|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|  |

|

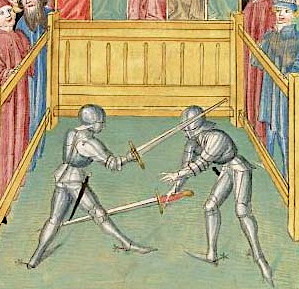

For centuries, the fight of double-edged arming-sword with a small

buckler or larger shield was preferred in all manner of chivalric and

judicial duels. Knightly challenges to feats of arms in the chansons and

tales were often described in terms of sword duels on foot. In time

these short swords were largely supplanted for dueling by a variety of

double-handed war-swords. The larger great-sword, the armor-piercing estoc,

assorted single-edged falchions, and later the saber (in both heavy

military and light civilian forms), were all popular choices at one time

or another. The various designs of slender military side-sword were a

common choice throughout the 16th century either on their own or more

often accompanied by dagger or buckler. Versions of these swords found

continual use in duels for the next two centuries. As larger military

swords fell out of use it's easy to understand how more compact

cut-and-thrust designs would become a common choice for dueling.

|

|  |

|

It

was in Renaissance Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries that the

sword duel arguably reached its zenith with all manner of punctillios and cartellos.

The ending of the feudal-era, the rise of larger cities, and the

general banning of judicial combats by the late 1540s provoked a

reaction. The abandonment as a legal means of publicly

settling conflicts directly increased the popularity of its

alternative. Quarrels over issues of honor and reputation would be

settled by the parties themselves through their own means. In that

environment, every gentleman or man-at-arms with such pretensions owned

some form of sword. Typically, a man would fight a duel with his own

personal sword, that being the same one he used in war and carried on

his person, but at other times matching swords were pre-selected so that

neither was longer or lighter than the other. By the 16th century,

special pairs of identical swords, called a case or brace, were kept by

neutral third-parties for this very reason.

It

was in Renaissance Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries that the

sword duel arguably reached its zenith with all manner of punctillios and cartellos.

The ending of the feudal-era, the rise of larger cities, and the

general banning of judicial combats by the late 1540s provoked a

reaction. The abandonment as a legal means of publicly

settling conflicts directly increased the popularity of its

alternative. Quarrels over issues of honor and reputation would be

settled by the parties themselves through their own means. In that

environment, every gentleman or man-at-arms with such pretensions owned

some form of sword. Typically, a man would fight a duel with his own

personal sword, that being the same one he used in war and carried on

his person, but at other times matching swords were pre-selected so that

neither was longer or lighter than the other. By the 16th century,

special pairs of identical swords, called a case or brace, were kept by

neutral third-parties for this very reason.

One cannot consider the sword in duel without examining its nature

and especially the role of the dueling culture in Western civilization.

Unquestionably, no sword in history is as closely associated with the

duel of honor as is that most unique of Renaissance weapons, the slender

foyning rapier. No other sword is as identifiable with the very idea of

the duelist. Though it came into being for urban street fights among

the working class (in an age when guns were becoming increasingly

formidable), within a few generations it was almost the exclusive focus

of fencing masters increasingly concerned with solving the intricacies

of its method in private duel. The evolution of both its blade and hilt

followed directly from this concern. Frequently employed with a matching

dagger and even a simple cloak, the eventual preference for gentlemen

duelists was to use it on its own.

The finesse of a long narrow blade with a quick piercing reach was well

received by duelists and within a generation adopted as their preferred "go-to"

weapon. The danger of fighting unarmored with a slender thrusting sword, with

its blinding speed, deceptive reach, and particular angling of attack

meant that men –especially those still unfamiliar with such fencing–

were very easily wounded. It wasn't that the rapier was intrinsically

more lethal than the fearsome cleaving blows of wider cutting

blades, but that because puncturing stabs simply could not be treated in

the manner of slashes and cuts the death rate due to rapier duels

exploded. There are even notable examples of men seeking out a noted

fencing master for an upcoming judicial combat or before issuing a

challenge in hope of learning some secret technique or special move that

might give them advantage.

|

|

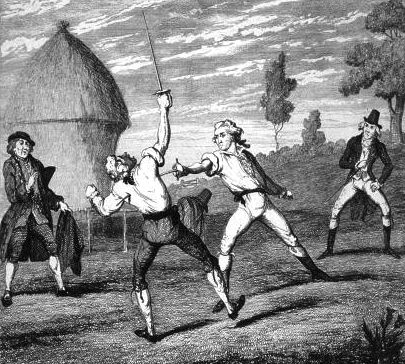

The Baroque-era continued the dueling trend as French aristocratic

circles raised the formality and etiquette surrounding the sword duel to

a level never seen before even as firearms were now entirely dominating

warfare. Here the narrow small-sword, as court-sword or walking-sword,

earned preeminence among duelists over military cutlass and cavalry

saber. No other sword form developed so specifically for unarmored

civilian self-defense. Its very function served foremost for dueling

against another small-sword. Though seemingly "dainty", this shorter

thinner blade came on the scene as a less obtrusive personal weapon with

no necessity of encountering the diverse arms and armor of its older

Renaissance cousin. There are plenty of accounts of small-sword duels

being vicious and brutal exchanges devoid of propriety. But comportment

and deportment in a duelist was a product of the Age. While the average

Baroque swordsman might have no compunction whatsoever about coldly

piercing his adversaries chest with his point, striking a fellow

gentleman's face, grabbing his garments, or resorting to unarmed blows

and "vulgar" grappling would be viewed as unseemly and uncouth.

In

the long history of fencing, the idea of two swordsman willing to

non-lethally cross weapons in order to test one another's metal as a

practice fight with training weapons, even at the risk of serious

injury, is hardly uncommon. Indeed, it was likely a fairly regular

occurrence. But this does not rise to the category of duel. Even when

two rival swordsmen had a personal enmity for one another, it is the

intent to seek something more than just "winning" a mock fight on a

given occasion that is the defining characteristic of the true duel. For

encounters to be considered duels there must be something personal at

stake between them. The parties involved must be risking something

beyond a mere test of mutual prowess. There must be the goal of seeking

reparation for tarnished reputation or personal slight by the act of

real violence and the possibility of real injury or death. There must be

a wrong that can only be righted by force of arms, not a sudden brawl

in anger.

In

the long history of fencing, the idea of two swordsman willing to

non-lethally cross weapons in order to test one another's metal as a

practice fight with training weapons, even at the risk of serious

injury, is hardly uncommon. Indeed, it was likely a fairly regular

occurrence. But this does not rise to the category of duel. Even when

two rival swordsmen had a personal enmity for one another, it is the

intent to seek something more than just "winning" a mock fight on a

given occasion that is the defining characteristic of the true duel. For

encounters to be considered duels there must be something personal at

stake between them. The parties involved must be risking something

beyond a mere test of mutual prowess. There must be the goal of seeking

reparation for tarnished reputation or personal slight by the act of

real violence and the possibility of real injury or death. There must be

a wrong that can only be righted by force of arms, not a sudden brawl

in anger.

This definition of dueling blurs because throughout history young men of

hot temper have often "rumbled" for the mere pleasure of earning renown

from their peers or just reveling in displays of armed aggression

against seemingly worthy foes. In cultures where sword duels existed

there were almost always two forms: an unregulated informal kind,

typically occurring on short notice, and an approved version with

certain rules and customs. The latter usually restricted lethality by

proscribing the arms allowed, preselecting the time, and delineating the

permitted space. But for every record of a regulated duel there is

almost always an exception.

|

While there are sporadic instances throughout history of single

combat challenges on the battlefield or in feats of arms as a means of

seeking valor, it was only within Western Europe that a true dueling

culture of swordsmanship found full expression. Both the ancient Greeks

and the Norse recognized occasions for individual challenges to settle

disagreements or accusations sword-to-sword and there are a few recorded

instances of samurai duels, such as those by the famous, Miyamoto

Musashi, in the 17th century. Yet, these took place as exceptions rather

than the rule. Roman gladiators, though usually engaged in single

combats, were not dueling because they very often fought against their

will or against others who did not freely enter the combat. More

importantly, they did not have personal grievance as their cause but

were fighting as spectacle or entertainment (not to mention that such

fights were not necessarily to the death or even to cause serious

injury). Singling out an opponent on the battlefield or being ordered

into the arena is not quite the same as willingly stepping out or

arranging ahead of time to specifically fight one on one without

interference.

There are also notable accounts of rival fight-school challenges at

European festivals and fairs from the late 15th all the way into the

early 18th centuries. Although these used all manner of swords that

could cause serious harm and allowed for cutting blows that frequently

bled their unarmored combatants, they nonetheless had their bouts

arranged as promotional displays and training events. Sometimes there

were personal rivalries and sometimes unintentional deaths occurred. The

public "prize fights", such as held by the London masters of defence,

were public exhibitions to test their students in a series of matches

against their fellows using blunt weapons. These were later revived

commercially as much bloodier "gladiatorial" combat sports in the late

17th century. But this was not about dueling and these were not true

duels.

There have been duels with knives, with spears, even axes and plenty

with pistol. Many also took place on horseback. But it was always the

sword on foot that remained the premier individual arm of self-defense

suited to all occasions. The selection of the sword as the weapon of

choice for a duel had deliberate meaning. The sword was an armament

whose only function was combat —not hunting or farm labor in the manner

of an axe, pole-arm, or bow. Using a sword implied knowledge of

swordsmanship, which meant being educated in arms as a member of the

military class or nobility (or having pretensions to such). In a social

and cultural context the sword was both representative as well as

symbolic of status, faith, and honor. With the sword you had to get up

close. You had to make physical contact with your adversary. You cannot

engage them without exertion and deliberate intent as well as incurring

danger. The sword gave the duelist satisfaction by his drawing blood in

the face of possible death. When it comes to a sword duel, it's

personal.

|

|

A sword duel is seldom viewed as an act of civility but that's

precisely what it was. All legal and theological arguments against it

aside, the duel served a means of settling conflicts while avoiding

direct homicide. There are no rules when fighting for your life, and

yet, that is exactly what a duel demanded: that in a fight you agree to a

certain set of prohibitions for how to start and how to finish. The

sword duel survived for so long because it provided an outlet. It

channeled natural violent impulses and directed unavoidable hostility by

permitting an acceptable manner of fighting that assured some degree of

fairness and honesty between the combatants. Just as importantly, it

allowed recognition of it among ones social peers. Honor among duelists

was about more than mere reputation or face saving; it was about

behavior, expectation, etiquette, masculine personae, and adherence to a

set of martial norms. The dueling culture was sword culture and there

were many who took delight in it.

It's easy to romanticize sword duels as the manly means to prove

one's worth and reputation while ending private feud and avoiding

vendetta. But just as easily it could be abused, exploited, and produce

nothing but wasteful senseless death. From the record it would seem that

private duels of honor were rarely honorable and seldom private. Nonetheless, it's also easy to

recognize its appeal. If two men agreed to settle a matter between them

by consensual force of arms there was no better way than the honest

clash of steel. To accept such a challenge, to face it down and claim

victory through your own skill, whether the opponent was spared or

slain, was the surest way to defend a smear, insure the value of your

word, or earn renown outside of war. In that regard, the ability to

wield the sword matched with the willingness to use it over such matters

was seen as a sign of character. The paradox of the private duel was

that to earn repute or acquire notoriety, it could not be entirely

private, or else the victor might be construed as having intentionally

arrange a murder by ambuscade. Thus, at least some public witnesses or

neutral spectators were typically required. Avoiding the attention of

the authorities was the catch. In general, dueling was an extralegal

activity of the aristocracy and the state, though issuing numerous bans,

generally turned a blind eye if it were done discretely.

|

|

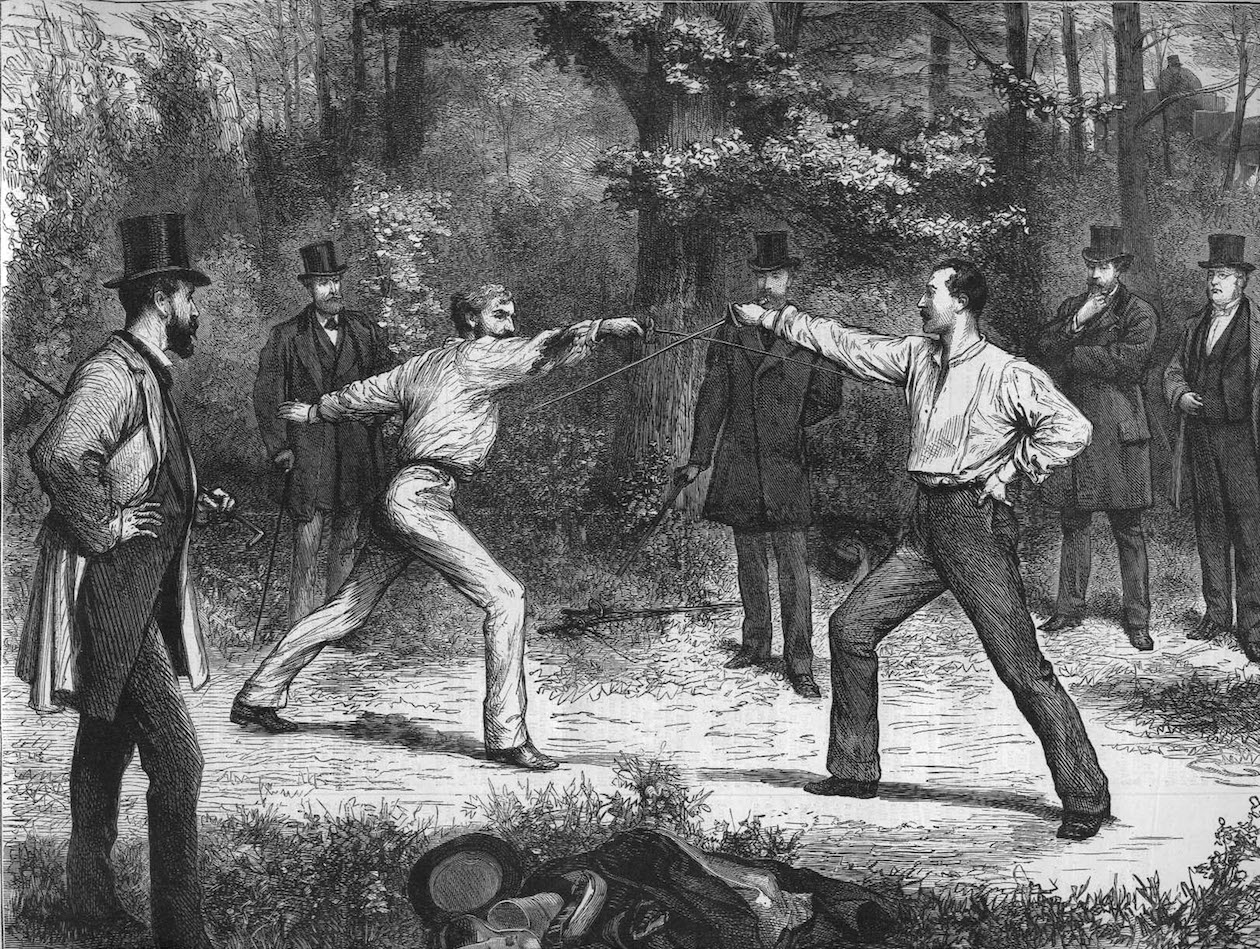

Yet, sword duels could be impromptu affairs with nothing formally

declared and only the understanding that once blades were drawn no one

was going to interfere. There might not even be any explicit expression

of what outcome was expected until it was all over with either one or

possibly both parties wounded or slain. In many cases, the label of

"duel" seems to have been applied to such spontaneous fights after the

fact. To be sure, the formal duel was far less common than were simple

back alleys assaults and gang fights in empty piazzas and wooded paths.

To face off mono-a-mono, having selected one of a pair of equal blades,

and backed by your second, awaiting the command of a neutral third-party

before killing or being killed, was an experience reserved for a select

few. Many sword duels were fought only until the slightest blood was

shed and the aggrieved party satisfied –a result easily achievable by

swords in particular. But many more were expressively fought to the

death.

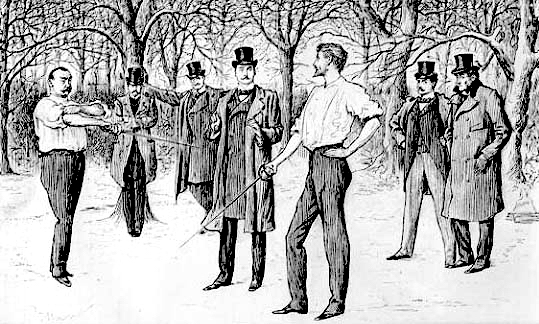

Curiously, as Warfare in the West became more industrial, more

mechanized, and more lethal during the mid-to-late 19th century, Western

fencing became sportified. It transitioned into a safe athletic pastime

and recreational game at the same time the gun-culture entirely took

hold. But the sword duel for matters of personal honor persisted. A

longer and lighter dueling version of the épée' emerged strictly for

conducting such affairs as did a thinner and lighter "civilianized"

sabre. When clerks, lawyers, and journalists could find excuse over any

trivial minutia to "duel" in the park using featherweight weapons

employed in a manner to produce mere pinking wounds, things were reduced

to near farce. As the 20th century approached, sword duels had been

reduced to a highly regulated activity seldom offering any serious

danger to its participants and deaths by sword wound were a rarity.

Meanwhile, the contrived rituals of 19th century German university

"dueling" clubs with their non-lethal blades, diluted their formalized

bouts down to an artificial scar-inducing fetish serving as little more

than "extreme fraternity hazing." It took the horrors of the Great War

of 1914 to not only end the honor culture of Western civilization, but

extinguish entirely the idea that manhood and reputation was best made

worthy by encountering edge or point in ritualized single combat.

|

|

The history of the duel is long and complex but the general idea that

two people may choose to settle a private dispute or resolve a conflict

by mutual consent is an ancient one. There are probably as many

examples of sudden on-the-spot duels taking place as there are those

that required extensive negotiations to arrange. And there are examples

of duels being fought between two parties that had no quarrel or cause

whatsoever between them other than they wished to fight someone or

otherwise thought it expected of them by their peers. For every

reluctant duelist there was the sociopathic bully who purposely sought

out or gave offense in order to provoke a fight he was sure to win. For

every sword duel that ended amicably with the two parties shaking hands

before heading off to share a drink there were perhaps a dozen that

ended in complete animosity with one or both parties mortally wounded.

Nevertheless, there has long been a recognition that among duelists (as

well as competitors in combat sports) that they share an intimacy which

very often ends in mutual respect. There was an honesty found in

allowing two capable individuals to just "fight it out" if they wanted.

The problem was, they usually wanted too often for too stupid a reason.

Again, it's important to understand that social forces have always

had a profound influence on how men choose to defend themselves or

engage in ritual combats. We have to avoid looking at it from our

perspective rather than from the context of the original time and place.

A man who was willing to risk his life and the taking of life at the

point of a sword, yet abide by rules of what was considered decent or

indecent when fighting would be looked upon with admiration and respect

by his peers and opponents alike. If two similar men survived a serious

duel it was often easy for them to forgive and forget not to mention

enjoy the notoriety they had mutually earned regardless of victory so

long as they had both acted with proper decorum.

|

|

|

It's difficult from our perspective today with our instant

communication and global media to grasp that the primacy of individual

dignity was once solely a matter of the local communities within which a

gentleman personally operated. This compelled and demanded he answer

slander and accusation by a willingness to back up his reputation

through skill in arms. A price had to be paid by those who besmirched

him. By providing protocols and structure to interpersonal violence that

would have happened anyway, dueling directed the impulse into the

something less socially damaging than outright open combat. In offering

opportunity for redress a duel was a means of preserving social order

and limiting revenge in a violence prone society accustomed to constant

death. The problem was that it came to generally force those who did not

want to participate in settling "idle quarrels" to do so anyway,

thereby causing a massive and unnecessary loss of life.

With few exceptions, the majority of sword duels we know of are those

occurring among the nobility, recorded by the nobility for a readership

of nobility. They naturally favored accounts that upheld the

aristocracy's ideas about "honorable quarrels." Single combats among the

common folk and duels that did not abide by preferred rules of decorum

and etiquette held little interest to such historians, even as it's the

more unusual duels that tend to stand out to us today. On top of this,

cinematic depictions of sword duels and fictional descriptions in

popular culture invariably overextend sword fights into exaggerated

exchanges of dramatic parry-riposte action. Duels are frequently shown

where disarming the opponent or merely threatening to finish them off is

sufficient to end the affair as the victor proves his superiority as a

swordsman. The reality from the genuine accounts and fencing sources is

that the real things were much shorter and far more violent.

Considerable European literature was certainly produced from the 16th

century onward on either supporting or condemning duels. Arguments were

offered for the virtue of reason over rage as well as what was "just"

or sufficient cause to settle a personal matter by "calling out" the

other party. The truth lies somewhere in between. As the Elizabethan

master of defence, George Silver, counseled in 1599, "Take not arms upon

every light occasion" and "Do not upon every trifle make an action of

revenge or of defence."

Silver gave perhaps the most authoritative disapproval of dueling over the provocation of mere words:

"...he that will not endure an

injury, but will seek revenge, then he ought to do it by civil order and

proof, by good and wholesome laws,

which are ordained for such

causes, which is a thing far more fit and requisite in a place of so

civil a government as we live in, then is the

other, and who so follow these

my admonitions shall be accounted as valiant a man as he that

fights and far wiser. For I see no reason why

a man should adventure his life and estate upon every

trifle, but should rather put up divers abuses offered unto him,

because it is agreeable to the

laws of God and our country."

Yet, while advocating legal recourse for slander, Silver wholeheartedly

endorsed the necessity of armed self-defense whenever necessary:

"Why should not words be answered

with words again, but if a man by his enemy be charged with blows then

may he lawfully seek

the best means

to defend himself and in such a case I hold it fit to use his skill and

to show his force by his deeds..."

Commenting on the topic of provocation by "fighting words" in his

fighting treatise of 1617, the English fencing master, Joseph Swetnam,

observed that: "As there are many men, so they are of many minds, for

some will be satisfied with words, and some must needs be answered with

weapons." Swetnam understood that sometimes some people just needed to

be made to answer. Yet, he further warned the potential duelist to,

"meditate thus with thy self before thou pass thy word to meet any man

in the field." Swetnam still advised, that when you come into the

dangers of the dueling field, "being loath to kill...Then thy enemy, by

sparing him, may kill the, and so thou perish."

The tradition of sword duel survived the advent of firearms even as

ballistic weapons forever ended the primacy of edged weapons in war and

personal defense. The personal quest for prowess and recognition of

skill in a "fairly" contested invitation to bloodshed combine in the

romance of the sword duel. Our modern fascination with it revolves

around longstanding ideas of manliness, the problem of youthful

aggression, and the honing of a warrior spirit. Even the very word

"duel" has come now to mean any type of high stakes struggle between two

opposing parties.

While

dueling might seem like it would just lead to the biggest toughest guy

being free to express invective and make disparagements because he won't

be challenged, that wasn't really the case. The fact is, the duel

actually offered a certain sort of fairness in that weapons are the

great equalizers. Though physical strength and size is a bonus in

fighting, skill supersedes it. It doesn't matter how big and strong you

are when an ordinary sword point can just as easily pierce through your

face or belly and a sharp edge just as easily remove your hand or sever

your kneecap. This is likely why so few historical duels were settled by

fighting unarmed (and why duels with pistols came into being).

Because fencing skill by its nature is about discipline and self-control

it meant you had accomplished some training and were expectedly less

likely to say something rash and impolite. Though there are plenty of

infamous exceptions, generally, people with an appreciation for weapons

and a confidence in using them don't usually go about provoking the

kinds of offensive verbal exchanges that lead to real fights. (One need

only look at online comment threads or Twitter exchanges

—where physical confrontation is an impossibility— discourse is

quick to break down. It's not about being unable to ignore insults but

rather about making dishonorable characters pay a price for disreputable

acts against you.

While

dueling might seem like it would just lead to the biggest toughest guy

being free to express invective and make disparagements because he won't

be challenged, that wasn't really the case. The fact is, the duel

actually offered a certain sort of fairness in that weapons are the

great equalizers. Though physical strength and size is a bonus in

fighting, skill supersedes it. It doesn't matter how big and strong you

are when an ordinary sword point can just as easily pierce through your

face or belly and a sharp edge just as easily remove your hand or sever

your kneecap. This is likely why so few historical duels were settled by

fighting unarmed (and why duels with pistols came into being).

Because fencing skill by its nature is about discipline and self-control

it meant you had accomplished some training and were expectedly less

likely to say something rash and impolite. Though there are plenty of

infamous exceptions, generally, people with an appreciation for weapons

and a confidence in using them don't usually go about provoking the

kinds of offensive verbal exchanges that lead to real fights. (One need

only look at online comment threads or Twitter exchanges

—where physical confrontation is an impossibility— discourse is

quick to break down. It's not about being unable to ignore insults but

rather about making dishonorable characters pay a price for disreputable

acts against you.

Admittedly, there is an undeniable satisfaction in calling out someone

who wronged you and watching them back down out of cowardice or

dishonesty because they're unable or unwilling to match their tough talk

with blows. The fear of physical punishment did indeed deter harsh

words and bad behavior. But, if an opponent was willing to fight and you

were to lose, well, there is still satisfaction in having proved your

willingness to endure the danger of injury or even death over insult or

dishonor. None can deny the respect earned by standing up for yourself

or that, paradoxically, the original offense is mitigated by it. Again,

this is difficult to relate to in our modern age because fighting one to

one over an affront seems like a resort to something primitive and

irrational.

To better understand the role of the sword in duel consider that it

was a personal side-arm closely worn because it was relied on for safety

and survival. It offered an innate capacity to adeptly threaten with

point or edge, to deftly ward off blows, to slash and bash, and to

increase the effectiveness of all this through personal discipline and

study. How could such a valuable object not be highly prized and

lovingly decorated? Curiously, in societies where arms are openly worn

incidents of both sudden violence as well as violent crime are less

frequent. The fact that disrespect and insult can be met with injury or

death does indeed encourage people to better behave themselves around

one another. There was a simple truth at work in an armed society: if

you don't want to risk provoking a duel then avoid angering those who

won't tolerate the indignity of incivility or innuendo. Nothing else

discouraged rudeness more thoroughly –or forced an apology more quickly–

than the possibility of it being answered with a challenge to private

violence. As the erudite swordsman adventurer, Captain Sir Richard

Burton, famously declared in the mid-19th century,"As soon as the sword

ceased to be worn in France, the most polite man became the rudest."

There is an undeniable truth to his observation that in our digital age

of online discourtesy holds growing appeal to the modern student of the

sword.

For historical fencing practitioners today, the interest in how swordsmen once prepared for sword duels they would perhaps never have is really not all that different than our own exploration. One cannot examine either antique swords or authentic teachings for their use without regard to how they applied to the dueling tradition. In that regard, we continue their legacy through our own training. It is this long connection between the duel and the sword, between personal single combat and personal sidearm, that is such a part of why it was the unrivaled weapon of choice for defending honor and seeking private justice. The sword in duel may perhaps even have a history stronger than the sword in war.

See also: The Sword in War

3-2017

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||