|

Ten

Reasons Why Longsword Fencing Differs

...So

Much from Modern Fencing

By John Clements

ARMA Director

The distinctions between

the wielding of a long two-edged doubled-handed sword compared to that

employed with the shorter, far lighter, single-hand sporting tools of

modern fencing---foil, epee, sabre---are largely self-evident. However,

as a historical swordplay expert the question is occasionally asked of

me how exactly they differ. The answer I typically offer is that the difference

is quite simple, yet also both profound and subtle in consequence. I also

find the question itself an opportunity to address several significant

issues within historical fencing studies and the modern practice of Renaissance

martial arts.

Part of the reason in the first place for

the question of how the two styles differ is, perhaps, because so much

perspective has been lost on the subject of swords and swordsmanship.

People are unable to place either historical or modern fencing in their

proper context. The popular conception of fencing today comes from exposure

to the classical styles of the modern sport and the pervasive influence

they have had for decades as the basis of most all swordplay in popular

entertainment.

This

is a testament to how little is presently understood about authentic Renaissance

swordplay and how far there still is to go in reviving the craft. While

a comparison can be made between most any types of historical swords,

this specific question likely comes up because most people are more familiar

with a conception of historical European swordplay through the collegiate/Olympic

version of fencing game. In light of the ignorance many modern fencers

hold about Renaissance era swords and sword combat, honest attempts to

offer contrast and comparison can frequently take the form of criticism.

The effort here a will be in addressing the question as an academic exercise. This

is a testament to how little is presently understood about authentic Renaissance

swordplay and how far there still is to go in reviving the craft. While

a comparison can be made between most any types of historical swords,

this specific question likely comes up because most people are more familiar

with a conception of historical European swordplay through the collegiate/Olympic

version of fencing game. In light of the ignorance many modern fencers

hold about Renaissance era swords and sword combat, honest attempts to

offer contrast and comparison can frequently take the form of criticism.

The effort here a will be in addressing the question as an academic exercise.

Despite

the universal elements of timing, range, and perception (of both leverage

and action) that underlie all styles of fencing, there are at least ten

major reasons why the longsword differs so much from modern fencing’s

foil, épée, and sabre. The disparity revealed in this contrast underscores

their considerable dissimilarity. Spotlighting these differences I believe

can go a long way toward helping understand the place of Renaissance martial

arts study today. Despite

the universal elements of timing, range, and perception (of both leverage

and action) that underlie all styles of fencing, there are at least ten

major reasons why the longsword differs so much from modern fencing’s

foil, épée, and sabre. The disparity revealed in this contrast underscores

their considerable dissimilarity. Spotlighting these differences I believe

can go a long way toward helping understand the place of Renaissance martial

arts study today.

There

is no question that when exposed to the authentic methods and techniques

of the longsword people are very often surprised at how unique its actions

are. Its distinct manner of use is then easily discerned in comparison

to what they know from modern fencing, regularly witness from choreographed

scenes in popular entertainment, or experience in familiar displays of

stunt fencing. Any sound attempt to address this topic must therefore

begin with one incontestable fact: modern

fencing includes no equivalent system of fighting to that of the longsword

--- a weapon that is arguably the foundational tool of Renaissance martial

arts. There

is no question that when exposed to the authentic methods and techniques

of the longsword people are very often surprised at how unique its actions

are. Its distinct manner of use is then easily discerned in comparison

to what they know from modern fencing, regularly witness from choreographed

scenes in popular entertainment, or experience in familiar displays of

stunt fencing. Any sound attempt to address this topic must therefore

begin with one incontestable fact: modern

fencing includes no equivalent system of fighting to that of the longsword

--- a weapon that is arguably the foundational tool of Renaissance martial

arts.

Setting

aside factors of associated exercise and drill, what can we note of the

major differences between the practice of the late Medieval and early

Renaissance longsword compared with that for the tools of modern fencing?

In the first instance we are referring to what is now known of the martial

practice of essentially German and Italian warswords of the 14th to 16th

centuries. In the second case we are referring to the post-Renaissance

style of Baroque foil, epee, and sabre dueling sports refined in the 19th

century and formalized in the early 20th. Each of these sword groups and

their individual manner of use developed under particular military and

civilian self-defense environments, with their own particular social and

cultural components. Without intending any value judgments, in one instance

we have a weapon of war that, in several forms, was intended for self-defense

in battle and judicial combat. On the other side we have versions of swords

designed strictly for unarmored fighting that are now pseudo-weapons devised

exclusively for a sport of gentlemanly mock-duel. Neither group

of swords was ever employed against the other historically (or competitively).

They are separated by centuries of change in military technology and self-defence

needs. Setting

aside factors of associated exercise and drill, what can we note of the

major differences between the practice of the late Medieval and early

Renaissance longsword compared with that for the tools of modern fencing?

In the first instance we are referring to what is now known of the martial

practice of essentially German and Italian warswords of the 14th to 16th

centuries. In the second case we are referring to the post-Renaissance

style of Baroque foil, epee, and sabre dueling sports refined in the 19th

century and formalized in the early 20th. Each of these sword groups and

their individual manner of use developed under particular military and

civilian self-defense environments, with their own particular social and

cultural components. Without intending any value judgments, in one instance

we have a weapon of war that, in several forms, was intended for self-defense

in battle and judicial combat. On the other side we have versions of swords

designed strictly for unarmored fighting that are now pseudo-weapons devised

exclusively for a sport of gentlemanly mock-duel. Neither group

of swords was ever employed against the other historically (or competitively).

They are separated by centuries of change in military technology and self-defence

needs.

To

best understand the technical and methodological differences between these

fencing styles some context is necessary. It is no difficulty to understand

that the military and social changes that occurred over the generations

influenced designs of swords and affected occasions for sword combat.

Longswords, by necessity, faced polearms, shields, two-weapon combinations,

daggers, hard and soft armors, in group and individual encounters.

A prerequisite of this time was the ability to both cut and thrust forcibly

as well as grapple effectively, whether armored or unarmored, mounted

or on foot. In the face of substantially different war technologies, by

the 18th and 19th centuries military swordplay deteriorated considerably

and atrophied into near vestigial forms from that of past ages. At the

same time the sword declined in its battlefield utility, fencing styles

became focused more on aristocratic duels of honors emphasizing the mere

drawing of blood over the delivery of lethal killing blows in instances

of general self-defense. To

best understand the technical and methodological differences between these

fencing styles some context is necessary. It is no difficulty to understand

that the military and social changes that occurred over the generations

influenced designs of swords and affected occasions for sword combat.

Longswords, by necessity, faced polearms, shields, two-weapon combinations,

daggers, hard and soft armors, in group and individual encounters.

A prerequisite of this time was the ability to both cut and thrust forcibly

as well as grapple effectively, whether armored or unarmored, mounted

or on foot. In the face of substantially different war technologies, by

the 18th and 19th centuries military swordplay deteriorated considerably

and atrophied into near vestigial forms from that of past ages. At the

same time the sword declined in its battlefield utility, fencing styles

became focused more on aristocratic duels of honors emphasizing the mere

drawing of blood over the delivery of lethal killing blows in instances

of general self-defense.

As

greatswords, two-handed swords, and bastard-swords, the long double-handed

European sword varied from wide parallel-edged blades suited to powerful

cleaving blows, to acutely tapering ones intended for thrusting at stronger

armors. Their design was never uniform but varied only within certain

limits and their blades came in several cross-sectional geometries that

might be flanged or squared. Their hilts might be of a simple cruciform

design with long handle or any manner of elaborately ringed bars and contracting

grip. (Some version of longswords were even single-edged with clipped

points) In their variety they were much like their single-hand cousins,

the common arming sword. But regardless of their form or geographic

region of use, over centuries longswords followed a closely similar method

of use (the singular styles of immense two-handed great-swords of the

16th century not being in consideration here). Study of the longsword

was historically accomplished by swordsmen working with “sharps,”

using wooden practice versions, and relying on special blunt training

blades. As

greatswords, two-handed swords, and bastard-swords, the long double-handed

European sword varied from wide parallel-edged blades suited to powerful

cleaving blows, to acutely tapering ones intended for thrusting at stronger

armors. Their design was never uniform but varied only within certain

limits and their blades came in several cross-sectional geometries that

might be flanged or squared. Their hilts might be of a simple cruciform

design with long handle or any manner of elaborately ringed bars and contracting

grip. (Some version of longswords were even single-edged with clipped

points) In their variety they were much like their single-hand cousins,

the common arming sword. But regardless of their form or geographic

region of use, over centuries longswords followed a closely similar method

of use (the singular styles of immense two-handed great-swords of the

16th century not being in consideration here). Study of the longsword

was historically accomplished by swordsmen working with “sharps,”

using wooden practice versions, and relying on special blunt training

blades.

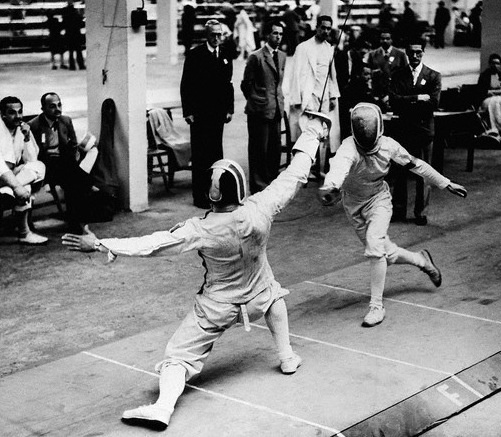

In

contrast, the three current tools of modern fencing (foil, epee, and saber)

have for more than a century existed almost exclusively as sporting versions

--- mock-weapons almost incapable of lethal injury. Their highly flexible

featherweight forms (two descended from the later rapier or smallsword

and the third from a type of light dueling broadsword or cutlass) are

far removed from their historical counterparts. They were intentionally

devised for scoring safe points in a mock duelling game and serve for

all aspects of practice. They were never real swords used for any actual

close-combat self-defense. Their system is based exclusively on a regulated

single-combat encounter against the same identical weapon. Their limited

style of play is restricted to formal actions that at times reward what

would otherwise be suicidal to attempt in life or death fights. Even if

given sharp points these tools would be difficult to be put into lethal

use under open conditions. It is these distinctions that then bring

us to the major ways they differ.

Ten Central Reasons

Here then are ten fundamental reasons I offer

for why longsword fencing differs so much form modern fencing:

1. Two-handed Actions: By its nature, using two-hands on

a weapon obviously permits (and encourages) more powerful blows that can

be instantly deadly. Using two hands on a longer weapon also teaches the

fencer almost instinctively to use greater body leverage. This in turn

cultivates finding different leverage points against an opposing two-handed

weapon than those occurring with a single-handed weapon (especially a

slender foyning---thrusting---sword). But beyond this, double-handed control

of a weapon affects the way in which it can be torqued around, and thus,

the range of symmetrical motions that are permissible. This further influences

the ideal form of stances, manners of stepping, and the diversity of fighting

actions. Far more so than with actions performed with one arm (or the

mere fingers of a single hand), the whole body and the full arm becomes

involved to nimbly wield the weapon symmetrically with proper strength.

Correspondingly, the fencer immediately learns to deal with the onslaught

of forceful cuts and thrusts deliverable with two-hands on any nearly

kind of weapon. Of course, even when training with two-hands on a longer

sword the fencer still learns to effectively use the weapon in one hand

when necessary. Permitting only one hand on a sword---any kind of sword---eliminates

a whole dimension of possible application, as well as the best way to

defend against such action.

1. Two-handed Actions: By its nature, using two-hands on

a weapon obviously permits (and encourages) more powerful blows that can

be instantly deadly. Using two hands on a longer weapon also teaches the

fencer almost instinctively to use greater body leverage. This in turn

cultivates finding different leverage points against an opposing two-handed

weapon than those occurring with a single-handed weapon (especially a

slender foyning---thrusting---sword). But beyond this, double-handed control

of a weapon affects the way in which it can be torqued around, and thus,

the range of symmetrical motions that are permissible. This further influences

the ideal form of stances, manners of stepping, and the diversity of fighting

actions. Far more so than with actions performed with one arm (or the

mere fingers of a single hand), the whole body and the full arm becomes

involved to nimbly wield the weapon symmetrically with proper strength.

Correspondingly, the fencer immediately learns to deal with the onslaught

of forceful cuts and thrusts deliverable with two-hands on any nearly

kind of weapon. Of course, even when training with two-hands on a longer

sword the fencer still learns to effectively use the weapon in one hand

when necessary. Permitting only one hand on a sword---any kind of sword---eliminates

a whole dimension of possible application, as well as the best way to

defend against such action.

2. Two-Edge Striking: Most straight two-handed sword blades were

double-edged. Though this may seem obvious, it is a crucial element in

fencing. The significance of this has been horrendously overlooked among

modern sword enthusiasts and arms historians. Two edges permit twice

as many cuts as a single edge. This goes far beyond mere chopping and

hacking. With a long double-hand sword, especially, many cuts are performed

with the back of the sword (the

“short” edge). It multiplies the strikes possible as well

as alters the way leverage and other actions can be employed. This

allows a more versatile combination of techniques to be rapidly delivered.

With the longsword either edge may be used symmetrically for any action. There are no similar two-edge actions in modern fencing. With the exception of minor actions by the short false edge on the back the sabre all

cuts are performed with the forward leading edge. There are no true

doube-edge strikes possible with it given its assymetrical manner of

gripping, while the foil and epee do not use any cuts in any form

whatsoever. This removes another whole dimension of

application. (There are also no “slicing actions” in modern

fencing whereby an edge is pressed forcibly against a target to produce

a slashing wound.)

3.

Use of the Second Hand: Another obvious element of fencing

with a longsword is that because two hands are used, either hand is employed

as needed. This means that as the primary-hand grips the weapon the second

hand may let go to thereby knock aside threats, strike blows with the

palm or fist, grip the opponent or seize his weapon. Aside from interfering

with their freedom of action or even disarming them, the whole arm may

be employed in this way to gain a leverage advantage. Such offensive and

defensive techniques are integral and intrinsic to Medieval and Renaissance

close combat in general. Made with quick and coordinated motions they

lead to a diverse and sophisticated repertoire of grappling and disarming

moves that make up a considerable component of overall martial prowess.

It is impossible to understand Renaissance fencing without skillful use

of the second hand in this way. (To do otherwise would be akin to attempting

to box with one hand against a boxer using two.) Modern fencing,

by contrast, does not permit any contact of the second hand with the weapon

or the body of either combatant.

The reasoning for this has nothing to do with combat effective swordsmanship.

It instead reflects the later etiquette that grabbing and slapping at

weapons, seizing one another’s garments, and striking with the empty

hand was unseemly for a gentleman’s duel or “civilized”

sport. Though lost to later fencing styles and long misunderstood, actions

with the free-hand are especially germane to the longsword. 3.

Use of the Second Hand: Another obvious element of fencing

with a longsword is that because two hands are used, either hand is employed

as needed. This means that as the primary-hand grips the weapon the second

hand may let go to thereby knock aside threats, strike blows with the

palm or fist, grip the opponent or seize his weapon. Aside from interfering

with their freedom of action or even disarming them, the whole arm may

be employed in this way to gain a leverage advantage. Such offensive and

defensive techniques are integral and intrinsic to Medieval and Renaissance

close combat in general. Made with quick and coordinated motions they

lead to a diverse and sophisticated repertoire of grappling and disarming

moves that make up a considerable component of overall martial prowess.

It is impossible to understand Renaissance fencing without skillful use

of the second hand in this way. (To do otherwise would be akin to attempting

to box with one hand against a boxer using two.) Modern fencing,

by contrast, does not permit any contact of the second hand with the weapon

or the body of either combatant.

The reasoning for this has nothing to do with combat effective swordsmanship.

It instead reflects the later etiquette that grabbing and slapping at

weapons, seizing one another’s garments, and striking with the empty

hand was unseemly for a gentleman’s duel or “civilized”

sport. Though lost to later fencing styles and long misunderstood, actions

with the free-hand are especially germane to the longsword.

4. Half-Swording: As a weapon, the longsword was never

just held by the handle (as is so ubiquitous in modern depictions of historical

sword combat within popular media and games.) A

common technique with most all Medieval and Renaissance swords was that

of “half-swording” --- the grasping of almost any portion

of the blade with one or even both hands. Whether for a wide or a tapering

blade, a considerable portion of longsword technique in both armored and

unarmored fighting consisted of this. Blades were gripped in such a way

as to prevent the palm or fingers being sliced open. In this manner

the sword could be instantly shortened for quick forceful thrusts, ward

with greater coverage, and held for increased leverage when close in.

Managed in such a way the longsword could be easily manipulated as if

it were a short staff to press, hit, and trap with either end as well

as with the point. It could also be wielded as if it were a spear, a warhammer,

or a polaxe, striking (or defending) with the pommel or cross. Quickly

transitioning back and forth between such actions provided for a powerful

and fluid form of fencing that permitted a dynamic use of leverage. There

is no equivalent to half-swording in modern fencing, wherein for reasons

of etiquette and sportsmanship participants are forbidden in anyway from

touching either their own blade or that of their opponent.

4. Half-Swording: As a weapon, the longsword was never

just held by the handle (as is so ubiquitous in modern depictions of historical

sword combat within popular media and games.) A

common technique with most all Medieval and Renaissance swords was that

of “half-swording” --- the grasping of almost any portion

of the blade with one or even both hands. Whether for a wide or a tapering

blade, a considerable portion of longsword technique in both armored and

unarmored fighting consisted of this. Blades were gripped in such a way

as to prevent the palm or fingers being sliced open. In this manner

the sword could be instantly shortened for quick forceful thrusts, ward

with greater coverage, and held for increased leverage when close in.

Managed in such a way the longsword could be easily manipulated as if

it were a short staff to press, hit, and trap with either end as well

as with the point. It could also be wielded as if it were a spear, a warhammer,

or a polaxe, striking (or defending) with the pommel or cross. Quickly

transitioning back and forth between such actions provided for a powerful

and fluid form of fencing that permitted a dynamic use of leverage. There

is no equivalent to half-swording in modern fencing, wherein for reasons

of etiquette and sportsmanship participants are forbidden in anyway from

touching either their own blade or that of their opponent.

5. Displacing of Strikes: The historical source teachings on the

longsword are unanimous that defensive actions are best accomplished by

offensive actions. They recommend

the optimal defense as bring a single-time action---a counter-strike that

displaces (or breaks) the oncoming cut or thrust. What is most difficult

for modern fencers and sword enthusiasts to grasp is the concept of defense

found throughout Renaissance fighting literature: simultaneously delivering

a strike while in the same motion closing-in to stifle an attack by encountering

the opponent’s weapon near its hilt using your blade near its hilt.

This action takes into account the force of the strikes that must be opposed

as well as the understanding that closing against an attacker is frequently

an ideal option. Where counter-striking a blow is not always possible,

warding off or setting aside a cut (by receiving it on the flat of the

blade, not the edge) is then proscribed. However, passively catching oncoming

strikes with a rigid block (common practice in modern fencing) was never

advised.  This

is the opposite of the simpler “parry-riposte” theory of swordplay that

dominates so many forms of fencing now. Statically taking a blow edge

on edge, as became standard operating procedure throughout the

post-Renaissance broadsword and cutlass play of the 18th and 19th

centuries, was simply not taught. Modern fencing, by comparison, relies

almost solely on this “double-time” defense with a separate intentional

parrying action (derived from the Baroque smallsword, and even deemed a

progressive idea). With the modern fencing sabre, whose blade is a mere

thin vestigial rod, any portion of the edge may even suffice for

blocking cuts. Counter-cuts that displace, whether by meeting hilt to

hilt or by striking to the flat of the opponent’s blade, are entirely

unknown except for those minor ones that can naturally occur with

body motion. The profound change in dynamic that occurs between fencing

concerned not with static blocking but with counter-striking and

closing in to prevent the opponent’s freedom of action cannot be

emphasized enough. This

is the opposite of the simpler “parry-riposte” theory of swordplay that

dominates so many forms of fencing now. Statically taking a blow edge

on edge, as became standard operating procedure throughout the

post-Renaissance broadsword and cutlass play of the 18th and 19th

centuries, was simply not taught. Modern fencing, by comparison, relies

almost solely on this “double-time” defense with a separate intentional

parrying action (derived from the Baroque smallsword, and even deemed a

progressive idea). With the modern fencing sabre, whose blade is a mere

thin vestigial rod, any portion of the edge may even suffice for

blocking cuts. Counter-cuts that displace, whether by meeting hilt to

hilt or by striking to the flat of the opponent’s blade, are entirely

unknown except for those minor ones that can naturally occur with

body motion. The profound change in dynamic that occurs between fencing

concerned not with static blocking but with counter-striking and

closing in to prevent the opponent’s freedom of action cannot be

emphasized enough.

6. Binding and Winding: The willingness to aggressively enter in

to bind and wind against the opponent’s weapon was a chief characteristic

of close-combat in the Medieval and Renaissance eras. The longsword

did not utilize the deliberately restrained parry and riposte so common

in modern depictions of swordfights and illusory swordplay found in popular

entertainment. Instead, the longsword’s length and inertia were

utilized to actively intercept against and around the opponent’s

wards, striking to their openings or forcing their defense, the whole

time gaging their pressure and controlling leverage blade on blade. All

the while, every opportunity was taken to exploit the entire inventory

of actions available to a swordsman---forcibly delivering cuts, thrusts,

and slices with either edge as well as freely entering in close to use

the hilt, grip the blade, and use the second hand. The physical attributes

of the longsword and the context of its fighting was not focused on simply

gaining range and timing while feinting back and forth in rapid linear

attack and parry exchanges without body-to-body contact, as conducted

in fencing now. Rather, binding and winding requires intentionally

seeking close contact with the opponent’s weapon and/or body.

7.

Full-Body Action: Full-body action in striking at targets and affecting

balance is crucial to all aspects of a fighting art, whether armed or

unarmed. In practicing the longsword it is assumed that blows are to be

delivered in a lethal manner. Although, it is recognized that due to the

quality of strikes, the location of wounds, and differences in physiology

and temperate among fighters, not all blows are always immediately debilitating

or incapacitating. It is also understood that though blows are to be performed

with full speed and force (practiced as if for lethal intent), for reasons

of practical safety in training this is not possible at all times.

Nonetheless, there is constant awareness in the longsword fencer of the

opponent’s entire anatomy as a valid target and cognizance of what

techniques to what locations will produce lethal results. No part of the

body is ignored as an invalid target or one that a blow can be received

upon without serious consequence. Additionally, an inherent appreciation

is developed for how the head-to-toe workings of key joints and muscles

relate to leveraging the opponent’s balance at all points of contact.

A longsword fencer must always act with purposeful consideration for the

mutual use of forceful body contact to gain leverage. To strike with necessary

force, the longsword fencer employs passing, traversing, turning, leading

with either leg, forceful arm and leg motions, and maintaining a lower

stance. The longsword fencer cannot allow his leg to be swept out from

under him, his foot or thigh to be stomped on, his knee, groin, or stomach

to be kicked, his face struck by a hilt or hand, or his arm and weapon

to be grabbed. None of these elements are a concern whatsoever in fencing

with the foil, epee, or sabre, where any hit is as good as any other and

no awareness of body-to-body leverage (or body to weapon leverage) is

cultivated. In modern fencing blade-on-blade play is the exclusive focus

of all action. 7.

Full-Body Action: Full-body action in striking at targets and affecting

balance is crucial to all aspects of a fighting art, whether armed or

unarmed. In practicing the longsword it is assumed that blows are to be

delivered in a lethal manner. Although, it is recognized that due to the

quality of strikes, the location of wounds, and differences in physiology

and temperate among fighters, not all blows are always immediately debilitating

or incapacitating. It is also understood that though blows are to be performed

with full speed and force (practiced as if for lethal intent), for reasons

of practical safety in training this is not possible at all times.

Nonetheless, there is constant awareness in the longsword fencer of the

opponent’s entire anatomy as a valid target and cognizance of what

techniques to what locations will produce lethal results. No part of the

body is ignored as an invalid target or one that a blow can be received

upon without serious consequence. Additionally, an inherent appreciation

is developed for how the head-to-toe workings of key joints and muscles

relate to leveraging the opponent’s balance at all points of contact.

A longsword fencer must always act with purposeful consideration for the

mutual use of forceful body contact to gain leverage. To strike with necessary

force, the longsword fencer employs passing, traversing, turning, leading

with either leg, forceful arm and leg motions, and maintaining a lower

stance. The longsword fencer cannot allow his leg to be swept out from

under him, his foot or thigh to be stomped on, his knee, groin, or stomach

to be kicked, his face struck by a hilt or hand, or his arm and weapon

to be grabbed. None of these elements are a concern whatsoever in fencing

with the foil, epee, or sabre, where any hit is as good as any other and

no awareness of body-to-body leverage (or body to weapon leverage) is

cultivated. In modern fencing blade-on-blade play is the exclusive focus

of all action.

8. Grappling: That grappling (wrestling or unarmed moves) was long

an integral component of fencing skills is indisputable. Body contact

involving leveraging with both hands and even the weapon itself is an

important aspect of armed combat that cannot be separated from the reality

of Medieval and Renaissance swordplay. At the closest range disarms, throws,

take downs, kicks, hand blows, and seizing and trapping, are employed

in conjunction with whatever sword or hand weapon a fighter has. These

actions were removed from later fencing only as aristocratic gentlemen

came to consider grabbing at one another, tearing at clothing, or franticly

clutching at each other’s weapons to be uncouth and ill-suited to

a refined activity of mannered deportment. To “hit and not be hit”

does not mean to never touch the other person’s body or weapon in

the process. Holding and seizing, pushing and pulling, leveraging with

arm, knee, leg, and foot are neither primitive nor crude. To employ them

safely and effectively demands considerable fencing skills on the part

of the swordsman. Excluding them is not an “improvement” of

fencing skill but a narrowing de-evolution. Indeed, fencing is at its

most expert when these things augment and extend the utility of a sword.

But modern fencing does not involve coming to the ground at any

time. The fencers at no time ever learn to fall or to make someone else

fall.

8. Grappling: That grappling (wrestling or unarmed moves) was long

an integral component of fencing skills is indisputable. Body contact

involving leveraging with both hands and even the weapon itself is an

important aspect of armed combat that cannot be separated from the reality

of Medieval and Renaissance swordplay. At the closest range disarms, throws,

take downs, kicks, hand blows, and seizing and trapping, are employed

in conjunction with whatever sword or hand weapon a fighter has. These

actions were removed from later fencing only as aristocratic gentlemen

came to consider grabbing at one another, tearing at clothing, or franticly

clutching at each other’s weapons to be uncouth and ill-suited to

a refined activity of mannered deportment. To “hit and not be hit”

does not mean to never touch the other person’s body or weapon in

the process. Holding and seizing, pushing and pulling, leveraging with

arm, knee, leg, and foot are neither primitive nor crude. To employ them

safely and effectively demands considerable fencing skills on the part

of the swordsman. Excluding them is not an “improvement” of

fencing skill but a narrowing de-evolution. Indeed, fencing is at its

most expert when these things augment and extend the utility of a sword.

But modern fencing does not involve coming to the ground at any

time. The fencers at no time ever learn to fall or to make someone else

fall.

9. Hilt and Gripping: The composition of the hilt on a longsword

(typically a simple cross-guard or cruciform shape) is a direct factor

of how the weapon is used. The longsword’s hilt was employed as

much for offensive as for defensive actions. Its function is more sophisticated

than has been commonly presented in choreographed fight scenes and stunt

fighting performances. The longsword’s hilt is in no way inferior

or less developed than the compound bars and cups attached to later swords.

Additionally, such hilts sometimes had side rings and sloped bars, which

facilitated in actively catching and guarding against other blades and

hilts. Further, there are also several versatile manners of gripping a

longsword that permit different actions or allow various techniques. These

may involve the placement of the thumb on the cross bar or the flat of

the blade, wrapping the index finger around the cross, grasping the pommel

in the palm, shifting the grip toward the center of the handle, shifting

the weapon to one hand, or holding the weapon by the blade itself. The

blade may even have flanges (small protruding spikes) above its cross

that assist in binding, winding, and trapping. None of these central

elements is known or of any significance with the style used for modern

fencing.

9. Hilt and Gripping: The composition of the hilt on a longsword

(typically a simple cross-guard or cruciform shape) is a direct factor

of how the weapon is used. The longsword’s hilt was employed as

much for offensive as for defensive actions. Its function is more sophisticated

than has been commonly presented in choreographed fight scenes and stunt

fighting performances. The longsword’s hilt is in no way inferior

or less developed than the compound bars and cups attached to later swords.

Additionally, such hilts sometimes had side rings and sloped bars, which

facilitated in actively catching and guarding against other blades and

hilts. Further, there are also several versatile manners of gripping a

longsword that permit different actions or allow various techniques. These

may involve the placement of the thumb on the cross bar or the flat of

the blade, wrapping the index finger around the cross, grasping the pommel

in the palm, shifting the grip toward the center of the handle, shifting

the weapon to one hand, or holding the weapon by the blade itself. The

blade may even have flanges (small protruding spikes) above its cross

that assist in binding, winding, and trapping. None of these central

elements is known or of any significance with the style used for modern

fencing.

10. Weight of the Weapon: Longswords were never usually more than

3 or 4 pounds. This was a factor of the need at the time to “use

force” and “strike strongly” in close combat. The longsword’s

size and mass would seem the most obvious area of difference between it

and the tools of modern fencing. Yet, this is easily the least noteworthy

consideration. Whether for the tapering thinner form of blade (i.e., a

spadone or espée

bastardo) or the wider parallel-edged design (a warsword or espée

du guerre), the longsword was required to face other diverse weapons

and armors, and even multiple opponents. It was expected to find use under

any conditions and on any ground, not merely encounter an identical copy

of itself in unarmored single combat. The weapon’s weight therefore

gives it a distinctly different sense of maneuverability and force, compelling

transitions from warding to cut and thrust as well as crossing to close

in. This is in turn obliges different stances than the linear L-shaped

one of modern fencing.

10. Weight of the Weapon: Longswords were never usually more than

3 or 4 pounds. This was a factor of the need at the time to “use

force” and “strike strongly” in close combat. The longsword’s

size and mass would seem the most obvious area of difference between it

and the tools of modern fencing. Yet, this is easily the least noteworthy

consideration. Whether for the tapering thinner form of blade (i.e., a

spadone or espée

bastardo) or the wider parallel-edged design (a warsword or espée

du guerre), the longsword was required to face other diverse weapons

and armors, and even multiple opponents. It was expected to find use under

any conditions and on any ground, not merely encounter an identical copy

of itself in unarmored single combat. The weapon’s weight therefore

gives it a distinctly different sense of maneuverability and force, compelling

transitions from warding to cut and thrust as well as crossing to close

in. This is in turn obliges different stances than the linear L-shaped

one of modern fencing.  Contrary

to many modern misrepresentations, longsword footwork hardly employed

the same identical stepping and lunging of the modern style. As an athletic

craft of disciplined violence, the deadly force required in earnest encounters

with such robust weapons demanded training to strike with speed, accuracy,

and deception. All actions are optimized for incapacitating and debilitating

impacts. At no time does a longsword fencer contemplate executing a suicidal

attack because they will score a hit a millisecond sooner than their opponent.

Rather, if at any time an adversary is considered still capable of continued

lethal resistance, then the fight has hardly ended. The longsword fencer

does not drop his guard because he knows he has made an effective hit

under a set of rules. It is always assumed a mortally wounded opponent

is still entirely capable of striking back. In modern fencing, however,

once having made a valid hit on the opponent, with a flexible weapon weighing

mere ounces, no effort is made to immediately avoid being struck afterward

by an otherwise lethal blow. Such blows are simply ignored. Contrary

to many modern misrepresentations, longsword footwork hardly employed

the same identical stepping and lunging of the modern style. As an athletic

craft of disciplined violence, the deadly force required in earnest encounters

with such robust weapons demanded training to strike with speed, accuracy,

and deception. All actions are optimized for incapacitating and debilitating

impacts. At no time does a longsword fencer contemplate executing a suicidal

attack because they will score a hit a millisecond sooner than their opponent.

Rather, if at any time an adversary is considered still capable of continued

lethal resistance, then the fight has hardly ended. The longsword fencer

does not drop his guard because he knows he has made an effective hit

under a set of rules. It is always assumed a mortally wounded opponent

is still entirely capable of striking back. In modern fencing, however,

once having made a valid hit on the opponent, with a flexible weapon weighing

mere ounces, no effort is made to immediately avoid being struck afterward

by an otherwise lethal blow. Such blows are simply ignored.

Contrast in Consideration

The

ten points described here combine to reveal something that may serve to

summarize the fundamental underlying difference at work: The nature of

longsword fencing is about the practice of fighting

skills---the study of a martial art. This is self-apparent but

it bears clarification. As in the study of other Medieval and Renaissance

weaponry, bouting (or free-play) with the longsword is conducted not as

an end in itself but for purposes of developing skill in the craft. As

opposed to skill being directed toward a game of scoring points in a mock

duel, a large repertoire of the actions in fencing with the longsword

consists of techniques which are actually too dangerous or too brutal

to safely use in mock combat, but nonetheless must be trained in and prepared

for. The

ten points described here combine to reveal something that may serve to

summarize the fundamental underlying difference at work: The nature of

longsword fencing is about the practice of fighting

skills---the study of a martial art. This is self-apparent but

it bears clarification. As in the study of other Medieval and Renaissance

weaponry, bouting (or free-play) with the longsword is conducted not as

an end in itself but for purposes of developing skill in the craft. As

opposed to skill being directed toward a game of scoring points in a mock

duel, a large repertoire of the actions in fencing with the longsword

consists of techniques which are actually too dangerous or too brutal

to safely use in mock combat, but nonetheless must be trained in and prepared

for.

The

significance of this distinction, in terms of both the mindset and application

of fighting discipline, cannot be understated. It directly affects how

a student of the subject approaches its study today. It also shatters

the assertion that post-Baroque fencing can serve as a basis for modern

study of the longsword. Just as a you would not want to try to fence

with the method of the longsword using the weapons of modern fencing,

neither would you want to try to wield a longsword with the style of the

foil, epee, or saber (though, many have tried and some shamefully still

do).

The

comparison here, then, essentially comes down to comparing a respected

sport with a recovered martial art --- that is, a tactical and athletic

competitive game on one hand with a close-combat system for a weapon of

war and single-combat on the other. As ideally pursued today, the method

employed with the longsword is taken from the direct historical source

teachings of Masters of Defense from an era for which the weapon was readily

employed in all manner of brutal and savage close-combat. The fencing

style of the modern sport, by contrast, largely descends from those contrived

for gentlemanly duels, developed in an age unmolested by the challenges

of diverse arms and armors on and off the battlefield. This was then modified

into an artificial game. Whereas the longsword is currently undergoing

its own reconstruction process of interpretation and revival, modern fencing

has already undergone a considerable process of “de-martialization”

(i.e., ritualization, civilianization, and sportification). The

comparison here, then, essentially comes down to comparing a respected

sport with a recovered martial art --- that is, a tactical and athletic

competitive game on one hand with a close-combat system for a weapon of

war and single-combat on the other. As ideally pursued today, the method

employed with the longsword is taken from the direct historical source

teachings of Masters of Defense from an era for which the weapon was readily

employed in all manner of brutal and savage close-combat. The fencing

style of the modern sport, by contrast, largely descends from those contrived

for gentlemanly duels, developed in an age unmolested by the challenges

of diverse arms and armors on and off the battlefield. This was then modified

into an artificial game. Whereas the longsword is currently undergoing

its own reconstruction process of interpretation and revival, modern fencing

has already undergone a considerable process of “de-martialization”

(i.e., ritualization, civilianization, and sportification).

These

significant differences help explain why the longsword has in modern times

been poorly considered and almost wholly misunderstood, and thus also

why its lost art remained for so long unrealized and un-recovered by modern

era fencing masters and sword enthusiasts. With no one who retained

its teachings, and few who were attempting to credibly pursue it as a

true martial art along in appropriate manner, it is no wonder its distinction

from modern sporting styles has been so little understood. These

significant differences help explain why the longsword has in modern times

been poorly considered and almost wholly misunderstood, and thus also

why its lost art remained for so long unrealized and un-recovered by modern

era fencing masters and sword enthusiasts. With no one who retained

its teachings, and few who were attempting to credibly pursue it as a

true martial art along in appropriate manner, it is no wonder its distinction

from modern sporting styles has been so little understood.

While

the fencing of foil, epee, and sabre have been well-established as casual

combat sports for more than a century now, to be legitimately studied

again today the rich but entirely forgotten tradition of the European

longsword must be approached from the perspective of its historical practice---as

a true martial art, not a recreational game. This fact is all the

more obvious when we fully realize the incontestable differences between

the two. (This certainty also renders more clearly the reasons why modern

fencers have long failed to reproduce the lost teachings of Renaissance

combatives.) While

the fencing of foil, epee, and sabre have been well-established as casual

combat sports for more than a century now, to be legitimately studied

again today the rich but entirely forgotten tradition of the European

longsword must be approached from the perspective of its historical practice---as

a true martial art, not a recreational game. This fact is all the

more obvious when we fully realize the incontestable differences between

the two. (This certainty also renders more clearly the reasons why modern

fencers have long failed to reproduce the lost teachings of Renaissance

combatives.)

Modern

styles of fencing originate from those developed during the

Enlightenment and the Age of Reason, in which defending aristocratic

honor and the punctilios of gentlemanly etiquette were the larger concern.

The longsword, by contrast, is a product of a Medieval and Renaissance

warrior ethos. They each are the product of two very different fencing

cultures. This is reflected in the significant difference by which both

are practiced.

While

modern fencing’s conceptualized gentlemanly duel is a great competitive

sport and athletic game with its own respectable lineage, it

is not a martial art. It is a version of mock-dueling far removed

from its far more sophisticated Renaissance ancestors. While the specialization

of fencing actions down into just a handful of possibilities necessary

to score a point with flexible practice-weapons in a safe sport can seem

like an evolutionary refinement, it is rather an attempt to control the

chaos of close combat by minimizing it into a game that can be prescribed

rules and boundaries. To elide in this way makes sense when reducing techniques

to the specialized needs of a martial sport or the narrow context of a

ritualized combat. While

modern fencing’s conceptualized gentlemanly duel is a great competitive

sport and athletic game with its own respectable lineage, it

is not a martial art. It is a version of mock-dueling far removed

from its far more sophisticated Renaissance ancestors. While the specialization

of fencing actions down into just a handful of possibilities necessary

to score a point with flexible practice-weapons in a safe sport can seem

like an evolutionary refinement, it is rather an attempt to control the

chaos of close combat by minimizing it into a game that can be prescribed

rules and boundaries. To elide in this way makes sense when reducing techniques

to the specialized needs of a martial sport or the narrow context of a

ritualized combat.

But

the commensurate loss of self-defense knowledge that then takes place

is the very antithesis of the martial skill required in a broader combat

system. It is only because the

craft of the longsword has only recently been reconstructed with any accuracy

(entirely outside of the community of modern fencing, we must note) that

these differences of form (and bio-mechanics) can now be clarified.

Such then is the difference between the sport of modern fencing and the

historical martial art of the longsword. Understanding this context will

permit practitioners of either craft to better appreciate the place of

the other in the modern world.

See

also:

The

Centrality of the Longsword in Renaissance Martial Arts Study

January

2009

|