Meditatio

et Contemplatio Meditatio

et Contemplatio

The Role of Personal Self-Reflection in the Study of Renaissance Martial

Arts

By John Clements

...Man muss fleissig nachdencken

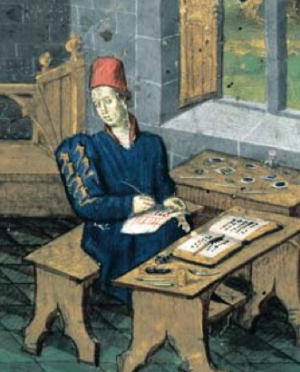

The above words ("You must study this diligently") appear in

several 15th century Germanic martial arts treatises. They express how

the student of the art of fighting must dwell upon the meaning and principles

of the passage in question. Beyond an invocation to deeply ponder and

analyze the technical aspect of each instructed concept or action, another

meaning can be proposed: The student is to internalize the larger personal

value of the self-defense teachings though self-reflection, introspection,

and solitary consideration. In other words, to utilize the familiar Medieval

tradition of quiet contemplation through meditation.

I have been employing this practice in my own study of Renaissance martial

arts for well over a decade now. I can attest to its value in improving

my prowess and my understanding of the source material of the martial

arts of Renaissance Europe ("Mare"). In this regard, I have

been following a course of action that the idea of deeply pondering the

meaning of passages from the source teachings as suggested can mean to

contemplate them through meditation, a practice that was itself a part

of the culture in which the schools and masters of defense existed.

As soon as meditation is mentioned there is the almost immediate association

of it with having to do with Eastern transcendentalism or Asian religious

beliefs. If meditation is cited in reference to Medieval civilization,

by contrast, then it also associated entirely and exclusively with the

early church. However, virtually every high-performing athlete and serious

fighter conducts some form of this activity whether or not they identify

it as such. From the sports competitor clearing his head before an event

to the boxer looking himself in the mirror to psych himself up before

training or afterwords come to terms with his progress, these are all

forms of mediation.

To

be practical and effective, any course of introspection and self-examination

has to be in a context of concrete martial reality, free from self-delusion

or new age wishful thinking.

No one today can seriously doubt the mind/body connection in which our

attitudes and emotions affect our physical performance and health. To

be practical and effective, any course of introspection and self-examination

has to be in a context of concrete martial reality, free from self-delusion

or new age wishful thinking. The question before us then becomes: is it

viable and authentic to read into the source teachings a meaning to privately

deliberate internally upon matters? This question may be unanswerable.

But for myself, I am convinced doing so has had significant impact on

my skill development.

To understand this, the reader must first break free of any preconceived

notion of "meditation" as associated with Eastern religion and

Asiatic conceptions of the word so closely connected to oriental culture

and presupposed to be inseparable from the pursuit of various traditional

martial disciplines. To study the martial arts of the "West"

it is first necessary, after all, to know what "Western civilization"

is and why it came to be.

Meditatio?

The word meditation itself is said to come from the Latin word meditārī,

which can mean to reflect on, to study, and to practice. To meditate is

itself from the Latin, meditatio, originally meaning every kind

of physical or intellectual exercise, but later coming to mean directed

contemplation (contemplationem). That is, attentive consideration

as a mental exercise, as disciplined concentration and observation, as

well as inner visualization of a matter. For example, medieval Christian

tradition might cite scriptural examples such as, "Do not let this

Book of the Law depart from your mouth; meditate on it day and night,

so that you may be careful to do everything written in it, then you will

be prosperous and successful" (Joshua 1:8). Even then, the term was

not used to describe a strictly prayerful or specifically monastic activity.

Note

I am neither advocating nor address any spiritual matters here, only those

of the psyche as related to development of personal prowess in combat

arts.

Note I am neither advocating nor address any spiritual matters here,

only those of the psyche as related to development of personal prowess

in combat arts. It is not my point here at all to reference the activity

of meditation upon Biblical scripture as part of medieval monastic practices

or Christian devotional doctrines. Neither have I found evidence this

directly influenced the teachings of the masters of defense, but it cannot

be denied that the historical masters we study existed within and were

products of the civilization and culture of Western Christendom, and that

careful, measured, thought upon ideas were a historical part of this.

To meditate upon something is to think something over and, by extension,

to find intention and preparation. This idea of personal reflection and

interpretation as understood by Medieval European civilization is largely

traceable to 3rd century Christianity, coming to later be formalized in

such disciplines as the 12th Benedictine monastic concept of Lectio

Divina. It ultimately is an effort at self-knowledge. Biblical references

to meditate and meditation abound, and essentially refer to giving careful

consideration to matters of import and value, not for theological reflection,

but personal identification --in other words, processing and internalizing

them through contemplative thought. It is reasonable to suppose this concept

was understood by other disciplines in the Medieval and Renaissance eras,

including knights and men-at-arms (who often retired to monasteries, and

in at least one late 13th century case, even produced a Fechtbuch).

There is a longstanding monastic tradition in Christendom of meditation

on the Divine as distinct from the role of meditation in Eastern religions

or Asian martial arts practices, and the two should neither be equated

nor confused. Nonetheless, the neurological and psychological basis of

the human psyche is the same everywhere, and we should not be surprised

that professional warriors and fighting men in different cultures throughout

history have found similar needs to mentally recharge, emotionally detox,

and spiritually or morally fortify themselves through similar efforts.

Whether

by communion with a higher power or through pure introspection independent

of metaphysical assumption, warriors throughout history have invoked forms

of internal dialogue or external group ritual to process their sense of

self and their identity or role as fighting men.

Whether

by communion with a higher power or through pure introspection independent

of metaphysical assumption, warriors throughout history have invoked forms

of internal dialogue or external group ritual to process their sense of

self and their identity or role as fighting men. The scene of a knightly

candidate on vigil... awake, stationary, silent, peaceful, mentally and

emotionally focused upon the beliefs that sustain him in his upcoming

ordeal... is a familiar concept within chivalric literature. It was a

feature directly borrowed from monastic culture. Whether

by communion with a higher power or through pure introspection independent

of metaphysical assumption, warriors throughout history have invoked forms

of internal dialogue or external group ritual to process their sense of

self and their identity or role as fighting men. The scene of a knightly

candidate on vigil... awake, stationary, silent, peaceful, mentally and

emotionally focused upon the beliefs that sustain him in his upcoming

ordeal... is a familiar concept within chivalric literature. It was a

feature directly borrowed from monastic culture.

The largely ceremonial meditation of the knightly vigil was essentially

for purposes of piety and contemplation of one's sins, having little to

directly do with the physical or mental preparation needed for either

immediate or long term martial prowess. And yet, it is reflective of more

than just theological devotion or cultural ritual. It might be easy for

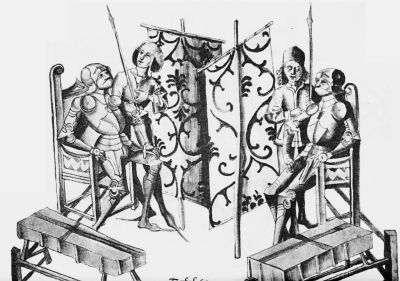

many moderns to dismiss the idea of a man-at-arms training for a judicial

duel attending daily mass before beginning each day's martial practice,

or that his fight master would take the fighter to church to pray for

victory just before the event (such as advocated in the 15th century combat

works of Hans Talhoffer). However, for the fighting men of Medieval and

Renaissance society, such piety (and ritual) served a practical function

of helping provide a sense of righteous tranquility and consolation. It

achieved this partly through its role of enabling a more focused emotional

and mental state. In the same way, the solitary moments of a lone combatant

spent in devotion or prayer in the hours before a judicial duel, the group

mass held for troops before a battle, or the man-at-arms seeking confession

prior to fighting, may all be seen as examples of this. Knightly orders

such as the Templars famously united their martial and religious training,

tying each discipline together through their common practices, which presumably

meant some effort spent at contemplation.

What

this is about is simple mindfulness...that quality or

state of

being conscious and aware of some matter. Such a mental state is

about

focusing awareness in the moment yet calmly acknowledging and

accepting

one's thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations.

Recorded as early as 1530 by the English court scholar & priest,

John Palsgrave, myndfulness was a translation of the French pensee ("thought" or "careful consideration").

What this is about is simple mindfulness... that quality or state

of being conscious and aware of some matter. Such a mental state is about

focusing awareness in the moment yet calmly acknowledging and accepting

one's thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations. The value of this for

progress in a fighting discipline should be obvious. It can also make

use of the non-cognitive and subconscious aspects of our psyche, yet it

contrasts with the Eastern approach of seeking clarity through non-conscious

non-self-awareness.

The

teachings of the martial arts of Renaissance Europe essentially present

a coherent view of the physical aspects of self-defense disentangled from

metaphysics or theology, but they are not lacking in addressing the emotional,

ethical, and spiritual concerns of the fighting man.

The teachings of the martial arts of Renaissance Europe essentially present

a coherent view of the physical aspects of self-defense disentangled from

metaphysics or theology, but they are not lacking in addressing the emotional,

ethical, and spiritual concerns of the fighting man. The possibility that

the practice and study of combat teachings may go beyond a purely intellectual

or analytical reading of self-defense instructions, toward reaching an

inner meaning for the practitioner is arguably intrinsic to all high-level

martial disciplines, for these skills do not function on a purely physical

level alone, but involve the totality of the self. This then, is the occidental

concept of meditation under examination here.

Contrasts Between West and East

On occasion, I still encounter followers of traditional Asian fighting

disciplines who will assert the narrow-mindedness that the historical

European combatives we follow are somehow not "true" martial

arts because they "lack the element of meditation." Aside from

the ethnocentrism of this view, it's profoundly ignorant to assume that

for it to be legitimate, meditation must be a requirement of any systematic

self-defense method. My response to such opinions has been to ask the

questioner what they mean by the word "meditation," then following

their reply to next ask if they are in fact referring to the Western idea

of meditatio as in Medieval monastic practice? The reaction is

to typically leave them dumbfounded. It is their prejudice that causes

them to assume our craft doesn't have meditation and their prejudice that

assumes all personal contemplation must all equate to their conceptualizations.

The

possibility that the practice and study of combat teachings may go beyond

a purely intellectual or analytical reading of self-defense instructions,

toward reaching an inner meaning for the practitioner is arguably intrinsic

to all high-level martial disciplines, for these skills do not function

on a purely physical level alone, but involve the totality of the self.

Meditation is an issue frequently mentioned in reference to spirituality

or transcendence within the martial arts. In East Asian traditions, meditation

is linked to the ideal that "normal consciousness" obscures

the "sacred" and that rational patterns of thought must be extinguished

in order to achieve a supposedly "higher" or "altered"

state of consciousness "necessary" to find "enlightenment"

in Buddhist belief. These traditions typically emphasize meditation with

associated breathing exercises. Today, this is regularly presented in

some form or another to Asian martial arts students in the West, often

as little more than a means of lending an air of "oriental mystique"

to self-defense practices.

As

martial arts anthropologist, Professor Tom Green, has described: "Meditation

is the general term for various techniques and practices designed to induce

an altered state of consciousness, develop concentration and wisdom, and

relieve stress and induce relaxation. On the simplest levels it is utilized

to calm, cleanse, and relax the mind and body and to increase concentration

and mental focus. On higher levels, it is practiced to produce a radical

transformation of the character. Meditation is really mind/body training

that is learned through discipline and practice." (Green, p. 335)

Of course, recourse to mystical concepts such as cultivation of chi

or ki is a core aspect of many Asian meditative systems and has

been famously influential in the development of their traditional fighting

systems. As Professor Green notes: "Today in the United States, the

majority of books, articles, and advertisements dealing with the martial

arts at least pay lip service to the idea that some kind of 'self control'

or 'mental discipline' is a byproduct of the training... In many classes,

meditation is defined as a few short seconds at the beginning of a class...

or perhaps for marketing purposes, to lend a vague flavor of Eastern culture

and mystery." (Green, p. 337) We might add that this phenomenon is

hardly exclusive to the pursuit of traditional Asian martial arts within

the USA alone, but is found worldwide. Green describes meditation within

Asian fighting disciplines as having to do with "psychophysical self-cultivation,"

noting: "The Asian martial arts grew up intertwined with Daoism

(Taoism), Shintô, Buddhism, and other magico-religious traditions

that emphasize meditation as a means of gaining some form of enlightenment.

It is no surprise that the traditional martial arts include meditation

as either an integral part of or an adjunct to training. The classic martial

arts have a long history in Japan, China, and elsewhere of using meditative

practices as instruments of 'spiritual forging.'" (Green, p. 335) As

martial arts anthropologist, Professor Tom Green, has described: "Meditation

is the general term for various techniques and practices designed to induce

an altered state of consciousness, develop concentration and wisdom, and

relieve stress and induce relaxation. On the simplest levels it is utilized

to calm, cleanse, and relax the mind and body and to increase concentration

and mental focus. On higher levels, it is practiced to produce a radical

transformation of the character. Meditation is really mind/body training

that is learned through discipline and practice." (Green, p. 335)

Of course, recourse to mystical concepts such as cultivation of chi

or ki is a core aspect of many Asian meditative systems and has

been famously influential in the development of their traditional fighting

systems. As Professor Green notes: "Today in the United States, the

majority of books, articles, and advertisements dealing with the martial

arts at least pay lip service to the idea that some kind of 'self control'

or 'mental discipline' is a byproduct of the training... In many classes,

meditation is defined as a few short seconds at the beginning of a class...

or perhaps for marketing purposes, to lend a vague flavor of Eastern culture

and mystery." (Green, p. 337) We might add that this phenomenon is

hardly exclusive to the pursuit of traditional Asian martial arts within

the USA alone, but is found worldwide. Green describes meditation within

Asian fighting disciplines as having to do with "psychophysical self-cultivation,"

noting: "The Asian martial arts grew up intertwined with Daoism

(Taoism), Shintô, Buddhism, and other magico-religious traditions

that emphasize meditation as a means of gaining some form of enlightenment.

It is no surprise that the traditional martial arts include meditation

as either an integral part of or an adjunct to training. The classic martial

arts have a long history in Japan, China, and elsewhere of using meditative

practices as instruments of 'spiritual forging.'" (Green, p. 335)

In

the Medieval European traditions, meditatio was a general term

for contemplative theological or philosophical discourse or devotional

exercises which lead to intuitive insight and rational wisdom.

In the Medieval European traditions, meditatio was a general term

for contemplative theological or philosophical discourse or devotional

exercises which lead to intuitive insight and rational wisdom. Medieval

theologians were well aware of Biblical instructions to "meditate"

upon the gospels, and many monastic orders practiced some form of meditative

activity. Besides prayer, the Christian was also instructed by his scripture

to engage in mental reflection and practice contemplative thought (for

example: "brethren, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever

is right, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is of good repute,

if there is any excellence and if anything worthy of praise, dwell on

these things" Philippians 4:8). The major distinction to contrast

Western from Eastern conceptions perhaps lies in Western culture's emphasis

on empirical rationalism through deliberative thought and conscious introspection,

as opposed to intuitive non-cognitive metaphysical insight.

In each civilization however, East or West, the mental discipline of

such "psychophysical self-cultivation" results in improved relaxation,

self-control, and concentration, all of which promote health and thus

can lead to better a physical disposition which then inspires martial

skill.

Premeditatio and Gymnasia

The idea of premeditatio, meaning both preparation and

meditation, refers to the consideration and deliberation on tasks or

events that lie ahead. Premeditation was a hallmark of the Greek Stoics

and has its origins among, not surprisingly, the Pythagoreans, who

influence is found in the works of 16th century fencing masters. The

morning exercise of preparing yourself by mentally rehearsing what the

day ahead held in order to face it calmly and without distress, was then

followed by gymnasia, or practical training. The idea of premeditatio

is found prominently in the writings of Cicero, Marcus Aurelius,

Cicero, and Seneca, among other noted Romans (reintroduced to the church

by Petrarch in the 15th century). For the Stoics, the exercise was said

to be the idea of employing one's intellect to rationally meditate upon

affirmations and maxims in anticipation of a future event, considering

especially the worst case scenario (premeditatio mallorum).

This philosophical practice of mental preparation for adversity would

in modern psychology be viewed as simple mental tools that function to

reduce fear and anxiety. We can now more easily understand how,

through the influence of classical sources on Christendom, Medieval and

Renaissance fighting men would have been able to adapt some of these

ideas as their own. That chivalric literature was greatly concerned with

matters of how a knight dealt with how his personal failings affected

hi ability to maintain his oaths and uphold his virtues as well as

achieve prowess and renown, is well known matter.

Forging a Personal Relationship to the Modern Practice of the Source

Teachings

In

my own personal pursuit and practice of Mare (the martial arts of Renaissance

Europe), over the years I have consciously endeavored to avoid at every

possible opportunity any potential element of cross-pollination or contamination

with material outside of the authentic source teachings of our craft.

Only when I have found aspects that are credibly identifiable as indigenous

to our source teachings have I then allowed myself to look at similar

elements in other world martial culture for clues to those universal commonalities.

In doing this, one area that has slowly coalesced for me was discovering

the value of quiet, directed contemplation and self-reflection. Because

of the personal nature of such exercise, its esoteric component and close

connection to ethical values and individual convictions, it's a difficult

subject to breach to even the closest students or colleagues. In

my own personal pursuit and practice of Mare (the martial arts of Renaissance

Europe), over the years I have consciously endeavored to avoid at every

possible opportunity any potential element of cross-pollination or contamination

with material outside of the authentic source teachings of our craft.

Only when I have found aspects that are credibly identifiable as indigenous

to our source teachings have I then allowed myself to look at similar

elements in other world martial culture for clues to those universal commonalities.

In doing this, one area that has slowly coalesced for me was discovering

the value of quiet, directed contemplation and self-reflection. Because

of the personal nature of such exercise, its esoteric component and close

connection to ethical values and individual convictions, it's a difficult

subject to breach to even the closest students or colleagues.

Yet, I have come to find that as my prowess in these skills matured,

as my interest in understanding the nature of these violent historical

practices evolved, I came to find myself more and more discovering peace

of mind in meditatio --exactly that moment of quiet contemplation

and self-reflection upon the motives, objectives, goals, and reasons for

pursuing my interest in the craft --physical, emotional, philosophical,

and cultural. I have no doubts that this has aided my discoveries and

insights as well as helped me find direction or solace.

I do not pretend to be a knight or warrior out of history, nor do I imagine

myself their equal. I am a person born and raised within our modern world,

an adherent of a rational scientific world-view as well as admirer of

the Renaissance spirit. Yet, as a student of history, as a committed martial

artist and teacher, I have come to find it curious that without giving

it any attention or effort, the same kind of needs manifested to slowly

direct me toward the same kind of process.

Warrior... Know Thyself

Martial spirit, the sense of being a warrior, exists only by acceptance

of a code that recognizes when and where and what it is right to fight.

This is no mere willingness to fight, nor just ability to fight, but something

more. It requires deep reflective thought. It requires self-assessment.

To discover and commit to reaching such values, I believe history reveals

that it comes into being only through some personal process of meditatio

et contemplatio. Silent, solitary, guided self-reflection.

Martial

spirit, the sense of being a warrior, exists only by acceptance of a code

that recognizes when and where and what it is right to fight. This is

no mere willingness to fight, nor just ability to fight, but something

more.

Self knowledge, to "know thyself", has been a touchstone of

Western philosophy since the Greeks. The self, not the anti-self or non-self,

is sought in relation to the individual's accepted values and beliefs.

To the martial artist this means acknowledging and appraising their own

state of being as a fighting man. Just as Augustine of Hippo wrote, "if

thou shouldst think thou hast reached perfection, all is lost; for it

is the nature of perfection to teach one's imperfections," the 14th

century priest turned master-at-arms Hanko Doebringer taught: "it

is a wise man who fights his own weakness." (This was echoed much

later by Monsieur L'Abbat, in his 1734, Art of Fencing, when he

expressed: "Practice is either good or an evil; all consist in the

choice of it. When you think yourself skillful and dexterous, 'tis then

you are not.")

According to Doebringer, no combatant should fight in anger nor fight

from fear. How else does one consider such matters without contemplatio?

When the early 15th century master Fiore Dei Liberi declares that audacity

is what the art is based upon, how does an individual come to summon and

channel such fortitude without effort in meditatio? Indeed, the

wisdom and prudence Fiore wrote were necessary to a good fighter are qualities

that must be discovered in the self by the self. Paulus Kal's treatise

of 1470 reveals that the fighter should have a clear head and strong heart

in order to perceive his adversary's intentions. How does one learn to

practice this without some means of processing it with that most mysterious

part of our neurological makeup we call the brain?

In the West, the mind and self are not disengaged from contemplation.

Indeed, reason is a virtue, and conscious appreciation of one's own full

identity is something to be sought rather than denied. As the fencing

maestro Vincentio Saviolo wrote in his rapier treatise of 1594, "...the

more skill a man hath of his weapon the more gentle and courteous should

he show himself, for in truth this is rightly the honor of a brave Gentleman,

and so much the more is he to be esteemed: neither must he be a bragger,

or liar, and without truth in his word, because there is nothing more

to be required of a man then to know himself."

Time

spent processing and dealing with what has been accomplished or not accomplished,

considering what has been learned or not learned, is a phenomenon familiar

to high-level athletes and others working in stressful and physically

competitive fields. In such times, the individual may seek to find understanding

and meaning within their present state or degree of progress. When guided,

directed, and focused, this process is essentially what may be called

meditatio. Time

spent processing and dealing with what has been accomplished or not accomplished,

considering what has been learned or not learned, is a phenomenon familiar

to high-level athletes and others working in stressful and physically

competitive fields. In such times, the individual may seek to find understanding

and meaning within their present state or degree of progress. When guided,

directed, and focused, this process is essentially what may be called

meditatio.

I have avoided here discussion of both the metaphysical and theological

as well as not delving into the existential. I have tried instead to emphasize

the emotional or psychological as it is tied to the practitioner's values

and character. In this modern world that is neither chivalric nor honorable,

in our modern society that downplays personal virtue and the more ennobling

aspects of Western heritage in favor of lesser agendas, sincere contemplation

is needed more than ever in my opinion.

We humans are not perfect. And while every martial artist may strive

to perfect their skills and techniques, dealing with each session of practice,

its highs and lows, failures and successes, our frustrations and weaknesses,

requires honest self-inspection and sincere personal evaluation. Every

student of the art at some time asks themselves the same questions of

why they practice, what are they seeking with it, what do they get from

it? To progress and grow as a practitioner these must be addressed by

the individual at some point. This is where in my view the exercise of

contemplatio comes into the craft.

The

mental and emotional control necessary for a warrior is a common theme

throughout military history and is evidenced in writings from the ancient

Greeks to the Renaissance Masters of Defence.

The mental and emotional control necessary for a warrior is a common

theme throughout military history and is evidenced in writings from the

ancient Greeks to the Renaissance Masters of Defence. It would not be

unreasonable to imagine that familiar aspects of Christian prayer and

contemplation may at times have fulfilled a similar role for the Medieval

and Renaissance fighting man. However, no Fechtbuch includes direct

instructions for anything equivalent to the modern practices of meditation

as presented in various manners among popular Asian martial art styles

(of which some is itself an artificial modern invention painted onto contemporary

practice for the interests of wide-eyed Westerners who expect some esoteric

content).

It

would be foolish to imagine that fighting men brought up in a world where

the power and influence of faith surrounded them in every aspect of their

culture and civilization would not seek council and solace through either

inner dialogue or directed prayer as a means of finding peace of mind

or clarity of thought and feelings in order to deal with the mental and

emotional stress that goes hand-in-hand with being a warrior, let alone

finding some philosophical accommodation with their role as fighting men

in a manner that was not self-destructive. Even today, those in similar

positions in the military and paramilitary and other careers involving

conflict resolution can neither suppress nor deny the need for counsel

and clarity. Those who don't, inevitably suffer consequences of self-destructive

behavior, substance abuse, and unhealthy relationship habits, and failure

to deal with their aggressions or find peace of mind. It

would be foolish to imagine that fighting men brought up in a world where

the power and influence of faith surrounded them in every aspect of their

culture and civilization would not seek council and solace through either

inner dialogue or directed prayer as a means of finding peace of mind

or clarity of thought and feelings in order to deal with the mental and

emotional stress that goes hand-in-hand with being a warrior, let alone

finding some philosophical accommodation with their role as fighting men

in a manner that was not self-destructive. Even today, those in similar

positions in the military and paramilitary and other careers involving

conflict resolution can neither suppress nor deny the need for counsel

and clarity. Those who don't, inevitably suffer consequences of self-destructive

behavior, substance abuse, and unhealthy relationship habits, and failure

to deal with their aggressions or find peace of mind.

The need to guide and direct novices in this is yet one more reason why

fraternity, camaraderie, and mentoring are elements of all high level

martial arts study, and we can readily envision this being recognized

to some degree or another within Renaissance fighting guilds and schools

of defense. The frequent appearance in the Fechtbuchs of combatants kneeling

in prayer can itself be seen as not just an acknowledgment of the religiosity

of fighting men at the time, but arguably, of the necessity to address

the non-physical elements of martial arts training. That this aspect notably

declined as European martial arts teachings themselves deteriorated and

simplified down to far more limited and narrowly specialized fencing styles

during the Enlightenment is surely no coincidence.

Contemplatio?

For

what purpose would today's student of Renaissance martial arts engage

in this as part of their routine?

In 1389, Hanko Doebringer expressed that one “should know that

one cannot speak or write about fighting as clearly as one can show and

demonstrate with the hand; therefore use your common sense and reflect

on things further.” (Anglo, Martial Arts, p. 33). In considering

this line as part of the factor of reasoning inherent in Renaissance

martial arts doctrines, it common sense. But an alternate reading of it

equally embraces the idea of contemplatio.

To what purpose would today's student of Renaissance martial arts engage

in this as part of their routine? The answer to me is obvious: to attain

a clear-headed self-awareness, to calm anxiety, to control anger and depression,

to better acknowledge hopes, fears, desires, aspirations, for easing of

physical tension, and to quiet distractions and distracting thoughts that

all impede growth and improvement. The value of introspection lies in

communing with one's self or an external focus to clarify your values,

virtues, and beliefs. The physical performance of martial exercises and

drills is directly related to sharpening mental discipline, improving

insight, increasing creative action, and encouraging intuitive thought

over purely cognitive processing. It is arguably the sole means to reduce

the stress and anxiety associated with impairing athletic performance,

as well as the ability to emotionally endure physical violence. A calm,

relaxed, clear mind as preparation or mental rehearsal before or following

physical routines is well known to improve physical competence.

Continued,

intent, focused thought engages the mind, fuels the imagination, and clarifies

emotion, reason, and desire. A state of quiet, contentless awareness to

reach greater self-awareness, creativity, and a higher level performance

through achieving a relaxed frame of mind is undeniably a beneficial tool

to the serious pursuit of any combative discipline. No martial artist

can ignore this element and expect to fully understand their craft. This

process demands neither ritual nor metaphysical assumption. It simply

requires the individual make the effort of knowing themselves. The lack

of such activity is in my opinion why so few attain satisfaction in their

art. Continued,

intent, focused thought engages the mind, fuels the imagination, and clarifies

emotion, reason, and desire. A state of quiet, contentless awareness to

reach greater self-awareness, creativity, and a higher level performance

through achieving a relaxed frame of mind is undeniably a beneficial tool

to the serious pursuit of any combative discipline. No martial artist

can ignore this element and expect to fully understand their craft. This

process demands neither ritual nor metaphysical assumption. It simply

requires the individual make the effort of knowing themselves. The lack

of such activity is in my opinion why so few attain satisfaction in their

art.

A modern practitioner may like to think it is all just about techniques

and learning movements, but in the long run they discover what the historical

warriors did (and modern ones often do): we don't practice in an ethical/moral

vacuum. We are thinking, feeling beings, and the act of combat, of dealing

or resisting personal violence, of even just training for its possibility,

affects the individual. It alters one's psyche. True arts of fighting,

to one degree or another, deal with this, not just with mere collections

of physical actions and tactical actions.

Every time you practice, you do some form of self-evaluation in which

you ask yourself, "How did I do?" Whether you conclude you did

well or need to improve, you eventually must ask yourself how and by what

means? Whether you feel confident or disappointed, angry or depressed,

invigorated or drained by your performance, some form of subjective consideration

is necessary. What caused you to feel as you do over your practice and

how you deal with it is part of the very process of learning the application

of the craft. We process these things (either consciously or not), and

the best way to do so is to proceed intentionally with sincerity; guiding

yourself through it by making contemplation a rational part of your study.

When

you take moments to meditate and contemplate, what you are then effectively

doing is tying the physical practice you just did -- an in-arguably violent

activity -- to not just your biomechanical performance of it but to your

mental and emotional performance. You are connecting not only to the mere

technical execution of motor skills, but to a larger personal context:

"Who am I that I am doing this?... When and where and why would I

need these skills such that I pursuing them?... How does it affect me?"

In psychological terms, you are linking the physical, the mental, the

emotional, the ethical, and the spiritual, if you prefer, all together.

It is this that allows you to not fight out of fear or anger, or make

pridefulness your motive. It is by this that you relate to fortitudo,

sapientia, prudentia, and audacia through preudhome

(prowess). It is this that defines martial spirit -- kampfgeist

-- as more than just ability, but as the totality of who you are. And

it is this which I believe is reflected in the chivalric values we infer

from the source teachings, even though never presented as doctrine. More

profoundly, it is through this that the martial artist finds greater meaning

and becomes a better fighter. But, if the only meaning to you consists

of "I just like to practice fighting" then you are profoundly

ignorant and have no clue what martial arts are ultimately about, for

they go beyond self-defense. The naïve student who says, "I

just want to learn how to fight," will never achieve a full appreciation

of their craft nor realize their full potential. And they will continue

to struggle against their baser natures. When

you take moments to meditate and contemplate, what you are then effectively

doing is tying the physical practice you just did -- an in-arguably violent

activity -- to not just your biomechanical performance of it but to your

mental and emotional performance. You are connecting not only to the mere

technical execution of motor skills, but to a larger personal context:

"Who am I that I am doing this?... When and where and why would I

need these skills such that I pursuing them?... How does it affect me?"

In psychological terms, you are linking the physical, the mental, the

emotional, the ethical, and the spiritual, if you prefer, all together.

It is this that allows you to not fight out of fear or anger, or make

pridefulness your motive. It is by this that you relate to fortitudo,

sapientia, prudentia, and audacia through preudhome

(prowess). It is this that defines martial spirit -- kampfgeist

-- as more than just ability, but as the totality of who you are. And

it is this which I believe is reflected in the chivalric values we infer

from the source teachings, even though never presented as doctrine. More

profoundly, it is through this that the martial artist finds greater meaning

and becomes a better fighter. But, if the only meaning to you consists

of "I just like to practice fighting" then you are profoundly

ignorant and have no clue what martial arts are ultimately about, for

they go beyond self-defense. The naïve student who says, "I

just want to learn how to fight," will never achieve a full appreciation

of their craft nor realize their full potential. And they will continue

to struggle against their baser natures.

Insight from Reflection - Thinking it Through

When frequent reference is made in our historical source teachings to

the fighter acting with good "spirit" or "heart,"

one must ask oneself what does it mean in the study of this discipline?

How will you consider it yourself? In what way will you address it in

the context of your own practice? By what means will you reach your conclusions?

By what other means do we learn to channel our tendency to violence and

direct aggressive impulses? These things cannot be attained through informal

social contact, nor in committee meetings, group panels or online forums,

and certainly not by email, texting, or casual conversation. These things

must spring from somewhere for the modern student. To the young fighter

or martial arts novice simply wanting to get good, win some bouts, or

feel powerful in his techniques, these are admirable goals, but they are

only one part of the path, the first part of the journey toward whatever

kind of martial artist they are going to eventually be. Because the simple

truth is, the thing that the beginner as well as the intermediate student

does not usually comprehend is that the study of martial discipline is

far more than just techniques and principles, it is attitude, and that

attitude is developed from within. Thus, to look within requires you meditate

and contemplate upon who you are and what you want to be ...and how you

will try to get there. This is not Eastern, this is not Western, this

is not anywhere in between, this is simply human.

Because

the simple truth is, the thing that the beginner as well as the intermediate

student does not usually comprehend is that the study of martial discipline

is far more than just techniques and principles, it is attitude, and that

attitude is developed from within.

More than once the last ten years I have seen a top student of mine eventually

deteriorate in his ability or plateau in his skills such that they came

to frustration and disappointment. The went from rapid rise to rapid collapse

and disillusionment in their craft, and struggled with issues in their

private and professional lives all because they could not find their center,

their core, their values and their moral compass. I watched as they slowly

abandoned the values and dismissed the spirit of Renaissance martial arts

practice and in each of these cases I knew the cause was their own lack

of introspection and inability to find solace within themselves. When

one cannot be true to themselves or their fellows it's impossible be true

to the practice of a craft that demands sincerity of effort and self-honesty

in one's progress. Again, it's not all just about techniques and fighting

moves. I have also witnessed first-hand one close former student

engage for years in cynical self-denying and self-negating behavior as a

way of dealing with personal stress made worse by the philosophical

vacuum of his own total lack of introspection.*

My

advice to every young student is that if you proceed under the illusion

that becoming adept is solely a matter of physical prowess in techniques

and principles, you will never master the Art. I have often spoken at

length on the ethical and spiritual component intrinsic to the source

teachings of Renaissance martial arts (and will soon be publishing on

this), so we come to the question: how do you imagine our forebears strived

for such knowledge and sought personal insight? They didn't do it through

committees and conferences. They meditated upon it. Internalization of

training, of proper attitude, of discipline, of purpose and meaning do

not come about through physical exercise alone, nor even when combined

with intellectualizing of combat methods. Rather, there is another aspect

long recognized: solitary internal reflection. In his great martial treatise

of 1570, the master Joachim Meyer stated that in practicing the art of

combat "the student is very masterfully stimulated to greater reflection

to use every kind of advantage, along with many more other uses that this

practice brings with it." Greater reflection indeed... My

advice to every young student is that if you proceed under the illusion

that becoming adept is solely a matter of physical prowess in techniques

and principles, you will never master the Art. I have often spoken at

length on the ethical and spiritual component intrinsic to the source

teachings of Renaissance martial arts (and will soon be publishing on

this), so we come to the question: how do you imagine our forebears strived

for such knowledge and sought personal insight? They didn't do it through

committees and conferences. They meditated upon it. Internalization of

training, of proper attitude, of discipline, of purpose and meaning do

not come about through physical exercise alone, nor even when combined

with intellectualizing of combat methods. Rather, there is another aspect

long recognized: solitary internal reflection. In his great martial treatise

of 1570, the master Joachim Meyer stated that in practicing the art of

combat "the student is very masterfully stimulated to greater reflection

to use every kind of advantage, along with many more other uses that this

practice brings with it." Greater reflection indeed...

Thus, just as early Christians would meditate upon the meaning of scripture

and contemplate their personal relation to it, so too may a modern student

approach the meaning of Renaissance martial teachings and its value to

their life and character as the sources themselves would seem to imply.

As we are told by the Fechtbuchs... "You must study this diligently."

I leave it to the reader to explore this on their own as they see fit.

"...a despondent heart will always be defeated, regardless of all skill.”

- Fechtmeister Sigmund Ringeck, 1440

“... it is requisite that [swordsmen] carry the principles of this Art,

surely fixed in their minds and memories, by means whereof they may become bold and resolute…”

- Mastro Giacomo Di Grassi, 1570

End note: For me personally, this is the hardest piece

I have ever written. Because it does not deal directly with fighting doctrine

or historical methods, nor arms and armor, but with martial culture --and

in a manner that I cannot directly provide evidence for. Yet, it concerns

a matter which is a part of my own practice. To me, most Westerners' superficial

obsessions with meditation in the pursuit of traditional Asian martial

arts study has always come across as less than sincere. It seemed more

a transcendental longing for something, at least since the Enlightenment,

absent in Western Civilization, mixed with more than a little pretentious

role-playing. So, to eventually find support for a similar yet distinctly

different element within our craft was at first a surprise. But as with

so many aspects of Renaissance martial culture, on closer inspection its

distinctions stand out.

*As of Jan 2013, it is not surprise to now see even the US

Marine Corps is now exploring the need for it's fitting men to acquire

some semblance of self-awareness through focused thought on themselves

and their immediate environment as a means to address both post-combat

stress and to enhance combat readiness and post-combat stress: http://tinyurl.com/USMC-Mindfullness.

The personal and cultural values, and the connection to heritage,

previously present within Marine recruits of earlier generations of

Marine recruits have no doubt been found insufficient in providing the

mental-emotional foundation that permits any fighting man to function at

their best. Go figure.

Bibliography:

Green, Thomas A. Editor, Martial Arts of the World, an Encyclopedia"

Volume One A-Q. ABC-CLIO, Inc. 2001.

|