Legs,

Wounds, and Standing Fights in Historical Fencing

By John Clements

ARMA Director

"A full blow upon the neck,

shoulder, arm, or leg, endangers life, cuts off the veins, muscles,

and sinews, perishes the bones. These wounds made by the blow, in

respect of perfect healing, are the loss of limbs, or maims incurable

forever."

- George Silver, Paradoxes of Defence, 1598

Frequently,

I’m asked by practitioners and members to comment further upon

certain unfortunate practices within versions of historical-sport

fencing games: that of electing to reflect leg and hips strikes so

as to require combatants to drop down in order to continue to play.

I refuse these requests out of hand, as they are not germane to ARMA’s

Study Approach. When I am however asked to help provide documented

evidence of the effects of leg wounds in Medieval and Renaissance

combat and their meaning in historical fencing study today, I cannot

refuse. Frequently,

I’m asked by practitioners and members to comment further upon

certain unfortunate practices within versions of historical-sport

fencing games: that of electing to reflect leg and hips strikes so

as to require combatants to drop down in order to continue to play.

I refuse these requests out of hand, as they are not germane to ARMA’s

Study Approach. When I am however asked to help provide documented

evidence of the effects of leg wounds in Medieval and Renaissance

combat and their meaning in historical fencing study today, I cannot

refuse.

Let’s take a brief look then at just what historical accounts

and descriptions of combats actually tell us about leg wounds and

standing up in fighting.

The

ancient author Dionysius of Halicarnassus wrote of a battle in 436

BC between the Romans and the Gauls, describing how with the short

gladius the legionnaires, "would cut the tendons of their [enemies]

knees and topple them to the ground". In the 1300s, William

of Apulia writes of battle describing "Feet lopped off at the

knee and ankle" and well known are the skeletal remains from

the battle of Wisby in 1361 on the Baltic isle of Gotland off the

coast of Sweden. Excavations and forensic examinations of the remains

of more than one thousand of the fallen fighters reveal that

more than 400 of just over 1000 fighters suffered serious

leg wounds. Bones were sheared through or cracked and shattered, others

were cut to through teh muscle and tissue. Several victims even loss

both legs completely. (Thordeman, p. 167-172). The

ancient author Dionysius of Halicarnassus wrote of a battle in 436

BC between the Romans and the Gauls, describing how with the short

gladius the legionnaires, "would cut the tendons of their [enemies]

knees and topple them to the ground". In the 1300s, William

of Apulia writes of battle describing "Feet lopped off at the

knee and ankle" and well known are the skeletal remains from

the battle of Wisby in 1361 on the Baltic isle of Gotland off the

coast of Sweden. Excavations and forensic examinations of the remains

of more than one thousand of the fallen fighters reveal that

more than 400 of just over 1000 fighters suffered serious

leg wounds. Bones were sheared through or cracked and shattered, others

were cut to through teh muscle and tissue. Several victims even loss

both legs completely. (Thordeman, p. 167-172).

It

was even common in 15th century Spain for monetary compensation to

be paid to knights for wounds received in combat and "…the

grand sum of 120 maravedís was recommended for those who lost …a

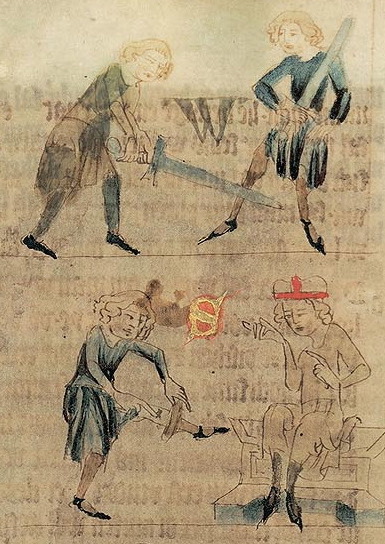

leg below the knee." In the Fechtbuch

illustrations of Joerg Wilhalm from 1523, there are even color depictions

of fighters clearly bleeding from minor wounds to their calves during

practice with blunt great-swords. One page also shows three

separate stop-thrusts to the foot (in which the sword punctures the

armored sabaton in a splatter of bright red). The same manuscript

even shows an unarmored fighter continuing to practice with a bloodied

bandage on one of his bare calves. It

was even common in 15th century Spain for monetary compensation to

be paid to knights for wounds received in combat and "…the

grand sum of 120 maravedís was recommended for those who lost …a

leg below the knee." In the Fechtbuch

illustrations of Joerg Wilhalm from 1523, there are even color depictions

of fighters clearly bleeding from minor wounds to their calves during

practice with blunt great-swords. One page also shows three

separate stop-thrusts to the foot (in which the sword punctures the

armored sabaton in a splatter of bright red). The same manuscript

even shows an unarmored fighter continuing to practice with a bloodied

bandage on one of his bare calves.

Viking

Sagas are rich with accounts of leg blows and their effects. In the

13th century Kormak’s Saga, we read how "Ogmund whirled

about his sword swiftly and shifted it from hand to hand, and hewed

Asmund’s leg from under him." In Eyrbyggja Saga we

read how "Thorarin cut the leg from thorir at the thickest of

the calf" and how Steinthor "smote at Thorleif Kimbi, and

smote the leg from him below the knee..." From the Laxdaela

Saga there is the account of how "Kjartan cut off one leg

of Gudlaug above the knee, and that hurt was enough to cause death"

as well as how "Thorleik struck him with his sword, and it caught

him on the leg above the knee and cut off his leg, and he fell to

earth dead." From the 14th century Icelandic Grettir’s

Saga, we read of Onund and how a man "struck him and took

off his leg below the knee, disabling him at a blow." From Book

I of Saxo Grammaticus’ late 12th to early 13th century Nine

Books of the Danish History, we also read how against his opponent

one warrior "clove asunder his left arm and part of his left

side and his right foot". We then read how Horwendil fought Koller

"and at last hewed off his foot and drove him lifeless to the

ground." In all these examples, with a single heavy blow

from a single-hand cutting blade the unarmored leg is hewn from the

body and the victim is immediately incapacitated or killed. Viking

Sagas are rich with accounts of leg blows and their effects. In the

13th century Kormak’s Saga, we read how "Ogmund whirled

about his sword swiftly and shifted it from hand to hand, and hewed

Asmund’s leg from under him." In Eyrbyggja Saga we

read how "Thorarin cut the leg from thorir at the thickest of

the calf" and how Steinthor "smote at Thorleif Kimbi, and

smote the leg from him below the knee..." From the Laxdaela

Saga there is the account of how "Kjartan cut off one leg

of Gudlaug above the knee, and that hurt was enough to cause death"

as well as how "Thorleik struck him with his sword, and it caught

him on the leg above the knee and cut off his leg, and he fell to

earth dead." From the 14th century Icelandic Grettir’s

Saga, we read of Onund and how a man "struck him and took

off his leg below the knee, disabling him at a blow." From Book

I of Saxo Grammaticus’ late 12th to early 13th century Nine

Books of the Danish History, we also read how against his opponent

one warrior "clove asunder his left arm and part of his left

side and his right foot". We then read how Horwendil fought Koller

"and at last hewed off his foot and drove him lifeless to the

ground." In all these examples, with a single heavy blow

from a single-hand cutting blade the unarmored leg is hewn from the

body and the victim is immediately incapacitated or killed.

From the Gesta material of c.1125, we do read the folkloric

tale of the legendary Saxon hero, Hereward the Wake, who "called

his sword 'Brainbiter'" for "He could fight twelve people

at once with it!" In one likely apocryphal episode (Gesta section

XXXII) he fought an eminent knight in single combat, which would likely

have occurred in maile byrnies with sword and shield: "Hereward

drew from its sheath a second sword… and attacked his opponent

more vigorously. And at the first blow,  while

feigning an attack on the head, he struck the man in the middle of

his thigh. Still the soldier defended himself for some time on his

knees, declaring that for as long as there was life in him he would

never be willing to surrender or look beaten. Admiring which, Hereward

praised his bravery and courage and stopped attacking him, leaving

him and going on his way." This fictional tale says nothing of

the magnitude of the wound to the thigh and as Hereward seeks for

him to yield the soldier is only able to defend himself awhile -not

attack or strike back, just defend. From the leg blow the man is unable

to stand and falls downs to his knees, where, although he manages

to stay alive, he is unable to effectively fight, and Hereward, knowing

the man is clearly beaten, respects his refusal to surrender and so

simply walks away rather than finishing him off. Hereward knows he

can kill him easily enough… and that there is nothing to prevent

Hereward just walking away. while

feigning an attack on the head, he struck the man in the middle of

his thigh. Still the soldier defended himself for some time on his

knees, declaring that for as long as there was life in him he would

never be willing to surrender or look beaten. Admiring which, Hereward

praised his bravery and courage and stopped attacking him, leaving

him and going on his way." This fictional tale says nothing of

the magnitude of the wound to the thigh and as Hereward seeks for

him to yield the soldier is only able to defend himself awhile -not

attack or strike back, just defend. From the leg blow the man is unable

to stand and falls downs to his knees, where, although he manages

to stay alive, he is unable to effectively fight, and Hereward, knowing

the man is clearly beaten, respects his refusal to surrender and so

simply walks away rather than finishing him off. Hereward knows he

can kill him easily enough… and that there is nothing to prevent

Hereward just walking away.

In

1263 a chivalric combat occurred in Scotland between Sir Piers de

Curry and Andrew Nicolson. As the mounted Piers brandished his spear

at Nicolson, Nicolson charged Piers on foot and with his sword struck

a blow that severed Piers thigh from his body and killed him on the

spot. In the 1300s there was a combat between two Spanish captains

at Ferrara, in which: "the combatants being engaged, one of the

parties received a desperate wound, which occasioned such a loss of

blood that he sank to the ground; when his antagonist, according the

noble institutions of chivalry, rushed on him with the point of is

sword to his throat." The combat then ceased. In

1263 a chivalric combat occurred in Scotland between Sir Piers de

Curry and Andrew Nicolson. As the mounted Piers brandished his spear

at Nicolson, Nicolson charged Piers on foot and with his sword struck

a blow that severed Piers thigh from his body and killed him on the

spot. In the 1300s there was a combat between two Spanish captains

at Ferrara, in which: "the combatants being engaged, one of the

parties received a desperate wound, which occasioned such a loss of

blood that he sank to the ground; when his antagonist, according the

noble institutions of chivalry, rushed on him with the point of is

sword to his throat." The combat then ceased.

Hutton

recounts a fight in the 1400’s, as relayed by one Lindsay of

Pitscottie, between Sir Patrick Hamilton and a Dutch knight, Sir John

Cockbewis. "Then both the knightis alighted on thair foott, and

joyned pertlie togidder with rightawful countenance; each on stark

uther and foight the space of an hour with uncertaine victorie, quhill

at the last said Sir Patrick rusched rudlie upon the Duchman, and

strak him on his knies, and the Duchman being on his knies, the king

kest his hatt over the castle wall, and caused the judges to stay

and red thame; but the trumpeteris cryed out and soundit, saying the

victorie was Sir Patrickis." Once the combatant was down on his

knees, the fight was stopped. Hutton

recounts a fight in the 1400’s, as relayed by one Lindsay of

Pitscottie, between Sir Patrick Hamilton and a Dutch knight, Sir John

Cockbewis. "Then both the knightis alighted on thair foott, and

joyned pertlie togidder with rightawful countenance; each on stark

uther and foight the space of an hour with uncertaine victorie, quhill

at the last said Sir Patrick rusched rudlie upon the Duchman, and

strak him on his knies, and the Duchman being on his knies, the king

kest his hatt over the castle wall, and caused the judges to stay

and red thame; but the trumpeteris cryed out and soundit, saying the

victorie was Sir Patrickis." Once the combatant was down on his

knees, the fight was stopped.

While the idealized and often fantastical knightly combat in early

chivalric romances sometimes does provide clues to the reality of

such fighting, at other times however it represents something else

entirely. In the 12th century epic, Iwein (itself a German

version of Chrétien de Troyes' Arthurian epic Yvain)

by the Swabian knight and poet, Hartmann von Aue, we find the following

unusual comment regarding a description of two knights in single combat

with swords: 'They did not try to strike any blows below the knee

because they did not have any shields' (See Pincikowski in Classsen,

p. 105). However, from his translation work of this courtly literature,

medievalist Scott Pincikowski believes that there is no proof this

kind of statement was reflective of actual reality. Rather, he suggests

that such idealized conceptions of combat were an attempt by poets

at the time to offer chivalric knights a ritualized mode of behaving

that did not result in certain violent death or maiming to one another.

We have no way of knowing, he notes, to what degree such a statement

was followed by knights in the 11th and 12th centuries. But the very

fact that such an idea (i.e., hacking at shields and helms rather

than vulnerable legs) had to be put forward in early courtly literature

was, he feels, an indicator that it was not the norm.

It

is sometimes suggested that tournament fights at the barriers forbade

strokes below the waist, yet the real reason for employing barriers

in the first place was to prevent grappling and wrestling between

combatants and to help to limit the lethality of contests.

Plus, for every reference to tourneys which excluded leg strikes there

can be found one that did not. In some tourneys in fact,

there were even special penalties against a knight who fell to his

knees or had to steady himself with a hand on the ground. It

is sometimes suggested that tournament fights at the barriers forbade

strokes below the waist, yet the real reason for employing barriers

in the first place was to prevent grappling and wrestling between

combatants and to help to limit the lethality of contests.

Plus, for every reference to tourneys which excluded leg strikes there

can be found one that did not. In some tourneys in fact,

there were even special penalties against a knight who fell to his

knees or had to steady himself with a hand on the ground.

In

the 14th century tale, Le Petit Jehan De Saintré, Antoine De

Le Salle writing of a knightly duel states: "…to

combat against them on foot with pole-axes and small-swords only,

until the one party or the other should be borne to earth or disarmed

of their weapons." It was well understood that a combatant on

the ground was no challenge and realistically had no chance.

As Fiore Dei Liberi symbolized in his fighting manual of 1410, the

legs are like the strength of an elephant, a fortress, and "never

[will] I kneel down or I [will] lose my balance"—a master

of arms himself offering unequivocal advice. In

the 14th century tale, Le Petit Jehan De Saintré, Antoine De

Le Salle writing of a knightly duel states: "…to

combat against them on foot with pole-axes and small-swords only,

until the one party or the other should be borne to earth or disarmed

of their weapons." It was well understood that a combatant on

the ground was no challenge and realistically had no chance.

As Fiore Dei Liberi symbolized in his fighting manual of 1410, the

legs are like the strength of an elephant, a fortress, and "never

[will] I kneel down or I [will] lose my balance"—a master

of arms himself offering unequivocal advice.

In

the fictional account of a 14th century knight, Le petit

Jehan de Saintré, we are told how in a challenge Saintre stood

firm and "…with the great force of his thrusting, Sir Nicolo

fell to the ground on his hands and knees. At that Saintre lifted

up his foot, for to have dealt him a buffet in the side and borne

him altogether to the ground; but for his honor’s sake he forebare."

Here we have a description of a judicial duel in which once down the

combatant is beaten, yet if desired may still continue to be attacked.

Froissart relates a judicial duel from 1386 between the Chevaliers

de Carrouges and Jacques le Gris. Witnessed by the king himself, the

ailing de Carrouges on the verge of losing was able to run his sword

through the prostrate Gris. In

the fictional account of a 14th century knight, Le petit

Jehan de Saintré, we are told how in a challenge Saintre stood

firm and "…with the great force of his thrusting, Sir Nicolo

fell to the ground on his hands and knees. At that Saintre lifted

up his foot, for to have dealt him a buffet in the side and borne

him altogether to the ground; but for his honor’s sake he forebare."

Here we have a description of a judicial duel in which once down the

combatant is beaten, yet if desired may still continue to be attacked.

Froissart relates a judicial duel from 1386 between the Chevaliers

de Carrouges and Jacques le Gris. Witnessed by the king himself, the

ailing de Carrouges on the verge of losing was able to run his sword

through the prostrate Gris.

At the battle of Crècy in 1346, the sixteen-year-old Prince

Edward, outnumbered in fierce hand-to-hand fighting became the target

of many direct attacks so that on one occasion he was briefly "compelled

to fight on his knees" (Geoffrey le Baker, Chronicon,

p. 84). But falling down while surrounded and protected

by retainers hardly qualifies as effectively fighting from a kneeling

position after being seriously wounded in a leg.

In

a duel with bastard-swords in the early 1500s, one Fendilles delivered

a thrust to the thigh of the Barron DeGuerres that laid it completely

open. Yet, despite such a terrible leg wound the Baron was still able

to charge and wrestle his opponent before dying from blood loss. The

mid 15th century English text on great-sword, MS 39564,

also instructs leg blows, stating in its 22nd entry to

"lyghtly pley a rabett at hys legge lowe by ye grownde",

while in its 23rd entry it speaks of "smytng a full

spryng at hys legge". Examining Medieval sources then, it appears only severely

hacking or copping into a leg with a sturdy cutting blade would effect

a combatant, and when it did, he would drop to the ground and no longer

be capable of fighting. With lighter, narrower Renaissance sword duels,

as well, there is no evidence whatsoever of either thrust or blow

disabling an opponent and a significant amount to the contrary. In

a duel with bastard-swords in the early 1500s, one Fendilles delivered

a thrust to the thigh of the Barron DeGuerres that laid it completely

open. Yet, despite such a terrible leg wound the Baron was still able

to charge and wrestle his opponent before dying from blood loss. The

mid 15th century English text on great-sword, MS 39564,

also instructs leg blows, stating in its 22nd entry to

"lyghtly pley a rabett at hys legge lowe by ye grownde",

while in its 23rd entry it speaks of "smytng a full

spryng at hys legge". Examining Medieval sources then, it appears only severely

hacking or copping into a leg with a sturdy cutting blade would effect

a combatant, and when it did, he would drop to the ground and no longer

be capable of fighting. With lighter, narrower Renaissance sword duels,

as well, there is no evidence whatsoever of either thrust or blow

disabling an opponent and a significant amount to the contrary.

With rapiers, the results of leg wounds change but are just as interesting.

The period chronicler Brantôme for example chronicles a sword and

dagger duel from the mid 1500s wherein the combatants armored in long

"sleeves of mail" made attacks mainly at the leg .One soon

inflicted a serious and gaping wound, from which the blood flowed

freely. The wounded man still continued on and made a fierce thrust

and two rapid cuts in succession at the other, but with no success.

He did not sit or kneel. With rapiers, the results of leg wounds change but are just as interesting.

The period chronicler Brantôme for example chronicles a sword and

dagger duel from the mid 1500s wherein the combatants armored in long

"sleeves of mail" made attacks mainly at the leg .One soon

inflicted a serious and gaping wound, from which the blood flowed

freely. The wounded man still continued on and made a fierce thrust

and two rapid cuts in succession at the other, but with no success.

He did not sit or kneel.

In

a duel in the early 1500s between Captain Saincte-Croix and a Spanish

Cavalier, Signor Azevedo, Saincte-Croix received such a wound on the

upper part of his thigh as laid bare the bone and caused such a flow

of blood that in trying to advance and revenge the blow he fell. On

seeing that, Azevedo tried to get Saincte-Croix to surrender, but

he just sat grasping his sword. Azevedo then said, ‘Get up; I

can’t strike you like that.’ Saincte-Croix got up and walked

two steps before falling again. Here we have no standing, no sitting

down, and no fighting. Acting as a second in a duel in the early 1500s,

Girolamo Muzio did once refuse to permit the use of armor that did

not allow kneeling, but this was because it did not allow the parties

to properly pray. In

a duel in the early 1500s between Captain Saincte-Croix and a Spanish

Cavalier, Signor Azevedo, Saincte-Croix received such a wound on the

upper part of his thigh as laid bare the bone and caused such a flow

of blood that in trying to advance and revenge the blow he fell. On

seeing that, Azevedo tried to get Saincte-Croix to surrender, but

he just sat grasping his sword. Azevedo then said, ‘Get up; I

can’t strike you like that.’ Saincte-Croix got up and walked

two steps before falling again. Here we have no standing, no sitting

down, and no fighting. Acting as a second in a duel in the early 1500s,

Girolamo Muzio did once refuse to permit the use of armor that did

not allow kneeling, but this was because it did not allow the parties

to properly pray.

Brantôme

also informs us of a duel between Gouard and Chastaigneraye (of later

Jarnac fame) where the latter would not kill his man while he lay

fallen but waited for him to get up again. In the oft mentioned 1547

judicial duel between the nobles Chastaignerai and Jarnac, Jarnac

delivered a slicing cut behind one of his Chastaignerai’s legs

(to the ham or knee, sources are not specific). However, the accounts

are specific that from this simple cut by a light blade (the

infamous "Coup de Jarnac"), Chastaignerai instantly fell

down prone to the ground. Knowing the fight over from this result

Jarnac backed off and Chastaignerai was able to recover himself. But

from the injury he could barely stand. Resuming reluctantly, Jarnac

then made the same attack on the other leg of his stubborn but

valiant opponent and from this second atatck Chastaignerai could not

stand at all. From the first wound Jarnac well knew the fight was

over and his opponent could not continue. Chastaignerai certainly

did not sit up or continue combat from his rump or threaten to bite

Jarnac’s legs off. Brantôme

also informs us of a duel between Gouard and Chastaigneraye (of later

Jarnac fame) where the latter would not kill his man while he lay

fallen but waited for him to get up again. In the oft mentioned 1547

judicial duel between the nobles Chastaignerai and Jarnac, Jarnac

delivered a slicing cut behind one of his Chastaignerai’s legs

(to the ham or knee, sources are not specific). However, the accounts

are specific that from this simple cut by a light blade (the

infamous "Coup de Jarnac"), Chastaignerai instantly fell

down prone to the ground. Knowing the fight over from this result

Jarnac backed off and Chastaignerai was able to recover himself. But

from the injury he could barely stand. Resuming reluctantly, Jarnac

then made the same attack on the other leg of his stubborn but

valiant opponent and from this second atatck Chastaignerai could not

stand at all. From the first wound Jarnac well knew the fight was

over and his opponent could not continue. Chastaignerai certainly

did not sit up or continue combat from his rump or threaten to bite

Jarnac’s legs off.

In

the mid 1500s a combat took place between Albert de Luignes and Captain

Panier, fought before the King in the woods of Vincennes, wherein

Panier inflicted a severe wound on the head of his opponent, who fell

upon his knee; his seconds ran to the rescue; but Luignes, recovering

himself, gave him a mortal wound thrust through the body. There was

no attempt to fight sitting down. In the late 1500s a duel between

Signor Amadeo and one Crequi fought on an island in the Rhone. Crequi

brought Amadeo to the ground and without more ado killed him –so

that Amadeo’s relatives later complained of the recumbent manner

in which their fellow perished. In

the mid 1500s a combat took place between Albert de Luignes and Captain

Panier, fought before the King in the woods of Vincennes, wherein

Panier inflicted a severe wound on the head of his opponent, who fell

upon his knee; his seconds ran to the rescue; but Luignes, recovering

himself, gave him a mortal wound thrust through the body. There was

no attempt to fight sitting down. In the late 1500s a duel between

Signor Amadeo and one Crequi fought on an island in the Rhone. Crequi

brought Amadeo to the ground and without more ado killed him –so

that Amadeo’s relatives later complained of the recumbent manner

in which their fellow perished.

Brantôme

tells us that in the 1570’s the fugitive Baron De Vitaux with

two compatriots ambushed one Millaud in front of his own house as

he emerged (this was but one of three such surprise attacks against

other gentleman made by the Baron over the years). Before he was killed

in the assault, Millaud wounded one of his attackers in the leg with

his rapier and "caused him great loss of blood but did not prevent

his escape". Brantôme

tells us that in the 1570’s the fugitive Baron De Vitaux with

two compatriots ambushed one Millaud in front of his own house as

he emerged (this was but one of three such surprise attacks against

other gentleman made by the Baron over the years). Before he was killed

in the assault, Millaud wounded one of his attackers in the leg with

his rapier and "caused him great loss of blood but did not prevent

his escape".

In 1567, the seventeen-year-old Edward de Vere, the future 17th Earl

of Oxford, while practicing fencing with Edward Baynam, a tailor,

in the backyard of his guardian's mansion in the Strand, accidentally

wounded an unarmed undercook named Thomas Brincknell with a rapier

thrust to the thigh. Brincknell died the next day. A crooked jury

later determined Brincknell who was drunk had caused his own death

and had committed suicide by wilfully hurling himself on de Vere's

rapier. (Interestingly, this is also the earliest reference to the

rapier in England, and apparently being taught to a young noble by

a common tailor).

The

Master Giacomo Di Grassi in the 1570’s advised several times

in various ways that the "enimies legge must be cutt with the

edge" but never once implied doing so would cause the opponent

to drop down or keel over. Nor did Di Grassi advise any thrusting

to the legs. Vincentio Saviolo in His

Practice in Two Books, of 1594 also advises that with a wider

sharper rapier "the Scholler maye likewise give a mandritta

at the legges" and suggests "strike the said riversa or

crosse blowe at his legs". Yet,

George Silver writing on Illusions for the maintenance of imperfect

weapons & false fights in Chapter 10 of his Paradoxes,

declared that in regard to swords: "When blows were used, men

were so simple in their fight, that they thought him a coward, that

would make a thrust or a blow beneath the girdle." The

Master Giacomo Di Grassi in the 1570’s advised several times

in various ways that the "enimies legge must be cutt with the

edge" but never once implied doing so would cause the opponent

to drop down or keel over. Nor did Di Grassi advise any thrusting

to the legs. Vincentio Saviolo in His

Practice in Two Books, of 1594 also advises that with a wider

sharper rapier "the Scholler maye likewise give a mandritta

at the legges" and suggests "strike the said riversa or

crosse blowe at his legs". Yet,

George Silver writing on Illusions for the maintenance of imperfect

weapons & false fights in Chapter 10 of his Paradoxes,

declared that in regard to swords: "When blows were used, men

were so simple in their fight, that they thought him a coward, that

would make a thrust or a blow beneath the girdle."

In Note

8 of this statement, he elaborates that when "weapons were short,

as in times past": "…to strike beneath the waist, or

at the legs, is a great disadvantage, because the course of the blow

to the legs is too far, & thereby the head, face & body is

discovered. And that was the cause in old time(s), that they did not

thrust or strike at the legs, & not for lack of skill, as is these

days we imagine." Given the evidence from tournaments and judicial

duels wherein victories were secured by thigh and leg blows, Silver

may here be referring perhaps to knightly tournaments of the early

1500s, or to earlier public Prize Playings, or even the common rough-and-tumble

street brawls with sword and buckler. In Note

8 of this statement, he elaborates that when "weapons were short,

as in times past": "…to strike beneath the waist, or

at the legs, is a great disadvantage, because the course of the blow

to the legs is too far, & thereby the head, face & body is

discovered. And that was the cause in old time(s), that they did not

thrust or strike at the legs, & not for lack of skill, as is these

days we imagine." Given the evidence from tournaments and judicial

duels wherein victories were secured by thigh and leg blows, Silver

may here be referring perhaps to knightly tournaments of the early

1500s, or to earlier public Prize Playings, or even the common rough-and-tumble

street brawls with sword and buckler.

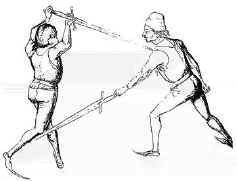

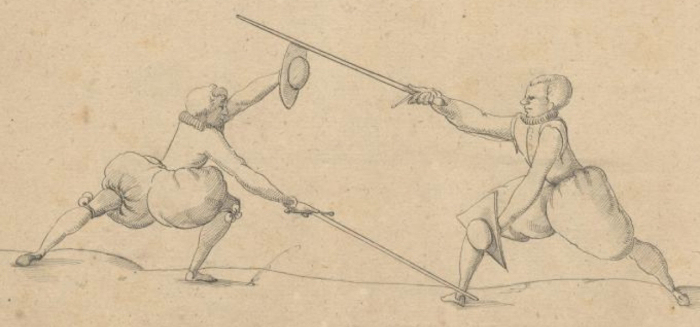

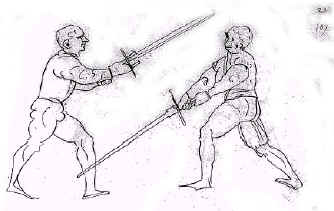

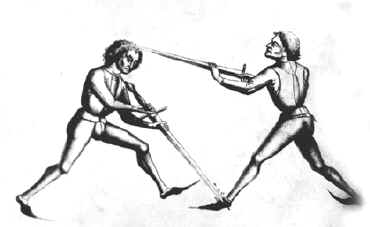

Girolamo

Cavalcabo in his text of c. 1580 is one of the very few to illustrate

any solid thrust to the leg, in this case a string straight attack

into the shin with his long, slender, tapering blade of flat-diamond

cross-section (...that's gotta hurt). Cavalcabo's action is actually

a counter attack made on the pass with a left-hand parry of the opponent's

thrust. Girolamo

Cavalcabo in his text of c. 1580 is one of the very few to illustrate

any solid thrust to the leg, in this case a string straight attack

into the shin with his long, slender, tapering blade of flat-diamond

cross-section (...that's gotta hurt). Cavalcabo's action is actually

a counter attack made on the pass with a left-hand parry of the opponent's

thrust.

The French Master Sainct Didier in 1573 advised several times

slashes to the calf of the opponent --but not the front of the leg

or the thigh. The reason being obviously that a good solid hit to

the lower leg muscle is of greater effect than a whack with a slender

blade across the hard shin bone or the thick upper leg. In his 1617

treatise on sword, rapier, and staff, Joseph Swetnam advised it was

safest to attack the adversary’s nearest target "whether

it be his dagger hand, his knee, or his leg". As he often

did, Swetnam was writing ambiguously in reference to either sword

or rapier.

|

|

|

|

|

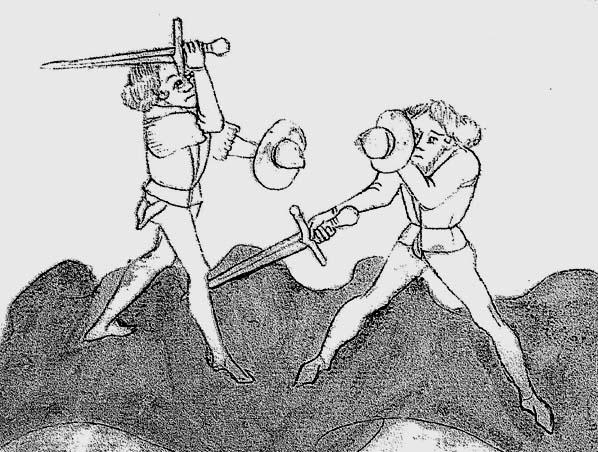

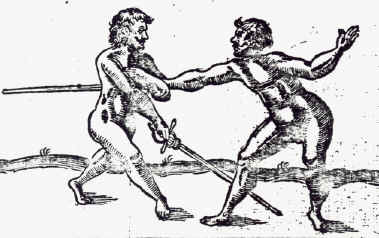

From

a Medieval tale, Signeot versus the giant from a 15th century

manuscript.

|

Writing in 1631 of the old sword and buckler brawls,

Stowe stated, "Yet seldome any man hurt, for thrusting was not

then in use: neither would one of twentie strike beneath the waste,

by reason they helde it cowardly and beastly." What is of significance

here, is the obvious understanding that when one does strike below

the waist, serious and disabling injury results. Thus it would be

understandable such actions might have be excluded from practice playing

just as thrust to the face would have, but as we’ll see later

this was not the case.

Silver, who is known for criticizing the rapiers, also complained

of the inferiority of thrusting over cutting by saying: "And

again, the thrust being made through the hand, arm, or leg, or in

many places of the body and face, are not deadly, neither are they

maims, or loss of limbs or life, neither is he much hindered for the

time in his fight, as long as the blood is hot." Silver also

argued, "I have known a Gentleman hurt in Rapier fight, in nine

or ten places through the bodie, arms, and legges, and yet hath continued

in his fight, & afterward has slaine the other". Again, no

sitting down here. Silver’s weapon was a sturdy cut-and-thrust

blade, no slender rapier and he added "…A blow upon the

hand, arme, or legge is maime incurable; but a thrust in the hand,

arme, or legge is to be recovered." In his "Circle Number

8" of his 1630 fencing treatise, Thibault mentions side stepping

to deliver a diagonal blow to the meat of the thick part of the opponent’s

thigh. But Thibault immediately adds a continuation by thrust to follow

up, and never even suggests the thigh blow was any thing than a distracting

attack to gain advantage. He, as with every other Renaissance master,

never mentions anything about a fencer sitting or kneeling. Silver, who is known for criticizing the rapiers, also complained

of the inferiority of thrusting over cutting by saying: "And

again, the thrust being made through the hand, arm, or leg, or in

many places of the body and face, are not deadly, neither are they

maims, or loss of limbs or life, neither is he much hindered for the

time in his fight, as long as the blood is hot." Silver also

argued, "I have known a Gentleman hurt in Rapier fight, in nine

or ten places through the bodie, arms, and legges, and yet hath continued

in his fight, & afterward has slaine the other". Again, no

sitting down here. Silver’s weapon was a sturdy cut-and-thrust

blade, no slender rapier and he added "…A blow upon the

hand, arme, or legge is maime incurable; but a thrust in the hand,

arme, or legge is to be recovered." In his "Circle Number

8" of his 1630 fencing treatise, Thibault mentions side stepping

to deliver a diagonal blow to the meat of the thick part of the opponent’s

thigh. But Thibault immediately adds a continuation by thrust to follow

up, and never even suggests the thigh blow was any thing than a distracting

attack to gain advantage. He, as with every other Renaissance master,

never mentions anything about a fencer sitting or kneeling.

Occasionally

today in their rapier fencing enthusiasts will assume that a push

or draw cut to the inside of the thigh would be an immediate "disabling"

action because of the large arteries in those areas. The nature of

the blades, the advice of the historical masters, and modern cutting

experiments on raw meat contradict this belief. There are no accounts

of such actions where the blade is placed against the target and forcefully

drawn or pulled across ever resulting in kills during any rapier

duel or even combats with wider, sharper Medieval cutting swords.

Nor do the period manuals (such as Thibualt's) suggest such a move

would be either a killing or disabling action. Occasionally

today in their rapier fencing enthusiasts will assume that a push

or draw cut to the inside of the thigh would be an immediate "disabling"

action because of the large arteries in those areas. The nature of

the blades, the advice of the historical masters, and modern cutting

experiments on raw meat contradict this belief. There are no accounts

of such actions where the blade is placed against the target and forcefully

drawn or pulled across ever resulting in kills during any rapier

duel or even combats with wider, sharper Medieval cutting swords.

Nor do the period manuals (such as Thibualt's) suggest such a move

would be either a killing or disabling action.

The

clothing worn at the time of the rapier is also a factor, as thick

wool or leather lined garments common in the period cannot be sliced

through by a narrow, light blade. Consider the statement by Sir James

Turner in his 1683 Pallas Armata –Military Essayes of the

Ancient Grecian, Roman, and Modern Art of War: "It were to

be wish’d that if Horsemen be obliged by their capitulation to

furnish themselves with swords, that their Officers would see them

provided of better than ordinarily most of them carry, which are such

as may be well enough resisted by either a good Felt, or a Buff-coat."

(London, Richard Chiswell, 1683, p. 171). Sir Turner makes this comment

referring to cavalry blades, so consider how much more it holds true

for either blows or "draw cuts" by the slender blade of

the rapier. As George Silver in his Paradoxes so firmly said, "A

full blow upon the head, face, arm, leg, or legs, is death, or the

party so wounded in the mercy of him that shall so wound him. For

what man shall be able long in fight to stand up, either to revenge,

or defend himself, having the veins, muscles, sinews of his hand,

arm, or leg clean cut asunder?" Examining Renaissance accounts

then, neither piercing nor slashing nor slicing upon a leg with a

rapier would have much effect upon a fighter. The

clothing worn at the time of the rapier is also a factor, as thick

wool or leather lined garments common in the period cannot be sliced

through by a narrow, light blade. Consider the statement by Sir James

Turner in his 1683 Pallas Armata –Military Essayes of the

Ancient Grecian, Roman, and Modern Art of War: "It were to

be wish’d that if Horsemen be obliged by their capitulation to

furnish themselves with swords, that their Officers would see them

provided of better than ordinarily most of them carry, which are such

as may be well enough resisted by either a good Felt, or a Buff-coat."

(London, Richard Chiswell, 1683, p. 171). Sir Turner makes this comment

referring to cavalry blades, so consider how much more it holds true

for either blows or "draw cuts" by the slender blade of

the rapier. As George Silver in his Paradoxes so firmly said, "A

full blow upon the head, face, arm, leg, or legs, is death, or the

party so wounded in the mercy of him that shall so wound him. For

what man shall be able long in fight to stand up, either to revenge,

or defend himself, having the veins, muscles, sinews of his hand,

arm, or leg clean cut asunder?" Examining Renaissance accounts

then, neither piercing nor slashing nor slicing upon a leg with a

rapier would have much effect upon a fighter.

Writing

in 1662 of English "Gladiatorial" prize fighters he had

witnessed, Samuel Pepys in his famed diary described "…one

Westwicke, who was soundly cut several times both in the head and

legs, that he was all over blood; and other deadly blows they did

give and take in very good earnest, til Westwicke was in a sad pickle."

John Godfrey, commenting on the skill of the 18th century prize-fighter,

William Gill, foremost pupil of the renowned prize-fighter, James

Fig, wrote: "I never beheld any Body better for the Leg than

Gill. …he oftener hit the Leg than any one; and…his Cuts

were remarkably more severe and deep. I never was an Eye-Witness to

such a Cut in the Leg, as he gave one Butler, an Irishman, a bold

resolute Man, but an aukward Swords-Man. His Leg was laid quite open,

his Calf falling down to his Ancle". But Westwicke neither fell

nor fought from the ground. Even in a small-sword duel of 1712, the

Duke of Hamilton received a seven inch wound on the right side of

the leg, another in the right arm, a third in the upper part of the

right breast, and fourth on the outside of the left leg…yet was

survived victorious. Writing

in 1662 of English "Gladiatorial" prize fighters he had

witnessed, Samuel Pepys in his famed diary described "…one

Westwicke, who was soundly cut several times both in the head and

legs, that he was all over blood; and other deadly blows they did

give and take in very good earnest, til Westwicke was in a sad pickle."

John Godfrey, commenting on the skill of the 18th century prize-fighter,

William Gill, foremost pupil of the renowned prize-fighter, James

Fig, wrote: "I never beheld any Body better for the Leg than

Gill. …he oftener hit the Leg than any one; and…his Cuts

were remarkably more severe and deep. I never was an Eye-Witness to

such a Cut in the Leg, as he gave one Butler, an Irishman, a bold

resolute Man, but an aukward Swords-Man. His Leg was laid quite open,

his Calf falling down to his Ancle". But Westwicke neither fell

nor fought from the ground. Even in a small-sword duel of 1712, the

Duke of Hamilton received a seven inch wound on the right side of

the leg, another in the right arm, a third in the upper part of the

right breast, and fourth on the outside of the left leg…yet was

survived victorious.

There

is no question the feet and legs were prime targets in all forms of

Medieval combat. In its finale, the 15th century "Poem of the

Pell" instructs "Hew of his honde, his legge, his theys,

his armys". In his text on swordplay from the 1480s, master Fillipo

Vadi even offered advice on what to do "if the head or left foot

are under attack, because they are closer to the enemy than the right".

From, Le Jeu de la Hache, a 15th century Burgundian treatise

on the technique of chivalric poleax combat, we read the advice: "You

can jab at his face with the queue [lower end of the haft]

of your axe, or at his". Still further it admonishes, "If

he gives you a jab to the foot with his queue, you must lift

your foot, while presenting your queue against his, which has

no protection" and "you must deliver these jabs frequently,

sometimes at the foot and sometimes at the hand or face". Achilles

Marozzo in part 4 of his 1536, Opera Nova, comments several

times on leg and foot strikes saying: "and if your enemy would

attack your head or leg, you should move your left foot sideways towards

the right side of your foe, and strike with a roverso at his head"

and if "your enemy would attack your head or legs …make

a long step…and at the same time put your sword and buckler close

together to parry the said strike, and strike his legs". There

is no question the feet and legs were prime targets in all forms of

Medieval combat. In its finale, the 15th century "Poem of the

Pell" instructs "Hew of his honde, his legge, his theys,

his armys". In his text on swordplay from the 1480s, master Fillipo

Vadi even offered advice on what to do "if the head or left foot

are under attack, because they are closer to the enemy than the right".

From, Le Jeu de la Hache, a 15th century Burgundian treatise

on the technique of chivalric poleax combat, we read the advice: "You

can jab at his face with the queue [lower end of the haft]

of your axe, or at his". Still further it admonishes, "If

he gives you a jab to the foot with his queue, you must lift

your foot, while presenting your queue against his, which has

no protection" and "you must deliver these jabs frequently,

sometimes at the foot and sometimes at the hand or face". Achilles

Marozzo in part 4 of his 1536, Opera Nova, comments several

times on leg and foot strikes saying: "and if your enemy would

attack your head or leg, you should move your left foot sideways towards

the right side of your foe, and strike with a roverso at his head"

and if "your enemy would attack your head or legs …make

a long step…and at the same time put your sword and buckler close

together to parry the said strike, and strike his legs".

It is interesting to note that while attacks to the lower legs in

sword combat are evident in earlier combats, they begin to disappear

from swordplay by the 19th century. Some 18th & 19th century fencing

schools continued to value it to one degree or another, but various

fencing masters of the 1800’s advised against cuts to the lower

leg and upper thigh or even below the waist entirely (as is now customary

in sport saber fencing). Why the change? Such strikes were declared

by many 18th & 19th century fencing masters as too easy to avoid

by withdrawing the exposed leg and countering with cuts to the head,

arm or hand. It is interesting to note that while attacks to the lower legs in

sword combat are evident in earlier combats, they begin to disappear

from swordplay by the 19th century. Some 18th & 19th century fencing

schools continued to value it to one degree or another, but various

fencing masters of the 1800’s advised against cuts to the lower

leg and upper thigh or even below the waist entirely (as is now customary

in sport saber fencing). Why the change? Such strikes were declared

by many 18th & 19th century fencing masters as too easy to avoid

by withdrawing the exposed leg and countering with cuts to the head,

arm or hand.

They expressed exactly this standard philosophy that an able swordsman

never exposed his head and shoulders by cutting so low. But ironically,

Sir Richard Burton (who subscribed to this very view) admitted in

his 1876, A New System of Sword Exercise for Infantry, that

"In our Single-stick practice the first thought seems to be to

attack the advanced leg –which may be well enough for Single-stick"

(in his mid 19th century Sentiments of the Sword, Burton had

also noted how the "Oriental [e.g. Indian or Arab] affects only

two cuts, the shoulder blow and the "kulam," or leg slash).

Defending

against leg strikes by moving the target and hitting back was certainly

nothing new in later times, it was an element in all earlier fighting

and is even detectable in Fiore’s manual as well as Sigmund Ringeck’s

and Marozzo’s. Among the different saber-schools of the

19th century, polite manners and gentlemanly consensus, not necessarily

martial effectiveness, could frequently determined acceptable target

areas for practice or duel (actually, leg targets were included in

some schools of sport sabre fencing up until the early 20th century).

Yet obviously, as swords lost more and more of their military value

and cutting actions went from full cleaving blows to light slashes

from the wrist and elbow, the nature of swordplay changed (not to

mention that shorter, lighter blades are employed differently than

dedicated cutting swords used with shield, buckler, or dagger, and

are different still from longer double-hand weapons used against armors). Defending

against leg strikes by moving the target and hitting back was certainly

nothing new in later times, it was an element in all earlier fighting

and is even detectable in Fiore’s manual as well as Sigmund Ringeck’s

and Marozzo’s. Among the different saber-schools of the

19th century, polite manners and gentlemanly consensus, not necessarily

martial effectiveness, could frequently determined acceptable target

areas for practice or duel (actually, leg targets were included in

some schools of sport sabre fencing up until the early 20th century).

Yet obviously, as swords lost more and more of their military value

and cutting actions went from full cleaving blows to light slashes

from the wrist and elbow, the nature of swordplay changed (not to

mention that shorter, lighter blades are employed differently than

dedicated cutting swords used with shield, buckler, or dagger, and

are different still from longer double-hand weapons used against armors).

Curiously,

the master Fiore Dei Liberi in his treatise of 1410 reasonably advised:

"When someone strikes to your leg, step slip with your forefoot.

You retreat backwards and strike a downward cut in his head..."

This same advice was to be found in many later works. However, he

then asserted (despite the iconographic and practical evidence to

the contrary from the era) that low leg hits were specifically impractical

with a longsword: "With a two-handed sword you can not strike

well from the knee downwards, because it is very dangerous for the

one who strikes, because the one who attacks the leg remains all uncovered.

Unless one has fallen on the ground, then he can injure the leg well,

otherwise you can not, being sword against sword." His

logic was sound, and yet the longer the weapon the easier lower leg

hits are. Curiously,

the master Fiore Dei Liberi in his treatise of 1410 reasonably advised:

"When someone strikes to your leg, step slip with your forefoot.

You retreat backwards and strike a downward cut in his head..."

This same advice was to be found in many later works. However, he

then asserted (despite the iconographic and practical evidence to

the contrary from the era) that low leg hits were specifically impractical

with a longsword: "With a two-handed sword you can not strike

well from the knee downwards, because it is very dangerous for the

one who strikes, because the one who attacks the leg remains all uncovered.

Unless one has fallen on the ground, then he can injure the leg well,

otherwise you can not, being sword against sword." His

logic was sound, and yet the longer the weapon the easier lower leg

hits are.

Leg wounds thus, are either very serious matters or not at all. There

appears little in between. Even in later combats this was still true.

In an 1846 official duel at Munster, two young officers fought with

sabres in a roped off area. One received two slight cuts on the arm

but soon gave his opponent "a cut in the thigh which toppled

him over upon the ground, and made it impossible for him to continue

the combat." In an 1858 epee’ duel in France, the Marquis

de Galiffet and De Lauriston fought for 30 minutes. The latter was

wounded in the hand and the former pierced in the thigh so that the

physician concluded he could not continue. Leg wounds thus, are either very serious matters or not at all. There

appears little in between. Even in later combats this was still true.

In an 1846 official duel at Munster, two young officers fought with

sabres in a roped off area. One received two slight cuts on the arm

but soon gave his opponent "a cut in the thigh which toppled

him over upon the ground, and made it impossible for him to continue

the combat." In an 1858 epee’ duel in France, the Marquis

de Galiffet and De Lauriston fought for 30 minutes. The latter was

wounded in the hand and the former pierced in the thigh so that the

physician concluded he could not continue.

So what conclusions can we draw then? Without a doubt, the factors

of physiology and psychology are important in the effects of any wounds.

Yet even today law enforcement and military specialists will comment

that firearm wounds to the legs either break and shatter bone –thus

preventing standing –or else do not disable the victim from standing

and even running. From Viking Sagas in the 9th century to British

Army reports in the 19th, there are accounts of blows by cutting blades

removing legs above the knee or both legs below the knee… but

never once of any combatants sitting or kneeling to fight while wounded

in the hips or legs. Thus, when wounded by a leg blow, depending

on the severity of the attack, a fighter either immediately fell down

if it was grievous or else they managed to continue on without toppling

over. Leg wounds even seem to make up a larger portion of injuries

in sword combat than any other except head wounds. This is no

surprise since arms and torsos are often protected by shields and

are more easily armored (besides, feinting high and striking low is

a fundamental attack). So what conclusions can we draw then? Without a doubt, the factors

of physiology and psychology are important in the effects of any wounds.

Yet even today law enforcement and military specialists will comment

that firearm wounds to the legs either break and shatter bone –thus

preventing standing –or else do not disable the victim from standing

and even running. From Viking Sagas in the 9th century to British

Army reports in the 19th, there are accounts of blows by cutting blades

removing legs above the knee or both legs below the knee… but

never once of any combatants sitting or kneeling to fight while wounded

in the hips or legs. Thus, when wounded by a leg blow, depending

on the severity of the attack, a fighter either immediately fell down

if it was grievous or else they managed to continue on without toppling

over. Leg wounds even seem to make up a larger portion of injuries

in sword combat than any other except head wounds. This is no

surprise since arms and torsos are often protected by shields and

are more easily armored (besides, feinting high and striking low is

a fundamental attack).

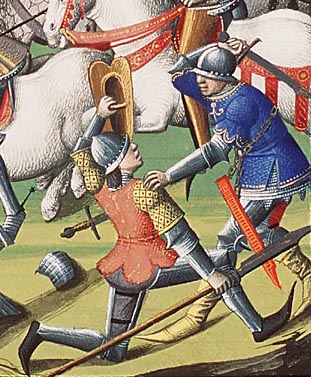

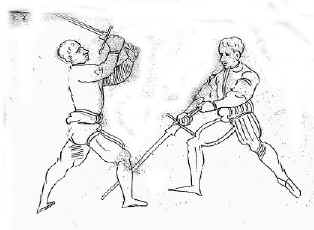

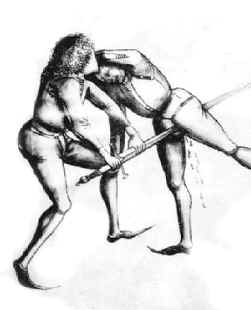

From an anonymous 15th century German manuscript illustrating a chivalric

romance a villainous knight his defeated only after he is chopped

to pieces limb by limb in a Pythonesque scene. From the work, one

knight in a judicial duel is shown knocked from his horse and severely

wounded struggling to rise from his knees as his opponent prepares

to finish him.

As can be seen in the above cases of recorded historical combats,

there is no sitting or kneeling whilst fighting…and no attacking

of opponents while sitting. There is nothing within any account

of Medieval or Renaissance combat to support doing so as a reasonable

simulation of weapon injury. Nor is there any chivalric

or code duello evidence in favor of the practice, whether in battle,

tourney, judicial combat, affray, or private duel of honor. There

simply is zero historical, physiological, forensic, or martial legitimacy

to the assumptions supporting the practice of continuing free-play

or mock-fighting from a kneeling or sitting position. Indeed,

there is in fact no evidence whatsoever for such practices within

study of a subject as exciting and rich as Medieval & Renaissance

combat. Is it any surprise that not one of the more than 100 surviving

historical fencing texts (both printed books and un-published manuscript)

from the 13th to the 17th centuries offer us a single "technique

for fighting from the ground"? Perhaps these facts will

eventually give pause to historical groups wherein the lamentable

habit of conducting fencing while sitting or kneeling is conducted…a

habit whose fundamental premise is without historical foundation or

martial validity. As can be seen in the above cases of recorded historical combats,

there is no sitting or kneeling whilst fighting…and no attacking

of opponents while sitting. There is nothing within any account

of Medieval or Renaissance combat to support doing so as a reasonable

simulation of weapon injury. Nor is there any chivalric

or code duello evidence in favor of the practice, whether in battle,

tourney, judicial combat, affray, or private duel of honor. There

simply is zero historical, physiological, forensic, or martial legitimacy

to the assumptions supporting the practice of continuing free-play

or mock-fighting from a kneeling or sitting position. Indeed,

there is in fact no evidence whatsoever for such practices within

study of a subject as exciting and rich as Medieval & Renaissance

combat. Is it any surprise that not one of the more than 100 surviving

historical fencing texts (both printed books and un-published manuscript)

from the 13th to the 17th centuries offer us a single "technique

for fighting from the ground"? Perhaps these facts will

eventually give pause to historical groups wherein the lamentable

habit of conducting fencing while sitting or kneeling is conducted…a

habit whose fundamental premise is without historical foundation or

martial validity.

"Beholde a fencer, who making at his

enimies head,

striketh him on the legge"

- Guazzo

Note: This material was compiled from

the forthcoming book on Histrocial Fencing by the author, source

references were removed from the online version. Copyright (c) 2000

See also: Kneeling

Down in Weapon Sparring Rules and Importance of the Full Leg Target in Weapon Sparring

Back to the Essays Page |