Some

Observations on Engagement Posture With the Rapier

By

Brian Kirk

ARMA Houston, TX

The purpose of an engaging guard is to approach your opponent from a

position of relative coverage, a thing particularly important to thrust

fencing. With the sword alone in one hand, there tends to be less variance

in the nature of this position than in other weapon systems. In this article,

I will be discussing specifically the posture of the body, legs and feet

in these engaging guards with respect to the development of systems dealing

with the rapier in its origin and then decline.

The rapier, as a weapon, was invented sometime in the late 1400s, probably

in Spain, but it was not widespread or in common enough use to be discussed

in a dedicated manual until ~1550. In this context, the invention of a

new dedicated rapier style owes its origin to Italy during the 16th Century.

From there, the new rapier style would spread to the rest of Europe, as

other countries picked up on the popularity of the weapon, owing to its

usefulness in urban self defense and dueling, particularly among the burgeoning

middle class.

As I mentioned above, I am only interested in the posture of engagement

with the single sword, and so, with that in mind, there are a couple of

things to remember as you read this article. Firstly, the concept that

a sword alone was sufficient for your own defense was fairly rare prior

to the 1600s. Most manuals of the 1500s considered the sword and buckler,

sword and dagger, or sword and cape to be the more appropriate self defense

model. Secondly, the weapons of the 1500s tended to be better at cutting

than the later rapiers, and the amount of cutting that you would like

to able to do seems to influence your guard of engagement posture. Thirdly,

there are often multiple examples of engaging guards in these manuals,

and I am only choosing one example, if I feel like it is representative

of the master's intent. Fourth, I am not considering arm and blade position

in this analysis, even though, theoretically, they both influence body

posture. I have to draw the line somewhere in order to make a fair comparison,

and as long as the fighters are in a point forward position, I am basically

saying they are "close enough." Fifth, it should also be noted

that once swords are depicted as being in contact with one another, a

great many of the posture differences fall away showing that once engaged,

the requirements of combat shift to a more universal truth. Lastly, my

hypothesis presents a line of evidence which seems to promote a mostly

linear development of the postures I am presenting, but we know that history

doesn't actually work like this and that these developments would have

actually been highly regional at times. Additionally, keep in mind that

the individual manuals are not necessarily responses to all of the other

manuals, so the amount that any given master was even aware of what other

people were advocating cannot be assumed.

We cannot begin our discussion of the rapier without first considering

the origin of systematized presentation of weapon combat in Europe, the

longsword. As shown below, in the guard of Posta Breve, the basis of most

engagement postures in the longsword is: The front leg is bent while the

back leg is straight.

Fiore, Italian - 1404

Fiore, shown above, represents the oldest illustrated longsword manual,

but this posture convention is maintained throughout the entirety of longsword

use. For a more dramatic and obvious demonstration of the same posture,

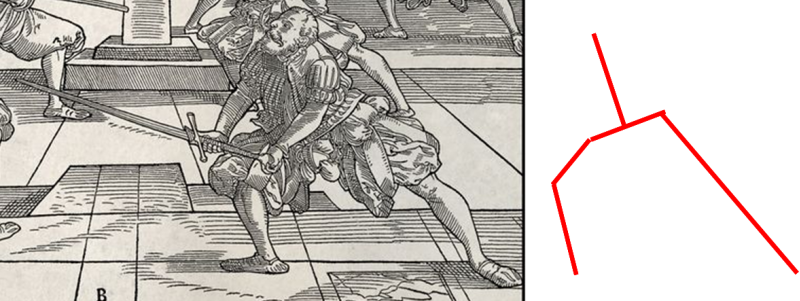

we can look to Meyer in 1570 and show the basic configuration of his legs,

hips, and spine in the accompanying stick figure.

Meyer, German - 1570

Consequently, it must be remembered that there was a strong tradition

of this longsword posture happening at the same time as the rapier system

was being developed. This same type of posture was maintained by the first

example of single sword that we have (as a dedicated subject for a fight

manual), Leckuchner in 1486, where we see the left foot in front, for

passing footwork reasons, and the body leaning forward over the lead leg.

Interestingly, here we see a very open and wide stance.

Leckuchner, German - 1486

We see remnants of left foot forward theory, even with thrusting swords,

for the subsequent 100 years or so. For example Henry St. Didier's French

single sword manual of 1573 contains mostly left foot forward engaging

guards and passing footwork.

Didier, French - 1573

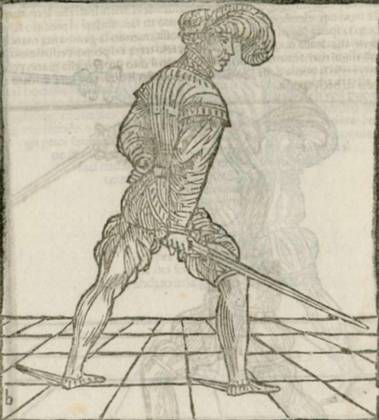

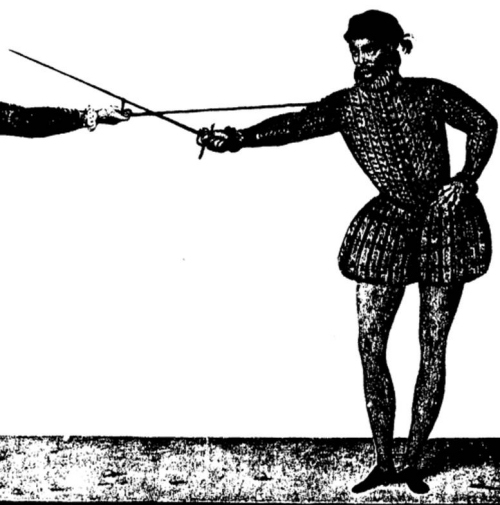

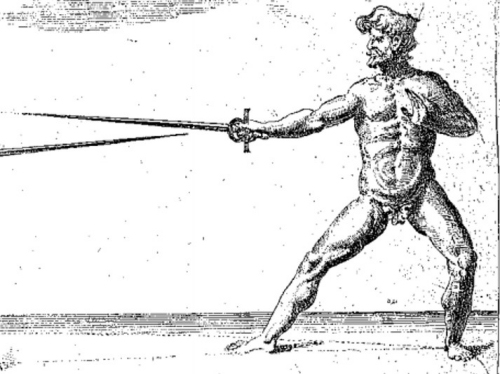

However, by the early 1500s we see the first examples of a primarily

right foot forward guard posture in the Bolognese master Marozzo, in 1536.

In this case the right foot may be forward, but the posture is still very

much the front leg is bent while the back leg is straight:

Marozzo, Italian - 1536

Marozzo and the other Bolognese masters put forth right foot forward

guards quite often, but on the whole, they still advocate mostly passing

footwork.

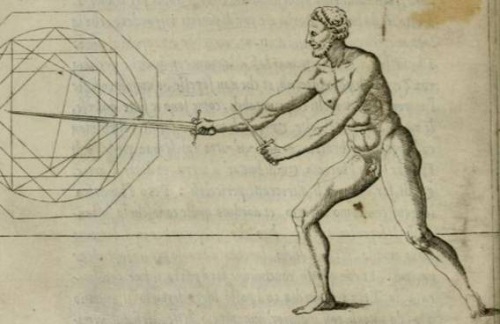

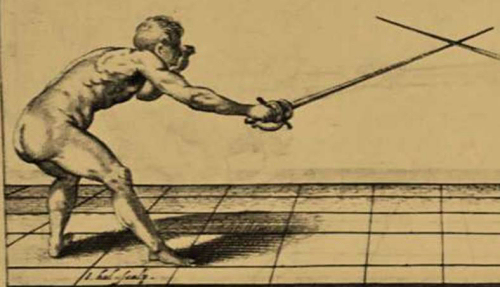

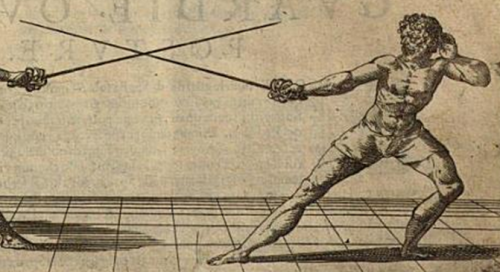

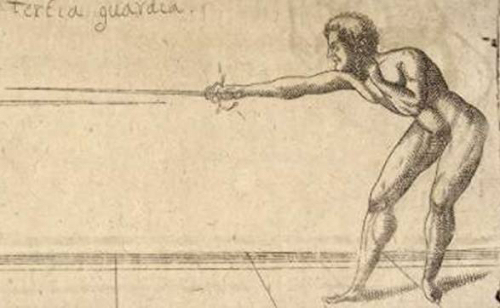

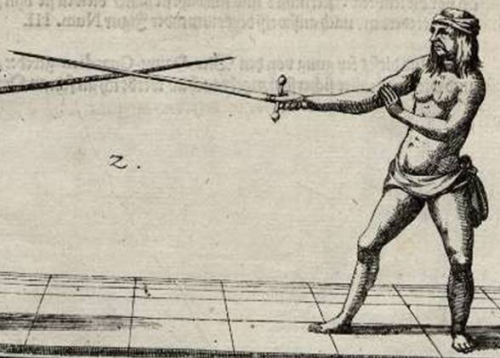

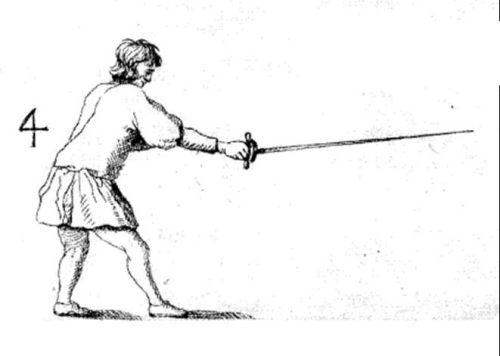

Even with Agrippa and his presentation of the first true thrust-only

manual in 1553, we see the same trend for his tertia guard.

Agrippa, Italian - 1553

(ignore the dagger)

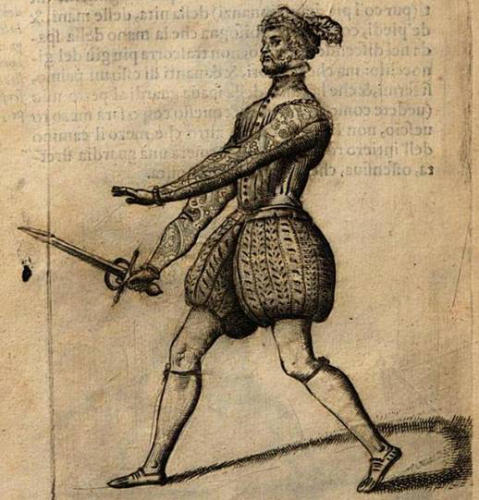

Marozzo and the Bolognese school were quite influential in the later

part of the 1500s, and so it makes sense to see both Mair and Meyer maintaining

this same posture in their presentation of the rapier in ~1540 and 1570

respectively.

Mair, German - 1542

Meyer, German - 1570

During the later part of the 1500s we do see some beginnings of a shift

in fighting theory with respect to a single sword. In Italy there were

a series of masters who explored alternative guard postures. Most famous

of these would probably be Di Grassi, who also in 1570, advocated a much

more upright posture with the feet much closer together.

Di Grassi, Italian - 1570

And Vizziani in 1567:

Vizziani, Italian - 1567

Additionally we see Lovino in 1580 also support an upright posture with

the feet close together.

Lovino, Italian - 1580

The Vizziani and Di Grassi represent good intermediates to what would

eventually become fully established as the most prevalent posture of the

1600s, as does Saviolo in 1595.

Saviolo, English - 1595

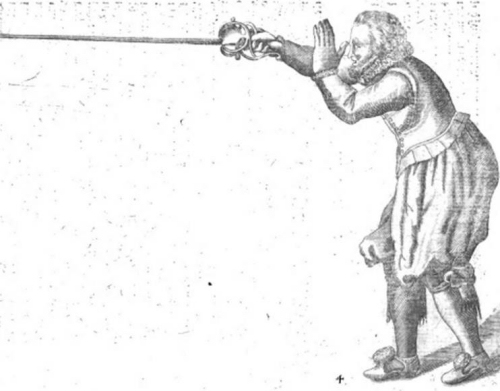

Heredia, a Spaniard in 1599, then puts forth an engaging posture that

is also very upright, like Di Grassi and Saviolo, but adds a straight

front leg, which would seem to be one of the first depictions for this

configuration.

Heredia, Spanish - 1599

Lastly, during this time, the Spanish Destreza theory was being developed.

It too featured a very upright posture as shown by Narvaez in 1599.

Narvaez, Spanish - 1599

Taken together, we can more or less think of this later part of the 1500s

as being the "Upright Fencing Era".

However, even during this period there were still some hold outs to the

older posture, as evidenced by Cavalcabo manual from 1597.

Cavalcabo, Italian - 1597

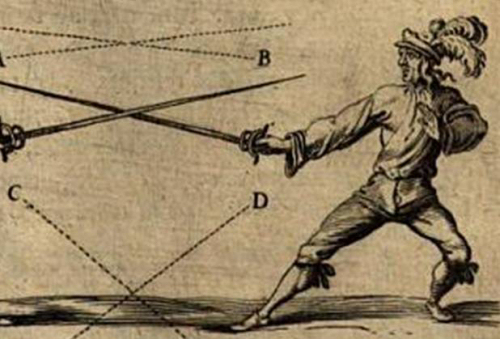

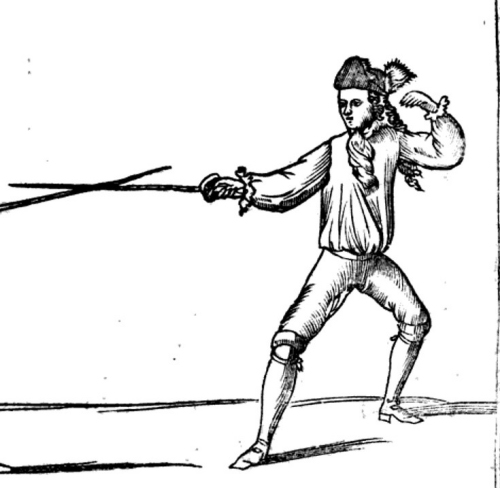

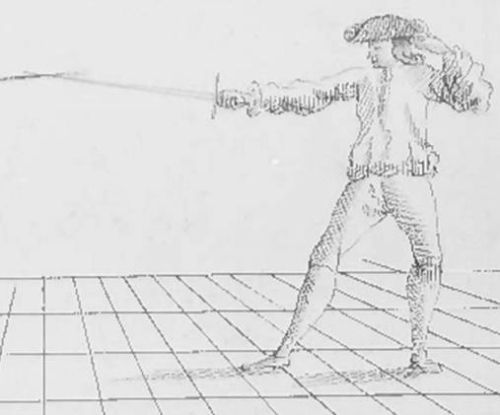

However, in the first decade of the 1600s, two manuals would arrive that

would produce lasting change for the rest of the 1600s. Whether or not

this was a reaction to the upright posture that I just described is difficult

to address, but Fabris and Giganti both in 1606 produced two new and different

postures, shown below.

Fabris, Italian - 1606

Giganti, Italian - 1606

In these new postures, the forward leg is fairly straight, like that

introduced by Heredia, but now the body posture is quite different, either

with a strong forward body lean with Fabris, or a backwards lean with

Giganti. Giganti, it should be noted, also completely opens up his foot

on his back leg. This one aspect will not be as featured in subsequent

depictions, as a more perpendicular foot placement is subsequently commonly

advised.

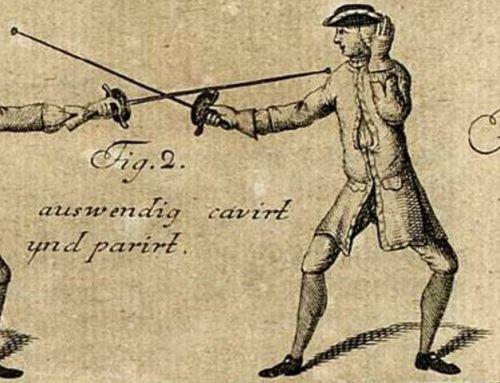

These two postures would thus spread throughout Europe as evidenced by

the following:

Huessler, German - 1615 (Fabris style)

Von Dietz, German - 1620 (Fabris style)

Alfieri, Italian - 1640 (Giganti style)

L'Ange, German - 1664 (Giganti style)

Pallavicini, Italian - 1670 (compromised style, i.e., somewhere in between

the two)

Villardita, Italian - 1670 (Giganti style)

Bruchius, Dutch - 1671 (Fabris Style)

Marcelli, Italian - 1686 (Giganti style)

Bondi, Italian - 1696 (compromised style)

D'Alessandro, Italian - 1723 (Giganti style)

We do see some alternatives to this:

Koppe, German - 1619

Koppe, shown above, looks very close to Vizziani in that he seems to

have the double leg forward bend. It should also be noted that Koppe shows

several face level guards, and all of these have the more bent posture

of Fabris.

Koppe, German - 1619

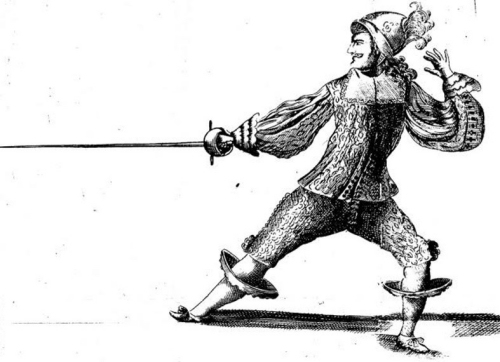

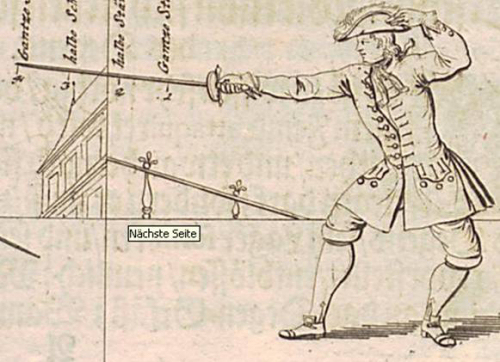

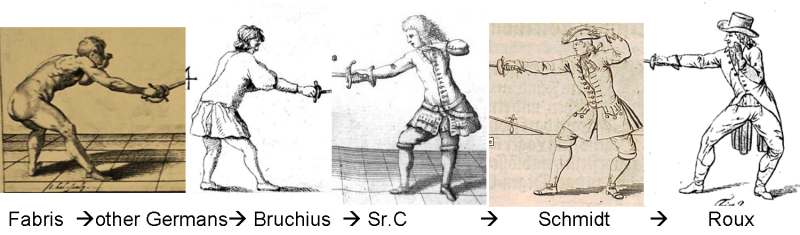

However, by 1700, we see a new variant, the smallsword posture which

will dominate fencing for the next 100 years. The smallsword variant is

from a direct line of the rapier line, it is just subtler. There is less

backward lean in the guys who lean back, and less forward lean in the

guys that lean forward. We also get an almost universal shift in where

the left hand is placed, as shown below.

Touche, French - 1670

Liancour, French - 1686

Porath, Swedish - 1693

Schmidt, German - 1713

Sr C, German - 1715

Doyle, German - 1715

Blackwell, English - 1730

Weischner, German - 1731

Eich, German - 1731

L'Abbat, French - 1734

Kahn, German - 1739

Gerard, French - 1740

Le Perche, French - 1740

Angelo, English - 1763

Roux, German - 1798

There are more smallsword manuals of the 1700s than the above list, but

for the purposes of this article, I have shown enough of them above to

see the general trends in place.

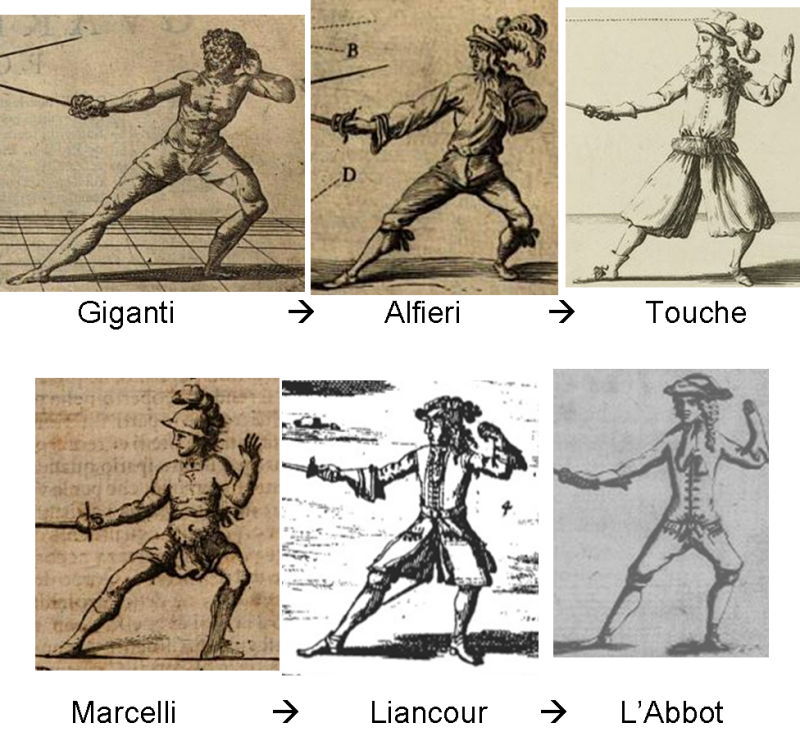

From this, an interesting observation is how the French smallsword of

Touche, Liancour, L'Abbot, and Le Perche all seem to take on the posture

that originates from Giganti and the later Italians. In contrast, some

of the German smallsworders such as Sr.C, Schmidt, and Roux seem to continue

the Fabris line seemingly through Bruchius.

Italian to French progression in time (backward body lean tradition):

Italian to German progression in time (forward body lean tradition):

Actually establishing causality in this hypothesis is difficult, as there

are lots of offshoots to each branch, but there are definitely some interesting

observations which support this. Firstly, Giganti's work was translated

into French [1], and Fabris' manual was extremely popular in German speaking

lands, with authorized or unauthorized publications dating into the 1700s.

Second, it is thought that Schmidt may have studied under Bruchius, [2]

(while Bruchius directly references Fabris as an influence) or been otherwise

directly influenced by his work, and Roux's content also contains several

bits of direct lineage evidence including the use of Caminiren, which

is quite particular to Fabris tradition manuals. We also know that French

masters of the earliest order seem to have been trained in Italy.

Finally, the above analysis does not really account for any particular

techniques or strategies advocated by these masters, as honestly, the

vast majority of the content of these manuals is so similar as to make

any slight differences irrelevant and probably a matter of personal preference.

The only conclusion that I am proposing here is that in the area of body

posture at engagement there seems to have been four main approaches: front

leg bent & back leg straight, upright, forward body lean (hollow stomach),

and backwards lean, these last two making their first appearance in the

same year (1606) by two Italians (Giganti and Fabris), and these two men

would seem to have had long lasting influence on the postures at engagement

for fighters over the next 100-200 years. The same might also be said

of the upright Destreza posture, which also had a good 200 year run; it

just seems to have had less success throughout the entirety of Europe.

Furthermore, I find it interesting how little Fabris seems to have influenced

Italian fencing in Italy. We see zero evidence that his postures were

followed by successive masters, and while he usually receives credit for

introducing the four hand turn guard system that would become standard

everywhere, the other large part of his work, the Proceeding with Resolution

(Caminiren) section is not featured in other Italian sources, as so much

as I am I aware.

One last note about the forward body lean posture is that it actively

promotes an easier passing step by having the left hip more forward than

the backwards lean posture. This makes sense, as Fabris line sources often

contain Caminiren, as mentioned above, and this requires much more passing

than most backwards lean manuals would prescribe, particularly at the

onset. This inclusion of Caminiren, even when occasionally the vast majority

of the manual is about more traditional fencing, is interesting because

it gives you increased mobility at the expense of often squaring your

shoulders more to your adversary, something that we can see the backwards

leaning people to be actively avoiding. How much giving more profile to

your opponent matters is largely related to how comfortable you are using

your own left hand for defense. The less you use your left hand, the more

the backwards lean posture probably fits what your fencing goals are,

and this is probably why it is ultimately more common than the forward

leaning posture.

Additionally, when considering different postures, an interesting observation

is made when we look at many of the French smallsword manuals. These often

like to make comments about how other nations' fencers fight. What is

odd is that almost none of the quite extensive list I have provided above

suggests that Italians stand in any way particularly different from the

French. This makes me wonder if all of those French comments are just

propaganda, owing from a little bit of an inferiority complex that all

of their fencing is actually Italian in origin; or if there was just a

whole other type of fencer who used this other posture, and they just

never really got around to writing any manuals about it. The same can

also be said of the French comments on the Germans as well, although somewhat

weirdly their descriptions of the Spanish seem to be slightly more accurate.

Liancour, French - 1686 - "Italian Guard"

The only figure from any of the Italian images that I have presented

above that even remotely looks like this is Bondi, and he is from after

Liancour, although not by much (1696 vs 1686). In fact, to my eye, something

like the later Frenchman Girard looks more like the above Liancour posture

than any of the Italians.

In conclusion, the use of an "engaging guard" is fairly central

to how single-handed thrusting swords are described throughout the literature

of the later parts of the 1500s all the way through to the 1800s. It is

almost always the first article addressed within these fighting manuals.

As such, it reflects a relative constant from which to judge fencing trends

across nations, as most of the actual sword techniques themselves are

pretty standardized by this point. From this analysis, it is my assertion

that the two Italians, Fabris and Giganti, were both successful and wide

spread enough with their publications to almost single handedly be the

source of engagement posture throughout Europe for the next 200 years.

We also see that this trend appears to have been the result in an overall

shift in the late 1500s away from the forward leaning legacy of the older

fighting lineages. Functionally this makes sense as a more loaded back

leg facilitates the lunging thrust that most of these later masters were

advocating, while the older posture better facilitates cutting through

passing footwork.

1. The French book: Croiser le fer: violence et culture

de l'épée dans la France moderne, 2002, Pascal Brioist,

Hervé Drévillon, Pierre Serna. also noted the seeming relationship

between the posture of Touche and Giganti.

2. Schmidt was in Amsterdam at the same time as Bruchius (http://fechtgeschichte.blogspot.de/2011/10/der-fecht-und-exercitienmeister-johann.html)

and contains recognizable Bruchius terminology and content. The linked

article references an 1808 lexicon which has an entry for Schmidt and

his connection to Bruchius.

|