What

Makes an Effective Sword Cut?

What

Makes an Effective Sword Cut?

By J. Clements

What makes an effective sword cut? If by this we mean one that

causes significant damage to the target there are many factors involved,

but they are neither secret nor mysterious. Obviously, the force

of a cut is a factor of accelerating the mass of the weapon to impact.

Naturally, a stronger strike produces a better result.

Compared to a cut the effectiveness of a sword thrust is determined

by a simple matter of how resistant the target is at the point of

impact, how large a hole the blade can produce, how deep the wound

penetrates, and whether a vital region is struck. A cut by contrast

has many more variables affecting it.

Physical strength and size of a swordsman as well as the mass of

the weapon itself all act to produce the needed impact velocity

of a cut. Maximizing velocity in a cut is, in effect, only about

movement through space in a given interval of time. You can't increase

the mass (body weight) behind your blow or the mass of your weapon

either; you can only maximize how much of it you apply toward creating

velocity with your weapon. This is why cutting from the wrist is

not nearly as powerful as cutting from the shoulder, and why striking

by using one arm is not as strong as striking with two (imagine

using a baseball bat with one hand or swinging from the wrist alone

and you can easily understand why).

The physical aspects of cutting is itself a matter of efficient

kinetics. The application of the ideal body mechanics necessary

to cut well at any one instant, though quantifiable, is an art.

It's a matter of the elements of footwork, coordination, gripping

method, arm motion, aim, focus, and follow through --all of which

require practice to perform proficiently. But, all these elements

do is aid in accelerating mass in order to concentrate force (which

is a reason why you can't cut strongly yet slowly).

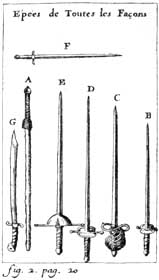

The

smaller the surface area the inertia of a cut is concentrated upon

the greater the impact effect will be. The sword's edge bevel and

cross-sectional shape both act to optimize this concentration of

force by reducing drag. Hence, this is why you have to aim your

blow to optimally align the edge. The wider and thinner a blade

is, the better it will naturally cut (this is why for instance,

a meat cleaver cuts so much better than a narrow and thick rapier).

The typical edge grind found on cutting blades of Medieval and Renaissance

times was slightly convex that continued directly into the cutting

sharpness. There was very seldom a secondary grind as found on many

modern knives.

The

smaller the surface area the inertia of a cut is concentrated upon

the greater the impact effect will be. The sword's edge bevel and

cross-sectional shape both act to optimize this concentration of

force by reducing drag. Hence, this is why you have to aim your

blow to optimally align the edge. The wider and thinner a blade

is, the better it will naturally cut (this is why for instance,

a meat cleaver cuts so much better than a narrow and thick rapier).

The typical edge grind found on cutting blades of Medieval and Renaissance

times was slightly convex that continued directly into the cutting

sharpness. There was very seldom a secondary grind as found on many

modern knives.

The resultant affect of a sword cut will be determined by the resistance

of the target material (such as whether it hits armor, cloth, flesh,

or bone, etc.) and the target's relative motion (whether it is moving

toward, away from, or at a tangent to the angulation of the edge

at the moment of impact).

While it should be no surprise that a sharp sword cuts better than

a dull one, less well understood is how the relationship between

a blade's mass distribution to cross-section is a matter of its

impact inertia and impact friction. Wide blades have more mass and

have a low cross-sectional profile that produces less friction upon

cutting impact. Wider blades are also stiffer by virtue of their

surface area. Whereas thicker but narrower blades are also stiff,

but with their high profiles produce much more friction when cutting

-although are more powerful on penetrating stabs. Swordsmith Paul

Champagne explains, "Different sword types of different historical

periods used different bevel and edge-geometries according to what

they are intended to do, just as the blade shape changes between

a cutting blade and a thrusting one." He adds, "Think

of a sword edge made for cutting as a shape moving through water,

the one with least resistance will be best."

Cutting

damage can be increased by the subsequent application of edge pressure

after the initial moment of contact --i.e., drawing and slicing

(but this action is independent of the initial impact). A

sword blade will also tend to flex somewhat upon strong impact and

this too minutely increases the drag and distorts the edge alignment.

Hitting in such a way to transmit the most force in a blow using

the ideal portion of the blade is a great theory. However, in swordsmanship

the most important thing was training to know where and when to

hit as much as "how." Besides, depending on the range

of the target at the instant of contact a sword edge could impact

with a different portion of its length than optimally intended.

Cutting

damage can be increased by the subsequent application of edge pressure

after the initial moment of contact --i.e., drawing and slicing

(but this action is independent of the initial impact). A

sword blade will also tend to flex somewhat upon strong impact and

this too minutely increases the drag and distorts the edge alignment.

Hitting in such a way to transmit the most force in a blow using

the ideal portion of the blade is a great theory. However, in swordsmanship

the most important thing was training to know where and when to

hit as much as "how." Besides, depending on the range

of the target at the instant of contact a sword edge could impact

with a different portion of its length than optimally intended.

A strong sword cut is also not made by just 'throwing forward'

the point or by whipping the weapon around in a big arc so that

the tip connects against the target, but rather it is made by using

the whole body to place maximum impact on the target with a good

portion of the edge. A laceration can of course be made by striking

on the human body with almost any object (e.g., a car antenna or

even a spoon) provided you have enough velocity behind it --it won't

sever tissue or deeply shear but it will tear and scratch).

Additionally, against the human body swords do not "stick"

nor do muscles "clamp down" or contract tightly upon being

cut. A blade quickly chopping or cleaving through flesh moves too

fast for this sort of thing. We have enough experience from those

in the Third World who regularly slaughter large animals with swords

to know this. Nor does the significant volume of documented accounts

of historical sword combats support such a myth either. Flesh is

very elastic and largely made up of water and while there is afterwards

a shock reaction that helps prevent fluid loss, this would not prevent

the forceful edge blow of a sharp bladed sword from being withdrawn.

As the swordsmasn and sword maker John Latham wrote in 1863, the mass a swordsman can move with greatest velocity is that with which he will produce the greatest effect with. But a light and quick sword is not necessarily the one he can move the fastest. While a light blade can impact with greater speed, a fighter can only move it so fast. The force of a cut is (primarily) a combination of speed and mass. But too heavy a blade moves slowly and is therefore weak, while too light a blade drags through the air and lacks impact weight. The solution is a cutting sword well-balanced between its center of gravity and its center of percussion.

To summarize, a powerful cut results from the elements of a well-executed

motion (the point moving in a circular arc, the hilt moving forward)

combined with coordinated footwork, body motion, speed, strength,

as well as edge placement, grip, focus, and follow-through--not

just from brute physical force or merely a super sharp edge. These

various factors may be among the very reasons why there was such

a thing called "swordsmanship," but not "axe-manship"

or "mace-manship", ect. Cutting effectively with an edged

weapon is, after all, not identical to hitting with say, a stick

or club.

The

varied elements of an effective sword cut are why so many different

blade shapes, cross-sections, and edge bevels were tried out by

swordmakers throughout history. All of this is also why two people

can test-cut with the exact same weapon on the very same target

material and achieve very different results--with one bashing and

knocking it and the other cleaving into or cleanly shearing though

it. Cutting well takes practice. It takes skill. It also takes a

good resilient and sharp blade for best results. Other than this

there is nothing else to it. No need for mysticism. No need for

obfuscations. No need for myth and hype.

The

varied elements of an effective sword cut are why so many different

blade shapes, cross-sections, and edge bevels were tried out by

swordmakers throughout history. All of this is also why two people

can test-cut with the exact same weapon on the very same target

material and achieve very different results--with one bashing and

knocking it and the other cleaving into or cleanly shearing though

it. Cutting well takes practice. It takes skill. It also takes a

good resilient and sharp blade for best results. Other than this

there is nothing else to it. No need for mysticism. No need for

obfuscations. No need for myth and hype.

Some modern reenactors, lacking experience in handling actual antique

weapons or cutting extensively with accurate reproductions, have

asserted that effective cuts always require a pulling or "drawing"

action commensurate with the blow. While with a straight blade such

an element is an inherent part of any cut (just as is focus, edge

placement, grip, velocity, force, and proper coordinated body motion

to follow through), it is unmistakably not a factor in either penetrating

armor or delivering traumatic concussion to tissues beneath armor.

The sharper the edge, the stronger or faster the blow, and the more

precise the angulation of the impact all make a difference in the

effectiveness of a sword cut. However, there can be no question

that powerful and effective cuts using straight blades are easily

performed without any appreciative drawing or slicing action. If

this were not so we might strike forcibly against a person with

a blunt sword or simple stick and expect not to cause injury. Yet,

devastatingly hard blows can obviously be made that even cleave

through unprotected flesh and bone. Impact forces cause a sword

to change its motion or yield to the blow, and the easier a sword

does this, the lighter the blow will be. This is the fundamental

reason that a very light sword cannot deliver the same power in

a blow as a heavier sword, which has more resistance to change in

motion. This is why skill is integral to cutting well.

Of course, a really good sword even if used with mediocre technique

can often still produce an effective cut, just as an expert swordsman

can at times cut well with even a poor quality weapon. Different

swords were designed to meet different situations, thus they did

not all exist to solve the same problem or cut the same exact things

and hence, were often used in somewhat different ways.

But regardless, all swords are cool.

See

also: Sword

Impacts and Motions