Prowess is a "Three-Legged Stool"

By

John Clements

ARMA Director

"He who wants to have honor in arms should have

knowledge, fortitude and courage."

- Master Filippo Vadi, c. 1482

After

decades of personal study, I love being able to cultivate interest in

historical arms and armor among younger generations. Encouraging this

among youths has become a major focus of my work. Some of the most interesting

questions I'm asked about historical fencing and weaponry come from youths

who very often will pose the most direct yet challenging inquiries to

answer. For example, they might ask: why are there so many swords, or

why did swords change so much over time, how were swords made, or what

is the better sword? These are basic questions with complex answers. I

enjoy these kinds of questions because they challenge me to not only express

things succinctly, but also to examine just what it is we know about this

subject and how we came to know it. After

decades of personal study, I love being able to cultivate interest in

historical arms and armor among younger generations. Encouraging this

among youths has become a major focus of my work. Some of the most interesting

questions I'm asked about historical fencing and weaponry come from youths

who very often will pose the most direct yet challenging inquiries to

answer. For example, they might ask: why are there so many swords, or

why did swords change so much over time, how were swords made, or what

is the better sword? These are basic questions with complex answers. I

enjoy these kinds of questions because they challenge me to not only express

things succinctly, but also to examine just what it is we know about this

subject and how we came to know it.

Recently, a school-age child inquired with me as to "what was the

most important thing in studying swordsmanship?" My thoughts ran

immediately to the varied statements by Renaissance Masters of Defence

listing the many qualities and attributes necessary for a good fighter,

or their descriptions of the critical characteristics of a good swordsman.*

Their quotes on the topic are insightful and offer us practical advice,

to be sure. But their wisdom is not ideal for a short answer.

In

considering the question the child posed, I was reminded of the scene

in John Boorman's superb film, Excalibur, in which King Arthur

confronts Merlin to answer the question of what trait is the most important

in a knight. Caught off guard, Merlin tries to say that there are several,

so that it's similar to the metals blended to make a good sword blade.

Forced to provide a direct response, though, Merlin ends up replying with

one he views as standing above all. In

considering the question the child posed, I was reminded of the scene

in John Boorman's superb film, Excalibur, in which King Arthur

confronts Merlin to answer the question of what trait is the most important

in a knight. Caught off guard, Merlin tries to say that there are several,

so that it's similar to the metals blended to make a good sword blade.

Forced to provide a direct response, though, Merlin ends up replying with

one he views as standing above all.

In my attempt to avoid too scholarly a reply to the youth's question,

my answer was far less dramatic than Merlin's, but I think I still managed

to encapsulate the teachings of the historical fight-books while giving

context to the modern study of historical swordsmanship -the context being

that it was something needed to protect oneself from serious violence.

Swordsmanship was a central part of Renaissance martial arts teachings.

It represents a larger portion of the thoughts and theories on self-defence

from the period than any other topic. Its study and culture directly addressed

the fundamental ideas and concepts of close combat more so than any other

weapon or martial teachings from the time. In any martial discipline there

are undeniably several equally important elements combined, but, if anything,

their synergy is even more important in the science and art of fencing.

My view is that the thoughts of the Renaissance Masters of Defence can

be summarized as recognizing that the craft involves three key components.

Think of them as each being one leg of a sturdy "three legged stool."

Take away any one leg and the stool collapses. With all three legs in

proportion the stool supports the weight placed upon it.

The

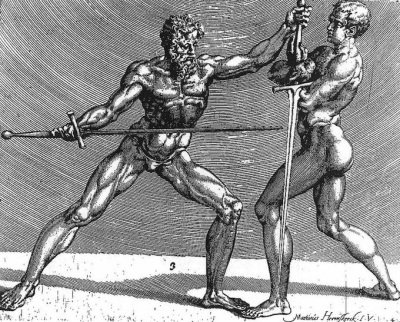

first "leg" of this stool is the Art itself: the idea

of having an actual fighting method. You need to have some proven

systematic combat teachings based upon sound principles of self-defence.

Repeated examples can be found in Renaissance martial arts literature

of masters cautioning against ignorance that there somehow isn't

an actual "art" of fighting. They warn of those skeptical of

its value over the natural advantage of physique alone or just the practical

know-how that comes from experience. That is to say, fighting is a subject

that can be studied, understood, and improved upon just as any other discipline. The

first "leg" of this stool is the Art itself: the idea

of having an actual fighting method. You need to have some proven

systematic combat teachings based upon sound principles of self-defence.

Repeated examples can be found in Renaissance martial arts literature

of masters cautioning against ignorance that there somehow isn't

an actual "art" of fighting. They warn of those skeptical of

its value over the natural advantage of physique alone or just the practical

know-how that comes from experience. That is to say, fighting is a subject

that can be studied, understood, and improved upon just as any other discipline.

Yet, the whole point of the Art is to overcome naturally stronger opponents

-or at least to give you a chance against those who have inherent physical

advantages. The mid-15th century fight-book teachings of the Codex

Wallerstein tell us specifically that in serious combat a weak fighter

can be equal to a strong opponent "…if he has previously learned."

That is, if he has skill. Essentially, this means having a codified

doctrine that essentially instructs in the applied knowledge of timing,

distance, leverage, and technique -a science of defence, as it

was known. Despite differences between fighters and methods, as the Master

Joachim Meyer expressed in 1570, everything still relies upon a common

knowable foundation. But just having a fighting method is not enough.

One must acquire proficiency in its earnest application.

This

brings us to the second "leg" of the stool -conditioning.

That is, you must be exercised in the physical performance of a

fighting method and accomplished in its motions. This means you need to

have the requisite physicality to develop the ability to move with essential

coordination and act with necessary force. Being aware of theories and

teachings doesn't do you any good if you can't effectively use them for

lack of training. One must actually practice. Techniques are ineffective

if you lack the speed and power that only comes through experience moving

with control. This

brings us to the second "leg" of the stool -conditioning.

That is, you must be exercised in the physical performance of a

fighting method and accomplished in its motions. This means you need to

have the requisite physicality to develop the ability to move with essential

coordination and act with necessary force. Being aware of theories and

teachings doesn't do you any good if you can't effectively use them for

lack of training. One must actually practice. Techniques are ineffective

if you lack the speed and power that only comes through experience moving

with control.

Master Liechtenauer is chronicled in 1389 as teaching that "exercises

are better than art, as exercises help without the art, but the art is

of no help without exercises." This is true. Merely studying so that

you "know all about it" without being competent in adversarially

employing it is useless for achieving real skill. This comes only through

devoted physical effort. The Art isn't more important than conditioning.

Why? Because, generally, someone of physical dominance with a little bit

of training yet a good martial attitude is going to overcome someone of

more training but lesser physique and weaker mindset. And yet, master

Liechtenauer also rightly tells us that the whole purpose of the Art is

to overcome an opponent who is stronger than you. He even asks that if

this were not so what then would be the purpose of the Art? As the master

Filippo Vadi expressed it in 1482, "cunning defeats any strength."

In other words, skillfulness and training overcome natural brutality.

Just possessing theoretical knowledge is not enough, though. You still

have to have to have capacity in applying it, and the degree required

for this can vary between disciplines or methods. Even then, athleticism

and endurance only carry you so far in fighting. It doesn't matter if

you are tough and fit if you lack any real craft of fighting to best harness

it.

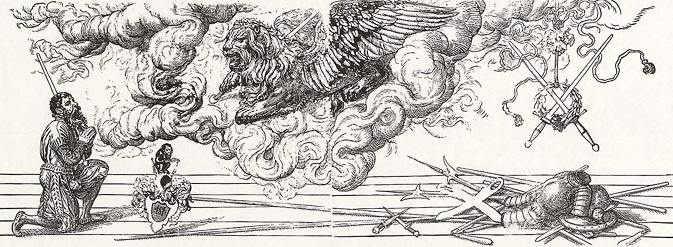

Similarly,

along with practical know-how and ability, one must also have the right

mindset or will. This then is the third leg of the stool: attitude.

Just as one hones technical skill and physical ability, one must develop

a certain Kampfgeist ("martial spirit"). The psychological

component -the mental/emotional (even spiritual and ethical) outlook-

is no less critical. Similarly,

along with practical know-how and ability, one must also have the right

mindset or will. This then is the third leg of the stool: attitude.

Just as one hones technical skill and physical ability, one must develop

a certain Kampfgeist ("martial spirit"). The psychological

component -the mental/emotional (even spiritual and ethical) outlook-

is no less critical.

History is filled with examples attesting to the importance of mindset

and fighting morale for the warrior. The ideal mental state is to neither

fight in fear nor out of anger. It's easy to imagine a determined combatant

declaring, "Nothing's gonna stop me!" or "I'll crush you"

or even exclaiming in panic, "I don't know what to do!?" Dealing

with such emotions is part of what a fighting discipline is all about.

You must keep your head in the game, stay focused, not be distracted and

"out of it" or otherwise distraught in some debilitating way.

Otherwise, all your training and conditioning will fail no matter the

sophistication of your skill set. To act resolutely and boldly when faced

with violence and be free of doubt and anxiety as you do, is really (in

the chivalric sense) to display valor.

Still,

one cannot rely only on being determined and courageous. Acting indomitably

in the face of adversity and violent conflict is certainly valuable, but

on its own it simply can't compensate for lack of wisdom and deficiency

of ability. It won't get you very far when you're not sufficiently trained

in a sound martial discipline -the other two legs. All of this is still

tied together with a proper fighting mindset or, as Master Fiore dei Liberi

expressed it in 1410, audacity… such is what the Art is all about.

Fiore stressed that the mind should be free from fear, and only in this

condition can you develop your capacities and improve yourself. This is

a proven and trustworthy sentiment in the study of "combatives."

The historical writings spend a great deal of time addressing this psychological

component.* Still,

one cannot rely only on being determined and courageous. Acting indomitably

in the face of adversity and violent conflict is certainly valuable, but

on its own it simply can't compensate for lack of wisdom and deficiency

of ability. It won't get you very far when you're not sufficiently trained

in a sound martial discipline -the other two legs. All of this is still

tied together with a proper fighting mindset or, as Master Fiore dei Liberi

expressed it in 1410, audacity… such is what the Art is all about.

Fiore stressed that the mind should be free from fear, and only in this

condition can you develop your capacities and improve yourself. This is

a proven and trustworthy sentiment in the study of "combatives."

The historical writings spend a great deal of time addressing this psychological

component.*

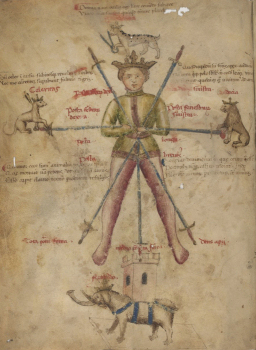

Most all the major Renaissance masters and fight-book sources list physical

elements combined with mental ones when they describe the things that

the Art itself consists of or that a practitioner requires in order to

master it. At the risk of reformulating their ideas, these lists can all

be condensed down to essentially three factors: the tactical, the physical,

and the mental. These three factors are not unlike how, in order to conduct

war, a nation state must have three critical things: strategic doctrine,

military capacity, and political will. Absent any one and they will likely

suffer  defeat

when they enter into armed conflict. One way to look at this is that even

as there are natural physical and mental dispositions at work, it is training

that provides competence to nurture our confidence as fighters. Or as

Master George Silver put it in 1599, because people "desire to find

a true defence for themselves in their fight, therefore they seek it diligently,

nature having taught us to defend ourselves and Art teaching us how." defeat

when they enter into armed conflict. One way to look at this is that even

as there are natural physical and mental dispositions at work, it is training

that provides competence to nurture our confidence as fighters. Or as

Master George Silver put it in 1599, because people "desire to find

a true defence for themselves in their fight, therefore they seek it diligently,

nature having taught us to defend ourselves and Art teaching us how."

In answering the child's question about swordsmanship's single most important

thing, my reply was that there isn't one. There are three. I don't see

how we could say any one takes precedent over the other two. They each

require one another. They are a trinity, inseparable and interconnected,

synergistic and interdependent. The best word I have come across to use

for describing what these three "legs" represent is preudhome

or knightly prowess: know-how and skill matched to a focused will. It's

all about applying the central underlying principia of self-defense,

but it recognizes that acquiring a knowledge base of fighting actions

is ultimately both a mental and physical process. Preudhome incorporates

all three aspects. Martial ability is knowledge of the core tenets and

principles, while conditioning is the physicality of exercise and training

in techniques, and attitude is the psychologic (i.e.,the mental

outlook and emotional state). All of this -knowledge, conditioning,

attitude- constitutes skill in personal close-combat. It really is

akin to the three legs of a stool; if missing any one it will collapse.

This gives even greater weight to the cautionary words of Master Filippo

Vadi from his treatise on fighting in c.1482: "He who wants to have

honor in arms should have knowledge, fortitude and courage, if these he

lacks, he'd better renounce [study]" In other words, mastering your

martial art means having all three legs: knowledge, conditioning,

and attitude -the very "stool of defence."

**Despite decades of pop-culture commercialism and hyperbole

to the contrary, learning martial arts is actually pretty easy. Ultimately,

it comes down to acquiring basic core tenets that teach fundamental principles

universal to all personal self-defense. It's really a matter of having

in place a working doctrine of proven concepts matched to a sufficient

repertoire of learned techniques -what we might term, practicum et

principia. In a sense, when learning a martial art every student will

have certain questions about what techniques and concepts they are shown.

For example: "What was that?" "How do I do that?"

"When should I use that?" "How do I practice that?"

"Am I doing that correctly?" These are fundamental issues

that occur continually. But the ultimate question for a martial artist

may be, "What happens if I have to use that for real?"

In other words, what results physically and psychologically to the fighter

from using their violent skills in earnest emergency? The Renaissance

Masters of Defence were far from silent in addressing the topic.

|