The

Sword & Buckler The

Sword & Buckler

Tradition - Part 4

Conceptions and Misconceptions

The method of fighting with sword and buckler remained

consistent over time. It was not significantly different in the

1500s than it was in the late 1200s. There are no major differences

between the wards, strikes, or actions found in sword and buckler fencing

literature of these eras. There are of course distinctions between

using a lighter tapering blade of the 1500s compared to the earlier

wider swords designed more for cutting blows. A narrow cut-and-thrust

blade allows for greater use of agile thrusting and quick slices against

unarmored opponents. While a Medieval shearing sword, typically encountering

more armors and heavier weapons, generally needed to deliver more powerful

edge strikes. Still, the techniques of 16th century

sword and buckler fencing were not original, but dated back to the Middle

Ages.

Yet,

a myth of fencing history that has developed is that the sword and buckler

(particularly the English system) was by the mid 1500s an antiquated

and obsolete style of defence. This view became more entrenched in the

recent century. A common prejudice that can be found within modern

fencing, which often views 18th & 19th century methods

as “superior” rather than as a separate development of civilian

dueling and urban self-defence, is that sword buckler fighting was crude

and simplistic. Yet,

a myth of fencing history that has developed is that the sword and buckler

(particularly the English system) was by the mid 1500s an antiquated

and obsolete style of defence. This view became more entrenched in the

recent century. A common prejudice that can be found within modern

fencing, which often views 18th & 19th century methods

as “superior” rather than as a separate development of civilian

dueling and urban self-defence, is that sword buckler fighting was crude

and simplistic.

This prejudice is most evident in comments

such as that by the famous Victorian scholar of fencing, Egerton Castle, who referred to “relatively barbarous sword

and buckler” (Castle, p. 20 & 22). Castle also stated:

“Rapier play, coarse as it might seem to modern fencers, was such

an improvement over the older-fashioned sword and buckler fighting,

and so much better suited to the requirements of a gentleman...”

(Castle, p. 88). Alfred Hutton in his 1892 book, Old Swordplay,

also declared the old sword and buckler tradition in the age of

the rapier “speedily vanished”. (p. 29). Even fencing

historian J. D. Aylward in 1956 wrote, “Repugnant as all foreign

ideas were to the true born Englishman, Italian conceptions were bound,

in the end, to render his traditional [buckler] sword-play obsolete.”

(Aylward, p. 39). This prejudice is most evident in comments

such as that by the famous Victorian scholar of fencing, Egerton Castle, who referred to “relatively barbarous sword

and buckler” (Castle, p. 20 & 22). Castle also stated:

“Rapier play, coarse as it might seem to modern fencers, was such

an improvement over the older-fashioned sword and buckler fighting,

and so much better suited to the requirements of a gentleman...”

(Castle, p. 88). Alfred Hutton in his 1892 book, Old Swordplay,

also declared the old sword and buckler tradition in the age of

the rapier “speedily vanished”. (p. 29). Even fencing

historian J. D. Aylward in 1956 wrote, “Repugnant as all foreign

ideas were to the true born Englishman, Italian conceptions were bound,

in the end, to render his traditional [buckler] sword-play obsolete.”

(Aylward, p. 39).

It could also be noted that in 1575 a royal entertainment

at Kenilworth for the Queen consisted of jousting tournament and also

sword and buckler combat using weapons without edges or points and no

lunging allowed. (Brailsford, p. 27).

But examining the totality of 16th century fencing, we find

a much more complex picture. It was not the rapier’s development

that “did away” with the sword and buckler (in England or

elsewhere) but the changing nature of Renaissance war that reduced its

utility. As opposed to the anything goes of the battlefield where

the essentially Medieval sword and buckler was well-suited, under urban

conditions, it was also easy to control and allowed for men to make

displays of bravado. Combatants could make wide slashes and smacking

hits and a young man might exert himself in strikes and blows yet not

mortally endanger his foe. This is kind of “play” was

no doubt part of the method’s historical popularity.

Samuel Butler’s Hudibras of 1663 for example makes reference

to how, “As in sword and buckler fight, all blows do on the target

light.” (Craig, p. 19).

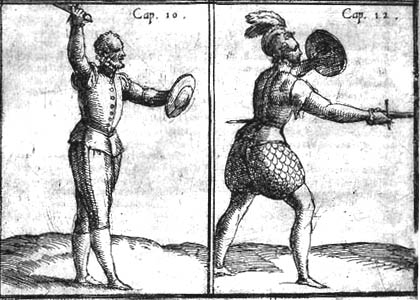

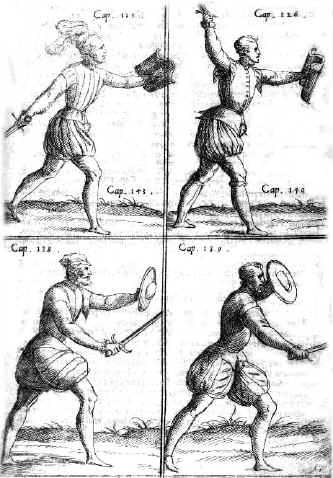

The Italian master Giacomo

Di Grassi himself in his 1570 text offered a section on sword and buckler,

stating, “the Buckler is a weapon very commodious and much used”.

In 1573, the French master Sainct Didier included the buckler and target

in his work on "the Single Sword, Mother of All Arms", calling

them "very useful and profitable for the gentleman to learn, and

for the followers of war" (i.e., common soldiers). Giovanni Antonio

Lovino’s text on the rapier and other weapons from 1580, Traite

d Escrime, also included material on the classic buckler used with

the narrow rapier. Lovino also referred to the sword and buckler as

means of common means of judicial duelling (Lauro attore et Aquilo

reo, con spada et brocchiero). The use of sword and buckler

was in fact still being practiced even in Spain during the late 1500s.

For example, in the late 1580s Juan de Morales was tested in Madrid

for his skill with weapons including sword with assorted bucklers. (Anglo,

Martial Arts, p. 27). A series of images of “sword-dancers”

from Arbeau dated to 1589 shows them with small bucklers and short broad

blades. Even a 1599 fencing manuscript, Arte de Esgrima,

written in Spanish by the Portuguese, Domingo Luis Godinho included

material on the sword and buckler. Yet, much has been made of

the Italianate Englishman, John Florio, who as early as 1578 in his,

First Fruites, was already saying of the buckler, “What

weapon is that buckler? A clownish dastardly weapon”. (Aylward,

p. 35). The Italian master Giacomo

Di Grassi himself in his 1570 text offered a section on sword and buckler,

stating, “the Buckler is a weapon very commodious and much used”.

In 1573, the French master Sainct Didier included the buckler and target

in his work on "the Single Sword, Mother of All Arms", calling

them "very useful and profitable for the gentleman to learn, and

for the followers of war" (i.e., common soldiers). Giovanni Antonio

Lovino’s text on the rapier and other weapons from 1580, Traite

d Escrime, also included material on the classic buckler used with

the narrow rapier. Lovino also referred to the sword and buckler as

means of common means of judicial duelling (Lauro attore et Aquilo

reo, con spada et brocchiero). The use of sword and buckler

was in fact still being practiced even in Spain during the late 1500s.

For example, in the late 1580s Juan de Morales was tested in Madrid

for his skill with weapons including sword with assorted bucklers. (Anglo,

Martial Arts, p. 27). A series of images of “sword-dancers”

from Arbeau dated to 1589 shows them with small bucklers and short broad

blades. Even a 1599 fencing manuscript, Arte de Esgrima,

written in Spanish by the Portuguese, Domingo Luis Godinho included

material on the sword and buckler. Yet, much has been made of

the Italianate Englishman, John Florio, who as early as 1578 in his,

First Fruites, was already saying of the buckler, “What

weapon is that buckler? A clownish dastardly weapon”. (Aylward,

p. 35).

Another

part of the belief that the sword and buckler was “antiquated”

and “obsolete” may be due in part to misunderstanding of George

Silver’s stern complaints against “Italianated” masters

of fence and his evident envy of the prestige they were being giving.

Yet, the root of Silver’s essential grievance was that the rapier

did not prepare men for warfare and national defense, but only for murder

and duelling. He in essence argued further that the rapier was really

nothing that different and could be beaten by man with a short sword

who properly used the core principles of fighting. Somehow over

time understanding of Silver was changed to consideration of him as

simply being “behind the times”. Another

part of the belief that the sword and buckler was “antiquated”

and “obsolete” may be due in part to misunderstanding of George

Silver’s stern complaints against “Italianated” masters

of fence and his evident envy of the prestige they were being giving.

Yet, the root of Silver’s essential grievance was that the rapier

did not prepare men for warfare and national defense, but only for murder

and duelling. He in essence argued further that the rapier was really

nothing that different and could be beaten by man with a short sword

who properly used the core principles of fighting. Somehow over

time understanding of Silver was changed to consideration of him as

simply being “behind the times”.

The Epistle to the 1594

edition of Giacomo Di

Grassi’s, True Arte of Defense,

remarked: “The Sworde and Buckler fight was long while allowed

in England (and yet practise in all sortes of weapons is praisworthie,)

but now being layd downe, the sworde but with Serving men is not much

regarded, and the Rapier fight generally allowed, as a wepon because

most perilous, therefore most feared, and thereupon private quarrels

and common frayes soonest shunned.” The meaning of this passage

is that, while traditional sword and buckler was still good for soldiers,

the rapier was thought best for single encounters however was so dangerous

in them that private fights and duels were more often being avoided.

This corresponds to what we know of the rapier’s use by common

English fighters in London as early as the 1560s –considerably

before it was supposedly first brought to England. The Epistle to the 1594

edition of Giacomo Di

Grassi’s, True Arte of Defense,

remarked: “The Sworde and Buckler fight was long while allowed

in England (and yet practise in all sortes of weapons is praisworthie,)

but now being layd downe, the sworde but with Serving men is not much

regarded, and the Rapier fight generally allowed, as a wepon because

most perilous, therefore most feared, and thereupon private quarrels

and common frayes soonest shunned.” The meaning of this passage

is that, while traditional sword and buckler was still good for soldiers,

the rapier was thought best for single encounters however was so dangerous

in them that private fights and duels were more often being avoided.

This corresponds to what we know of the rapier’s use by common

English fighters in London as early as the 1560s –considerably

before it was supposedly first brought to England.

In Henry Porter’s 1599 play, The Two Angry

Women of Abingdon, we find the line: “Sword and buckler fight

begins to grow out of use...this poking fight of rapier and dagger will

come up, ...a good sword and buckler man will be spotted like

a cat or a rabbit.” (Castle, p. 20). Writing

of English swashbucklers before the advent of rapier fighting, John

Stow in 1631 described how the popular manner of sword brawling

was common until the uncertain and seemingly risky rapier and dagger

came about. Stow described that the “blades”

of London would gather in West Smith-field where they swashed and swinged

their bucklers with much show of fury.[1]

He tells us this areas “was for many years called ‘Ruffians

Hall’, by reason that it was the usual place of frayes, and common

fighting during the time that sword and bucklers were in use…This

manner of Fight, was frequent with all men, untill the fight of Rapier

and Dagger tooke place…But in the ensuing deadly fight of Rapier

and Dagger suddenly suppressed the fighting with Sword and Buckler.”

In act II, scene iii, of Sir Thomas Middleton's play, The Phoenix

(first printed in 1630 but written as early as 1603) in justice

Tangle's legal metaphor laced duel with the lawyer, Falso, he included

the following exchange:

Tangle: "Oh, that's out of use now! Sword and buckler was call'd

a good conscience, but that weapon's left long ago; that was too manly

a fight, too sound a weapon for these our days. 'Slid, we are scarce

able to lift up a buckler now, our arms are so bound to the pox; one

good bang upon a buckler would make most of our gentlemen fly i' pieces;

'tis not for these linty times. Our lawyers are good rapier and dagger

men; they'll quickly dispatch your money."

Falso: "Indeed, since sword and buckler time, I have observ'd

there has been nothing so much fighting; where be all our gallant

swaggerers? There are no good frays o' late."

Tangle: "Oh, sir, the property's altered; you shall see less

fighting every day than other, for every one gets him a mistress,

and she gives him wounds enow; and, you know, the surgeons cannot

be here and there, too: if there were red wounds too, what would become

of the Rheinish wounds?"

According to Stow then, it

was the common serving man who changed his street fighting habits

as a result of the introduction of the rapier. Stow

also stated “it was usuall to have Frayues, Fights, and Quarrells,

upon the Sundayes and Hollidayes, sometimes twenty, thirty, and forty

Swords and Bucklers, halfe against halfe, as well as quarells of appointment

as by chance…” These sword and buckler brawls were

frequently fought only to “dry blows” or hits with the flat

of the blade drawing no blood. (Craig, p. 8). Stowe went on to

reveal that “in the Winter season, all the high steetes, were much

annoyed and troubled with hourely frayes, of sword and buckler men,

who tooke pleasure in that bragging fight; and…they made great

shew of much furie, and fought often.” (Stow, p. 1024). According to Stow then, it

was the common serving man who changed his street fighting habits

as a result of the introduction of the rapier. Stow

also stated “it was usuall to have Frayues, Fights, and Quarrells,

upon the Sundayes and Hollidayes, sometimes twenty, thirty, and forty

Swords and Bucklers, halfe against halfe, as well as quarells of appointment

as by chance…” These sword and buckler brawls were

frequently fought only to “dry blows” or hits with the flat

of the blade drawing no blood. (Craig, p. 8). Stowe went on to

reveal that “in the Winter season, all the high steetes, were much

annoyed and troubled with hourely frayes, of sword and buckler men,

who tooke pleasure in that bragging fight; and…they made great

shew of much furie, and fought often.” (Stow, p. 1024).

More

than 40 years before Stow wrote about the rapier supplanting the traditional

English sword and buckler tradition, the traveler Fynes Moryson described

it in his itinerary in the 1590s, writing that: "Of olde, when

they were senced with Bucklers…nothing was more common with them

then to fight about taking the right or left hand, or the wall, or upon

any unpleasing countenance. Clashing of swords was then daily musike

in every streete, and they did notionely fight combats (Moryson, p.

28). More

than 40 years before Stow wrote about the rapier supplanting the traditional

English sword and buckler tradition, the traveler Fynes Moryson described

it in his itinerary in the 1590s, writing that: "Of olde, when

they were senced with Bucklers…nothing was more common with them

then to fight about taking the right or left hand, or the wall, or upon

any unpleasing countenance. Clashing of swords was then daily musike

in every streete, and they did notionely fight combats (Moryson, p.

28).

William Kemp’s ballad of 1600, Nine Daies Wonder, also

lamented the decline of sword and buckler fencing in the path of the

new foining fence: “Yet all my Hoast remembers not. Ketsfield and

Muselborough fray, Were batlles fought but yesterday. O’ twas a

goodly matter then, To see your sword and buckler men; They would meete

them every where: And now a man is but a pricke, A boy arm’d with

a poating sticke, Will dare to challenge Cutting Dicke. O’ t’is

a world the world to see, But twill not mend for thee nor mee.”[2]

Alluding to the rise of rapier fencing in his 1620, Abortive of

an Idle Houre, Thomas Wroth wrote of a time "When Sword and Buckler

was in estimation…then a man might have some play; But since this

noble fight grew out of fashion, A boy might kill a man in any fraye."

(p. 39.)

Despite several statements to the contrary, the

rapier was actually in use among common fencers in England as early

as the 1560s. For example, in 1568 the London Company

of Masters had already begun to include the rapier in their training

and Prize contests. (Berry, p. 109 & 47). So, the transition from sword and buckler to rapier (at least

in England) was hardly sudden. It appears more than a generation passed

between its introduction in the 1560s to the nostalgic reflection of

the 1590s.

Thomas

Fuller in his 1662, The History of the Worthies of England

(Everyman Edition) described “swashblucker” as coming from

the action of “swashing and making a noise on the buckler.”

Apparently they would strike on their own bucklers with their swords

during fighting. Similarly, Baret’s Alvearie of 1573 mentioned

“to swash or to make a noise with swordes against tergats”

while Ben Johnson in his early 17th century play, Staple

of News, included the line, “I do confess a swashing blow”.

(Craig, p. 10). Shakespeare in Romeo and Juliet also has the

Capulet serving man Gregory make his “swashing blow” (i.e.,

a wide cut). John Florio also mentions, “A bravo, a swashbuckler,

one that for money and good cheere will follow any man to defend him;

but if any danger come, he runs away the first, and leaves him in the

lurch.” And yet, in 1602 William Bass wrote a religious study

that metaphorically referred faith to the confidence found in the “Sword

& Buckler” as “The Serving Man’s Defence.” Thomas

Fuller in his 1662, The History of the Worthies of England

(Everyman Edition) described “swashblucker” as coming from

the action of “swashing and making a noise on the buckler.”

Apparently they would strike on their own bucklers with their swords

during fighting. Similarly, Baret’s Alvearie of 1573 mentioned

“to swash or to make a noise with swordes against tergats”

while Ben Johnson in his early 17th century play, Staple

of News, included the line, “I do confess a swashing blow”.

(Craig, p. 10). Shakespeare in Romeo and Juliet also has the

Capulet serving man Gregory make his “swashing blow” (i.e.,

a wide cut). John Florio also mentions, “A bravo, a swashbuckler,

one that for money and good cheere will follow any man to defend him;

but if any danger come, he runs away the first, and leaves him in the

lurch.” And yet, in 1602 William Bass wrote a religious study

that metaphorically referred faith to the confidence found in the “Sword

& Buckler” as “The Serving Man’s Defence.”

So

while the sword and buckler was losing its value in the late 1500s,

its legacy was still surviving with the use of rapier and buckler. Salvatore

Fabris for example included material on rapier and buckler in his 1606

fencing text and even Camillo Pallavicini volume two of his 1673, Scherma

Illustrata, was still including material on facing the rapier and

buckler. So

while the sword and buckler was losing its value in the late 1500s,

its legacy was still surviving with the use of rapier and buckler. Salvatore

Fabris for example included material on rapier and buckler in his 1606

fencing text and even Camillo Pallavicini volume two of his 1673, Scherma

Illustrata, was still including material on facing the rapier and

buckler.

A Re-evaluation

Given

the strong connections between Medieval and Renaissance fencing methods,

there does not seem to have been much more that was added to the sword

and buckler method during the 16th century. Eventually,

the sword and buckler method, increasingly irrelevant in European warfare

seeing more and more firearms, became less convenient for urban wear

as well. The quick-thrusting farther-reaching rapiers could often

outmaneuver them in single combat and duel. The result was that

the sword and buckler survived past the 17th century only in the old

English schools of defence and then among the early 18th

century “gladiator” prize shows. Given

the strong connections between Medieval and Renaissance fencing methods,

there does not seem to have been much more that was added to the sword

and buckler method during the 16th century. Eventually,

the sword and buckler method, increasingly irrelevant in European warfare

seeing more and more firearms, became less convenient for urban wear

as well. The quick-thrusting farther-reaching rapiers could often

outmaneuver them in single combat and duel. The result was that

the sword and buckler survived past the 17th century only in the old

English schools of defence and then among the early 18th

century “gladiator” prize shows.

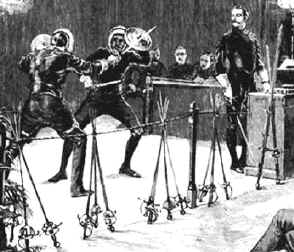

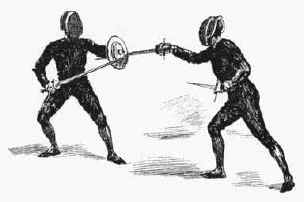

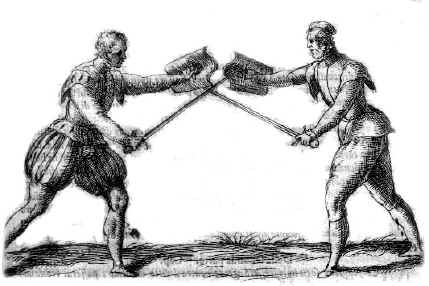

Yet, as the images here

suggest, unquestionably this tradition was a deep part of Western fencing

for centuries within a variety of conditions. In fact, given the

range of evidence we have for the sword and buckler, in literature and

art, as an established way of fighting in the Middle Ages, there is

every reason to believe it was actually more common than was

fighting with a sword and shield. The general historical impression

is that variously shaped shields (i.e., defensive implements worn

on the arm as opposed to carried in the hand) were by far more

common among foot soldiers. While this may have been true before

the 14th century, it appears not to be the case from after

that period. The widespread use of the sword and buckler is evidence

of its utility and effectiveness. With straight or curved blades such

a system of fighting was popular around the world since ancient times

and in some areas survived into the 20th century.

Whether with a tapering cut-and-thrust blade or a wider cutting one,

the sword and buckler represents an effective fighting method capable

of dealing with larger shields or longer swords as well as staff weapons.

With the current revival of study of Renaissance martial arts the versatile

art of sword and buckler fencing is being appreciated once more. Yet, as the images here

suggest, unquestionably this tradition was a deep part of Western fencing

for centuries within a variety of conditions. In fact, given the

range of evidence we have for the sword and buckler, in literature and

art, as an established way of fighting in the Middle Ages, there is

every reason to believe it was actually more common than was

fighting with a sword and shield. The general historical impression

is that variously shaped shields (i.e., defensive implements worn

on the arm as opposed to carried in the hand) were by far more

common among foot soldiers. While this may have been true before

the 14th century, it appears not to be the case from after

that period. The widespread use of the sword and buckler is evidence

of its utility and effectiveness. With straight or curved blades such

a system of fighting was popular around the world since ancient times

and in some areas survived into the 20th century.

Whether with a tapering cut-and-thrust blade or a wider cutting one,

the sword and buckler represents an effective fighting method capable

of dealing with larger shields or longer swords as well as staff weapons.

With the current revival of study of Renaissance martial arts the versatile

art of sword and buckler fencing is being appreciated once more.

|

The preceding material was excerpted a forthcoming

book on Historical Fencing. © Copyright 2002 by John Clements.

Footnotes for Part 4

[2] William

Kemp. Kemp’s Nine Daies Wonder, Printed by E.A. for

Nicholas Ling, London, 1600.

|