|

The

Two-Handed Great Sword The

Two-Handed Great Sword

Making lite of the issue of weight

By Anthony

Shore

For many

years in the historical-reenactment/renaissance faire communities,

I have listened to lectures regarding the weight of the two-handed

great sword. I have heard endless stories of how this magnificent

weapon often weighed in excess of 20 pounds with such justifications

as they "needed to be heavy to smash through plate armor or to

unhorse knights on the battlefield." Other arguments include

such claims as how Medieval Europeans somehow did not possess the

technology to produce lightweight, quality steel weapons. This kind

of statement usually includes some reference to Japanese swords and

"technologically superior" folded steel.

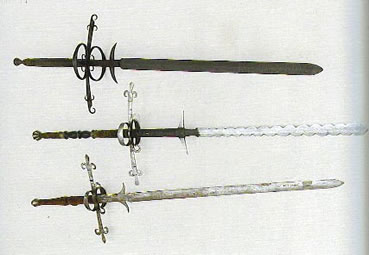

The respected work, Swords and Hilt Weapons, offers this description

of the weapon:

"The two-handed sword was a specialized and effective infantry

weapon, and was recognized as such in the fifteenth and sixteenth

centuries. Although large, measuring 60-70 in/150-175 cm overall,

it was not as hefty as it looked, weighing something of the order

of 5-8 lbs/2.3-3.6 kg. In the hands of the Swiss and German infantrymen

it was lethal, and its use was considered as special skill, often

meriting extra pay. Fifteenth-century examples usually have an expanded

cruciform hilt, sometimes with side rings on one or both sides of

the quillon block. This was the form which remained dominant in

Italy during the sixteenth century, but in Germany a more flamboyant

form developed. Two-handed swords typically have a generous ricasso

to allow the blade to be safely gripped below the quillons and thus

wielded more effectively at close quarters. Triangular or pointed

projections, known as flukes, were added at the base of the ricasso

to defend the hand." (p. 48)

The

purpose of this article is to dispel some of the myths and misinformation

that have been circulating around the Renaissance Faire and the Highland

Games communities as well as among sword enthusiasts in general regarding

the two-handed great sword. While I am certainly no expert in the

field myself, I do know how to ask questions and whom to ask. Over

a period of some eight weeks I corresponded on the subject of the

two-handed great sword with arms curators and authorities at various

museums and armories throughout Europe. This article is a compilation

of data based on some of the responses I have received as well as

information from other sources on the subject. The

purpose of this article is to dispel some of the myths and misinformation

that have been circulating around the Renaissance Faire and the Highland

Games communities as well as among sword enthusiasts in general regarding

the two-handed great sword. While I am certainly no expert in the

field myself, I do know how to ask questions and whom to ask. Over

a period of some eight weeks I corresponded on the subject of the

two-handed great sword with arms curators and authorities at various

museums and armories throughout Europe. This article is a compilation

of data based on some of the responses I have received as well as

information from other sources on the subject.

Factual Evidence as to Weight

Robert C. Woosnam-Savage of the Royal Armouries at Leeds writes:

"The fighting two-handed sword, weighed (on average) between

5-7 lbs. I give the following three examples, randomly chosen from

our own collections, which I hope are adequate to make the point:

Two-handed sword, German, c.1550 (IX.926) Weight: 7 lb 6oz.

Two-handed sword, German, dated 1529 (IX.991) Weight: 5 lb 1oz.

Two-handed sword, Scottish, mid 16th century, (IX.926) Weight: 5

lb 10oz.

(I know another of this last type, in a Glasgow Museum, that weighs

in at 5 lbs exactly!)."

Robert C Woosnam-Savage

Curator of European Edged Weapons

In an e-mail correspondence with Mr. David Edge of the Wallace Collection

in London, Mr. Edge states:

"Original weapons are indeed far lighter than most people

realize… 3lbs for an 'average' late-medieval cross-hilt sword,

say, and 7-8 lbs for a Landsknecht two-handed sword, to give just

a couple of examples from weapons in this collection. Processional

two-handed swords are usually heavier, true, but rarely more than

10 lbs. The heaviest and most enormous sword in our entire Armoury

only weighs 14 lbs and was probably ceremonial."

David Edge

Acting Head of Conservation, and Armoury Curator/Conservator

Henrik Andersson, an archives librarian at the Royal Armoury of Stockholm,

offered a detailed categorized list of some of their collection. Below

are some of the examples in the armouries collection of two-handed

weapons, their weights and dimensions and approximately when they

were made or commonly used. Mr. Andersson supplied this list in metric

which I have translated into U.S. Standard. Unlike the ceremonial

pieces, none of the fighting weapons exceeded 4 pounds and the heaviest

ceremonial was less than 11.

Two-handed sword

(Germany) Fifteenth C.

Length: 1375 mm (54.21 inches)

Blade: 920 mm (36.2 inches)

Weight: 1600 gr (3.5 lbs) |

Ceremonial Two-handed sword

(Germany) c. 1600

Length: 1275 mm (50.19 inches)

Blade: 1000 mm (39.37 inches)

Weight: 2330 gr (5.1 lbs) |

Two-handed sword

(Germany) 1475-1525

Length: 1382 mm (54.40 inches)

Blade: 1055 mm (41.53 inches)

Weight: 1550 gr (3.41 lbs) |

Ceremonial Two-handed sword

(Germany) end of Sixteenth C.

Length: 1422 mm (55.98 inches)

Blade 1029 mm (40.51 inches)

Weight: 2700 gr (5.95 lbs) |

Two-handed sword

(Germany ) end of Fifteenth C.

Length: 1473 mm (58 inches)

Blade: 1066 mm (41.97 inches)

Weight: 2720 gr (5.99 lbs) |

Ceremonial Two-handed sword

(Munich) 1575

Length: 1643 mm (64.69 inches)

Blade: 964 mm (37.95 inches)

Weight: 3500 gr (7.72 lbs) |

Two-handed sword

(Germany) c. 1500

Length: 1340 mm (52.75 inches)

Blade: 955 mm (37.6 inches)

Weight: 1390 gr (3.06 lbs) |

Ceremonial Two-handed sword

(Germany) end of Sixteenth C.

Length: 1817 mm (71.53 inches)

Blade: 1240 mm (48.81 inches)

Weight: 3970 gr (8.75 lbs) |

One-and-a-half-handed sword

(Germany) c. 1475-1525

Length: 1153 mm (45.39 inches)

Blade: 932 mm (36.69 inches)

Weight: 1320 gr (2.91 lbs) |

Ceremonial Two-handed sword

(Germany) end of Sixteenth C.

Length: 1893 mm (74.52 inches)

Blade: 1313 mm (51.69 inches)

Weight: 4830 gr (10.64 lbs) |

A question of technology

In

movies and other popular media we often are given the impression that

European sword smiths were large, brutish folk who were not the brightest

of people and capable only of pounding out rough hewn, iron blades.

(This kind of statement usually includes some reference to the masterful

Japanese working with folded steel--disregarding that the Japanese

never developed the spring steel technology which made European swords

so resilient and flexible). The mistake here may be that we confuse

swordsmithing with blacksmithing…which is similar, but not quite

the same thing. Swordsmiths of the day were often very intelligent,

learned craftsmen who gave a great deal of time to the study of metals

and, the forging of a good sword was often the cumulative effort of

a group of highly skilled and artistic men, each with his own specific

task in the creation of a weapon. There were often entire villages

or towns such as Passau or Solingen, Germany, or Toledo in Spain which

were dedicated to the construction and forging of arms and armour. In

movies and other popular media we often are given the impression that

European sword smiths were large, brutish folk who were not the brightest

of people and capable only of pounding out rough hewn, iron blades.

(This kind of statement usually includes some reference to the masterful

Japanese working with folded steel--disregarding that the Japanese

never developed the spring steel technology which made European swords

so resilient and flexible). The mistake here may be that we confuse

swordsmithing with blacksmithing…which is similar, but not quite

the same thing. Swordsmiths of the day were often very intelligent,

learned craftsmen who gave a great deal of time to the study of metals

and, the forging of a good sword was often the cumulative effort of

a group of highly skilled and artistic men, each with his own specific

task in the creation of a weapon. There were often entire villages

or towns such as Passau or Solingen, Germany, or Toledo in Spain which

were dedicated to the construction and forging of arms and armour.

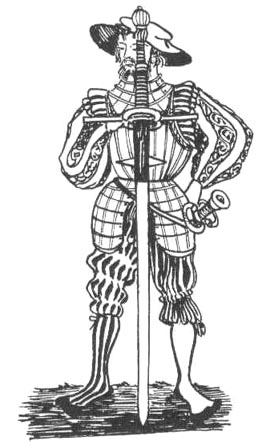

How was this weapon used?

Part

of the "myth" surrounding this weapon may be from a lack

of understanding of how it was used. As weapons, swords are designed

to fill specific needs. In a fight, one gains an advantage in several

ways, two of which are: keeping your opponent from getting close enough

to strike and, being able to strike your opponent before he can strike

you. This requires two things; 1: A weapon capable of striking from

a distance and, 2: A weapon light enough to be wielded quickly. One

of the advantages of this weapon was length, which meant it had greater

ability to reach an opponent from a distance while preventing him

from reaching you. An inordinately heavy blade could not accomplish

these goals. Part

of the "myth" surrounding this weapon may be from a lack

of understanding of how it was used. As weapons, swords are designed

to fill specific needs. In a fight, one gains an advantage in several

ways, two of which are: keeping your opponent from getting close enough

to strike and, being able to strike your opponent before he can strike

you. This requires two things; 1: A weapon capable of striking from

a distance and, 2: A weapon light enough to be wielded quickly. One

of the advantages of this weapon was length, which meant it had greater

ability to reach an opponent from a distance while preventing him

from reaching you. An inordinately heavy blade could not accomplish

these goals.

The two-handed sword was also versatile in the variety of ways it

could be used, the blade for cutting and thrusting, the hilt for smashing

(or more appropriately, pummeling) and, the cross (quillons) for hooking

either your opponent or his weapon. With this in mind, I am left thinking

that this weapon required more skill than muscle to wield. Why is

it then that we so often hear and see such fantastic stories of massively

heavy weapons wielded by Herculean warriors? Because this is what

the media gives us and for some, it's probably just easier to believe

what they see in the movies and accept it as fact. But also, this

is what we expect of our heroes. A super human hero requires an equally

powerful weapon. Reality and myth often clash and the truth gets lost

in the story. (See: Fence

With All Your Strength).

Vivian Etting, Curator of the National Museum of Denmark, in a recent

correspondence offered the following:

"In the Medieval and Renaissance collections at the National

Museum of Denmark we have several very fine two-handed swords. This

type of sword was used primarily in middle and northern Europe from

about 1400 up to the beginning of the 16th Century. It was a combined

cut-and-thrust weapon, which often was manufactured in Passau or

Solingen in Germany. Originally it was a sword, used by armed knights

on horseback, but in the end of the 15th century it was used by

the infantry as well. Thus the big cavalry sword developed into

the two-handed sword, which in turn became the weapon of the Landsknecht."

John Clements offers this summation of the weapon:

"In contrast to longswords, technically, true

two-handed swords (epee's a deux main) or "two-handers"

were actually Renaissance, not Medieval weapons. They are really

those specialized forms of the later 1500-1600's, such as the Swiss/German

Dopplehänder ("double-hander") or Bidenhänder

("both-hander"). The popular names Zweihander /

Zweyhander are actually relatively modern not historical

terms. English ones were sometimes referred to as "slaughters-words"

after the German, Schlachterschwerter ("battle swords").

While used similarly to longswords, and even employed in some duels,

they were not identical in handling or performance. No historical

sources for fencing with these specific weapons have survived. These

weapons were used primarily for fighting among pike-squares where

they would hack paths through lobbing the tips off opposing halberds

and pikes then slashing and stabbing among the ranks. Wielded by

the largest and most impressive soldiers (Doppelsoldners,

who received double pay), they were also used to guard banners and

castle walls.

Many

of these weapons have compound-hilts with side-rings and enlarged

cross-guards of up to 12 inches. Most have small, pointed lugs or

flanges protruding from their blades 4-8 inches below their guard.

These parrierhaken or "parrying hooks" act almost as a

secondary guard for the ricasso to catch and bind other weapons

or prevent them from sliding down into the hands. They make up for

the weapon's slowness on the defence and can allow another blade

to be momentarily trapped or bound up. They can also be used to

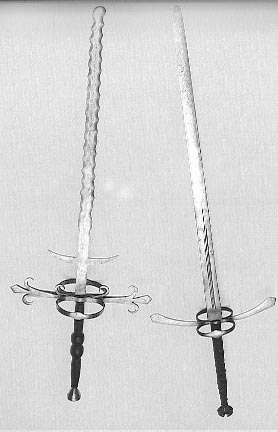

strike with. Certain wave or flame-bladed two-handed swords have

come to be known by collectors as flamberges, although this they

are more appropriately known as flammards or flambards (the German,

Flammenschwert). The wave-blade form is visually striking

but really no more effective in its cutting than a straight one.

There were also huge two-handed blades known as "bearing-swords"

or "parade-swords" (Paratschwert), weighing up

to 12 or even 15 pounds and which were intended only for carrying

in ceremonial processions and parades." Many

of these weapons have compound-hilts with side-rings and enlarged

cross-guards of up to 12 inches. Most have small, pointed lugs or

flanges protruding from their blades 4-8 inches below their guard.

These parrierhaken or "parrying hooks" act almost as a

secondary guard for the ricasso to catch and bind other weapons

or prevent them from sliding down into the hands. They make up for

the weapon's slowness on the defence and can allow another blade

to be momentarily trapped or bound up. They can also be used to

strike with. Certain wave or flame-bladed two-handed swords have

come to be known by collectors as flamberges, although this they

are more appropriately known as flammards or flambards (the German,

Flammenschwert). The wave-blade form is visually striking

but really no more effective in its cutting than a straight one.

There were also huge two-handed blades known as "bearing-swords"

or "parade-swords" (Paratschwert), weighing up

to 12 or even 15 pounds and which were intended only for carrying

in ceremonial processions and parades."

What

about that Plate Armour? What

about that Plate Armour?

Again, it is from a lack of understanding not only of this weapon

but of plate armour that we hear arguments as to how this sword "had

to be large and heavy" in order to smash or cut through it. Warriors

realized that trying to cut through plate with a sword was folly.

More often than not, significant damage would be done to any sword

when trying to "cleave" through plate armor, but you could

get in between the joints with the point of a weapon. Being able to

"punch" through plate was more effective than trying to

hack or bash through it, but if one was determined to actually cut

into a knight outfitted in plate armour, there were much better tools

such as a warhammer or an axe, which had a wide enough blade and could

handle the shock of striking a surface that hard without sustaining

a great deal of damage.

Conclusion

We

can see by the evidence offered from the academic professionals and

other sources presented in this essay, that the two-handed great sword

of Europe was not the crude, lumbering, bludgeon with a point that

it has been made out to be. Although it is considerably heavier than

its smaller relatives, it is still in fact, an agile, lightweight

weapon and if used properly, an incredibly deadly tool for both close-quarter

combat and all-out battlefield melees. We

can see by the evidence offered from the academic professionals and

other sources presented in this essay, that the two-handed great sword

of Europe was not the crude, lumbering, bludgeon with a point that

it has been made out to be. Although it is considerably heavier than

its smaller relatives, it is still in fact, an agile, lightweight

weapon and if used properly, an incredibly deadly tool for both close-quarter

combat and all-out battlefield melees.

This weapon was intended for fighting among the close-pike formations

of the new style of warfare emerging among late 15th and early 16th

century battlefields. It could chop at the shafts of opposing weapons

and when needed be used almost like a pole-arm itself. It was also

an effective tool for dealing with fully armoured mounted knights.

The technology for forging steel has been around for centuries and

a knowledgeable armourer could forge a lightweight, flexible, quality

steel blade that did its job extremely well in the hands of a skilled

warrior.

See

Also:

What did Historical

Swords Weigh?

Academic and Professional Acknowledgements:

Robert C. Woosnam-Savage, is a co-author of "Brassey's

Book of Body Armour" and, was Curator of European Arms and Armour

at the Glasgow Museums from 1983-1997 before joining the Royal Armories

at Leeds as curator of European-Edged Weapons. http://www.armouries.org.uk

David Edge, Author of "Arms and Armour of the

Medieval Knight," has given to the world a worthy gift that encapsulates

something of the knowledge he's built in nearly two decades of study

working with the Wallace Collection in London, England. http://www.wallacecollection.org

Henrik Andersson, Royal Armouries of Stockholm, http://www.lsh.se/livrustkammaren/Thehela.htm

Vivian Etting, Curator at the National Museum of Denmark

http://www.natmus.dk/sw1413.asp

John Clements, the Association for Renaissance Martial

Arts. http://www.thearma.org

Special thanks to Michael Campbell of the Alameda

Newspaper Group for his invaluable editing assistance and guidance.

On Line Articles and Resources:

"The Serpent in the Sword, Pattern-welding in

Early Medieval Swords" by Lee A. Jones

http://www.vikingsword.com/serpent.html

"Origins of the Two-Handed Sword" by Neil

H.T. Melville, published in the Journal of Western Martial Art January

2000. http://www.ejmas.com/jwma/articles/2000/jwmaart_melville_0100.htm

"Polished Steel, The Art of the Japanese Sword."

A Lecture given at London University, December 6, 1996 By Kenji Mishina.

http://www.galatia.com/~fer/sword/mishina/lecture.html

"What did Historical Swords Weigh?" by John

Clements, Director of the Association for Renaissance Martial Arts.

http://www.thearma.org/essays/weights.htm

"The Key Role of Impurities in Ancient Damascus

Steel Blades"

http://www.tms.org/pubs/journals/JOM/9809/Verhoeven-9809.html

Higgins Armory Museum

http://www.higgins.org/Research/resources.shtml

Suggested reading:

Blankwaffen. Geschichte und Typenentwicklung im

Europäischen Kulturbereich. By Dr. Heribert Seitz.

Wallace Collection Catalogue. 1962 two-volume

set, by James Mann, plus the 1986 Supplement by A.V.B. Norman. (Contains

weights of every edged weapon in the collection as well as weights

of body armour).

Records of the Medieval Sword. The Boydell

Press 1991 and "The sword in the Age of Chivalry" 1964,

By Ewart Oakeshott.

Swords and Hilt Weapons. M. Coe, et al. Barnes

and Noble Books of New York, 1993.

About the author:

Anthony

Shore is by trade an IT professional but has been fascinated by Medieval

weapons since early childhood. Anthony has been involved for over

10 years in the Historical Reenactment community and has been associated

with a number of guilds focusing on Scottish history and culture between

the

14th and 16th centuries."

|