An Interview with Swordsmith Peter Johnsson An Interview with Swordsmith Peter Johnsson

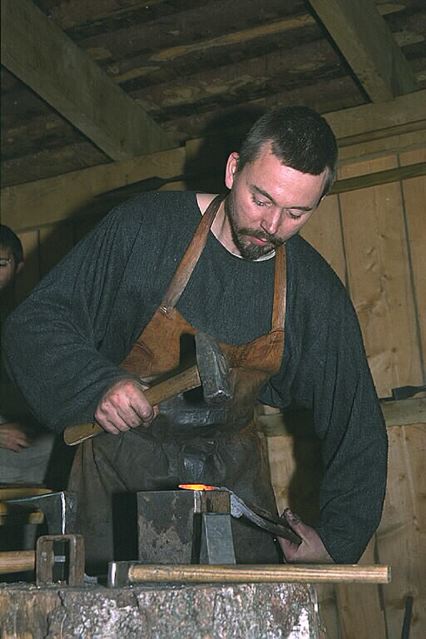

ARMA is proud to bring to the historical fencing community the wisdom, curiosity, and insight of another of the most sincere and humble swordsmiths now working. A researcher and true craftsman as well as historical reenactor, his original work, unique knowledge, and dedicated research are helping raise the craft to new standards of accuracy. Based in Sweden, Peter travels frequently to work research on historical swords and work on reproductions. His views parallel and underscore much of what the ARMA has been expressing for years about real and replica sword.

1. How long have you been making swords, for fun or professionally?

“Professionally, I have been a full time swordsmith since 1999, so this is a rather recent turn of my career. This was after I completed a four-year artistic blacksmith education. I have been fascinated with and studied swords since very early years, though. My first attempts with full-scale steel swords were made some 18 years ago.”

2. Where did you first acquire an interest in historical swordmaking and when did you make the realization you had a real aptitude for doing it?

“My father is a sculptor and had his workshop in the house where I grew up. I spent a lot of my time there as my father worked on his projects in wood, metal and acrylic glass. Swords have always held my fascination. My mother and father told me the old Norse sagas and classic myths and these became part of childhood mythology. Those themes has fueled my imagination ever since.

At the age of eight my father gave me a small anvil as birthday present. On this I made miniature swords until the anvil wore out. I started experimenting with full size steel swords around the age of twenty. Early on I sought out originals in museums to document and learn from. Thanks to very generous and understanding museum curators I got opportunities to handle originals and take notes. The powerful presence that emanates from historical swords was what fascinated me. I wanted to make things that had that feel of reality. At the age of eight my father gave me a small anvil as birthday present. On this I made miniature swords until the anvil wore out. I started experimenting with full size steel swords around the age of twenty. Early on I sought out originals in museums to document and learn from. Thanks to very generous and understanding museum curators I got opportunities to handle originals and take notes. The powerful presence that emanates from historical swords was what fascinated me. I wanted to make things that had that feel of reality.

I started out working as an illustrator and graphical designer. I got an MA after four years of studies and worked professionally six year with children’s books and pedagogical material.

Eventually the urge to work with steel and iron became too intense to suppress. Four-year’s education in artistic blacksmithing seemed like a good way to learn new skills. The plan was not to become a swordsmith, but that was the result after making the final project: the reconstruction of the sword of Svante Nilsson Sture.

To me the making of this sword was a point of no return. I still had to accept the fact that I would be a swordsmith fulltime, but it was an inevitable consequence. Now four years later I find myself spending most hours awake studying, designing or making swords.”

3. Do you have an area or period or style you specialize in? 3. Do you have an area or period or style you specialize in?

“Up till now I have mostly worked with the Medieval European sword. I have made some work with Renaissance styles and developed hilts. Lately I’ve started to document and study the early history of the sword. I will most probably venture into Bronze Age, early Iron Age, Roman, migration and early Viking eras in the future. As I am making blades by forging I might as well use the full potential of that and develop my pattern-welding skills.”

4. Do you have a particular favorite piece you most enjoy constructing or working on?

“I tend to stray into periods that are less well known to me. The process of learning about sword design during a specific period is exiting. It also reflects on previous knowledge of already familiar styles. Mostly anything from early Bonze Age to mid-Renaissance is deeply fascinating.

If I had to pick one from the multitude of sword types, it would be the classic Medieval long-sword. Especially those with hollow ground blades.”

5. Can you identify any major breakthrough that transformed your own study of smithing?

“That would be the reconstruction of the sword of Svante Nillson Sture. During this project it became very obvious to me how much a careful study of an original can add to the understanding of both the object and the craft. The image of the sword is clear in the subconscious of everyone. We might think we know what a sword is and looks like, but it is not until we go beyond what is obvious the real fun starts. Making a sword is a balance act. Opposing qualities needs to be set off against each other. It is fascinating to see how ancient craftsmen found brilliant solutions to these problems.”

6. What was one of the hardest skills to learn in bladesmithing? 6. What was one of the hardest skills to learn in bladesmithing?

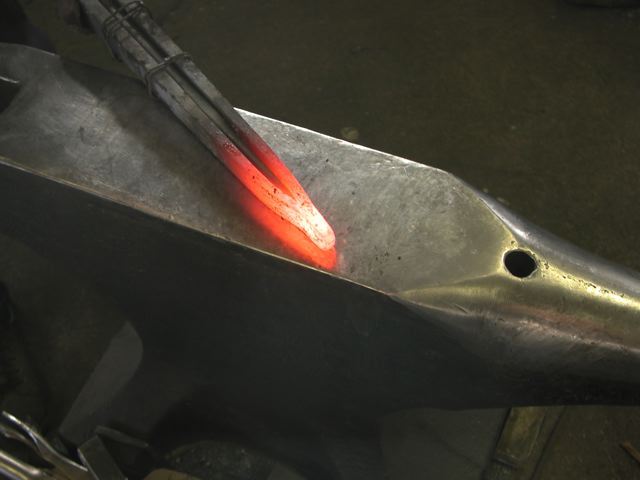

“It is not so much learning the various aspects of the craft as much as learning to be happy with what you presently can do, while ever striving to become a better craftsman. Working the steel with the hammer or welding steel at high temperatures is a matter of timing and intimate knowledge of your material and tools. You need to work without too much hesitation. Going back and fixing is not so good. The best is if every blow with the hammer is one step closer to finish. You need to work with a certain speed and flow and the final result is best when it reflects this driving urge and energy. This ‘flow’ or awareness is also critical when heat-treating the blade: You cannot force the steel to harden; you need to be there and know the right moment to act.

Grinding, filing and polishing poses another kind of challenge: here you need to work slowly with a dedication to the final shape. It is a very different mindset than what you have while forging. It takes another kind of temperament to do it well. Just mastering the techniques of the craft will not allow you to make a sword of high quality, however. You need to understand what a sword is beyond the obvious: resilience and sharpness. It does not help if you are skilled with hammer and grinder if you lack an understanding of proportions and dimensions. You need to study what implications shape, mass, heft and edge geometry has on the final function of the weapon. The more detailed your inner vision of the sword is the better is your chance of your work resulting in a good quality piece. I believe the example of historical swords is our best teacher in these matters.”

7. What major tools do you use in your craft? 7. What major tools do you use in your craft?

“Power hammer, hammer and anvil, and belt grinder might seem like the obvious choices, but perhaps files and emery paper are the tools most frequently used.”

8. Is there a piece of work you are most proud of?

“Again, if I had to choose one sword it would be the Svante Nillson Sture. It is a special sword and it was a very special experience making it. …I know I am repeating myself. Recently I have also completed a reconstruction/copy of a beautiful [Oakeshott] type XVIIb in the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum. It took me five years from start to finish, going over various aspects of the original sword and its making. I had to acquire new skills to be able to do it. Because of that, it also holds a special value to me.”

9. Is there a major accomplishment in sword making hope to achieve? 9. Is there a major accomplishment in sword making hope to achieve?

“Making one really good sword from each important era? I guess that is a goal to keep one busy for some years to come? To me, the work of the ancient masters is awe-inspiring. I will ever strive for my work to emulate the same presence and effortless elegance that is often seen in the best of historical swords. This is the result of experience, skill and a deep understanding of the object/subject.”

10. How active are you now or have you been in training or practicing in with different swords?

“Not very active, I’m afraid. I have been attending some seminars on historical fencing, but I will never aspire to learn the sword as a proficient swordsman. I just hope to get a general idea of the practical use of the sword by taking part in workshops on various styles. Different fencing techniques demand various specific design solutions. Different swords are best suited for different techniques. A grosses messer can exploit strengths that a double-edged single hand sword does not have to the same degree. Size, mass, blade type and style of hilt will all have profound and subtle effects on how the weapon is best put to use. These facts are helpful when analyzing originals or designing new swords.”

11. How would you say today’s sword industry compares to that of say 10 or 15 years ago? 11. How would you say today’s sword industry compares to that of say 10 or 15 years ago?

“It seems like there is a higher awareness of the importance of historical accuracy and the need to base designs on, or at least relate them to historical examples. This might be just marketing lingo in many cases, but I think there is also a reaction to a real demand from customers as well.

It is exiting to see if the growing interest in historical swordsmanship might lead to a higher awareness of the historical sword as well.”

12. Where do you imagine the reproduction sword industry will be in 10 years? What developments do you anticipate, or would you like to see?

“Something that feels less encouraging is that so many enthusiasts are not willing to accept that quality products will inevitably cost more than cheap versions. Cheap versions mean that compromises are made, corners cut and/or that very cheap labor is used. Despite what marketing makes out, such “swords” are as a rule very far from the real thing.

It is a common expression among customers that a low cost sword can be “good value for the money.” It seems customers are still willing to compromise as long as they get a “good deal”. The urge to collect many swords invite enthusiasts to spend their money on several low quality items, rather than select fewer and better products: going for volume rather than content. I cannot help but think that a pile of horseshit, no matter how big, will never equal a slice of apple pie.

It is perhaps rather arrogant of me to think like this, but today information about swords is abundantly available on the Internet. New titles on historical swordsmanship are also being printed each year. My hope is that the increasing availability of information in time will lead to more educated customers, who are more selective in their choice of swords. By investing in high quality work customers support craftsmen who dedicate their life to the learning of the craft and study of swords. By going the cheaper route buying cheap compromises, customers will actually undermine the existence of quality conscious craftsmen. It is perhaps rather arrogant of me to think like this, but today information about swords is abundantly available on the Internet. New titles on historical swordsmanship are also being printed each year. My hope is that the increasing availability of information in time will lead to more educated customers, who are more selective in their choice of swords. By investing in high quality work customers support craftsmen who dedicate their life to the learning of the craft and study of swords. By going the cheaper route buying cheap compromises, customers will actually undermine the existence of quality conscious craftsmen.

All that aside, I think there is room for all levels of quality and all types of products on the market. We must not forget that those producing the really large quantities of so-called “swords” are aiming at the tourist trade and decorative market by producing ‘Sword Like Objects’ (SLO’s). These products are made and sold in the quantities of thousands upon thousands each year. Most are low cost and cheap in all meanings of the word, but quite a few will demand prices that is comparable to or even exceed the price of quality production swords. It is really just a clever way of selling lengths of steel to a very high price by alluring to the mystique of the sword.

Let us consider this fact: the interest in swords is so strong that thousands of customers each year willingly spend thousands of dollars on products that are obviously very far from true swords. The enormous sales of SLO’s results from massive marketing, exposure in shops, easy availability and, perhaps not least, a low level of awareness among customers.

This is actually very good news. If quality conscious custom smiths and small-scale production companies work together in educating customers, it opens very interesting possibilities. I firmly believe that many of those that buy gaudy stainless-steel decorative swords today would rather own a finely balanced, beautifully crafted sword if they only knew where to get it. If just a few percent of the customers who readily spend their money on expensive and glittering lengths of stainless-steel learn about the alternatives, there is plenty of work for those making quality swords. This is actually very good news. If quality conscious custom smiths and small-scale production companies work together in educating customers, it opens very interesting possibilities. I firmly believe that many of those that buy gaudy stainless-steel decorative swords today would rather own a finely balanced, beautifully crafted sword if they only knew where to get it. If just a few percent of the customers who readily spend their money on expensive and glittering lengths of stainless-steel learn about the alternatives, there is plenty of work for those making quality swords.

As the market for swords matures, we will see more martial arts practitioners emerging that have a well-developed taste in, and a deep knowledge about the European sword. This is another possibility for the makers of swords. Both small scale producers and custom smiths will be able to venture into more unusual expressions of the historical sword. We might also see makers dedicated to the possibilities of the contemporary sword get a wider recognition of their work on the collector market.”

13. How many expert swordsmiths of top notch artistry and accuracy would you say there are in Europe at present? 13. How many expert swordsmiths of top notch artistry and accuracy would you say there are in Europe at present?

“Difficult to say, really. I am certain there are a few around that have not yet been recognized by the public. I do not attend many shows (and I think this is true with most swordsmiths), so my own knowledge of European makers is only from what is obvious on the Internet, or those very few I have met. At any knife show there might be only one or two makers specializing in swords if even that many. A few makers will exhibit a sword or two as a central piece on their tables, but very few dedicate themselves fully and only to the craft of sword making. Most swords seen at knife shows are really just over sized knives.

There will never be many who dedicate themselves to this craft, but the number might be growing. Information on the Internet, published research and books/articles on the craft is getting more accessible and that helps new aspiring makers to achieve interesting results. At present, I think there might be just a handful of custom smiths who dedicate themselves full time to the making of swords. All of those would approach the craft in their very personal way, so it is difficult to compare their work. It is rare to see full-time makers dedicating much time to original research, since that eats away from available work time. It is difficult to charge customers for anything else but the time spent in the smithy making swords, so all work done in documentation and research needs to be funded by yourself.”

14. Are there any observations you could offer on the effects real swords had on targets? 14. Are there any observations you could offer on the effects real swords had on targets?

“The bones found in mass graves tell a very gruesome tale about the effect of sharp edges of swords and axes. My impression is that it is a very good idea to wear some kind of armor when you are about to be exposed to enemies that wield sharp swords with ill intent. Most sword types have evolved to be effective when put to a specific tactical use against opponents with certain defensive equipment. Either to directly penetrate armor in some way (not the most common solution) or just being able to survive a reasonable amount of abuse until an effective hit is scored.

From testing swords on realistic targets (simulating flesh and bone) I have seen that it is often more a matter of speed and precision, than brute force. When discussing the performance of swords, their ability to thrust and cleave, we often forget to put this in a proper perspective. The most efficient cutter is not always the most efficient sword. If raw cutting power is what we strive for, then most swords through the ages would have looked like executioners swords: broad and fairly heavy with a thin cutting section perfectly balanced to deliver a single powerful and precisely aimed cut. An executioner’s sword is not a really good weapon however; it is a specialized tool to end the life of a human being by the removal of the head. Its design does not offer the agility and maneuverability needed to be used in fighting.

All sword types are to some extent compromises between conflicting characteristics. A very stiff and rather narrow sword that is perfect for the techniques of Talhoffer and Fiore cannot offer the same cutting power as a bold, broad type XIIIa sword of war. The big war sword will not be as quick and tight in handling as the stiff, slim and pointy type XVa. All sword types are to some extent compromises between conflicting characteristics. A very stiff and rather narrow sword that is perfect for the techniques of Talhoffer and Fiore cannot offer the same cutting power as a bold, broad type XIIIa sword of war. The big war sword will not be as quick and tight in handling as the stiff, slim and pointy type XVa.

No one in their right mind will expect a slim 16th C cut-and-thrust sword to have the same cleaving power as a broad type X of the 10th century (both are very effective designs however.) The quickness of the slim cut-and-thrust cannot be fully exploited by a man in mail hauberk carrying a large shield. The blade he carries is a tool developed to deal with such defenses in the most expedient manner according to the given circumstances. We need to put different types of swords in their proper perspective to understand their use and potential. We cannot expect every type of sword to perform the same at the test-cutting stand.”

15. What advice do you have to offer the young fledging novice hoping to begin learning the craft of historical swordsmithing for fun? 15. What advice do you have to offer the young fledging novice hoping to begin learning the craft of historical swordsmithing for fun?

“First start with small projects to learn the various aspects of the craft. By making knives and daggers it is possible to develop skills in forging, heat treating, grinding and polishing and cutlery work. I think you sooner or later will need to study historical swords. There is really no way around this. By reading about swords and sword-making in books and digest information available on the internet you can pick up many important things, but you really need to get a personal experience by handling the real stuff to develop an understanding of the full potential of the historical sword.”

16. Aren’t razor sharp edges necessarily thin edges, and therefore, somewhat fragile? 16. Aren’t razor sharp edges necessarily thin edges, and therefore, somewhat fragile?

“The term ‘razor sharp’ can be confusing. It is often used to describe something that is really scary sharp without actually meaning it has the edge of a straight razor knife. This makes it difficult to answer the question without causing further confusion. Words are not so helpful in describing sharpness, as the reading is so much influenced by the mindset of the reader. That is cause for much misunderstanding and frustration when trying to communicate this via texts.”

17. Do historical Medieval and Renaissance sword specimens have edges razor like such as on modern fighting knives?

“No. Still, historical swords in mint condition can sport an edge geometry and sharpness that is finer than many modern pocketknives (finer as in crisper, thinner and more defined). Imagine a filet knife with edges sharpened like that of an axe. “No. Still, historical swords in mint condition can sport an edge geometry and sharpness that is finer than many modern pocketknives (finer as in crisper, thinner and more defined). Imagine a filet knife with edges sharpened like that of an axe.

On larger, more massive swords you might find edges that are less acute. They are still sharp but shaped with a blunter edge angle in the final sharpening. A sword with such an edge can still cut very well when used by someone that knows how to cut. A thin and fine edge will cut with effortless efficiency, but demands that the swordsman is mindful of where and how he places his cuts if he is to avoid nicks in the edge. Such a blade will not rely on power, but rather quickness and precision.

Looking at original swords we often see nicks and other damage, or the traces of re-sharpening. This is all in the life of a sword. Just like an experienced swordsman can carry scars to tell of the fights he has survived, a well-used sword will often have nicks and minor damages.

We must not forget that a sword is just like any tool: it takes a degree of awareness and skill to use effectively. This aspect is difficult to include in the modern study of swordsmanship. Nonetheless, we have to try.”

18. Can you really re-forge a broken or damaged sword blade and how practical would doing so be? 18. Can you really re-forge a broken or damaged sword blade and how practical would doing so be?

“I think the most practical way was rather to reuse broken or heavily damaged blades by welding them together into billets that then would be forged out to new blades.”

19. How long have you been involved in living-history reenactment and how has this influenced or affected your swordmaking?

“I started visiting the Medieval festival of Visby [off Sweden] many years ago (15 years, 18 years?) and my interest has evolved since then. Most important to me has been the friends I’ve met doing this. Many are skilled craftsmen on a hobby basis, creating beautiful work in metal, wood and leather. Their dedication to research and historical accuracy is always very inspiring.

I am (occasional) member of a Stockholm group (Guild of Saint Olaf) focusing on the late 15th century. This group has connections to the international European group of Company of Sainte George. It is a privilege as a member to benefit from the work of many others and see how ideas and efforts combine in a magic experience of traveling back in time. This brings a wider perspective to the study of arms and armour. To do halberd drills in formation wearing half armor with a hand and a half sword strapped to my waist was a learning experience…I would not recommend that combination of weapons if you want to avoid ugly halberd accidents in your own ranks…Or perhaps it is another case of more training needed on my part?”

20. What’s your current involvement with Albion Swords? 20. What’s your current involvement with Albion Swords?

“I develop original designs for their Next Generation Line, reconstructions of specific originals for the Museum Line and also consult on various production issues. In some cases I help find literature or documentation that is then further developed into products by the artisans at Albion. I visit the workshops two times each year to spend some intensive two or three weeks.

The designs I develop are either reconstructions of specific historical swords (to be included in the Museum Line) or swords that are good representations of historical types, based on data from several original specimens. My ambition is that the resulting sword shall exhibit the same character as the originals I’ve seen and documented. For the generic representations I use both measurements from documented originals as well as applying principles for proportions that can be seen in many swords of the same type. This applies to everything from overall shape and character down to variations in cross section and distal taper. We can now see the result of work that begun in 2001 and this is to me very exiting.”

21. Do you have any coming plans you can share about future projects?

“Presently, I think the development at Albion Armorers is very exiting. We have worked countless hours in development, and now swords are being delivered to customers. The product line is constantly expanding, including new styles, types and time periods. It is exiting to see the possibilities for a production line that make use of not only specific measurements of originals, but also ancient principles of proportions. Both the Museum Line and the Next Generation line are going to see new additions in the coming year. Regarding my own sword making, I look forward to realizing some plans on early Iron Age and early medieval swords in my own smithy. The Bronze Age and Celtic Iron Age becomes steadily more interesting to me, but there will always be new versions of the classic longsword to explore. I make some experiments with bronze blades and also spend some time exploring pattern welding. We shall see what the results of this might be.”

Photos by Lutz Hoffmeister. All rights reserved.

For available commercial models of Peter’s work see: www.Albion-Swords.com |