial virtues, and “use of martiall weapons &

practises”, etc. As early as Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde of c.1374, we find “tourney marcial” and “assautis marcial”. Shakespeare’s, The Second Part of Henry the Fourth, from 1600, even contains the lines: “with arts and martial exercises” (Scene V, Act I). An assortment of "martialisms" were commonplace. Without digressing into the morphology of the term (or its

modern hyphenated use —as in “martial-arts”), a range of martial terms

were employed in Renaissance era English texts on military knowledge and

skill in arms. These included: Martiall play, martiall prowess,

martiall-exercise, martial discipline, martyall affayres martial

occupation, martial field, martial force, martial men, martial armes,

and martiality. This is in addition to: martial actes, martial pastimes,

martial knyghthood, martial virtues, and “use of martiall weapons &

practises”, etc. As early as Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde of c.1374, we find “tourney marcial” and “assautis marcial”. Shakespeare’s, The Second Part of Henry the Fourth, from 1600, even contains the lines: “with arts and martial exercises” (Scene V, Act I).

The military writer and humanist educator, Jacopo Porcia, in his

military treatise from the 1470s (translated into English by Peter

Betham in 1544 as, The Preceptes of Warre), advised of the need

“for young men in their youth to practyse martiall feates” (section

111). Though the term “feats” was often used to describe remarkable

deeds and actions of extraordinary courage or chivalric skill, in this

instance, Porcia was referring simply to training in personal fighting

skills.

Published works on the arte militarie, or what would later be considered military science (militaris scientiam),

were common place starting in the 1500s and were a separate category

from those addressing individual fighting needs (Thomas Styward even

entitled his 1581 military tract, The Pathwaie to Martial Discipline.). They were focused

instead on theories of war and soldiering. Various terms and phrases

such as “actes marcyall” and “actes marcyable” or “marcyall actes” can

be found as synonymous with the art militaris. Thus, there was a distinction between the ars martialis and the disciplina militaris.

This occurred even as “the martial art” could be defined as either

skills for war or skills for self-defence —as the two were obviously

synergistic. Similarly, the Master Franscesco Alfieri’s, La Spadone, published in Padua in 1640, refers in its opening line to the subject of fencing as, dell’ arte Militia —literally “the military art”. Several more examples like this could be pointed out.

The 1595 treatise on the rapier by Maestro Vincentio Saviolo, His Practise in Two Books,

opens with “this simple Discourse, of managing weapons, and dealing in

honorable Quarrels (which I esteem an Introduction to Martiall

affayres)”. Interestingly enough, in the epistle of his 1598 treatise,

the English master George Silver had directed his self-defence

teachings as being “fit for Marshall men” as well as expressing his

willingness to prove his skills fit for the “martial censure” of other

fencers. In the former he was referring to military leaders, and in the

latter, specifically to winning mock-combat bouts or sparring. The famed

15th century knight and condottiere, Sir John Hawkwood, was himself

described in one history from 1660 as “an exact master of Martial

affairs” (Winstanley, p. 90) By 1693, in Some Thoughts Concerning Education,

the philosopher John Locke himself followed tradition when he

essentially equated “martial skill or prowess” specifically to fencing

and dueling.

As late as 1696 in The Famous History of the Seven Champions of Christendom, a description of knights in battle states: “At the signal of the Trumpets sounding they set spurs to their Horses, encounter∣ing

each other with such well guided valour and Courage, as showed them

each to be a Master of Martial Prowess.” One commanding lord is then

described thusly: “Accordingly be bestirred himself in Mustring up of

his Men, shewing them how to handle their Weapons, and to use them to

the best advantage, also how to gain ground in fight, and when to

retreat, with other things belonging to Martial Discipline.” (Johnson,

p.105 & 19) Then, in a 1697 poem about King Arthur himself, Sir

Richard Blackmore described how: “His Camp the only School of War was

thought, Which all young Hero’s for instruction sought, for none had

Martial Art to such Perfection brought.” (Blackmore, p.23)

We may wonder about the synonymous and more general term,

“fighting art” in English. This is, however, even rarer and when it does

appear by 1900 it is almost always in relation to either boxing or

modern military theory. To consider just a few examples: An 1885 source

noted the recreational and sportive side of “the Fighting arts in

self-defence” referring to both unarmed and armed “fighting arts” and

“fighting sports.”(Dewey, p.7) One 1887 source covering English

composition and rhetoric employed it in regard to the military

profession being “the completed embodiment of the fighting art.” (Bain,

p. 156) An 1899 history of the early 16th century peasants war in

Germany stated: “knights, well-armed and equipped, and experienced in

the fighting art” (Bax, p.151) We may wonder about the synonymous and more general term,

“fighting art” in English. This is, however, even rarer and when it does

appear by 1900 it is almost always in relation to either boxing or

modern military theory. To consider just a few examples: An 1885 source

noted the recreational and sportive side of “the Fighting arts in

self-defence” referring to both unarmed and armed “fighting arts” and

“fighting sports.”(Dewey, p.7) One 1887 source covering English

composition and rhetoric employed it in regard to the military

profession being “the completed embodiment of the fighting art.” (Bain,

p. 156) An 1899 history of the early 16th century peasants war in

Germany stated: “knights, well-armed and equipped, and experienced in

the fighting art” (Bax, p.151)

So

then, what are we to make of historical use of “martial” such in as the

following from Leonardo Bruni’s work on Florentine chivalry, De militia,

from c.1420: “Braccio was a great man. He was considered a leading

exponent of the military art. He was noted for his great martial ability

and wise judgement.” (Bruni, p.363)? Are we to somehow believe

such statements merely referred to generic battlefield acumen and not

intentional to skill in the well-documented self-defence systems in

which we know fighting men trained? The intentional meaning of the word

in such instances is now obvious: they mean skilled in the “art

martial”.

Modern Meanings and Past Leanings

Despite there being near countless books and periodicals

offering dozens of definitions for it, until now it has been nearly

impossible to encounter any exploration of the actual historical origins

and usage of the familiar term “martial arts”. For decades the very

idea of martial arts has been defined as meaning the traditional

self-defense styles of East Asia and the Pacific Rim and those modern

fighting methods derived from them.

Search through virtually any encyclopedia, dictionary,

chronicle, instructional manual or mainstream news story on the subject

prior to the 2010s and the evidence is overwhelming for it as

specifically (and almost exclusively) referring to Asian self-defense

methods. From the 1960s, if not earlier, and continuing throughout the

early 2000s, it was commonplace to find literature on “the” martial arts

defined and identified only as “Eastern”, “Asian”, or even “Oriental”.

Indeed, use of this English phrase is so commonplace today that book

after book and article after article —whether on history or practice of

the subject— uses the term in this popular manner without a second

thought. (Yet, the prefix "Eastern" or "Asian" does not appear associated with the term until the mid-20th century.)

There are astonishingly few exceptions within any general references to this prejudice. For example: The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language

(Fourth Edition. 2000) defined martial art as: Noun: “Any of several

Asian arts of combat or self-defense, such as aikido, karate, judo, or

tae kwon do, usually practiced as sport. Often used in the plural.” Meanwhile, The Columbia Encyclopedia (Sixth Edition. 2000) states:

“various forms of self-defense, usually weapon less, based on techniques

developed in ancient China, India, and Tibet.” Even worse, from the Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary 2006 we find:

“martial art – a sport that is a traditional Japanese or Chinese form

of fighting or defending yourself. Kung fu and karate are martial arts.”

Online sources offering the origins of words, phrases and idioms are

also just as inaccurate. Numerous books with titles such as “World of

Martial Arts” or “Martial Arts of the World” in reality cover only the

histories of modern and traditional Asian styles.

As of this writing in 2025, the venerated Oxford English Dictionary

still incorrectly lists the earliest use of the term in English as

1678. And yet, it also offers the origin of its popular meaning as

merely being from Takenobu Yoshitarō’s, Japanese-English Dictionary, of 1920 which translated Bugei

as: “military arts (accomplishments); feats of arms; martial arts.” Takenobu’s 1887 edition of The Japan Year Book,

however, included what is probably the term’s first use in reference to

Japanese systems when noting the “relegation during the feudal period

of literature to position entirely secondary to martial arts” (Takenobu,

p.219) Yet, when describing Japanese culture and society in his

1904 book, Bushido, the Soul of Japan, An Exposition of Japanese Thought, author Inazo Nitobe employed the terms, martial traits, martial virtues, and martial prowess, but not martial arts.

However,

though it has come in modern times to be almost

exclusively a synonym for Asian fighting arts, this view is finally

beginning to change, and with good reason. Indeed, with few exceptions

prior to the 1890s, there is scant evidence for its use in this regard. In this same period, the 1888, A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles,

collected by the Philological Society, included pages worth of in depth

etymological entries on the word “martial” along with its associated

semantic network. Yet the work completely overlooked the variant

“martial art.”

The term certainly did not even make it into the 1913 edition of

Webster’s dictionary. The Oxford American Dictionary also

incorrectly offers a reference date of only 1783 with the origin as

being: “late Middle English from Old French, or from Latin martialis,

from Mars, Mart.” Definitions aside, none of these address the actual

original and true history of the term —nor place the martial arts of the

Renaissance in its proper context.

The earliest evidence so far for its use specifically to refer to a

practitioner of Asian fighting arts appears to not be until 1874 in The

Chinese reader's manual, referring to an 11th century royal who was

“distinguished no less by skill in the martial arts than by his profound

scholarship.” (Mayers, p.234) Though it makes several references to

martial prowess, martial skill, and martial abilities among nobility, it

curiously included only a single entry noting the term. This use

is therefore no different and no less commonplace than how the term had

been used throughout most the prior centuries when describing someone

possessing both military know-how and personal fighting skill. Only a handful of similar examples can be found among published

works from the 1890s that use the term to describe Japanese fighting

traditions. As well, the Dai Nippon Butoku Kai

or “Greater Japan Martial Virtue Society” was established in 1895,

although later it was frequently translated as if titled “The Japanese

Martial Arts Society”.

The term is noticeably missing in 19th century reports and

accounts of fighting disciplines in Japan and China, because for the

most part it was already forgotten or redefined in the West. It had

either been discarded in favor of “martial science” and “military arts”

or employed as a synonym for either. For example: An article on national

character from 1832 stated: “…the martial arts and valour are those by

which a Swiss the most hopes to promote.” (Chenevix, p. 315) From The New York Herald

in 1856, “The company was dressed partly in military and partly in

civilian dress, and evidently has not been much exercised in martial

arts of late.” From the Worcester Daily Spy in 1866, “The military lines of writing, sometimes as strategic and puzzling as any lover of the martial art could wish…”. An 1879 book of The Centennial Celebrations of the State of New York

described Britain as “an old and powerful government…which through

hundreds of years had been trained in martial arts.” (p.340)

An 1886

Congressional declaration honoring the noted Civil War general, Winfield

Scott Hancock, stated of him: “Bred in all the learning of the martial

art, practiced in its exercises, in stature, port and speech, the

soldier and the gentleman in lustrous perfection.“ (The Hickman Courier, June). And an 1898 Thanksgiving sermon in, The Florence Daily Tribune, by one Rev. C. A. Berger, declared how “the martial arts in army and navy constitute a nation blessed…” while The Canton Times

in a 1902 article described the historical Scottish Highland Campbell

clan as being, among other things, “masters” in “the martial science“.

Until Bruce Lee started to popularize the term as a

generic catch-all term for any self-defence method in general

(ostensibly avoiding defining the craft along national or ethnic lines)

it surprisingly does not even appear in the titles of books or articles

on the subject before the 1960s. Nor was the phrase ever used by F. J.

Norman in one of the earliest Western books on the subject, his

influential 1905, The Fighting Man of Japan. It also appears only once in all of E. J. Harrison's influential 1913 book “The Fighting Spirit of Japan.”

In fact, before 1900 it appears only intermittently even in published

material on the subject translated by Japanese nationals. Even in their

highly influential work published in 1969 under the title Asian Fighting Arts, the pioneering researchers of the subject, Donn Draeger and R.W. Smith, only used the term “martial art” twice

in some 200 pages of material. But starting in 1980, later editions

incorporated the term liberally and even re-titled the work that way.

The phenomenon of the term's absence in reference to

traditional Asian fighting arts until the late 19th century —whether by

native English speaking or native Asian translators— as well as the

phenomenon of its resurgence in the early 20th century, is beyond the

scope of this article (but it is covered at length in detail in the

larger paper). Suffice it to note that entries cannot be found for the term

within modern English language encyclopedias or dictionaries before the

1950s.

Where Are the Martial Artists?

All of this of course begs an obvious question: What about

the associated term “martial artist”? It certainly doesn’t appear in

the corpus of Renaissance fight book literature. Oddly enough, it seems

to have had a limited and later origin as it appears in the 19th century

as a rare label usually describing characteristics of soldiers and

warriors.

It’s safe to say that no one mainstreamed the popular use

of the term martial artist to specifically refer to a practitioner of a

close combat discipline than did Bruce Lee starting in the early 1960s.

Indeed, there’s little evidence that anyone else was actively using the

term in general parlance before his rise to fame —a fact revealed by

surveying books and periodicals on Asian self-defence methods (typically

judo, jujitsu, and karate) in the first half of the 20th century. It’s safe to say that no one mainstreamed the popular use

of the term martial artist to specifically refer to a practitioner of a

close combat discipline than did Bruce Lee starting in the early 1960s.

Indeed, there’s little evidence that anyone else was actively using the

term in general parlance before his rise to fame —a fact revealed by

surveying books and periodicals on Asian self-defence methods (typically

judo, jujitsu, and karate) in the first half of the 20th century.

Available evidence indicates that the expression was only

intermittently applied in the final decades of the 1800s —and

even then was also still being used to described historical military

figures. For example, From Saint Paul’s, Vol. 10, 1872, we find a

note on how Tsarevich Demetrius Ivanovitch in the early 17th century

was “proficient in all martial arts” (p.265). A 1903 London magazine, Truth,

described one, “Mr. Caton Woodville” as “a martial artist”. Yet

Woodville was not a practitioner of any fighting method but only a

veteran marksman and accomplished big-game hunter. (Truth, Volume 52, p.485, 1903.)

Thus, referring to an individual as being a “martial

artist” appears to be a fairly modern phenomenon and the expression is

not all that old. For that matter, in his assorted small-sword fencing

works from the 1690s, the Scotts master, Sir William Hope, was among the

very first ever to regularly refer to practitioners of the science of

defence as being “artists” (in contrast to the untrained or

“ignorants”).

Are We Not Martialists?

An overlooked historical term for a trained fighting man was a martialist.

Martialist appears in numerous instances in both Latin and English

tracts from the 15th to 17th centuries. It can readily be found in

several early 16th and late 17th century works associated with warriors,

military professionals, and soldiers. It could also mean a

“fray-maker” (essentially, a street fighter) but was not generally used

in the derogatory for someone prone to violence or war (as in the

unflattering term, militarist). In the 14th century it had

been used to refer to a person born under the astrological influence of

Mars. Typically, a martialist” (or “martialiste”) generally referred to a

fighting

man well-trained in combat skills. Quite often it translated to meaning

a general skillfulness in waging war and commanding troops in battle

—which would inherently include an overall understanding of wielding

arms. But a “martialist in armes” is not an uncommon phrase to find in

16th and 17th century writings on dueling as well as military science.

Within a circa 1255 interrogation of Albigensian heretics

before the inquisitor, Brother Bernard of Caux, we find listed among the

witnesses of priests and clerks a certain magister martialis or “martial master”. (Samaran, Manuscrits datés,

v. 6, p. 415). Guillaume Budé referenced the phrase “martialist steps”

in 1530, while it appears in Philippi Boraldi’s 1512 edition of

Apuleius’s 1st century work, Asininus Aureus as: Marcialist in omnibus

uacerra quod conclauibus (“A martialist in all things that he did” Fol.

XXVv).

To defer to the noted linguist and lexicographer, John Florio, from his 1598 English-Italian dictionary, A Worlde of Wordes, he offers both, martialle as “a martiall man, a man of Mars”, and martialista (from the Latin, marcialis, of or belonging to Mars) as “a martialist of the nature of Mars” (Florio, p.217). John Lydgate’s 1513, The hystorye, sege and dystruccyon of Troye,

described Achilles himself by the following: “In all that longeth to

manhode dare I sayne, He besyeth ever and therto is so fayne, To haunte

his body in playes marcyall, Thorugh excercise to exclude southe at all,

After the doctryne of vigecius, Thus is he bothe manfull and vertuous”.

In modern English this would essentially be: “In all that pertains to

manhood, I dare say, he always busies himself and is so eager to train

his body in martial exercises, through practice to completely exclude

laziness, following the teachings of Vegetius, thus he is both

courageous and virtuous. Those “teachings of Vegetius”, of course, were

focused on the Roman military recruit twice a day practicing cuts and

parries at the post for hours with his wooden sword. To defer to the noted linguist and lexicographer, John Florio, from his 1598 English-Italian dictionary, A Worlde of Wordes, he offers both, martialle as “a martiall man, a man of Mars”, and martialista (from the Latin, marcialis, of or belonging to Mars) as “a martialist of the nature of Mars” (Florio, p.217). John Lydgate’s 1513, The hystorye, sege and dystruccyon of Troye,

described Achilles himself by the following: “In all that longeth to

manhode dare I sayne, He besyeth ever and therto is so fayne, To haunte

his body in playes marcyall, Thorugh excercise to exclude southe at all,

After the doctryne of vigecius, Thus is he bothe manfull and vertuous”.

In modern English this would essentially be: “In all that pertains to

manhood, I dare say, he always busies himself and is so eager to train

his body in martial exercises, through practice to completely exclude

laziness, following the teachings of Vegetius, thus he is both

courageous and virtuous. Those “teachings of Vegetius”, of course, were

focused on the Roman military recruit twice a day practicing cuts and

parries at the post for hours with his wooden sword.

A

statement included in the 1594 English translation of Giacomo Di

Grassi’s major 1570 work, His True Art of Defence, declared it one “most

of the marshal mynded gentlemen of England cannot but commend”. A 1576 translation of the

history of Aelian even again refers to Achilles as “valiant and so

conquerous a Martialist” and Geoffrey Gates’ 1579, The Defence of Militarie Profession,

described Julius Caesar as “the best renowned martialist of the world”

and in 1584, Barnaby Rich employed it in his tome by citing “the company

of…our Martialist Don Pirro de Feragosa”. But, in his 1583, The Anatomies of Abuses,

the moralist Phillip Stubbes remarked that for “so stout a martialist”

an ordinary plain sword or rapier was just as functional as overly

decorated ones “to have any dueling with them”. (Stubbes, p.64)

Similarly, the 1608 poetic work, Merry Devil of Edmonton, reads: “Did we not last night find two St. George’s here. Yes, Knights, this martialist was one of them.”

The 1591, “Discourses on Warre and Single Combat” (a translation of Bertrand de Loque’s 1589, Deux Traitéz: l'un de la guerre, l'autre du duel)

refuting the morality for the Christian to engage in dueling, also

referred to “martialists” as being essential military men and swordsmen. Additionaly, Coryat’s Crudities of

1611 described Carolus Martellus as “the most fortunate and valiant

Martialist that was then in all the world”, while a 1627 English

biography of Aloysisus Gonzaga by Virgilio Cepari described him as

“being a Martialist who had undergone many martiall affayres”. From the

1603, Vertues Common-wealth, by H. Crosse, we find: “A true Martialist he is indeed, that by strong hand labours to suppresse his rebellious lusts.”

A 1612 poem by George Wither, even reads: “For whil’st

that though wert armed within my list, he dared not meet thee like a

Martialist. Alas, who now shall grace my turnament. Or honor me with

deeds of chivalrie?” Similarly, in The Two Noble Kinsmen, a 1634

play attributed to William Shakespeare and John Fletcher derived from

Chaucer’s “The Knight’s Tale”, the title “martialist” is used

specifically to mean a knight or soldier. Donald Lipton’s 1642 military

treatise on use of the pike also referred to anyone with an interest in

the profession of war as a martialist. Later, in the 1726, Universal Etymological English Dictionary, it was still defined as “a Warriour, a Man at Arms.” (N. Bailey. 3rd ed.)

By contrast, to distinguish how the older Art of Defence shifted from

being about all weapons and unarmed skills toward an almost exclusive

focus on the single small-sword and saber, we can note that the first

book in English with the word “fencing” in its actual title was not printed until 1687 (!).

A martialist then, can be essentially anyone who practices

martial arts or military disciplines, or someone skilled in or devoted

to study of combat or the art of war. Yet, the term martialist likely

fell out of favor as Western civilization moved from traditional warrior

skills (as reflecting the individual nature of Mars) towards those

conceived for modern militaries. It is easy enough to then imagine how

as such characteristics became more focused, so too the definition would

as well. But its meaning as someone professionally trained in fighting,

or who makes fighting their profession, is sensible. After all, we

don’t call someone a “musical artist” we just say they are a musician.

It would seem then that the associated term “martial artist”, defined in

its broadest and most popular sense, if not in use by the mid-16th

century, was almost on the tip of their tongues waiting for release,

though this was not to occur until the mid-20th century. Yet, one must

therefore ask: Is not calling those trained in the arts of Mars, "martialists", once again something reasonable? A martialist then, can be essentially anyone who practices

martial arts or military disciplines, or someone skilled in or devoted

to study of combat or the art of war. Yet, the term martialist likely

fell out of favor as Western civilization moved from traditional warrior

skills (as reflecting the individual nature of Mars) towards those

conceived for modern militaries. It is easy enough to then imagine how

as such characteristics became more focused, so too the definition would

as well. But its meaning as someone professionally trained in fighting,

or who makes fighting their profession, is sensible. After all, we

don’t call someone a “musical artist” we just say they are a musician.

It would seem then that the associated term “martial artist”, defined in

its broadest and most popular sense, if not in use by the mid-16th

century, was almost on the tip of their tongues waiting for release,

though this was not to occur until the mid-20th century. Yet, one must

therefore ask: Is not calling those trained in the arts of Mars, "martialists", once again something reasonable?

The Martial Art?

All of this only begins to scratch the surface of the

number of examples for the use of the term martial art in the 15th and

16th century and doesn’t yet begin to address the intriguing matter of

how these combat disciplines were viewed at the time as both science and

art. In its early incarnation the martial art —in the

singular— referred to individual fighting skills for battle or personal

combat. It then later became largely synonymous with the term military

art and military science. Not until the late of 19th century did martial arts begin once more to take on its original meaning but it did so for an entirely new reason.

I’m pleased to be able to present a preview of my just

some of my findings on this topic given that an article like this is

long overdue. A more exhaustive and formal research paper is being

prepared that covers the term’s use and evolution beyond the Renaissance

era. I expect it will serve as a primary reference for practitioners

and students of any kind of combative discipline but especially for

those within the historical fencing community who have reclaimed the

term over the past two decades. But one thing is for certain: Regardless

of its historical and modern application, in various forms the term

“martial art”, from the Arts of Mars, was once a name for systematic

fighting methods indigenous to Western Europe. I’m pleased to be able to present a preview of my just

some of my findings on this topic given that an article like this is

long overdue. A more exhaustive and formal research paper is being

prepared that covers the term’s use and evolution beyond the Renaissance

era. I expect it will serve as a primary reference for practitioners

and students of any kind of combative discipline but especially for

those within the historical fencing community who have reclaimed the

term over the past two decades. But one thing is for certain: Regardless

of its historical and modern application, in various forms the term

“martial art”, from the Arts of Mars, was once a name for systematic

fighting methods indigenous to Western Europe.

The use of the term martial art has a long and rich

legacy, in particular within English language prose and poetry. As the

evidence shows, it was common for a time to even refer in the singular

to “the martial art”. Though it would hardly be practical, it would be

perfectly reasonable for anyone now studying the “martial science” —as

recorded in Renaissance-era fight books— to declare that they practice “the martial art”. For are we not martialists?

The preceding is an excerpt from a larger academic

paper on the origin and historical use of the term martial arts and its

evolution in later centuries to modern times.

3-2025

—————————

*Despite there being near countless definitions for it, I

have never encountered any exploring the actual historical origins and

usage of the term martial arts. It is a curiosity how for about the last 75 years or so, it's been associated almost exclusively with Asian

fighting arts and not with any of their Western counterparts from whence

the term originates. For example, Egerton Castle, in his unprecedented 1885 tome Schools and Masters of Fence from the Middle Ages to the 18th Century,

did not once include the term “martial art” in describing the science

of defence and the art of fencing that he was examining in detail. Nor

did any of his

contemporaries documenting historical fencing literature, such as

Jacopo Gelli or Carl Tim. A work like Castle’s would not even be

produced again until the more limited approach taken by Arthur Wise in

his 1971 The History and Art of Personal Combat, which also

completely neglected to employ so obvious a term for its own subject of

inquiry. Much as with the authors of 18th and 19th century fencing

books, to them, all ancient, Medieval, Renaissance, or other armed

combat was just “fencing” and anything

unarmed was wrestling or boxing. Indeed, it wasn't until the early

1990s that the term martial art was finally being used in reference to

describing Medieval and Renaissance combat disciplines. At the time,

only a handful of individuals, myself included, were deliberately

calling them Western martial arts in published materials. This

culminated in Sydney Anglo’s seminal volume from 2000, The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe,

which quickly became the leading reference (as well as helped properly

lock in the broader

use of the term). The fairly modern term of “combatives” as as a noun

employed specifically about self-defence or martial arts —but not as an

adjective for participants in a battle or those prone to fighting— does

not seem more recent than 1906. It appears to not have become vernacular

in military circles until around the 1970s and did not pick up in

popularity until after 2001.

**Though I laugh now whenever I hear it claimed

that “the West had no martial arts”, I have also for some time now found

it amusing that in the late ‘90s and early 2000s there were those who

were bragging how they were “fencers“ and not “martial artists”. Then a

few years later, as more fight book translations became available and

even more unknown source works were being discovered, those very same

folk instantly began describing themselves as “martial artists” —as well

as changing the name of their assorted Medieval/classical/historical

fencing, dueling, stage-combat, swordplay clubs, and larping societies to

reflect the term.

|