|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

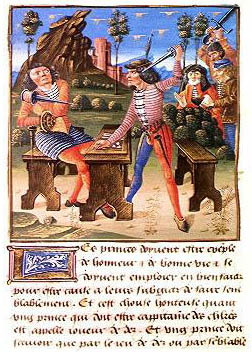

| One 13th century Codex shows young men engaged in sword and buckler play under the admiring gaze of two noble women. A 14th century painting of the capture of the knight Guy de Greville at Château d’Evreux in France shows his armored captor carrying a spear and wearing sword and buckler. A mid-14th century English Psalter portraying the Biblical combat between David and Goliath portrays Goliath (viewed as a knight) in contemporary plate armor with a sword and buckler. |

|

|

|

A realistic 14th century illustration showing Henry V meeting with his knights illustrates the well-armored men equipped with small studded bucklers over the hilts of wide-bladed swords worn on their hips (British Library MS Cotton Julius E IV). A similar 15th century French painting of the battle of Crécy (in 1348) depicts armored knights on foot fighting with sword and buckler and falchion and buckler. From 1469, an illuminated manuscript image by the Flemish artist, Lieven van Lathem, of a winged St. Michael fighting winged demons (J. P. H Getty museum, MS. 37, fol. 15V) similarly has him in plate armor with a short thrusting sword and small, hand-held iron shield. |

An

anonymous illuminated manuscript image of a battle between an angel

and a dragon from the c.1255 Dyson Perrins Apocalypse (J. P. H Getty

museum, MS. Ludwig III 1, fol. 20V) pictures the winged seraph wielding

a short sword and small, golden buckler.

An

anonymous illuminated manuscript image of a battle between an angel

and a dragon from the c.1255 Dyson Perrins Apocalypse (J. P. H Getty

museum, MS. Ludwig III 1, fol. 20V) pictures the winged seraph wielding

a short sword and small, golden buckler.

Along

with the use of longswords on foot the knights are also shown mounted

with short swords and even bows (yet nowhere in this or its related

series of paintings are any shields seen). Even St. George himself is

portrayed in 15th and 16th century paintings as a winged angel in golden

armor wielding a sword and buckler or a sword and buckler armed knight

in plate armor. A 1452 painting of the Last Judgment by Petrus Chritus

(in the Gemäldegaleie, Staatlide museen, Berlin), depicts

no less a figure than the archangel Gabriel fighting demons with a sword

and buckler while armored in full plate.

|

|

|

|

|

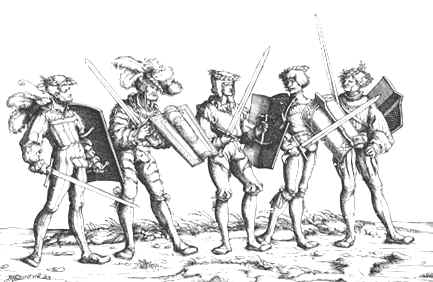

A colorful image of mid-15th century German knights exercising includes the activities of wrestling, staff fighting, stone lifting, and sword and buckler play. The Emperor Maximilian I is even depicted in full plate armor practicing sword and buckler in Der Freydal (c.1500). The Triumphzug of Maximilian I also shows his processional guards armed with buckler and long bladed close-hilt swords. | |

| Even into the 1500s, the sword and buckler continued to be used by knights as much as commoners. For example, an Aztec image of Cortez and his knights under siege in Tenochtitlán in 1520 actually reveals them in full plate armor with several armed with sword and buckler. Even the famous 1547 judicial duel between the courtiers Jarnac and Chatstaigneraie was itself fought with sword and buckler. | ||

Bucklers

were not only weapons for war; they were common tools for essential

fencing practice as well. As a training system, the sword and

buckler’s value lies in learning the coordination of two weapons,

of joint attack and defense, and of applying different ranges and specific

techniques of cut and thrust. The learning of timing, judgment,

and footwork are also conveyed by the practice.

Bucklers

were not only weapons for war; they were common tools for essential

fencing practice as well. As a training system, the sword and

buckler’s value lies in learning the coordination of two weapons,

of joint attack and defense, and of applying different ranges and specific

techniques of cut and thrust. The learning of timing, judgment,

and footwork are also conveyed by the practice.

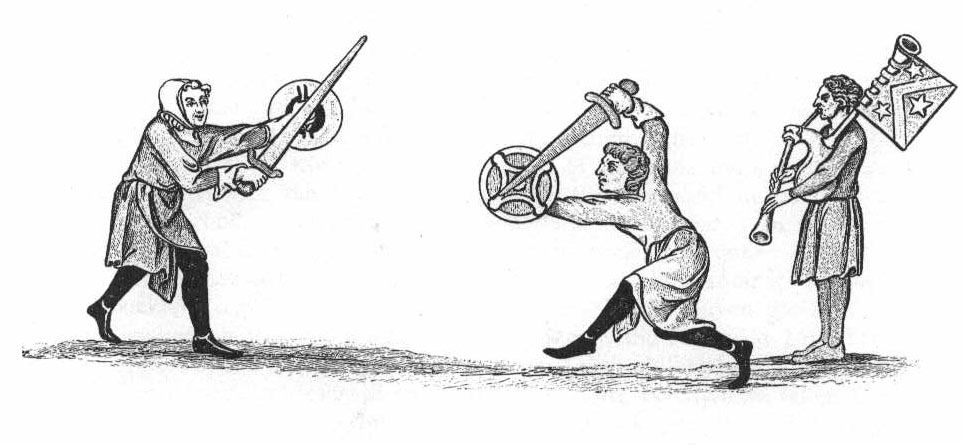

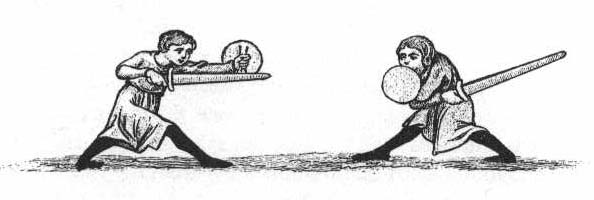

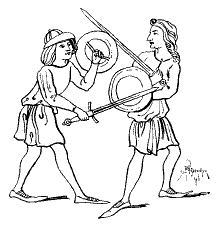

The

martial exercise of sword and buckler, first known as Eskirmye de

Bokyler, appears to have first become common in the 12th

century. Seen here are two images of the time (MS No. 14, E. iii.,

and MS No. 20. D. vi, and MS No. 14, E. iii., 13th century.). A late

12th century image of club and buckler fencing can even be

found on bronze cathedral door panels in Trani, Italy. About

c. 1178, William Fitzstephen described how in London “During the

holydays in summer the young men exercise themselves…fighting with

bucklers.” The famous I.33 manuscript seems to suggest it

as self-defense and martial exercise, at least by monks in Germany,

as early the 13th century.

The

martial exercise of sword and buckler, first known as Eskirmye de

Bokyler, appears to have first become common in the 12th

century. Seen here are two images of the time (MS No. 14, E. iii.,

and MS No. 20. D. vi, and MS No. 14, E. iii., 13th century.). A late

12th century image of club and buckler fencing can even be

found on bronze cathedral door panels in Trani, Italy. About

c. 1178, William Fitzstephen described how in London “During the

holydays in summer the young men exercise themselves…fighting with

bucklers.” The famous I.33 manuscript seems to suggest it

as self-defense and martial exercise, at least by monks in Germany,

as early the 13th century.

|

|

|

Illustrations

of sword-and-buckler contests are depicted in manuscript miniatures

from the early and mid 1300s.[1] The term “foyle”

(i.e., practice weapon) is even mentioned in reference to sword and

buckler fencing as early as the 1200s. (Ashdown, p. 316-317).

William Caxton’s translation of the Catholicon Anglicum,

an early English-Latin dictionary from c. 1483, even related the art

of fencing itself directly to the use of sword and buckler: “a

Bucler plaer, gladiator; a Bucler playnge, gladiatura.

Swerde & yebucler (bukiller) playnge, gladiatura.”

[2] A 15th century Venetian image depicts

figures remarkably similiar to German fighters of more than two centuries

earlier. A Spanish Bible from c1320 depicts an odd assortment of margin

illuminations featuring half-animal half-man figures posing or fighting

with various weapons and a considerable portion of them featuring short

swords with round bucklers.

Illustrations

of sword-and-buckler contests are depicted in manuscript miniatures

from the early and mid 1300s.[1] The term “foyle”

(i.e., practice weapon) is even mentioned in reference to sword and

buckler fencing as early as the 1200s. (Ashdown, p. 316-317).

William Caxton’s translation of the Catholicon Anglicum,

an early English-Latin dictionary from c. 1483, even related the art

of fencing itself directly to the use of sword and buckler: “a

Bucler plaer, gladiator; a Bucler playnge, gladiatura.

Swerde & yebucler (bukiller) playnge, gladiatura.”

[2] A 15th century Venetian image depicts

figures remarkably similiar to German fighters of more than two centuries

earlier. A Spanish Bible from c1320 depicts an odd assortment of margin

illuminations featuring half-animal half-man figures posing or fighting

with various weapons and a considerable portion of them featuring short

swords with round bucklers.

There

are accounts of sword and buckler practice having been a pastime enjoyed

as a form of martial sport by commoners in both England and Northern

Italy from the 1200s -1400s and it was also evidently a popular

pastime in Germany. We also know “sword and buckler fighting

remained a popular spectator sport, particularly in urban areas, well

into the 14th century.” (Nicolle, Medieval Warfare, p. 252).

The system was also common in judicial combats as one 15th

century statement relates that duels among commoners in France were

“only fought with the buckler and baton...”

(Gilchrist, p. 32) and in 1455 two commoners in Valenciennes

were taught the use of the club and buckler for a judicial combat.

In a tale of Robin Hood from Anthony Munday’s, The Downfall of Robert, Earle of Huntington (c.1598) the Medieval sword and buckler tradition is described as both a trusted means of martial contest and self-defense (lines 2560-2570):

Prince John: “What meane this groome and lozell Frier, So strictly matters to inquire? Had I a sword and buckler here. You should aby these questions deare.”

Frier: “Saist thou me so lad? Lend him thine. For in this bush here lyeth mine. Now will I try this newcome guest.”

Scathlock: “I am his first man, Frier Tuck, And if I faile and have no lucke, Then thou with him shalt have a plucke.”

Frier: “Be it so Scathlock. Holde thee lad, No better weapons can be had. The dewe doth them a little rust. But heare ye, they are tooles of trust.”

As

a common practice at this time sword and buckler fencing could easily

turn into serious brawling. Aylward refers to how in London during

the late 1200s the city was pestered by bands of young fellows parading

the streets after dark clashing their swords against their bucklers

and harassing peaceable citizens to do combat. (Aylward, p. 8).

Even in 1452 an English petition complained of, the “gret multitude

of mysrewled people” assaulting and murdering others “wyth

swerd, bokeler, and dagareis”.[3]

It is known that English laws from as early as c. 1180 banned schools

of fence within the city of London and Edward I, in the Statuta Civitatis

London of 1286, ordered fencing schools teaching Eskirmer au

Buckler (or eskirmye de bokyler) banned from the City of

London –ostensibly to control villainy and prevent criminal mischief

associated with such activities.[4]

These edicts against the practice were aimed not specifically at sword

and buckler fencing itself, so much as the whole teaching of martial

arts to a civilian population. A skillful populace after all might

be prone to using their arms in resistance against the civil authority.

The restrictions were not at all intended to discourage fighting arts

in general in England, but to prevent street-fighting among young “sword-men”

bravados and to prevent any training in arms of common thugs and ruffians

who did not have the desired social conscience to responsibly bear arms

safely in good society.

As

a common practice at this time sword and buckler fencing could easily

turn into serious brawling. Aylward refers to how in London during

the late 1200s the city was pestered by bands of young fellows parading

the streets after dark clashing their swords against their bucklers

and harassing peaceable citizens to do combat. (Aylward, p. 8).

Even in 1452 an English petition complained of, the “gret multitude

of mysrewled people” assaulting and murdering others “wyth

swerd, bokeler, and dagareis”.[3]

It is known that English laws from as early as c. 1180 banned schools

of fence within the city of London and Edward I, in the Statuta Civitatis

London of 1286, ordered fencing schools teaching Eskirmer au

Buckler (or eskirmye de bokyler) banned from the City of

London –ostensibly to control villainy and prevent criminal mischief

associated with such activities.[4]

These edicts against the practice were aimed not specifically at sword

and buckler fencing itself, so much as the whole teaching of martial

arts to a civilian population. A skillful populace after all might

be prone to using their arms in resistance against the civil authority.

The restrictions were not at all intended to discourage fighting arts

in general in England, but to prevent street-fighting among young “sword-men”

bravados and to prevent any training in arms of common thugs and ruffians

who did not have the desired social conscience to responsibly bear arms

safely in good society.

“In

Bergamo in 1179 one particular training exercise is referred to as a

‘battle with small shields’ which suggests light infantry

training: this became more common during the 13th century.

All classes took part in what became a form of public entertainment.

Wooden weapons were used in these pugne or ‘fights’:

we also know that judges imposed heavy fines on anybody caught using

iron weapons. By the 14th century such exercises often

degenerated into brawls in which only youngsters took part: this in

itself reflected the decline of the old urban militias.”

(Nicolle, Italian Miltiaman, p. 31). Urban militias, the

main forces at the disposition of Medieval Italian cities, tended to

consist of conscripted freemen or mercenaries and they were expected

to be proficient in the use of weapons (particularly the scuderi

or “small shield” infantry). (Nicolle, Italian Miltiaman,

p. 15 & 16). These Medieval urban militias declined by the late

15th century and were replaced by sword and buckler foot

soldiers.

“In

Bergamo in 1179 one particular training exercise is referred to as a

‘battle with small shields’ which suggests light infantry

training: this became more common during the 13th century.

All classes took part in what became a form of public entertainment.

Wooden weapons were used in these pugne or ‘fights’:

we also know that judges imposed heavy fines on anybody caught using

iron weapons. By the 14th century such exercises often

degenerated into brawls in which only youngsters took part: this in

itself reflected the decline of the old urban militias.”

(Nicolle, Italian Miltiaman, p. 31). Urban militias, the

main forces at the disposition of Medieval Italian cities, tended to

consist of conscripted freemen or mercenaries and they were expected

to be proficient in the use of weapons (particularly the scuderi

or “small shield” infantry). (Nicolle, Italian Miltiaman,

p. 15 & 16). These Medieval urban militias declined by the late

15th century and were replaced by sword and buckler foot

soldiers.

By

the 1500s the buckler continued to be recognized as a necessary tool

of war as well as a foundational system for learning self-defense.

Costume books from the 16th century also depict plebian urban youths

around Europe wearing swords and bucklers. (Anglo, Martial Arts,

p. 324, Note 111). The Bolognese master Achille Marozzo, in his

famous 1536 fencing treatise, Opera Nova, made it clear the Spada

e Brochiero (sword and buckler) as a foundational weapon was suited

to both war and common self-defense. Marozzo even stated that

to save time in describing the various guards for weapons that he would

explain them only in terns of the single sword or the sword and buckler

–implying ostensibly that the sword and buckler was a foundational

tool for learning. He also depicted a unique square buckler (Spada

e Targe) with convex curved sides to aid in deflecting.

By

the 1500s the buckler continued to be recognized as a necessary tool

of war as well as a foundational system for learning self-defense.

Costume books from the 16th century also depict plebian urban youths

around Europe wearing swords and bucklers. (Anglo, Martial Arts,

p. 324, Note 111). The Bolognese master Achille Marozzo, in his

famous 1536 fencing treatise, Opera Nova, made it clear the Spada

e Brochiero (sword and buckler) as a foundational weapon was suited

to both war and common self-defense. Marozzo even stated that

to save time in describing the various guards for weapons that he would

explain them only in terns of the single sword or the sword and buckler

–implying ostensibly that the sword and buckler was a foundational

tool for learning. He also depicted a unique square buckler (Spada

e Targe) with convex curved sides to aid in deflecting.

The buckler’s

popularity at this time was still primarily due to its continued utility

on the battlefield. In 1558 the Frenchman Stephen Perlin wrote

of England, “it is to be noted the servants carry pointed bucklers,

even those of bishops and prelates…The husbandmen, when they till

the ground, leave their bucklers and swords…so that in this land

every body bears arms”. The 1631 edition of John Stow’s, Annales, mentioned how in the

mid 1500s “every serving-man, from the base to the best, carried

a Buckler at his backe, which hung by the hilt or pommel of his Sword,

which hung before him.” Stow also noted that every haberdasher

at the time then sold bucklers. (John Stow, Annales, p. 1024).[5]

The buckler’s

popularity at this time was still primarily due to its continued utility

on the battlefield. In 1558 the Frenchman Stephen Perlin wrote

of England, “it is to be noted the servants carry pointed bucklers,

even those of bishops and prelates…The husbandmen, when they till

the ground, leave their bucklers and swords…so that in this land

every body bears arms”. The 1631 edition of John Stow’s, Annales, mentioned how in the

mid 1500s “every serving-man, from the base to the best, carried

a Buckler at his backe, which hung by the hilt or pommel of his Sword,

which hung before him.” Stow also noted that every haberdasher

at the time then sold bucklers. (John Stow, Annales, p. 1024).[5]

In

an engraving of an ideal army encampment from Leonhard Fronsperger’s

1565 treatise, the Book of War, one portion is marked for two

figures practicing with swords and bucklers. (See Arnold, Renaissance

at War, p. 56). English military author Gerat Berry in his

1634, A Discourse of Military Discipline, wrote of the value

of training with the sword & buckler for war stating:

In

an engraving of an ideal army encampment from Leonhard Fronsperger’s

1565 treatise, the Book of War, one portion is marked for two

figures practicing with swords and bucklers. (See Arnold, Renaissance

at War, p. 56). English military author Gerat Berry in his

1634, A Discourse of Military Discipline, wrote of the value

of training with the sword & buckler for war stating:

Let him [the common soldier] practice him selfe in eache sorte of weapon, to imitate as neere as possible the Janisaros Turcos [Turkish Janissaries], who were moste experte in armes trough their continuall exercise; And let him frequent the sworde and target, and specially I woulde wish our Irish to frequent the same for beinge more inclined to this sort of weapon more than any other nation, and besides that of all nationes none are more fitt for the same, nor more resolute. This weapon is of greate imporrance in many occationes, and specially when men close together, or to vive or recnoledge any narowe or straight pasadge or place as trenches, fortes, batteries, assaultes, encamisada, and for other purposes in warr; and specially a boute the cullores or to defende or offende in any narrowe place.[6]

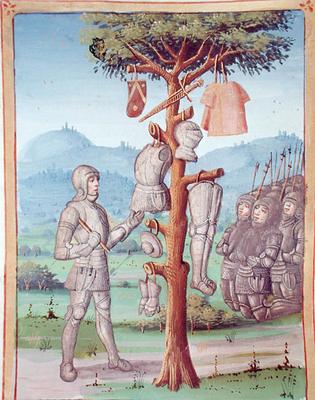

A

late 15th century illuminated image by Jardin de Vertueuse (J. P. H

Getty museum, MS. Ludwig XV 8, fol. 41) on the life of Alexander presents

another example solider in plate mail with a short sword and small buckler

on his right hip.

A

late 15th century illuminated image by Jardin de Vertueuse (J. P. H

Getty museum, MS. Ludwig XV 8, fol. 41) on the life of Alexander presents

another example solider in plate mail with a short sword and small buckler

on his right hip.

While it may be considered that the sword and buckler also served a secondary role as a training tool for learning to use larger shields, in the same way that a short sword or short staff teaches the use of a longer one, there is no real evidence for this. It is reasonable that knowing how to fight with a smaller, more maneuverable, hand-held shield would be useful in employing larger ones but there are still significant differences in how each is handled and what they can do. Certainly the volume of historical material on fighting with the buckler by far outweighs any on the employment of larger shields. This alone suggests that the sword and buckler was its own independent fencing skill and not viewed as a training tool for something else.

|

|

|

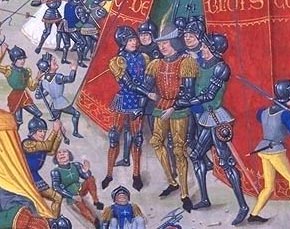

A

15th painting in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France depicting

the English and Scots fighting at the 1388 battle of Otterburn from

Froissart's Chronicles (BNF FR 2645), includes heavily armored troops

using a variety of oval bucklers with their short swords. Another similar

painting depicting Charles of Blois being taken prisoner in 1347 (BNF

FR 2643) portrays one of his knightly captors wearing at his left thigh

a small colored buckler hanging upon his longsword. Over all, bucklers

outnumber larger arm-worn shields by a ratio of roughly 5 to 1 in such

14th and 15th century artwork.

A

15th painting in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France depicting

the English and Scots fighting at the 1388 battle of Otterburn from

Froissart's Chronicles (BNF FR 2645), includes heavily armored troops

using a variety of oval bucklers with their short swords. Another similar

painting depicting Charles of Blois being taken prisoner in 1347 (BNF

FR 2643) portrays one of his knightly captors wearing at his left thigh

a small colored buckler hanging upon his longsword. Over all, bucklers

outnumber larger arm-worn shields by a ratio of roughly 5 to 1 in such

14th and 15th century artwork.

|

[1] Hewitt, p. 317 as citing Roy. MSS. 14, E. iii. And 20, D. vi, as well as Hefner, Pt. Ii. Plate vii.

[2] Lyf of the noble and Crysten prynce, Charles the Grete translated from the French by William Caxton and printed by him 1485. Edt. Sidney J. H. Herrtage. Early English Text Society. Oxford University Press. London, New York, Toronto. 1880-1881. Derived from British Museum, press mark c. 10, b. 9. Reprinted (as one volume) 1967.

[3] Paston Letters and Papers of the Fifteenth Century, Paston family v. : facsims., map ; 24 cm. : Clarendon PressOxford 1971, p. 59.

[4] “Whereas it is customary for profligates to learn the art of fencing, who are thereby emboldened to commit the most unheard-of villainies, no such school shall be kept in the city for the future”. (Castle, p. 16-17). Interestingly, the edict notes that “most of the aforesaid villainies are committed by foreigners”.

[5] There has been some question as to the manner of wearing the buckler. Medieval illustrations show small bucklers worn face outward on the belt and over the hilt of the sword. No illustrations of outward facing bucklers being worn are known. The famous Wallace Collection in London has several bucklers of various sizes in its armory. Some of these have hooks on their center umbo and others have hooks on their rims. Some of the hooks face upward while others face down. Some of the hooks are very tight while others are much wider. If such hooks were commonly used to hang bucklers on the belt as has been suggested, then this could not possibly work either for those hooks facing upward or for the large wide hooks. Nor would it make sense for those hooks on the rims of the large bucklers for these small shields would be an encumbrance carried that way. Only small bucklers with medium sized hooks would permit them to be slung on the belt or even on the counter-bars of a close-hilt sword. Bucklers with both rim hooks and center spikes certainly could not be carried on the belt. However, on some bucklers these smaller hooks actually sit recessed in the center below the raised bars welded to the buckler’s face. These raised bars were specifically designed to help catch or trap the fine points of rapiers and hooks in this position must have served a similar purpose. Larger hooks and those facing upward on the rim would hardly be useful for this but might be useful for hanging lanterns at night.

[6] Gerat Berry. A Discourse of military discipline, devided into three boockes, declaringe the partes and sufficiencie ordained in a private souldier, and in each officer; servinge in the infantery, till the election and office of the captaine generall; and the last booke treatinge of fire-wourkes of rare executions by sea and lande, as alsoe of firtifications. Composed by captaine Gerat Barry, Irish at Bruxells, by the widowe of John Mommart, 1634, p. 9.

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||