|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

|

|

|

In

the past, with few historical exceptions, warriors rarely fought in regulated

ways with standardized equipment. Close combat was a very personal affair,

and as a matter of survival, fighting men relied upon chosen personal

arms with which they were intimately familiar. It's easy for us now from

our modern vantage point to imagine that we can somehow reason out some

better or more logical way history's warriors might have equipped themselves

for battle. But that delusion is sheer ignorant naïveté. They knew what

they were doing.

In

the past, with few historical exceptions, warriors rarely fought in regulated

ways with standardized equipment. Close combat was a very personal affair,

and as a matter of survival, fighting men relied upon chosen personal

arms with which they were intimately familiar. It's easy for us now from

our modern vantage point to imagine that we can somehow reason out some

better or more logical way history's warriors might have equipped themselves

for battle. But that delusion is sheer ignorant naïveté. They knew what

they were doing.

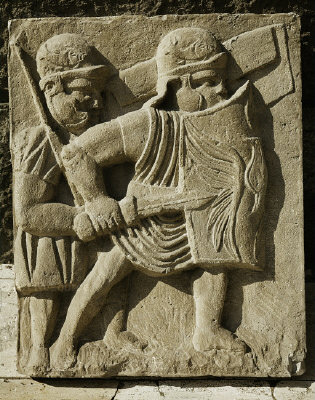

It might seem a suicidal task to charge the impregnable porcupine-like lines of a dense formation of long spears. But on the opposite side, it's not all that much easier to wield a long heavy polearm into the enemy while you're jostling with others on either side, possibly in front, and invariably pressing you from behind. If you're not in the first few ranks, even seeing the opposing troops closing with you becomes difficult. On top of this, keep in mind that in almost any battle there would also likely be some number of troops firing ranged weapons, with still others bearing down on horseback.

Unless you're familiar with the might and agility of a large horse and have experienced what it's like to have some of them coming directly at you at high speed, you simply have no idea how instinctively you'll want to get the hell out of their way. Knowing that there are men on top of them intent on killing you only intensifies the feeling. It's foolish to think you would just stand your ground and strike the legs of the animal or easily stab at either of them with your spear. The next time you're standing next to a mounted police officer, take a long good look at that large animal he's astride and try to visualize that it's angry, scared, kind of pissed off at you, and literally trained to kick your ass. Then think about its rider feeling the same way. And finally, multiply that mounted combat machine by 10 or 20 or 500... Kind of changes your perspective, huh?

|

|

Aside from the historical record from Greece and Rome, we have ample evidence for use of all manner of single and double-hand swords in war. In ancient armies, short swords and large shields were a standard armament of the soldiers who fought with and against the long sarrisa pikes of phalanxes. The same was true for formations of legionnaires armed with their pilum javelins. Byzantine armies added longer arming swords to the spear and shield they equipped their armored foot soldiers and heavy cavalry with. China did much the same at times. The shield walls of Anglo-Saxons held their lines with sword and long axe as much as heavy spear. They were met by sword and shield wielding heavy Norman lancers on horseback. Saracen raiders and Mongol hordes preferred mounted ranged combat with bow and javelins, but were armed with slashing blades and bucklers nonetheless. Japanese feudal armies focused on troops with long and short spears as well as masses of archers both mounted and on foot, yet this did nothing to diminish their interest in carrying the sword to war.

Late Medieval European armies were always a combined-arms operation whether in skirmish, siege, or full field array. The ascendancy of heavy cavalry of fully armored knights with long lance did nothing to discourage men-at-arms from continuing to develop ever more varieties of increasingly specialized sword designs, as well as adapting all manner of agricultural implements into military polearms. While the former was expensive and time-consuming to produce, required a specialized bladesmith, and worked best only with deliberate instruction, the latter was fast and cheap so that common foot soldiers could easily be equipped with minimal training.

|

|

|

In the Renaissance revival of the ancient phalanx, disciplined square formations could hold their own against any mounted threat as well as march their ranks through any shield wall. It took long range ballistic firepower to eventually neutralize them as militarily effective units. But well before that, their utility in war did not vanquish the sword as "queen of weapons." Amidst the chaotic jostling jumble of hedgehog-like shafts, the man who gets up inside with his sword is going to viciously stab and and slash to brutal effect. The surest way to stop him once he's there is to be able to respond in kind with a long knife or a short sword. Among the clashing of hafted weapons, a few two-handed greatswords placed between pikemen and halberdiers could also be ferociously effective by fearsomely slicing and chopping at hands, heads, and shafts alike. It should be no wonder then that double-handed "swords of war" found use for centuries.

|

|

Which brings us to another question I am frequently asked: If swords are so versatile and effective, then why were there ever such things as battle-axes, maces, and war-hammers? Again, there's no short and sweet answer. Some weapons, along with being easier and cheaper to manufacture, require less practice to wield, and in the hands of certain fighters —under particular fighting conditions— are more effective against particular kinds of targets. It's the same reason why there are many different kinds of firearms suited for different combat defense needs. But curiously, the evidence for the sword in Medieval warfare outweighs that for the axe, mace, hammer, and flail.

But the other factor in all this is armor. Virtually no one went to war without some proven form of specialized protective garment. What can make a sword even more effective on the battlefield is when you don't need to have your other hand occupied by a shield because your armor is insuring you against most all of the incidental injuries you'd normally receive. That means gripping your sword not just by the handle with both hands for more powerful blows, but when necessary, grabbing hold of the blade itself and using the weapon like a short spear to stab or leverage blows in up close. These commonplace actions were an intrinsic part of European swordsmanship.

|

|

|

Many Renaissance martial arts treatises describe the value of swordsmanship as the foundational training not just for all manners of single combat and self defense situations, but for the battlefield. This did not change as firearms became the dominant military technology. Even into the early 20th century, the sword continued to be the weapon of choice to accompany the pistol or rifle for light cavalry. In fact, because of its utility and lore, as well as its symbolism and connection to dueling culture, in being carried to war the sword far outlasted all pole-arms.

|

|

|

So, while on the battlefields of history simple shafted weapons were more common and arrows accounted for more death, no one went to war without some sort of personal side arm for close-in defense. More often than not, it was a sword. There was a simple enough matter at work in all this: if your spear was thrown or your halberd shaft broke, you had better draw that blade on your hip and start using it with some skill. Whether long or short, straight or curved, wide or tapered, the sword was indispensable in war.

|

|

See also: The_Sword_in_Duel

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|||