|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

Sword

Fighting is Not What You Think... Sword

Fighting is Not What You Think...So, your sword fighting with Medieval and Renaissance blades ...How to do so effectively? How do you so authentically? Well, what it's about is as much a matter of what you don't do as it is a matter what you must do. And in both cases virtually everything you think you know is wrong. By John Clements To borrow a famous line, the problem with most people trying to understanding the true nature of historical sword combat is not that they're ignorant; it's just that they know so much that isn't so.  It's amazing really, how a subject that so permeates our modern pop

culture and is so ubiquitous is one which virtually no one any longer

has any real world experience in nor pursues for it's original function.

The truth is, that most all our conceptions of sword fighting get it

wrong. The reality of it is not what you think it is. It's amazing really, how a subject that so permeates our modern pop

culture and is so ubiquitous is one which virtually no one any longer

has any real world experience in nor pursues for it's original function.

The truth is, that most all our conceptions of sword fighting get it

wrong. The reality of it is not what you think it is.Face it, some readers will really get offended if you dare to suggest that they don't have an accurate conception of sword fighting. Fanboys especially will take it as a personal insult to their very identify when you challenge their assumptions. It's pretty silly, since no one of them relies on this skill for self-preservation nor makes it their profession. Plus, nearly everyone gets their information and opinions on it from the same essential sources: TV, movies, fantasy literature, video games, cartoons, comic books, dinner-theaters and renn-fairs fight shows. But where do those sources get their notions?  Almost

entirely from experience with sport fencing, Asian martial art styles, and

pretentious historical role-playing societies. Yet, all these sources derive

their conceptions of it from still earlier ones. And so on and so on. Where

then did most of today's ideas on historical sword fighting originate? When

we trace it all back, we find romantic beliefs about the nature of swordsmanship

among knights and cavaliers almost all started with ignorant Victorian-age

prejudices. Almost

entirely from experience with sport fencing, Asian martial art styles, and

pretentious historical role-playing societies. Yet, all these sources derive

their conceptions of it from still earlier ones. And so on and so on. Where

then did most of today's ideas on historical sword fighting originate? When

we trace it all back, we find romantic beliefs about the nature of swordsmanship

among knights and cavaliers almost all started with ignorant Victorian-age

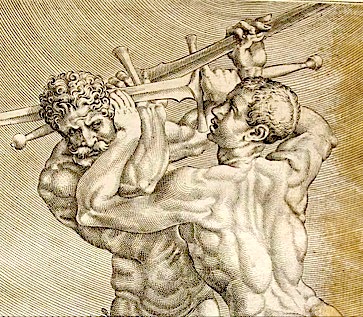

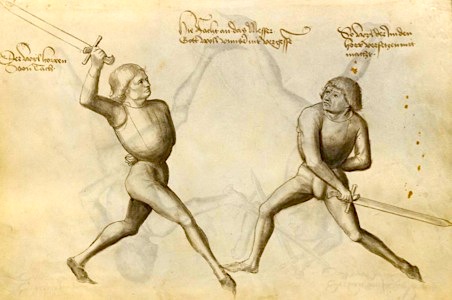

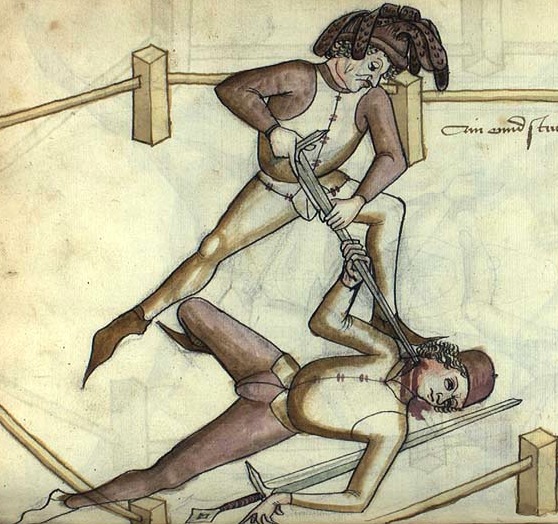

prejudices.Fortunately, during the Medieval and Renaissance eras there were produced hundreds of detailed instructional manuals by expert Masters of Defence. These knights and professional instructors in arms wrote and illustrated immense technical treatises and books on their "science of self-defense." Intended to preserve their secrets or instruct their students and patrons, these little-known works, some in excess of six hundred pages, represent time-capsules of the actual fighting systems and proven combative disciplines used at the time. Focused mostly on swordsmanship, these handbooks and study guides reveal highly sophisticated combat teachings. Further, their content and presentation is unmatched by any martial 1arts literature from anywhere in the world. ...And we have dozens of them.  Only

recently in the last decade or so has this extraordinary and all but forgotten

material finally come to be properly examined and studied. Reconstruction

of these remarkable teachings offers an unparalleled view into how fighting

men prepared and trained themselves for duels, street-fights, and

battlefield encounter. Their manner of fighting with swords is not the classical

Western style we see today, which is largely a contrived 19th-century gentleman's

version of a narrow, aristocratic Baroque style. What the surviving sources

show us is wholly different from the familiar pop-culture version as well

as being dramatically distinct from what has gone on for years in assorted

reenactments and contrived living-history efforts. Rather, Medieval and

Renaissance sword fighting was a hell of a lot more violent, brutal, ferocious,

and astonishingly effective. The way in which these swords were held, the

way they can be maneuvered, and the postures and motions involved, differ

substantially from common presumptions and modern-era fencing styles. Only

recently in the last decade or so has this extraordinary and all but forgotten

material finally come to be properly examined and studied. Reconstruction

of these remarkable teachings offers an unparalleled view into how fighting

men prepared and trained themselves for duels, street-fights, and

battlefield encounter. Their manner of fighting with swords is not the classical

Western style we see today, which is largely a contrived 19th-century gentleman's

version of a narrow, aristocratic Baroque style. What the surviving sources

show us is wholly different from the familiar pop-culture version as well

as being dramatically distinct from what has gone on for years in assorted

reenactments and contrived living-history efforts. Rather, Medieval and

Renaissance sword fighting was a hell of a lot more violent, brutal, ferocious,

and astonishingly effective. The way in which these swords were held, the

way they can be maneuvered, and the postures and motions involved, differ

substantially from common presumptions and modern-era fencing styles.What we know now about sword fighting from the documented historical teachings and methods is that in earnest combat: You don't stand still. The sources specifically tell us to be in constant motion. You don't just dance around. The sources specifically tell us to cover and close in. You don't just parry and riposte. The sources specifically tell us not to try to block. You don't attempt to be passive or stay defensive. The sources tell us in particular to be aggressive, audacious, and take the initiative. You don't try to just win the range and timing by sneaking out blows and feints. You seek to displace the adversary's blows with counter-strikes timed in the middle of their action. You don't just hit out wildly or bash on their weapon. The sources tell us specifically to intercept and stifle their attacks by binding on their weapon and using body leverage. And you don't try to statically receive blows of their edge on your own edge, but set them aside with your flat, or better still, counter-hit them with your edge against their flat, even as edges themselves will readily clash in closing to bind. And lastly, both thrusting and cutting as well as grappling were always recognized as integral components for wielding all swords and weapons --armored or unarmored, on foot or horseback. The secret to all this we're told is not difficult and it is not a matter of having a repertoire of techniques nor just good reflexes and coordination with decent conditioning. It's about knowing and applying a handful of key principles. It's about adversarial perception, timing, distance, leverage, and technique, all used in good martial spirit. Thus, European longswords, arming-swords, falchions, and rapiers are gripped and manipulated in vicious ways I guarantee you have never seen the likes of in any cinematic or video game fight scene. How do I know all this? Because it's my job to know.  I've

been studying historical sword combat for over three decades and teaching

it professionally for more than ten years. I make my living writing and

researching on the subject and operate the world's only private facility

dedicated exclusively to the craft. I've taught and presented on it in 15

countries on four continents, written several books, lectured and presented

at arms museums and universities around the world, appeared in numerous

documentaries, and have published dozens of articles on the topic. I've

consulted for the gaming and entertainment industry, demonstrated at academic

conferences, and my training program in this field is the most developed

and authoritative modern curriculum on the subject available. I've trained

with, cut with, sparred with, and handled more kinds of historical European

swords than probably anyone else alive today. As a fencing historian and

recognized weapons expert, I am the world's leading

proponent and foremost authority on the use of historical European arms

and armor. I've made study of swords in the Renaissance --their forms, techniques,

and wounds --my special focus. It's my life's work, my career, and my passion.

I am an accomplished martial artist teaching authentic art of Renaissance

fencing following the genuine source teachings. I am no stunt-fighter, costumed

performer, nor showman entertainer. I am a swordsman. I've

been studying historical sword combat for over three decades and teaching

it professionally for more than ten years. I make my living writing and

researching on the subject and operate the world's only private facility

dedicated exclusively to the craft. I've taught and presented on it in 15

countries on four continents, written several books, lectured and presented

at arms museums and universities around the world, appeared in numerous

documentaries, and have published dozens of articles on the topic. I've

consulted for the gaming and entertainment industry, demonstrated at academic

conferences, and my training program in this field is the most developed

and authoritative modern curriculum on the subject available. I've trained

with, cut with, sparred with, and handled more kinds of historical European

swords than probably anyone else alive today. As a fencing historian and

recognized weapons expert, I am the world's leading

proponent and foremost authority on the use of historical European arms

and armor. I've made study of swords in the Renaissance --their forms, techniques,

and wounds --my special focus. It's my life's work, my career, and my passion.

I am an accomplished martial artist teaching authentic art of Renaissance

fencing following the genuine source teachings. I am no stunt-fighter, costumed

performer, nor showman entertainer. I am a swordsman. So, when I say we know a great deal now about how historical sword fighters actually trained, what equipment they used, what exercises they undertook, what the outcomes were of their efforts at self-protection in single-combats or war, I can speak with conviction and write with confidence. From my vantage point my core assumptions on the topic carry a certain gravitas. There is little speculation or conjecture, no imagined theories or concocted assumptions at work, only sound interpretation and application of real world skills with accurate blades. And the questions I seek answers to are not ones most people would even know to ask.   Despite

the many people now claiming to be studying the historical teachings on

Medieval and Renaissance swordsmanship, in their practices the majority

invariably don't employ the correct postures, don't use the proper movements,

don't apply the central tenets, and instead typically reduce it all down

to adolescent sword-tagging games. In my own efforts, my senior students

and I have achieved near textbook application of what is described in the

sources. Tellingly, our form in sparring is identical to our form in drill

and exercise while matching that in the sources. By contrast, we regularly

witness countless others struggling with basic execution of essential moves,

performing techniques too softly and slowly, oblivious to the requisite

force and speed intrinsic to the craft, or else excluding crucial moves

altogether from their play-fighting contests. Despite

the many people now claiming to be studying the historical teachings on

Medieval and Renaissance swordsmanship, in their practices the majority

invariably don't employ the correct postures, don't use the proper movements,

don't apply the central tenets, and instead typically reduce it all down

to adolescent sword-tagging games. In my own efforts, my senior students

and I have achieved near textbook application of what is described in the

sources. Tellingly, our form in sparring is identical to our form in drill

and exercise while matching that in the sources. By contrast, we regularly

witness countless others struggling with basic execution of essential moves,

performing techniques too softly and slowly, oblivious to the requisite

force and speed intrinsic to the craft, or else excluding crucial moves

altogether from their play-fighting contests.  It

goes without saying that popular culture today, including the closet-industry

of self-certifying professional stunt fencers whose job it is to fake fights

for movies and television, have no real clue as to what actual bladed combat

was really like. Why? For the simple reason that to fake it you first have

to know it. You can't effectively pretend to do what you haven't legitimately

reconstructed and revived as an authentic fencing method to begin with.

When your job is not to accurately restore genuine sword combat teachings

as real martial arts, but to instead safely create merely an illusion of

fighting, to exaggerate its motions for entertainment with dramatic license,

well then, self-defense reality is the least of your concerns. Stage-combatants

and theatrical fencers are under no obligation (nor much expectation) to

present things realistically, accurately, or martially --and indeed, they

haven't now for generations. Besides, what authority is going to argue with

them anyway? Certainly not producers, directors, writers, or the viewers

who know even less than they do about things. Thus, long bombarded with

artificial and convoluted depictions, the public is continually misinformed,

the truth of how humans react in close combat is habitually distorted, and

the historical reality of sword fighting perpetually misrepresented. It

goes without saying that popular culture today, including the closet-industry

of self-certifying professional stunt fencers whose job it is to fake fights

for movies and television, have no real clue as to what actual bladed combat

was really like. Why? For the simple reason that to fake it you first have

to know it. You can't effectively pretend to do what you haven't legitimately

reconstructed and revived as an authentic fencing method to begin with.

When your job is not to accurately restore genuine sword combat teachings

as real martial arts, but to instead safely create merely an illusion of

fighting, to exaggerate its motions for entertainment with dramatic license,

well then, self-defense reality is the least of your concerns. Stage-combatants

and theatrical fencers are under no obligation (nor much expectation) to

present things realistically, accurately, or martially --and indeed, they

haven't now for generations. Besides, what authority is going to argue with

them anyway? Certainly not producers, directors, writers, or the viewers

who know even less than they do about things. Thus, long bombarded with

artificial and convoluted depictions, the public is continually misinformed,

the truth of how humans react in close combat is habitually distorted, and

the historical reality of sword fighting perpetually misrepresented.  It's

not as if the multitude of disparate opinions and diverse (often mutually

exclusive) views about sword fighting out there are all somehow a small

part of a larger truth or even anywhere near an emerging consensus. It's

more like they represent a near infinite collection of ignorance, faulty

clichés, erroneous assumptions, and sheer fantasy mixed with a little

actual wisdom. It's

not as if the multitude of disparate opinions and diverse (often mutually

exclusive) views about sword fighting out there are all somehow a small

part of a larger truth or even anywhere near an emerging consensus. It's

more like they represent a near infinite collection of ignorance, faulty

clichés, erroneous assumptions, and sheer fantasy mixed with a little

actual wisdom.

When you think about it, men-at-arms and members of fighting guilds or

schools of defence in the Medieval and Renaissance eras were people who

for most of their adult lives trained with weapons in close combat

skills for hours a day and had done so since youth. It's somewhat

preposterous then for modern people dabbling in it once a week or so to

imagine that after a few years playing with scraps of information they

have reached a reasonable facsimile of forgotten arts, rather than some

mild-mannered version for recreation. But, this is in fact what is

mostly done today, whether those doing so can admit it or not. In many

ways, this truth is reflected, tacitly at least, or unconsciously

perhaps, in the way people recreationalize it, fantasize it, sportify

it, and trivialize it, as opposed to pursuing it out of genuine love for

history, heritage, and martial spirit --with all the consummate

character, virtue, and athleticism that such a discipline demands.

It was in 1734 that the Baroque fencing master, Monsieur L'Abbat, keenly observed a fundamental truth about the craft the truth of which hold even more so today: "Though there are people of a bad taste in every Art or Science, there are more in that of fencing than in others, as well by reason of little understanding of some teachers, as of the little practice of some learners, who not acting upon a good foundation, or long enough, to have a good idea of it, argue so weakly on this exercise…" I have witnessed this countless times in my life.

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||