Challenges

and Rewards Challenges

and Rewards

Translating and

Working with Sources of Mare

By David Kite

ARMA Scholar

December 2012

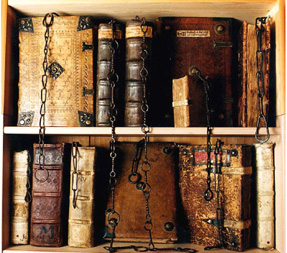

Uniquely

among the martial arts of the world, students of the martial arts of Europe

have at their disposal numerous records detailing the application of close

personal combat. These primary sources exist as both textual and pictorial

documents, and while the number of surviving sources grows beginning about

the 18th century, for our period (about 1300 to 1650 AD), they are much

more rare. However, since many of these works have become available, either

in print or online, the average practitioner has an unprecedented opportunity

to study them on their own. Working directly with these materials provides

many benefits to the martial arts student, but it also poses a number

of challenges. This essay discusses some of those challenges, as well

as illuminates some of the invaluable benefits gained from working directly

with the source material. Uniquely

among the martial arts of the world, students of the martial arts of Europe

have at their disposal numerous records detailing the application of close

personal combat. These primary sources exist as both textual and pictorial

documents, and while the number of surviving sources grows beginning about

the 18th century, for our period (about 1300 to 1650 AD), they are much

more rare. However, since many of these works have become available, either

in print or online, the average practitioner has an unprecedented opportunity

to study them on their own. Working directly with these materials provides

many benefits to the martial arts student, but it also poses a number

of challenges. This essay discusses some of those challenges, as well

as illuminates some of the invaluable benefits gained from working directly

with the source material.

Parallel to the availability of sources in general, for many years,

one of the major challenges and limitations facing the martial arts practitioner

was simply a lack of translations. Even the works originally written in

English were difficult to understand, partly due to the archaic language,

and partly due to the lack of a broader understanding of the art. Today,

a large number of manuals are available in translation, but many important

works remain untranslated. However, even available works can be difficult

to find on the web, and even modern printed editions have limited print

runs, so copies can be difficult to come by.

However, even the availability of translations presents its own challenges,

particularly when they are ambiguous or inaccurate, which becomes apparent

in the case of multiple translation of the same work. Every translation

is inherently also an interpretation, so it is important to remember that

no matter how literal or accurate a translation, it is still filtered

through the lens of the translator. As such, it is subject not only to

that individual's understanding of the art of fighting, but also the original

language, the original author's intent, as well as the translator's ability

to translate that meaning into his own language.

Translating a text is certainly no easy task. Reading often poorly legible

scripts written in archaic languages is difficult enough. However, even

when reading and understanding a text becomes fairly straightforward,

deciding how best to render it in another language so that it is both

understandable and remains faithful to the original adds quite a lot of

complexity to the process. Often, words have different meanings depending

on context, if they can even be efficiently translated at all, and when

translating, choosing one word over another can drastically alter an interpretation

or obfuscate meaning.

It is easy to assume that working with a source written in the native

language of the reader (albeit an ancient version) would mitigate these

problems, but this is not necessarily the case. Variations in spelling

is the most obvious problem encountered, but is also the most easily surmountable.

More difficult are archaic standards of syntax and grammar. English works

specifically are, in a word, verbose. The written language, in many cases,

was much closer to the spoken language than it is today, with the result

that frequently labyrinthine sentences often span the bulk of a single

page and more.1

The contents of our source materials can provide more difficult challenges.

The completeness of a work, and even the level of detail either in the

text or illustrations can have a dramatic affect on the reader's understanding.

In longer technical works, such as master Joachim Meyer's Gründtliche

Beschreibung, information and explanations of useful fighting concepts

are not always presented in complete or discrete chunks. Because most

fighting concepts are universally applicable across weapons, information

introduced in one section may be further expounded upon in one or more

later sections. As a result, it becomes important to read an entire work

in order to gain a more complete understanding of an author's teachings,

even if you are not interested in a particular weapon. This is problematic

if a work is not available in its entirety, such as Paulus Hector Mair's

manuscripts. Although scans of two of his entire treatises are available,

translations of the whole work currently are not.

Further complicating this is the fact that not all of our surviving

materials were intended to be instructional works, or include entire methods.

The "Solothurner Fechtbuch," for example, provides numerous

illustrations but no accompanying text, and seems to have been intended

as a presentation piece, much like a modern coffee table book.2 Other

works, such as MS Harley 3542 ("Man yt Wol") demonstrate somewhat

the opposite problem; that of sparse or cryptic text with no illustrations.

The 14th century verses of the master Johannes Liechtenauer could be included

here if it weren't for the fortunate survival of several copies with accompanying

glosses.

Finally, one of the most challenging, as well as potentially the most

limiting, aspects of working with the source material is how to actually

use them. These challenges and limitations can be manifest in how we view

both the text and the illustrations. Swordsmith Peter Johnsson remarked

in his lecture on Medieval sword design that a sword is a thing designed

to be in motion.3 These martial arts

are no different; they are an activity. Their texts describe motion. The

illustrations are two-dimensional static representations of three dimensional

figures in motion. It is very easy to approach these source works with

false assumptions, particularly in terms of range and timing or leverage,

and also the fluid nature of personal combat. How literally are we to

interpret this material? When we see an illustration of a figure standing

in guard facing an opponent at sword's length, should we assume we are

also to "stand in guard" at a comparable length? If we see a

technique illustrated with a certain foot position, range, or binding

at a certain point on his opponent's blade, are we to assume our application

must follow suit exactly? Or do we have room to maneuver? The same

is true of textual descriptions. When explaining a technique or fighting

concept, the authors often went beyond explaining just the technique or

concept itself, adding important but otherwise extraneous material. It

is often difficult to determine what are actually the important details

of the technique or concept itself, and what is simply an action leading

up to, or following from it.

Similarly, when two sources present a technique in similar ways but

with dissimilar details, are we to believe the authors actually had different

understandings of that technique or concept, or that the techniques are

actually different? Or were their explanations simply two different applications?

In other words, are we missing the forest for the trees? For example,

what is it exactly that makes the strike known as a Krumphau a

Krumphau, or what is the underlying concept of the duplieren

explained by Sigmund Ringeck? Can we diverge from his example technique

and still be faithful to the duplieren concept, or is the divergence

a bastardization?

Despite these difficulties, however, there are many worthwhile benefits.

Working directly with the surviving source material provides a much more

intimate understanding of these martial arts. Any historian will laud

the value of studying primary sources over secondary sources. While working

with a secondary source certainly has merit, and can provide very detailed

information about a subject, it can never be more than a study or survey.

By contrast, the primary source is the history. In working with

primary sources, we are therefore not limited to modern interpretations

of historical context. In most cases, and in varying amounts of detail,

the authors expound upon their own views and opinions. Reading primary

sources tells us exactly what the authors said, and how they understood

the art (supposing of course they were successful in clearly articulating

their meaning).4

Working with original languages has similar benefits to working with

primary sources in general. In doing so we gain a deeper understanding

of the primary source itself, as well as the author's intent and the martial

art in general, without having it filtered through the lens of a translator.

Where most secondary sources such as history books tell us about a topic,

even a translation of a primary source only gives us the translator's

interpretation of the author's meaning, as discussed above. This remains

true even when you yourself are the translator, but here there is no intermediary,

and the transmission is more direct.

Building from this, working directly with more than one source will

also deepen our understanding. As stated earlier, different sources provide

different details, and in varying quantities and qualities. By studying

more than one source, we can use one to inform our interpretation of another.

Hans Talhoffer's early 15th century fight manuscripts, for example, provide

little textual information. It is only after we have gained an understanding

of the martial arts from other, more robust, sources that we can then

appreciate what Talhoffer offers us.

Another benefit stems from the simple advantage that a written tradition

has over an oral tradition. Unlike most Asian martial arts as they are

practiced, we actually have written catalogs of our martial art. Instead

of relying solely on our own memory, or even the memory of our instructors,

we can use our source material as reference guides, which was certainly

one of their original functions. As a result, we know we are practicing

an authentic martial art. We don't need to take it on faith from someone

who must admit they also are taking it on faith. Another advantage of

this is that our art, in essence, is frozen in time. Provided, of course,

that our interpretations are correct, we know that a given element or

technique was used in a given area at a given time. We can also be reasonably

certain that the materials have not mutated or deteriorated in their effectiveness

due to the "living tradition" haunting many Asian martial arts.

While the source material does not, and cannot, provide a comprehensive

catalog of lessons, we can still be reasonably certain of what the Art

comprised.

Speaking for myself, the greatest reward is the satisfaction I get from

the study for its own sake. By working directly with the source material,

I am able to see things for myself. I am able to pursue my own course,

answer my own questions, make my own discoveries, and draw my own conclusions.

When I find myself facing the many challenges this pursuit entails, overcoming

the challenges becomes its own reward.

Notes:

1 For a demonstration

of what I mean by the difference between a spoken and written language,

try reading aloud a paragraph or two from a book (scholarly works are

especially illuminating), or even this essay, and listen to how it sounds.

Then, record a conversation between you and a friend, or just you speaking

freely about a topic, and then transcribe it exactly as spoken. The differences

should be readily apparent. This may also explain why when someone reads

a speech they have written, it often sounds stilted or incomprehensible

when compared to someone who simply speaks while giving a lecture.

2 David Lindholm refers

to these types of manuals as "books of splendor" in his article

"Das Solothurner Fechtbuch: Giving it Voice," contained

in Masters of Medieval and Renaissance Martial Arts (ed. John Clements).

He includes "certain Talhoffer" manuals and the manual of Paulus

Kal among them, and stresses that these manuals are "books first

and manuals for fighting second." He further suggests that these

manuals were commissioned as works of art and as aids to memory, as opposed

to didactic presentations.

3 This was a fascinating

lecture, is discussed on several forums, and as of this writing is available

for viewing here: http://forums.dfoggknives.com/index.php?showtopic=23706&pid=223115&st=0&#entry223115

4 Unfortunately, one

major danger with taking primary sources at their word is the issue of

copy errors, a problem which plagues both manuscripts and printed books

alike. Even copies of a book within a single print run can have substantial

variations, as errors were discovered and amended during the printing

process, and earlier copies were not always corrected.

See

Also:

Between

Canon and Art

|