Where's

All the Ground Fighting? Where's

All the Ground Fighting?

Changing our perception of Renaissance unarmed combat

By

John Clements

ARMA Director

I

am not much of a grappler or wrestler and have always promoted staying

away from your opponent and using your weapon (even while emphasizing

to close and fight inside). I have, however, for many years prided myself

on specializing in disarms and trapping techniques, the skills of "sword-taking"

(Schwertnemen). Seizing and takedowns or throws have long been

primary in my opinion over wrestling. In pursuit of armed fighting arts

I have emphasized these teachings among my personal students. I have never

found this approach wanting (I can add that I have a well-earned reputation

for being hard to get a grip on).

Recently, while conversing with a respected European expert on combatives

and self-defense, currently consulting for the US military, I mentioned

how little ground fighting there really was in the Fechtbuchs—despite

many people wanting to now think of Kampfringen as modern jujutsu. My

colleague said he was not at all surprised by my findings. (Curiously,

incidents among US combat personnel in Iraq and Afghanistan have produced

some critical controversy over the predominance of teaching ground fighting

skills within military combatives programs... Too much emphasis on going

to the ground for submissions as athletic exercise. Go figure. I said

the same thing years ago.)

Following

this discussion I decided to take a more careful look through my extensive

collection of unarmed combat images from Medieval and Renaissance artwork,

and sure enough... I can say: Show me the ground fighting! Where

is it? If ground fighting was particularly valued then it is noticeably

under-represented in the very historical examples we rely upon. This realization

came to my attention when I recently tried to gather all the ground fighting

images from the Fechtbuchs for a presentation to a MMA group, but I could

only find a tiny few. I looked through more than a thousand images

from our historical source literature (especially the major German and

Italian works) and all I can find within the fighting manuals of the 15th

and 16th centuries is about a dozen total examples showing unarmed fighters

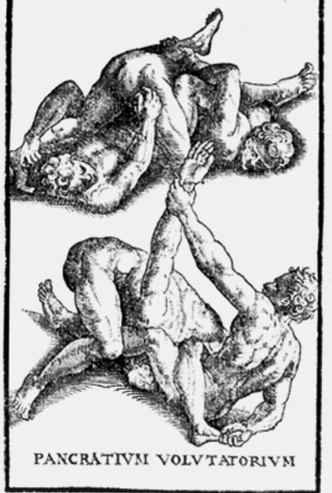

on the ground. (!) In fact, when looking through ancient artwork

on Pankration and Roman unarmed combat sports and fighting arts, I could

only find a handful of ground fighting depictions there as well. Following

this discussion I decided to take a more careful look through my extensive

collection of unarmed combat images from Medieval and Renaissance artwork,

and sure enough... I can say: Show me the ground fighting! Where

is it? If ground fighting was particularly valued then it is noticeably

under-represented in the very historical examples we rely upon. This realization

came to my attention when I recently tried to gather all the ground fighting

images from the Fechtbuchs for a presentation to a MMA group, but I could

only find a tiny few. I looked through more than a thousand images

from our historical source literature (especially the major German and

Italian works) and all I can find within the fighting manuals of the 15th

and 16th centuries is about a dozen total examples showing unarmed fighters

on the ground. (!) In fact, when looking through ancient artwork

on Pankration and Roman unarmed combat sports and fighting arts, I could

only find a handful of ground fighting depictions there as well.

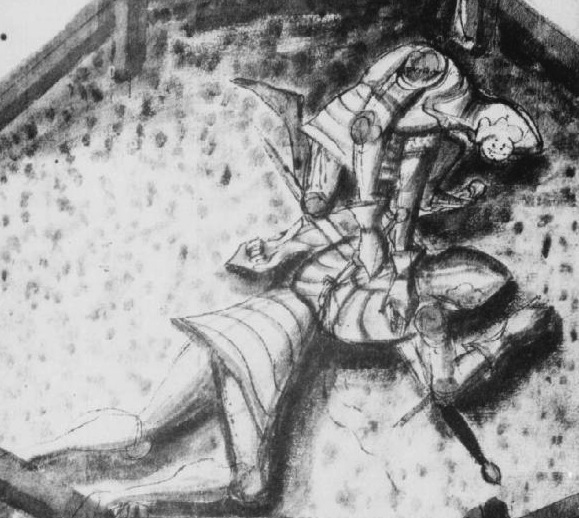

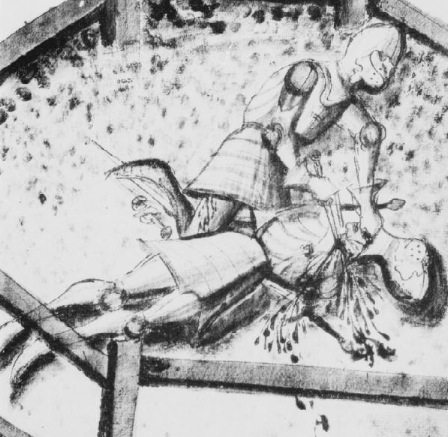

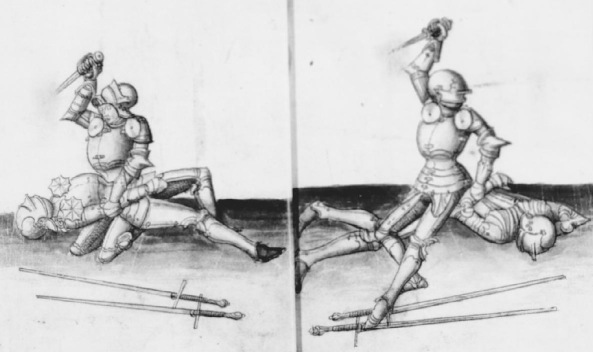

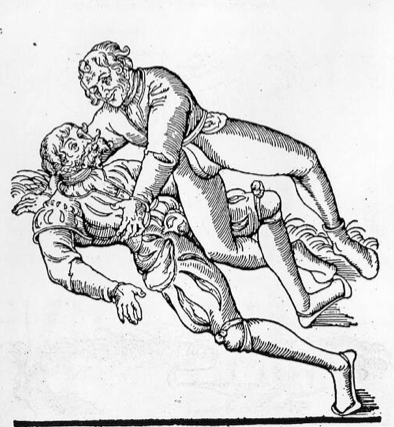

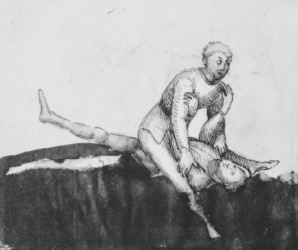

Although

my examination was not an exhaustive search, to be sure, virtually

every image of unarmed fighting techniques within Renaissance martial

arts source teachings, a combatant is displayed either being thrown

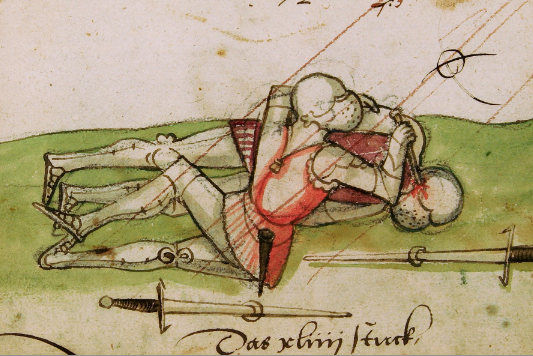

down or being held upright. Even then, most of the ground fighting images (as

the example collected here reveal) reflect restraining or mounting

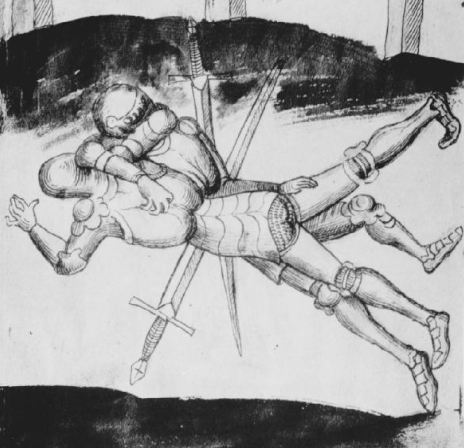

in place an opponent who has already been taken down. Excluding a few unsurprising images

of a prone figure in armor being dispatched by a dagger (such as in the

Gladiatoria and Solothurner Fechtbuchs), I have so far found noticeably

few exceptions — not counting for repetitions of the same technique appearing

again in later editions, such as the various versions of Hans Talhoffer's

work. Although

my examination was not an exhaustive search, to be sure, virtually

every image of unarmed fighting techniques within Renaissance martial

arts source teachings, a combatant is displayed either being thrown

down or being held upright. Even then, most of the ground fighting images (as

the example collected here reveal) reflect restraining or mounting

in place an opponent who has already been taken down. Excluding a few unsurprising images

of a prone figure in armor being dispatched by a dagger (such as in the

Gladiatoria and Solothurner Fechtbuchs), I have so far found noticeably

few exceptions — not counting for repetitions of the same technique appearing

again in later editions, such as the various versions of Hans Talhoffer's

work.

As has been pointed out, we do not see in the majority of the

images actual ground "fighting" (that is, the fallen opponent

successfully defending themselves or wrestling on their back),

but rather ground "killing."

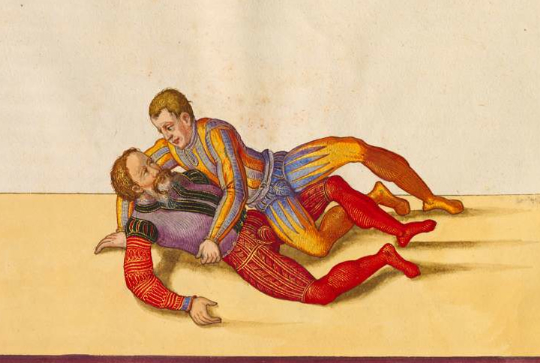

We find only a few ground techniques depicted in the early German works, showing

limb locks or pinning holds, but ground fighting is not present in the

teachings of major Masters of Defence such as Fiore De Liberi, Filippo

Vadi, Achille Marozzo, etc. What does appear makes up a tiny fraction

of the art and associated text of unarmed combat. One edition of Hans

Talhoffer's Fechtbuch depicts just one out of tens, while two other

editions have just three. Two ground fighting images appear in Leckuechner's

messer manual, one in the Codex Wallerstein, and three in an anonymous

15th century German work. Paulus Kal's work from the 1470s contains

just three. The late 15th century work by Hans Wurm, a whole manuscript

on unarmed fighting, shows not a single one. There also appears only

one sample plate in the work of Hans Lebkommer (c.1500). Out of more than

80 plates on Ringen moves in Fabian von Auerswald's 1539 book there

is only a single solitary image showing both fighters on the ground. Even

the largest collection of Ringen teachings, that of Paulus Hector Mair's

immense compendia (c.1545), has only two or three ground images out of

tens on grappling. None appear in Albrecht Duerer's unarmed techniques

either. Not a single image of ground fighting is shown in the many Ringen

plates of Joachim Meyer's famous treatise of 1570. The same can be

said of the late 17th century unarmed teachings of Nicholaes Petter.

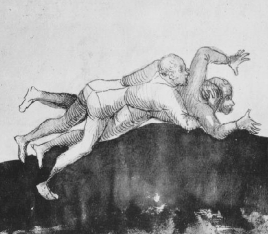

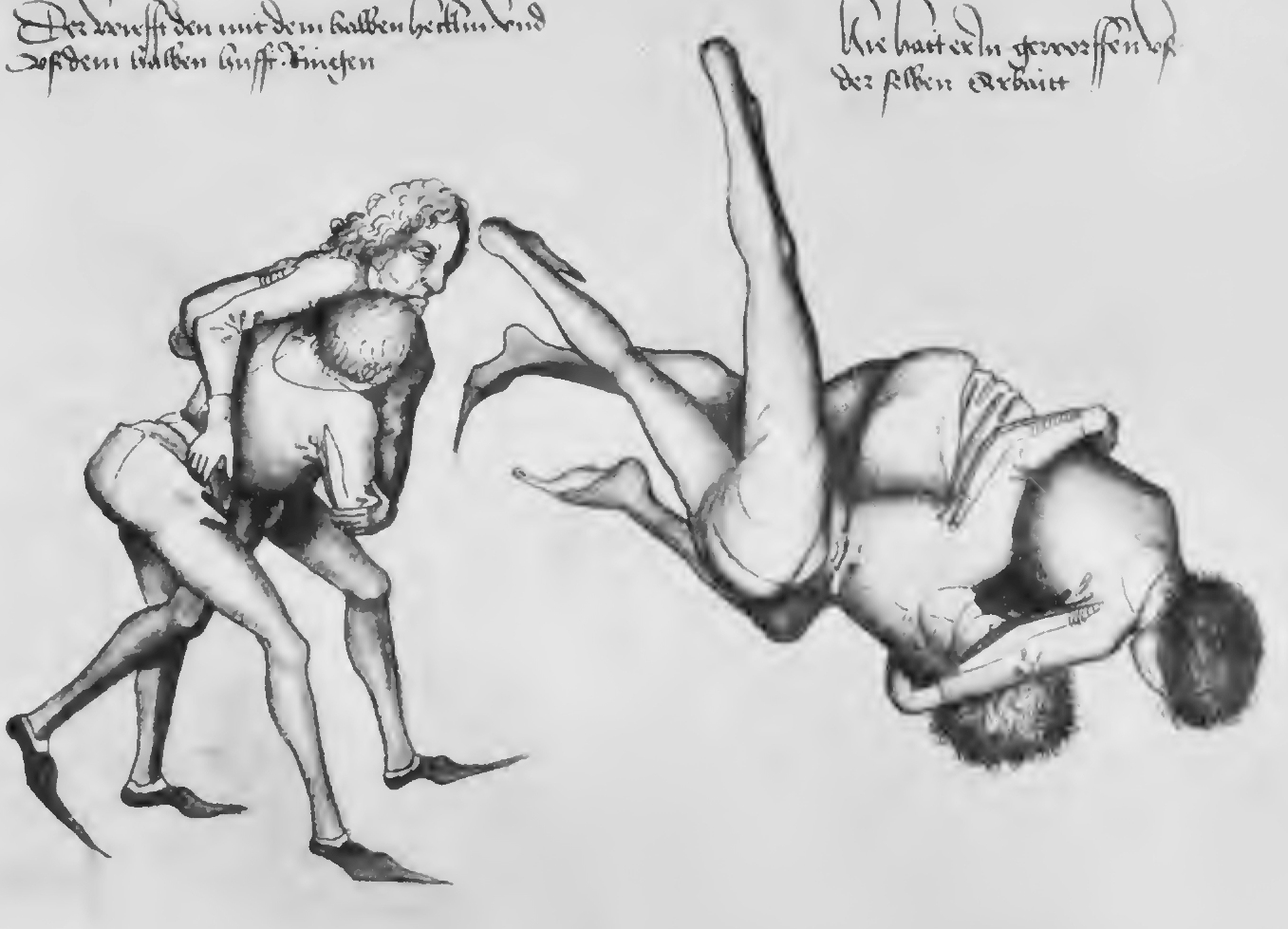

Sure

enough, the whole point of Ringen is to get your opponent down while you

remain free and upright so that you can use your weapon on him (which

is what a major portion of the illustrated armored combat sequences within

the sources ultimately end with). Or else you give yourself the chance

to escape. Those times that combatants are illustrated as being lifted

or tossed they no doubt will surely end up grounded, but this does not

mean you are supposed to then jump on them. No, rather, they are

finished as a result of the slam, and if not, then you employ your weapon

or flee. So, while the German schools of defence have the concept of Unterhalten("holding

down") as a component of wrestling, and one major Italian

source expresses a preference not to roll around on the ground but to

safely stand up and throw your man. In his fighting treatise, the

master Fiore dei Liberi wrote consistently of throwing his man to the

ground, but never of joining him there. Sure

enough, the whole point of Ringen is to get your opponent down while you

remain free and upright so that you can use your weapon on him (which

is what a major portion of the illustrated armored combat sequences within

the sources ultimately end with). Or else you give yourself the chance

to escape. Those times that combatants are illustrated as being lifted

or tossed they no doubt will surely end up grounded, but this does not

mean you are supposed to then jump on them. No, rather, they are

finished as a result of the slam, and if not, then you employ your weapon

or flee. So, while the German schools of defence have the concept of Unterhalten("holding

down") as a component of wrestling, and one major Italian

source expresses a preference not to roll around on the ground but to

safely stand up and throw your man. In his fighting treatise, the

master Fiore dei Liberi wrote consistently of throwing his man to the

ground, but never of joining him there.

We must remember, virtually everyone carried a dagger back then and often

you might be facing multiple opponents, or be encumbered by armor. The

last thing you wanted to do is grapple while laying prone where your eyes

can be gouged, your groin ripped, and the adversary maim you by biting

— you know, all the things that occur in life and death combat

situations but are omitted and forbidden in the controlled conditions

of wrestling sports and MMA. Go figure.

I

consulted with a certain former student about this and he too concurred

with the obsession for grappling among many modern self-defense methods. As

a 14-year police SWAT veteran, he noted how the last thing he wants to

do is go to the ground with a suspect where he might then become vulnerable

to a hidden weapon, as well as clawing, biting, etc., not to mention having

his own firearm taken from him. Why do it when he can instead use his

stick or employ a move that takes the person down? I

consulted with a certain former student about this and he too concurred

with the obsession for grappling among many modern self-defense methods. As

a 14-year police SWAT veteran, he noted how the last thing he wants to

do is go to the ground with a suspect where he might then become vulnerable

to a hidden weapon, as well as clawing, biting, etc., not to mention having

his own firearm taken from him. Why do it when he can instead use his

stick or employ a move that takes the person down?

Something I have observed over the last decade's emergence of historical

European martial arts study is that practitioners who come from a judo/jujutsu

or Greco-Roman wrestling background will in the middle of free-play make

a mental decision to stop fencing and start grappling. They fail to connect

the skill sets together as simply "fighting." So, they typically

get hit in that instant where they are making the mental shift between

the two. The same phenomenon occurs notoriously among classical fencers

and those who have never practiced any unarmed skills. When you close

with them and make body contact they are easily overcome because they're

still hopelessly stuck in "swordplay" mode. Watching

my students the past few years who are skilled grapplers learn the

difficulty of employing the simplest of unarmed techniques against a

skilled swordsman in fencing bouts has been illuminating.

I've

also noticed a tendency whereby too many enthusiasts approach the idea of Ringen

as just a wrestling match where they come to the clinch then try to go

straight to the ground and roll around until someone submits. The

reality of serious combat however is that a fighter should want to

avoid entanglements. When you can get the opponent off his feet while

you remain upright it's a tremendous advantage. You don't then willingly

join him there. We might recall that both Vincentio Saviolo and George

Silver each complained in the 1590s that poor rapier fencing led to the

fighters going quickly to the ground, which they each considered to be

something inferior to effective fighting. I've

also noticed a tendency whereby too many enthusiasts approach the idea of Ringen

as just a wrestling match where they come to the clinch then try to go

straight to the ground and roll around until someone submits. The

reality of serious combat however is that a fighter should want to

avoid entanglements. When you can get the opponent off his feet while

you remain upright it's a tremendous advantage. You don't then willingly

join him there. We might recall that both Vincentio Saviolo and George

Silver each complained in the 1590s that poor rapier fencing led to the

fighters going quickly to the ground, which they each considered to be

something inferior to effective fighting.

Wrestling is the basis of all fighting, as the grandmaster Liechtenauer

and the master Fiore dei Liberi both tell us. But I believe this does

not mean its techniques are the heart of the matter, but only its central

idea that whether you are armed or not the very core of all combat reduces

to closing with and leveraging the opponent. As Dr. Sydney Anglo pointed

out in his seminal work on the martial arts of Renaissance Europe, the

role of wrestling in knightly martial culture was viewed in contradictory

ways during the 14th to 16th centuries. I suspect now the issue might

have been one of the difference between Kampfringen — grappling

techniques that are about throws, take downs, disarms, and unarmed skill

versus weapons—as opposed to wrestling as a sport of going to the

ground to achieve a submission hold — something to be avoided in

a life and death encounter.

Ground

fighting without weapons in our source works is very limited — despite

the impression some practitioners now have that it was or is especially

important. And when it is present with weapons, it is in the context of

finishing off an opponent that has been taken down. That's certainly not

the kind of ground fighting people do now in mixed martial arts practice.

Thus, while it is not in dispute that there is "some" ground

fighting in the source teachings, what I am proposing is that this "some"

is actually quite small and really not all that significant. I believe

that it was uncommon and not the intended goal of Ringen training. Those

who believe differently are certainly free to provide evidence that contradicts

this view. Ground

fighting without weapons in our source works is very limited — despite

the impression some practitioners now have that it was or is especially

important. And when it is present with weapons, it is in the context of

finishing off an opponent that has been taken down. That's certainly not

the kind of ground fighting people do now in mixed martial arts practice.

Thus, while it is not in dispute that there is "some" ground

fighting in the source teachings, what I am proposing is that this "some"

is actually quite small and really not all that significant. I believe

that it was uncommon and not the intended goal of Ringen training. Those

who believe differently are certainly free to provide evidence that contradicts

this view.

I tell my students do all the grappling and wrestling you like and you

will not learn the value of fencing. But do fencing right and you will

learn the value of Ringen. For myself, I have never studied wrestling

or grappling arts. Instead, my skills and all I know about it, I have

learned from my practice of historical fencing — a craft which

I approach without any artificial post-Renaissance separation between

armed and unarmed teachings.

There

is no denying the utility and value of skills in ground fighting as being

beneficial for a martial artist. But in combat, standing up when your

opponent is on the ground is arguably superior to anything else. All

the more so when deadly weapons are involved. I believe our historical

source teachings reflect this. The only time this is not true is when

you make fighting into an unarmed contest or game where you want to force

an opponent to tap out. (If you doubt it, try wrestling sometime

against someone carrying a small dagger in their belt. See how quickly

things end.) There

is no denying the utility and value of skills in ground fighting as being

beneficial for a martial artist. But in combat, standing up when your

opponent is on the ground is arguably superior to anything else. All

the more so when deadly weapons are involved. I believe our historical

source teachings reflect this. The only time this is not true is when

you make fighting into an unarmed contest or game where you want to force

an opponent to tap out. (If you doubt it, try wrestling sometime

against someone carrying a small dagger in their belt. See how quickly

things end.)

So, we are left with no choice but to challenge those advocating ground fighting

in RMA (Renaissance martial arts) to show us the evidence, textural or

iconic, from our source teachings. Where's all the ground fighting?

October 2009

End Note: I think

ground-work as a whole is just overrated—a result of the pendulum

of modern popular martial arts having excluded grappling in favor of "kick-boxing"

styles for so long that when the Brazilians came along and wiped out fighters

in the mid-1990s everyone soon realized their deficiencies. Nowadays,

things are back where they should be for modern unarmed self-defense:

people acknowledge that you need to be able to fight standing up, to throw

or block blows when necessary, to face multiple attackers, and more importantly

to effect take downs and throws (or prevent them being used on you). When

you over emphasize ground-work because it's popular you are a less well-rounded

fighter—whether modern or historical, armed or unarmed. I think

that historical lesson has been relearned out of our recent military conflicts.

In historical fencing studies, the immediate lethality of weapons in close-combat

encounters teaches you right away to avoid purposely going to the ground

with your opponent. I think our ancestors knew this. And it's even more

so when modern firearms are involved.

|