The

Importance of Studying Fechtbücher

By

Bartholomew Walczak, By

Bartholomew Walczak,

BEN, ARMA Cracow

The subject of

historical European martial arts as been so far addressed only marginally. These

traditions disappeared and in contrast to Eastern Martial Arts, and with the sole

exception of wrestling, they cannot be recreated on the base of any present combatitive

sport. The Fechtschulen (fight schools) and Fechtmeisteren (fight masters) no longer exist, and

we do not have anyone like the Eastern sensei

who could teach us how to fight with a sword,

cutlass, or halberd. The only reasonable option for the reconstruction of historical

European martial arts is the study of old Fechtbücher

– fighting treatises – and applying the knowledge contained therein in modern

practice.

Background Background

Historical

European martial arts reconstruction has its roots in the

19th century interest in the ideas of knighthood

and nobility. Historic books by famous authors (among them

Sir Walter Scott and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) had inspired

the English nobles to organise a tournament in Eglinton

in the year 1839, where the participants could try their

skills in combat. The re-enactment groups who mainly deal

with the romantic aspects of knighthood have recently undergone

another renaissance. However instead of the academic sources

they very often rely on the stereotypes of their own visions

of the Middle Ages and the ways of wielding these weapons.

Their cause is noble but the lack of availability of the

sources and mostly playful attitude often lead them to a

dead-end as far as the martial arts are concerned.

Apparently

the first attempts of the reconstruction has been made as

early as 1890s when Sir Egerton Castle and Sir Captain Alfred

Hutton (among others) presented their analyses of “ancient

weapons” to the general public. We do not possess the

exact account of the events in question, yet from both Castle’s

and Hutton’s works we can tell that the “first

steps” in the HEMA reconstruction were full of errors

and misconceptions. The events were described in more detail

in articles by John Clements “Historical

Fencing Studies - The British Legacy” and Tony

Wolf “The Grand Assault at Arms” (available at

http://ejmas.com/jmanly/).

The

interest in HEMA has existed for over a century, yet in

fact it was the Internet which brought the researchers (both

scholars and hobbyists) together. Before that the separate

groups or “reconstructors”, historians and archaeologists

were virtually unknown and worked on their own. Nowadays

the groups like the Association for

Renaissance Martial Arts,

Chicago Swordplay Guild, Academy of European Medieval Martial

Arts, the Exiles and many others have many active members

and communicate with each other. The reconstruction has

became a goal for many researchers, both hobbyists and scholars.

Many groups have approached the subject from different angles

and mostly independently until the advent of the internet.

The mutual contact among so many resulted in the application

of more academic methods and a real possibility for the

reconstruction of European martial arts.

Problems

of Reconstruction

Generally

there are two accepted methods used for the reconstruction

of the tools and the ways of using them. The first is to

analyse the available sources and to try to reconstruct

the subject, as it was the case with historical instruments,

among which no piece has survived that could be played with.

The other one is to use a surviving piece in the environment

which is as close to the original one as possible. This

kind of method was used, for example, to check the power

of an arrow shot with the use of a long bow. Generally

there are two accepted methods used for the reconstruction

of the tools and the ways of using them. The first is to

analyse the available sources and to try to reconstruct

the subject, as it was the case with historical instruments,

among which no piece has survived that could be played with.

The other one is to use a surviving piece in the environment

which is as close to the original one as possible. This

kind of method was used, for example, to check the power

of an arrow shot with the use of a long bow.

Both methods have

their advantages and disadvantages, which should be discussed in the context of historical

European martial arts. The source analysis gives us a theoretical knowledge on how the

weapon could have been used in the past. However, after sources are analysed, we are still

left with many questions and then the experimental method comes into play. Similar to

historical dancing manuals, with martial arts one should try to apply knowledge in

practice. The most extreme variant of this method is when one has no sources, and has to

analyse the tool in order to guess its possible usage. Afterwards is the time for a

testing phase, where one should remember to create an environment as closely resembling

the original one as possible.

As

far as the martial arts are concerned, this condition is

almost impossible to fulfill. The weapons were used to maim

and kill well-skilled opponents in a life-threatening situation.

For obvious reasons the experimental method will only be

an approximation, which has an impact on the results. The

lack of sources is the reason for a natural tendency among

researchers to look for analogies in using tools among other

similar and well-known objects. This leads to many misunderstandings

and to the cardinal error often made by amateur researchers:

adapting the tool to the method. Most of the errors committed

in the early stages of reconstruction fall into this category.

It is a truism to say that such analysis can hardly lead

to the right conclusions.

Along with the

amount of knowledge acquired, there grows an awareness of the way of using certain tools.

One can check various techniques, and slowly gain comprehension of the way in which it was

done before. By using original surviving tools or close replicas of them one can find

answers not given in the sources (for example, fundamental information like the speed and

force of a sword cut). Only by joining the two methods: analysis and experiment, can one

learn about the whole of martial arts.

Drawbacks

of Treatises

The historical combat

treatises were addressed mainly towards the nobility, and later on, along with the

increasing importance of the city statesmen, also to some important officials. Johannes

Liechtenauer leaves no doubt as to whom he speaks to, beginning his verses with:

“Young knight learn to love the God and honour the ladies and your fame will

grow.”

Similarly, the anonymous author of the French Le

Jeu De La Hache writes: “And for this, let every man, noble of body and courage,

naturally desire to exercise […] principally in the noble feat of arms.”

Fiore dei Liberi in the prologue mentions that he would not like his art to be spread

among the people who “would not use it properly.”

His follower, Filippo Vadi, takes it even further: “…never, by no means, this art and doctrine should fall in

the hands of unrefined and low born men.” The historical combat

treatises were addressed mainly towards the nobility, and later on, along with the

increasing importance of the city statesmen, also to some important officials. Johannes

Liechtenauer leaves no doubt as to whom he speaks to, beginning his verses with:

“Young knight learn to love the God and honour the ladies and your fame will

grow.”

Similarly, the anonymous author of the French Le

Jeu De La Hache writes: “And for this, let every man, noble of body and courage,

naturally desire to exercise […] principally in the noble feat of arms.”

Fiore dei Liberi in the prologue mentions that he would not like his art to be spread

among the people who “would not use it properly.”

His follower, Filippo Vadi, takes it even further: “…never, by no means, this art and doctrine should fall in

the hands of unrefined and low born men.”

This elitism is

the main argument against the treatises, but there are many facts which stand against it:

the masters possessed the awareness of the existence both of the lower classes and their

own ways of fighting. Fiore mentions: “[…] Kings, Princes, Counts, generals,

earls and clergy people are qualified for the duels.” Vadi says: “For this reason I rightly tell you that they [the low born

men] are in every way alien to this science, while the opposite is true, in my opinion,

for anybody of perspicacious talent and lovely limbs, as are courtesans, scholars, barons,

princes, dukes and kings.” The author of Le Jeu De La Hache adds: “[…] the Axe-play is honourable and

profitable for the preservation of a body noble or non-noble.”

Surely,

the lower classes were looked down upon, which is confirmed

by many various quotations, for example in Vadi: “…Heaven

did not generate these men [low born], unrefined and without

wit or skill, and without any agility, but they were rather

generated as unreasonable animals, only able to bear burdens

and to do vile and unrefined works.”

or in von Danzig calling the Zornhaw

“a bad peasant blow”,

because this was the way in which an unskilled peasant would

attack. Similarly Liechtenauer’s scorn for the masters

of lower standing (and lesser skill) can be seen in him

calling them Leychmeistere

– the dance masters. However it can be sure that the

lower classes practised their own forms of the martial arts,

perhaps more sport-like than the upper classes. Interestingly

both in the literature and in the chronicles one can find

remarks about the commoners beating the knights in wrestling,

although sometimes it is clearly just a rhetorical figure,

symbol or a metaphor. The existence of the martial arts

similar to the Eastern kabudo also can be confirmed in Paulus Hector Mair’s treatise

which contains a section on the combat with a sickle and

a flail, which at first were peasant’s tools.

Undoubtedly

both the costs of creating the treatises and common illiteracy

were one of the main reasons why during the Middle Ages

there didn’t exist books aimed at the lower classes.

During that time the oral tradition fulfilled a very important

role, so we can suspect that the lower classes gained their

knowledge in a practical manner. It does not mean that the

people who took part in battles were unskilled. Certainly

even the Leychmeisteren could teach something

to the commoners, and as we can learn from many other sources,

sword and buckler was quite a popular weapon also of the

lower classes.

The

lower classes rarely duelled, they were rather called to

arms for bigger skirmishes and battles, and in combat with

many opponents the tactics are much more important than

the number of known techniques. Most probably in the process

of teaching to fight, the number of techniques had less

importance than the ability to use them in the real combat.

Another

drawback of the treatises is that there are only 2 surviving

pieces from the 14th century, and none earlier.

If one wants to reconstruct the 11th or 12th

century sword and shield combat, he needs to extrapolate

from the sources as late as the Renaissance. Most interestingly,

Medieval treatises do not deal with sword and shield at

all (only the buckler and the large German duelling shields

or thin knight’s shields used mainly for duelling).

Dr. Sydney Anglo proposes that the medieval Fechtbücher should in fact be treated

as the advent of the Renaissance. However one should note

that the techniques contained therein were used during the

14th and 15th centuries therefore

calling them “Renaissance Martial Arts” is maybe

a little bit off. However the distinction between the Martial

Arts of Middle Ages and those of Renaissance can be hard

at best since most of the schools continued and evolved

through the 15th-16th centuries.

The

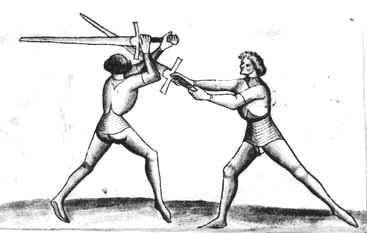

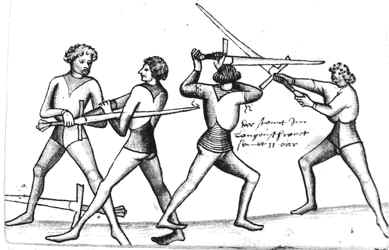

next problem with treatises is of another kind. Every master

describes the techniques in his own way. For example even

the pupils of Johannes Liechtenauer give us different interpretations

of his verses, as it can be seen in treatises by Hanko Döbringer,

Peter von Danzig and Sigmund Ringeck. When one adds to it

possible errors of the scribe (like switching the descriptions

of pictures in the Codex Wallerstein or adding verses on

the margins as in Döbringer), artwork which sometimes doesn’t

fit the text, new vocabulary, sometimes vague and even cryptic

descriptions (Talhoffer), quite illegible handwriting (Paulus

Hector Mair), lack of the rules of orthography, the state

of some surviving pieces (the so-called “Solothurner

Fechtbuch”), and finally the notion that most of them

were never intended as manuals but a form of self-presentation

or discussion, one can see that the deciphering of the treatise

becomes a very hard task.

At

the end one should add that the Medieval masters fully understood

both the complication of their art: “…this art

is so complicated that it can hardly be remembered without

the help of books or treatises…” (says Fiore dei

Liberi), and the limitations of the books: “A man cannot

explain combat as clearly by speaking and writing as he

can teach and show with the hands.” (concludes Döbringer).

Other

Possible Sources

![Triumphzug1]Stang.JPG (22033 bytes)](Triumphzug1Stang.JPG) Among other sources one could count the chronicles.

However the accurateness of the narrative sources was very much criticised by Sydney Anglo

in his book “Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe”. He quoted the descriptions of

two fights: the duel between Anthony Woodville and Bastard of Burgundy (1467) given by

four various witnesses, and another duel between Bayard and Alonzo de Sotomayore (1503)

described by three various people. The differences between the

actual relations show that we cannot depend on the chronicles as the primary sources in

the reconstruction of the European Medieval Martial Arts. Among other sources one could count the chronicles.

However the accurateness of the narrative sources was very much criticised by Sydney Anglo

in his book “Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe”. He quoted the descriptions of

two fights: the duel between Anthony Woodville and Bastard of Burgundy (1467) given by

four various witnesses, and another duel between Bayard and Alonzo de Sotomayore (1503)

described by three various people. The differences between the

actual relations show that we cannot depend on the chronicles as the primary sources in

the reconstruction of the European Medieval Martial Arts.

The

romances and chanson de geste should be dealt

with separately. Some details of using various weapons can

be found even in Nordic Sagas.

The descriptions of feats of arms however are much too exaggerated

and heroic. The blows given by combatants can cut a man

in half along with his horse.

The descriptions often lack any details about the exact

ways of fighting. The author of a romance was usually interested

in the effect inflicted upon the reader than the exact depictions

of combats. However sometimes a few correct conclusions

could be made when compared to other sources – like

cutting at opponent’s legs often found in the Sagas

and confirmed later on by Medieval archaeological finds.

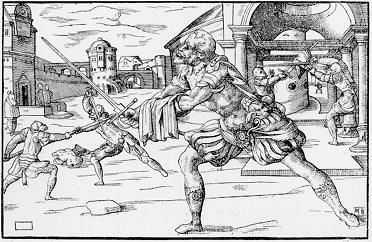

Up

until recently (and unfortunately sometimes even still)

the significance of contemporary illuminations and artwork

has been very much underrated. The prevailing opinion that

the art lacked realism hopefully is losing its ground. It

turns out that very often those depictions seem very similar

to the ones found in the treatises. Closer examination of

these sources – very numerous and often ignored –

can help us to place the martial arts in the proper social

and cultural context.

The

last possible source could be the forensics from the excavations

of the battlefields such as Towton and Wisby. They can give

us very interesting information about the injuries from

the contemporary weapons and in connection with the analysis

of treatises they can be very helpful in the reconstruction

of the actual combat. They only drawbacks are that they

can show us only the bone injuries and we can never be sure

of the actual situation of when and how the wounds were

received. The main example could be the skull which was

three times shot with a crossbow bolt which brought a lot

of speculations. Also such rich finds as Wisby and Towton

are quite rare.

As

one can see, we cannot rely solely on the secondary sources.

They supply us with the social and cultural context but

not the exact ways of handling the weapons. What is found

in the texts, illustrations and excavations we must consider

in the context of the treatises. The opposite is also true

– we must look at the Fechtbücher

in the proper cultural context and not draw incorrect conclusions.

Available

Treatises

The direct instructions in the form of

fighting treatises started to appear at the end of the 13th century. The oldest

known surviving piece is the I.33 Manuscript held in Royal Armouries in Leeds, which

describes the combat with sword and buckler. The work of brothers Del Serpente, which has

still not been found, dates at the same period of time however Dr Anglo’s

investigation casts doubt on its existence. It seems that those two books are somewhat

unique in their own time, because the next surviving manuscript is dated at 1389 and was

written by a priest, Hanko Döbringer, a pupil to Johannes Liechtenauer and is mainly a

discussion between the author and leychmeistere. The direct instructions in the form of

fighting treatises started to appear at the end of the 13th century. The oldest

known surviving piece is the I.33 Manuscript held in Royal Armouries in Leeds, which

describes the combat with sword and buckler. The work of brothers Del Serpente, which has

still not been found, dates at the same period of time however Dr Anglo’s

investigation casts doubt on its existence. It seems that those two books are somewhat

unique in their own time, because the next surviving manuscript is dated at 1389 and was

written by a priest, Hanko Döbringer, a pupil to Johannes Liechtenauer and is mainly a

discussion between the author and leychmeistere.

The

end of the 14th and the beginning of the 15th

centuries are the times of the masters who systematised

the martial arts: Johannes Liechtenauer (a long sword and

wrestling), Andrew Legnitzer (a spear), Ott Jud (wrestling)

and Fiore dei Liberi (a complete fighting system). From

among them Liechtenauer seems to be especially important,

since from him comes the German tradition of the long sword

combat widely copied almost without changes and developed

in the 15th century treatises of Peter von Danzig,

Sigmund Ringeck, and in the later anonymous “Goliath”

and Jörg Wilhalm, finishing at Joachim Meyer who however

changed it considerably. This tradition has been described

in detail in a few academic works. Fiore dei

Liberi seems to be a father of the Italian tradition which

starts with his “Flos Duellatorum” (3 different

editions) and is continued by Filippo Vadi and later on

by Achille Marozzo (“Opera Nova”) and Manciolino.

This tradition awaits more detailed examination.

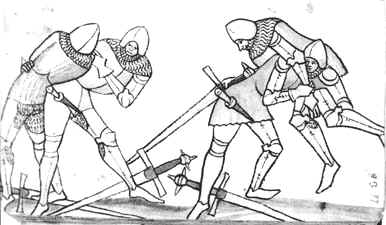

I.33

is interesting because of its uniqueness (as one of the

few which teaches how to fight with the sword and buckler).

Worth noticing among the 15th century sources are also “Gladiatoria”

which deals with armoured combat, possibly containing Liechtenauer’s

advice on the topic, and the French “Le Jeu De La Hache”,

which describes the way to fight with a pole-axe. Lecküchner’s

treatise on messer seems to contain the widest

spectrum of the techniques with this weapon. Hans Talhoffer,

although containing the Ott’s wrestling and interesting

pole-axe and dagger sections seems to be much overrated,

being very cryptic and containing little practical advice.

Unfortunately this treatise is the most exploited one and

often used as a sole source which leads to many misunderstandings

in HEMA reconstruction.

Other

sources include: Codex Wallerstein, Hans Czynner, Paulus

Kal (rival to Talhoffer), and Sigmund Schinning (contains

unorthodox Liechtenauer glosa). There exist also some French

sources which have not yet been fully investigated. Also

two English manuscripts: Harleian MS 3542 and Additional

MS 39564 prove to be very hard to translate into Modern

English and to interpret. Recently there has been found

a new short German manuscript which seems not to follow

Liechtenauer’s tradition.

From among the

Renaissance manuscripts the continuation of Medieval traditions can be found in

“Goliath”, Jörg Wilhalm, Achille Marozzo and Manciolino as mentioned earlier.

According to Dr. Anglo, Pietro Monte (the very end of the 15th century), a

Spanish master, described medieval techniques. Also George Silver’s Brief Instruction on my Paradoxes of Defence of

1599 contains some valuable advice and its sword and buckler has distinctive connections

to the I.33. Albrecht Dürer – a

famous painter from the early 1500s– deals with medieval combat too. Worth noticing

is the 1200 pages long compilation made by Paulus Hector Mair, a burgher obsessed with the

martial arts.

Those

works up until today comprise most of the Medieval Martial

Arts sources available to us. A wider description of medieval

fighting treatises can be found in the articles by S. Matthew

Galas “Setting the Record Straight: The Art of the

Sword in Medieval Europe” (available through www.theARMA.org)

and “Kindred Spirits”. See also the piece on “Renaissance

Martial Arts Literature” (also at www.theARMA.org).

German treatises were described in detail by Hans-Peter

Hils in his work “Meister Johann Liechtenauer’s

Kunst des langen Schwertes

(“Art of the Long-Sword”).

As

one can see, the number of sources is vast. Some of them

teach from the start (Liberi) and others contain only some

selection of the techniques (Codex Wallerstein). Each of

them should be looked at in detail and interpreted in order

to better understand the way of handling weapons.

Closing

Remarks

The

ideal to which each serious student of historical European

martial arts should strive is to read and comprehend at

least a few of the most important treatises, handle original

surviving pieces, fight with various partners using excellent

replica weapons, and take part in bigger mock combat skirmishes.

So far the sources are mostly hard to obtain, written in

Latin, Old German or Old French, which are rather unknown

to people not dealing with the history or philology. This

situation hopefully changes for the better, because of the

growing interest in the manuscripts and awareness of the

existence of Western Martial Arts. There appear to be more

interpretations and translations. However the weapon replicas

often are still nowhere near the quality of the originals

and handling the originals is restricted. The

ideal to which each serious student of historical European

martial arts should strive is to read and comprehend at

least a few of the most important treatises, handle original

surviving pieces, fight with various partners using excellent

replica weapons, and take part in bigger mock combat skirmishes.

So far the sources are mostly hard to obtain, written in

Latin, Old German or Old French, which are rather unknown

to people not dealing with the history or philology. This

situation hopefully changes for the better, because of the

growing interest in the manuscripts and awareness of the

existence of Western Martial Arts. There appear to be more

interpretations and translations. However the weapon replicas

often are still nowhere near the quality of the originals

and handling the originals is restricted.

The

reconstruction is a very hard task which demands a lot of

time and work. Not many can devote so much. However the

lack of time should not be an excuse to dismiss the sources

in favour of the “pure” experimental method. By

our present knowledge we can tell that without the sources

this method rarely succeeds. Regardless of their drawbacks

(true or suspected elitism, limited number of techniques,

possible randomness of the surviving pieces), the treatises

are the only plausible source, what Sydney Anglo strongly

emphasizes in his book. The historical European martial

arts were so complex and diverse that there is no real serious

alternative to the studying of the Fechtbücher.

In

time, maybe there will appear modern schools of European

martial arts, and people attending there will learn the

techniques from the “second hand”, although the

teacher (or “master”) should legitimize himself

with the deep knowledge of the subject. Only then we will

be able to speak about the true historical European martial

arts. Before that though we have a long way ahead of us.

About the author: Bartlomiej Walczak, one of the founders of Brotherhood

of the Eagle's Nests ARMA Study Group, has

been a HEMA practitioner since 1998. He started with a simple

reenactment, and the day he discovered the Fechtbücher

was his real enlightenment. Passing through various stages

of misinterpreting the sources he has only recently “started

touching the truth” and he hopes to carry on with more

serious research.

Footnotes

- The author used the translation of

selected parts of Hanko Döbringer's treatise by Grzegorz Zabinski.

- The translation of "Le Jeu De La Hache" by Dr. Sydney

Anglo.

- The translation of Fiore dei

Liberi's "Flos Duellatorum" by Royal Armouries in Leeds.

- The translation of Filipo Vadi's

treatise prologue by Luca Porzio.

- The translation of selected pieces

of Peter von Danzig by Grzegorz Zabinsky.

- See eg. Chaucer description of the

Miller.

- This subject has been addressed in a wider scope

by J. Clements in his article "One against many",

and Mark Bertrand in his article "Tactical Swordsmanship".

- The subject of other possible

sources for reconstruction of Medieval Martial Arts has been dealt in detail in the book

by Dr Sydney Anglo "Martial Arts in the Renaissance Europe".

- Anglo Sydney, "Martial Arts

in the Renaissance Europe", pp. 18-20

- Oakeshott Ewartt,

"Archaeology of Weapons"

- see eg. Chanson de Roland.

- For the possible mistakes one can

make while interpreting manuscripts without their cultural context see Christopher

Amberger's article "Playing by the Rules".

- Master Johannes Liechtenauer used

this term to denote swordsmen who deal only with shows, not the real swordfighting.

- Among them the most important ones

include Hans-Peter Hils "Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des langen

Schwertes" and Martin Wierschin "Meister Johann Liechtenauers Kunst des

Fechtens".

- Galas S. Matthew Kindred Spirits.

The art of the sword in Germany and Japan, Journal of Asian Martial Arts, VI (1997), pp.

20-46.

Bibliography

1.

Anglo Sydney, Martial Arts of the Renaissance

Europe

2.

Amberger Christopher, The Secret History of the

Sword

- Anonymous, Chanson de Roland

- Chaucer Geoffrey, Canterburry Tales

- Clements John, Medieval Swordsmanship

- Clements John, Renaissance Swordsmanship

- Cvet David, The Art of the Long Sword Combat

- Hils Hans-Peter, Meister Johann Liechtenauers

Kunst des langen Schwertes

- Oakeshott Ewartt, Archaeology of Weapons

- Wierschin Martin, Meister Johann Liechtenauers

Kunst des Fechtens

WWW Sites of Interest:

- Academy of European Medieval Martial

Arts

- The Association for Renaissance Martial

Arts

- Chicago Swordplay Guild

- Chronique

- The Exiles CMMA

- Secret History of the Sword

|